Ten Years of GWOT, the Failure of Democratization, and the Fallacy of "Ungoverned Spaces"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NPR Mideast Coverage April - June 2012

NPR Mideast Coverage April - June 2012 This report covers NPR's reporting on events and trends related to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians during the second quarter of 2012. The report begins with an assessment of the 37 stories and interviews, covered by this review, that aired from April through June on radio shows produced by NPR. The 37 radio items is just one more than the lowest number for any quarter (in July-September 2008) during the past ten years. Over that period, NPR programs have carried an average of nearly 100 items per quarter related to Israel, the Palestinians, or both. I also reviewed 20 news stories, blogs and other items carried exclusively on NPR's website. All of the radio and website-only items covered by this review are shown on the "Israel-Palestinian coverage" page of the website. The opinions expressed in this report are mine alone. Accuracy I carefully reviewed all items for factual accuracy, with special attention to the radio stories, interviews and website postings produced by NPR staffers. NPR's coverage of the region continues to be remarkably accurate for a news organization with very tight deadlines. NPR has posted no corrections on its website for stories that originated during the April-June quarter; two corrections were posted in April concerning items dealt with in my report for the January-March quarter. I found no outright inaccuracies during the period, but I will point out two instances of misleading use of language. Freelance correspondent Sheera Frenkel reported for All Things Considered on May 8 about the status of a hunger strike among Palestinian prisoners. -

A Structural Analysis of Personal Experience Narratives, the Federal Writers‘ Project to Storycorps

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE: A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL EXPERIENCE NARRATIVES, THE FEDERAL WRITERS‘ PROJECT TO STORYCORPS by Megan M. Dickson B.A. May 2007, Utah State University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 16, 2010 Thesis directed by John Michael Vlach Professor of American Studies and of Anthropology © Copyright 2010 by Megan Marie Dickson All rights reserved ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to the experiences we each have and share every day— in the park, over the phone, and sometimes even to a government employee (circa 1937), or with a loved one in a cozy StoryCorps sound booth in New York City. To my husband— Perry Dickson—without you, your love and strength, your championing and cheerleading this story would never have been possible. To my parents—Mona and Ken Farnsworth, and Robin Dickson—thank you for your unending love, support, encouragement, and belief. To my son Parker, whose story has only just begun, your vigor and verve for life already bring constant adventure and joy beyond measure. iii Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge and thank the faculty and staff of the American Studies department at The George Washington University. A special thanks to Maureen Kentoff—the most fabulous muse in American Studies Executive Assistant history for helping to navigate the sometime frightful waters of university protocol, and sharing ways to succeed as a non-traditional student; John Michael Vlach—my faithful advisor; Melanie McAlister—Director of Graduate Studies who administered my comprehensive examination; Phyllis Palmer—a woman whose enthusiasm and intellectual spark lit up an otherwise apathetic paper proposal; and Thomas Guglielmo, Chad Heap, Terry Murphy, and Elizabeth Anker—for their teaching prowess and academic acumen. -

Firstchoice Wusf

firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • noVemBer 2008 Rolling On the River with Burt Wolf Each week, WUSF TV/DT viewers join Burt Wolf, the genial host of Burt Wolf: Travels & Traditions, on his journeys around the world. Wolf has traveled by plane, train and automobile — but a river cruise is his favorite way to see Europe. This month, on November 12, during a two-hour special, Wolf takes us through the heart of Europe on three voyages along the winding Danube River. In Cruising the Danube, Wolf kicks off his leisurely journey in Budapest and then stops off at the fairy tale castles and hidden streets of Burt Wolf’s two- Bratislava, Dürnstein, Melk, Grein, Linz hour river cruise and Passau before coming full circle to Budapest. On his second expedition, special airs Christmas in Vienna, Wolf sets shore November 12 in Vienna, Austria, exploring ancient Christmas traditions (some edible!) at 8 p.m. and festivities at locations ranging WUSF TV/DT from the magnificent Habsburg castle to Vienna’s celebrated outdoor Channel 16 Christmas markets. On the last leg of the voyage, Austrian Monasteries, Wolf takes us inside the abbeys at Melk and Klosterneuburg — each a fascinating realm of history, tradition and treasure. Wolf concludes his journey with lunch at the restaurant of one of Europe’s most talented chefs. Intrigued? If you’re more than an armchair traveler, you can join Burt Wolf in July 2009 on a Danube River cruise with other WUSF friends. Find more information about this once-in-a-lifetime voyage inside! wusf: FIRST choice WUSF Public WUSF TV/DT Broadcasting: November Highlights A range of media choices WORLDFOCUS brings American audiences a deeper understanding WUSF 89.7 of the stories shaping the world provides NPR news and today. -

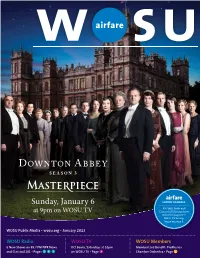

Sunday, January 6 Layout Changes: 89.7 NPR News and at 9Pm on WOSU TV Classical 101 Listings Have Moved to Pages 5–7

Sunday, January 6 LAYOUT CHANGES: 89.7 NPR News and at 9pm on WOSU TV Classical 101 listings have moved to pages 5–7. WOSU TV listings begin on page 8. WOSU Public Media • wosu.org • January 2013 WOSU Radio WOSU TV WOSU Members 6 New Shows on 89.7 FM NPR News DCI Banks, Saturdays at 10pm MemberCard Benefit: ProMusica and Classical 101 • Pages 5 6 7 on WOSU TV • Page 9 Chamber Orchestra • Page 2 ON THE COVER Season 3 of Downton Abbey begins Sunday, WOSU Digital Media – Top Ranked, Always Available and Always Free January 6 on WOSU TV. See pages 3 & 8. How was your holiday? Was your special gift • Through a live blog feature, our news and every graduation a tablet, smart phone or some other mobile digital media teams provided constant on wosu.org. Last device that allows you to email, explore the updates on Election Day from around spring we had Internet, watch video or listen to your favorite Columbus. WOSU Public Media partnered over 1,200 folks radio program on your time? Look soon for a with NPR to provide content to the watching online from 18 countries new app from WOSU Digital, downloadable to “Battleground Blog” and we were publicly including India, Turkey, Poland and South your favorite mobile device. We want to make recognized by NPR’s national leadership for Korea. Families anywhere in the world can it easy for you to take WOSU Public Media providing excellent on-the-ground coverage. see their friends and relatives graduate with you wherever you go! from The Ohio State University through • Did you know you can watch or listen WOSU’s efforts. -

WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2009

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData WGLT Program Guides Arts and Sciences Fall 9-1-2009 WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2009 Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg Recommended Citation Illinois State University, "WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2009" (2009). WGLT Program Guides. 226. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg/226 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in WGLT Program Guides by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLT Radio Faces 2009 GLT presents An evening with NPR's All Things Considered® This year's GLT Radio Faces guest is reporter and All Things Considered®co-host Melissa Block. She is part of the NPR team that won both George Foster RADIO Peabody and Edward R. Murrow Awards for the with sr.2ecial quest Brendan Banaszak coverage of the earthquake in China last year. GLT I FACES Assistant News Director Charlie Schlenker talked with Melissa about part of that experience. Friday, November 6, 2009 Charlie Schlenker: During one story in Chengdu you followed a family through 5:00 - 6:30 pm - Cocktail hour ($100 level only) a long, heart-wrenching day as they searched for relatives. In part of that coverage 6:45 - 9:30 pm - Dinner and presentation your voice carried emotion and distress. C learly, you had the necessary detachment (both ticket levels) to report the story and to find the absolute best way to tell it, but you were recogniz ing and acknowledging the human qualities of what was going on. -

1 ANT 2410 Introduction to Cultural Anthropology University of Florida

1 ANT 2410 Introduction to Cultural Anthropology University of Florida Fall 2019 https://www.nathanwpyle.art/#/strangeplanet/ Instructor and TAs Name: Saul Schwartz Miranda Martin Michael Stoop Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 352-294-1896 Office: Turlington B133 Office W 12-3, and by T 9-11:30, R 9-11:30, T 2:15-3:45, R 1-2:30, Hours: appointment and by appointment and by appointment 2 Course Description Anthropology is the academic discipline that studies humanity across all space and time. Cultural anthropologists study the distinctive ways people create, negotiate, and make sense of their own social worlds in relation to the worlds of others. Through research in places both far away and near to home, anthropologists examine relations and events that influence and determine social belonging and exclusion, whether based in gender, kinship, religion, language, political economy, or historical constructions of race, ethnicity and citizenship. The scope of cultural anthropology is thus broad. Studying culture is crucial to understanding our increasingly connected planet, human relationships, and actions. An anthropological perspective is also essential to efforts which aim to resolve the major crises that confront humanity today. This class provides an introduction to the discipline through a consideration of topics and themes that are not only of vital relevance today but also hold an enduring place in the intellectual tradition of anthropology. The purpose of this class is to increase your familiarity and comfort with concepts of cultural analysis and to show how these notions can increase awareness and understanding of your own and others’ life experiences. -

KPCC Membership Brochure

The Crawford Family Forum The Crawford Family Forum is a welcoming, non-partisan, knowledge- building space where Southern Californians of all backgrounds can engage in the face-to-face exchange of knowledge and ideas that is becoming increasingly rare in the digital era. Nothing can replace real-life interaction—having an opportunity to not just hear, but see others and have direct dialogue goes a long way toward helping build bridges among communities while strengthening, deepening and expanding our public service. For more information on upcoming events in the Crawford Family Patt Morrison with Alonzo Bodden Forum, visit scpr.org/forum. WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUNDAY KPCC Programs 5am Morning Edition Featuring the most NPR with Steve Inskeep in Washington and Renee Motagne and Steve Julian in LA Weekend Edition Saturday Weekend Edition Sunday programming of any station with Scott Simon in Washington and with Audie Cornish in Washington and 9am Shirley Jahad in LA Shirley Jahad in LA in Southern California, Take Two KPCC provides inspiring with Alex Cohen and A Martinez 10am Car Talk Car Talk and entertaining coverage with Tom and Ray Magliozzi with Tom and Ray Magliozzi 11am of important issues on local, Wait, Wait...Don’t Tell Me! Wait, Wait...Don’t Tell Me! with Peter Sagal with Peter Sagal national and international levels. AirTalk with Larry Mantle Noon Off-Ramp Our local shows include Take with John Rabe A Prairie Home Companion with Garrison Keillor Two, a morning news-magazine 1pm BBC News Hour This American Life with a uniquely Angeleno with Ira Glass 2pm The World The Splendid Table Marketplace Money perspective; our popular call- with Lisa Mullins with Lynne Rosetto Kasper with Tess Vigeland in show AirTalk – hosted by 3pm Marketplace with Kai Ryssdal Radio Lab Dinner Party radio veteran Larry Mantle; and with Robert Krulwich and Jad Abumrad with Rico Gagliano and Brendan Newnam weekend favorite Off-Ramp. -

Firstchoice Wusf

firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • maY 2010 A Place in the Sun St. Petersburg: New Place in the Sun celebrates downtown St. Petersburg’s renaissance. This 30-minute documentary, produced by WUSF, was written, directed and narrated by Tampa filmmaker Larry Elliston and underwritten by the Florida Humanities Council. Why St. Petersburg? “It’s a perfect example of the new urbanism that’s blossoming around the country,” says Elliston. “As baby boomers and younger people turn to urban living, St. Petersburg, with its waterfront and historic charm, walkability, and vibrant arts and performance scene, is an ideal destination.” Elliston’s ode to St. Pete “covers a lot of ground,” including a look back at its history, and interviews with the city’s movers and shakers. Airs on WUSF TV, Saturday, May 15, at 8 p.m., and repeats Sunday, May 16, at 9 p.m. from the wusf gm Buy Online and May Support WUSF Greetings! Did you know that every time you buy something s we look forward to the summer online at season, it’s the perfect time to look back Amazon.com, at the busy months behind us. We have A you have the so much good news to share. opportunity to First, we thank you, our dedicated members, help WUSF Public who showed your support during our March radio Broadcasting? and TV membership campaigns. Thanks to you, we If you click the link greeted nearly 1,600 new members and received to Amazon.com pledges of support totaling $550,000. The tough on our website, economic times are starting to take their toll at WUSF Public Broadcasting, and we saw evidence wusf.org, of that during our membership campaigns. -

A Comparative Case Study Examining the Commercial Presence Within Public Radio

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-1999 “All Things Considered”: A Comparative Case Study Examining the Commercial Presence within Public Radio Peter P. Nieckarz III Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Radio Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Nieckarz, Peter P. III, "“All Things Considered”: A Comparative Case Study Examining the Commercial Presence within Public Radio" (1999). Dissertations. 1523. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1523 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “ALL THINGS CONSIDERED”: A COMPARATIVE CASE STUDY EXAMINING THE COMMERCIAL PRESENCE WITHIN PUBLIC RADIO by Peter P. Nieckarz EH A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 1999 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. “ALL THINGS CONSIDERED”: A COMPARATIVE CASE STUDY EXAMINING THE COMMERCIAL PRESENCE WITHIN PUBLIC RADIO Peter P. Nieckarz III, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 1999 This dissertation addresses the commercial presence within public radio. A case study of three NPR affiliate stations was conducted to determine to what extent public radio is being influenced or compromised by increased commercial rationality. It also addresses how they have been able to resist commercialism and remain true to the original ideals of public radio. -

Supporting Documentation Pursuant to Negotiations As Prescribed by the New Jersey Public Broadcasting System Transfer Act

Supporting documentation pursuant to negotiations as prescribed by the New Jersey Public Broadcasting System Transfer Act Request for Proposals • Operation of NJN radio network State of New Jersey State Treasurer Request for Proposals For Operation of the New Jersey Network (NJN) Radio Broadcast Network Issued: February 7, 20~~ Radio Operations RFP Request for Proposals For Operation of the New Jersey Network (NJN) Radio Broadcast Network 1.0 PURPOSE AND INTENT ~.~ This Request for Proposals (" Radio Operations RFP") is being issued by the New Jersey State Treasurer (,'State Treasurer") to solicit proposals from qualified entities (hereinafter referred to as "bidder", "vendor," "firm" or "respondent") to operate and manage all or a portion of the New Jersey Network ("NJN") radio broadcast network (the "NJN Radio Network") which is currently owned and operated by and licensed to the New Jersey Public Broadcasting Authority ("NJPBA"), while at the same time maintaining a New Jersey-focused public broadcasting operation. ~.2 The State Treasurer seeks proposals from potential bidders that will: (a) Operate the NJN Radio Network as a public media news and information service, including the following NJN Radio Network stations ("Station" or "Stations"): (~) WNJT-FM 88.~ FM, Trenton, New Jersey; (2) WNJS-FM 88.~ FM, Berlin, New Jersey; (3) WNJM 89·9 FM, Manahawkin, New Jersey; (4) WNJO 90.3 FM, Toms River, New Jersey; (5) WNJY 89·3 FM, Netcong, New Jersey; (6) WNJN-FM 89.7 FM, Atlantic City, New Jersey; (7) WNJZ 90.3 FM, Cape May Court House, New Jersey; (8) WNJP 88.5 FM, Sussex, New Jersey; (9) WNJB-FM 89.3 FM, Bridgeton, New Jersey; and (~o) New Construction Permie, Bernardsville, New Jersey (upon construction and licensing of the new station). -

Nonprofit Media

SECTION TWO nonprofit media PUBLIC BROADCASTING PEG SPANS SATELLITE LOW POWER FM RELIGIOUS BROADCASTING NONPROFIT NEWS WEBSITES FOUNDATIONS JOURNALISM SCHOOLS EVOLVING NONPROFIT MEDIA 146 Throughout American history, the vast majority of news has been provided by commercial media. For the reasons described in Part One, the commercial sector has been uniquely situated to generate the revenue and profits to sustain labor-intensive reporting on a massive scale. But nonprofit media has always played an important supplementary role. While many nonprofits are small, community-based operations, others are large and some have developed into institutions of tremendous importance in the information sector. The Associated Press is the nation’s largest news wire service, AARP: The Magazine is the largest circulation print magazine in the country, NPR is the largest employer of radio journalists, and Wikipedia is one of the largest information sites on the Internet. Technological changes have transformed noncommercial media as much as they have commercial media. Public TV and radio are morphing into multiplatform information providers. Even before the Internet, nonprofit programming was emerging independent of traditional public TV and radio on satellite, cable television, and low-power FM stations. And now, with the digital revolution, we see an explosion of new nonprofit news websites and mobile phone applications. What is more, our perception of the nonprofit sector must now expand to include: journalism schools that send students into the streets to report; state-level C-SPANs; citizen journalists who contribute to other websites or Tweet, blog and otherwise communicate their own reporting; and even sites born of or shaped by software developers who create “open source” code, free to the public for use and open to amendment by other developers. -

Radiolab and the Micropolitics of Podcasting

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-1-2013 Sound Reason: Radiolab and the Micropolitics of Podcasting Justin M. Eckstein University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Eckstein, Justin M., "Sound Reason: Radiolab and the Micropolitics of Podcasting" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. SOUND REASON: RADIOLAB AND THE MICROPOLITICS OF PODCASTING __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Justin M. Eckstein August 2013 Advisor: Darrin K. Hicks, PhD ©Copyright by Justin M. Eckstein 2013 All Rights Reserved Author: Justin M. Eckstein Title: SOUND REASON: RADIOLAB AND THE MICROPOLITICS OF PODCASTING Advisor: Darrin K. Hicks, PhD Degree Date: August 2013 ABSTRACT Over the past 10 years, the practice of podcasting has migrated from the margins of technological conferences to a central role in popular culture. Podcasting is an Internet-based broadcast medium that relies on Real Simple Syndication (RSS) feeds—a peer subscription service—to automatically retrieve and upload content to a portable MP3 player. In light of its growth and popularity, I ask, ―what is the podcast‘s political potential?‖ In this project, I argue that the podcast has the potential to serve as an instrument of liberal and neurological reasoning.