Nonprofit Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Broadcasting Service Participation in the NPACT Coverage of the Political Primaries and Thetwo and One Half National Conventions

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 072 623 EM 010 708 AUTHOR Stone, Robert R. -TITLE Public Broadcasting Service Participation in the NPACT Coverage of the Political Primaries and theTwo and One Half National Conventions. PUB DATE Nov 72 NOTE 9p.; Paper presented at the National Association of Educational Broadcasters Annual Convention (48th,Las Vegas, Nevada, October 29-November 1, 1972) EDRS PRICE MF -$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Electronic Equipment; *Engineering; *Equipment Utilization; Public Affairs Education; *Public Television; *Video Equipment IDENTIFIERS National Public Affairs Center; *Public Broadcasting Service ABSTRACT Television coverage of the 1972 Presidential Conventions was a complicated, time consuming, exhausting andyet challenging task for the Public Broadcasting Service(PBS). Operating on limited funds and borrowed equipment, PBS had to literally throw together its operation in Miami Beach and still keep tabson'the candidates wandering around the country. The author,an engineering manager with KCET-TV in Los Angeles, outlines the engineering gymnastics that PBS had to go through to provide thecoverage necessary. The video equipment, telephone communications,power requirements, and remote set ups are described in careful technical detail. (MC) My presentation today is on the Public Broadcasting Service participation in the NPACTcoverage of the N1 political primaries and the two andone half national (NJ conventions. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE 4.0 RobertR. act-1e_, KcET, Los khReles OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS SEEN REPRO. r\I National Public Affairs Center for television oucEoEXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIO- N.- requested PBS to assist them in their proposedcoverage 0 :IraSTATEDIATT 43TVII:EICE3SRS 21:: of the forthcoming Democratic and Republican National REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EOU L]. -

August 2018 Program Schedule

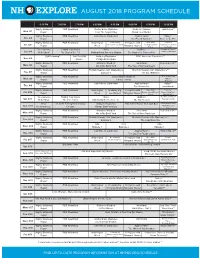

AUGUST 2018 PROGRAM SCHEDULE 6:30 PM 7:00 PM 7:30 PM 8:00 PM 8:30 PM 9:00 PM 9:30 PM 10:00 PM Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Doctor Blake Mysteries Death In Paradise Last Dukes** Wed. 8/1 Report Hear The Angels Sing Melodies of Murder Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Lark Rise to Candleford Agatha Raisin Hillary** Thu. 8/2 Report The Potted Gardener Race to the Pole Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Washington Breaking Big Firing Line with Open Mind Frontline** Fri. 8/3 Report Week Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand Margaret Hoover The Right to Have Separated: Children at Rights the Border The Lawrence Finding Your Roots Nova Outback Wonders of Mexico** Sat. 8/4 Welk Show* The Stories We Tell Making North America: Origins The Kimberley Comes Alive Forests of the Maya Still Dreaming*Ask This Old Antiques Roadshow RFK: American Experience** Sun. 8/5 House Vintage Birmingham Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Midsomer Murders Hinterland Remember Me** Mon. 8/6 Report Not In My Back Yard The Tale of Nant Gwrtheyrn Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Poldark Season 2 On Masterpiece Sherlock Season 4 On Masterpiece** Tue. 8/7 Report Episode 8 The Six Thatchers Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Doctor Blake Mysteries Secrets of the Six Wed. 8/8 Report Family Portrait Wives** Divorced Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Lark Rise to Candleford Agatha Raisin Hillary** Thu. 8/9 Report The Vicious Vet Heartbreak Nightly Business PBS NewsHour Washington Breaking Big Firing Line with Open Mind Frontline** Fri. 8/10 Report Week Lee Daniels Margaret Hoover Documenting A Fascist Documenting Hate: Ascent Charlottesville The Lawrence Finding Your Roots Nova Outback Wonders of Mexico** Sat. -

PUBLIC BROADCASTING: a MEDIUM in SEARCH of SOLUTIONS John W

PUBLIC BROADCASTING: A MEDIUM IN SEARCH OF SOLUTIONS JoHN W. MACY, JR.* INTRODUCTION In its simplest and most comprehensive definition, a communications system is a process in which creative communicators become aware of the expressed and some- times unexpressed needs of the users of the system and responsively collect and provide information, entertainment, and other resources toward the satisfaction of these needs. Despite the often quoted and now popular belief that in electronic com- munications systems "the medium is the message,"' the design of a system in which the message is itself the message-and the medium is merely a means of delivering a diversity of messages of intrinsic value to the users-is a mandate for radio and television in the decade of the 1970s. This is one of the basic philosophies behind the approach of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) as it builds and develops the public sector of broadcasting. Some time ago Robert Oppenheimer was quoted as saying, "What is new is new not because it has never been there before, but because it has changed in quality."2 This is surely what is new about the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. But to understand the nature and direction of the qualitative changes brought about by its creation and activities, it is necessary to look first at what was there before and how the Corporation came into being. I BACKGROUND OF PUBLIC BROADCASTING Over the past fifty years, the American public, through its elected representatives and otherwise, has made a series of choices to encourage the development of a public alternative in the field of communications. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 a Year of Historic Change PAGE 1 the SENTENCING PROJECT ANNUAL REPORT 2007

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 A Year of Historic Change PAGE 1 THE SENTENCING PROJECT ANNUAL REPORT 2007 A YEAR OF HISTORIC CHANGE In 2007 The Sentencing Project took full advantage of the newly emerging bipartisan movement for change occasioned by a renewed focus on evidence-based policies and concern about fiscal realities. Years of organizing by The Sentencing Project and our coalition partners created hope for reform of policies that had been challenged for years with little success. When opportunity knocked, The Sentencing Project was at the door. Historic changes were made to the patently unjust and racially biased federal sentences for crack cocaine offenses, more than twenty years after their adoption. The Sentencing Project has challenged these unfair policies for years with research to highlight the racial disparities produced by the federal mandatory sentences for crack, and the tremendous burden that families from already economically disadvantaged communities experience as a result. Change took place at nearly every point of the system. The U.S. Sentencing Commission lowered the guideline sentences for crack offenses, and subsequently made the change retroactive, making 19,500 people eligible to apply for sentence reductions that are expected to average about two years. The U.S. Supreme Court then ruled that federal judges were permitted to take into account the unfairness of the 100-to-1 quantity ratio for powder vs. crack cocaine when imposing sentences for crack offenses. Reform bills were introduced by Democrats and Republicans in both houses of Congress. The Sentencing Project’s efforts to remove barriers to voting by the more than 5 million people in the United States with felony convictions who are disenfranchised also moved forward. -

As General Managers of Public Radio Stations That Serve Millions of Americans in Communities Large and Small, Urban and Rural And;

As General Managers of Public Radio stations that serve millions of Americans in communities large and small, urban and rural and; As Producers of local, regional and national content aired by stations throughout the nation committed to telling the evolving story of America, its proud history, and its committed citizens; We are writing to express our grave concern regarding the House legislation that would prohibit stations from using any Federal funds to pay for national programming and would eliminate CPB’s Program Fund. By prohibiting the use of Federal funds in any national programming, and in particular, by eliminating the CPB Program Fund, millions of Americans will be deprived of critical national and international news, information and cultural programming that cannot be found elsewhere. Local public radio stations will no longer reliably provide the community information and context so necessary to cities and towns challenged by change and faltering economies. Institutions and projects at risk include: - Radio Bilingüe’s national program service, public radio’s principal source of Latino programming - Koahnik Public Media’ Native Voice 1, public radio’s principal source of Native American programming - Youth Media, the California-based media network of young audio and video producers and a key source of a youth voice in the mass media - The Public Insight Network, American Public media’s expanding project to bring citizen experts into public radio journalism - Independent producers who depend upon the Program Fund for money to support production of series such as StoryCorps and This I Believe - Independent organizations dedicated to innovation, training, and excellence in journalism such as the Public Radio Exchange and the Association of Independents in Radio. -

201201-Kakm-Early Morning

schedule available online: January 2012: Early Morning alaskapublic.org Midnight 12:301:00 1:30 2:00 2:303:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 Coldplay Frontline: Independent Lens: Washington Need To Sun 1/1 Live! Beale Street on New Year's Eve (start 11pm) The Undertaking These Amazing Shadows Week Know Masterpiece Classic: Great Performances: From Vienna: Live From Lincoln Center: Mon 1/2 Downton Abbey - Part 4 The New Year's Celebration 2012 Bernstein and Gershwin Martin Luther: Antiques Roadshow: Masterpiece Classic: Great Performances: Tue 1/3 Sky Island Driven to Defiance Tulsa, OK - Hour 1 Downton Abbey - Part 4 Hugh Laurie: Let Them Talk Frontline: Egypt's Golden Empire: Egypt's Golden Empire: Martin Luther: Antiques Roadshow: Wed 1/4 Opium Brides The Warrior Pharaohs Pharaohs Of The Sun Driven to Defiance Tulsa, OK - Hour 1 Nature: NOVA: NOVA: Egypt's Golden Empire: Egypt's Golden Empire: Thu 1/5 Birds of the Gods Deadliest Volcanoes Deadliest Earthquakes The Warrior Pharaohs Pharaohs Of The Sun Independent Lens: Frontline: NOVA: Nature: Fri 1/6 This Old House Hour Taking Root Opium Brides Deadliest Volcanoes Birds of the Gods Washington Need To Great Performances: Tavis Smiley Reports: Antiques Roadshow: Sat 1/7 This Old House Hour Week Know Celebrate Gershwin Dudamel Tulsa, OK - Hour 1 NOVA: Frontline: Independent Lens: Great Performances: Washington Need To Sun 1/8 Deadliest Volcanoes Opium Brides Taking Root Celebrate Gershwin Week Know Masterpiece Classic: Tavis Smiley Reports: Great Performances: Antiques Roadshow: Nature: Mon 1/9 Downton -

Thinkbright Programming on Time Warner 21 / Digital 17.3 JANUARY & FEBRUARY 2009

ThinkBright programming on Time Warner 21 / Digital 17.3 JANUARY & FEBRUARY 2009 So what is ThinkBright? A Community Asset. / À} Ì vi} i>À} à > v>Þ v `}Ì> i>À} ÃiÀÛVið / i ÃiÀÛVi Ì>À}iÌà ÃÌÕ`iÌÃ] i`ÕV>ÌÀÃ] v>iÃ] >` i>ÀiÀà v > >}ið / i / À} Ì ÃÕÌi v ÃiÀÛVià VÕ`iÃ\ ThinkBright TV ThinkBright Online Special TV and Outreach Initiatives Professional Development for Teachers ThinkBright TV. / à `}Ì> V >i Ài`ivià i>À} vÀ «i«i v > >}ið Ì vviÀà > Ü`i Û>ÀiÌÞ v «À}À>} Ì i`ÕV>Ìi] i} Ìi] >` iÀV ÕÀ VÕÌÞ >` LiÞ`° 7 iÌ iÀ ÞÕ½Ài } vÀ V `Ài½Ã «À}À>Ã] «À}À>Ã Ì ÕÃi ÞÕÀ V>ÃÃÀ] Ài>Ìi` VÌiÌ] À iÀV } iÌiÀÌ>iÌ / À} Ì /6 à vÀ ÞÕ° *ÕÃ] i>V iÛi} / À} Ì vi>ÌÕÀià > `i`V>Ìi` Ì ii Ã Ì >Ì LÕÃÞ ÛiÜiÀÃ Ü ÕÃÌ Ü i Ì tune in to find compelling programs that suit their interests! THEME NIGHTS Sundays / Family & Education 8/&% Mondays / Health & Wellness Tuesdays / Arts & Performance Wednesdays / History & Biography Thursdays / Heritage & Diversity Fridays / Think Globally Saturdays / Science & Nature ThinkBright Online. ÕÀÕà ÌiiÛà ÛiÜiÀà V> v` > ÌÀi>ÃÕÀi ÌÀÛi v iÀV iÌ ÀiÃÕÀVià vÀ ÃV ] i] >` VÕÌÞ ÕÃi° iV ÕÌ / À} ̽à /6 ÃV i`Õi] `i«Ì vÀ>Ì ÃiiVÌ «À}À>Ã] ÌiÀ>VÌÛi >VÌÛÌià >` }>iÃ] ÃÌ>`>À`ÃL>Ãi` iÃà «>Ã] `6`i "i] * - /i>V iÀi 9] }Ài>Ì vÀ>Ì Ã] >` Àit ThinkBright Brings Learning to Light! i>À Ài >Ì ÜÜÜ°/ À} Ì°À} À >``Ì> V«ià v Ì Ã }Õ`i] «i>Ãi VÌ>VÌ iÌÃÞ >ÛÀÃi >Ì Ç£È°n{x°Çäää iÝÌ° Î{x° ThinkBright is made possible through the support of our partners: New York State Music Fund ThinkBright is a service of The Western New York Public Broadcasting Association U Àâà *>â> U *ÃÌ "vvVi Ý £ÓÈÎ U Õvv>] iÜ 9À £{Ó{ä U ǣȰn{x°Çäää ThinkBright programming on Time Warner 21 / Digital 17.3 JANUARY & FEBRUARY 2009 ~~ Workout Series ~~ Classical Stretch Every Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday morning at 6:00 am An effective total body workout of graceful movements which unlocks uncomfortably rigid muscles for a more flexible, relaxed and strengthened body. -

Jodi Gersh Managing Director Development Director Owner/Operator SVP, Audience and Platforms Public Media Company WMUK Conan Venus and Colorado Public Radio Company

Does your community know that you exist? Grow station audience and revenue via increased awareness May 19, 2021 3 pm ET/2 p.m. CT/1 p.m. MT/12 noon PT A Public Media Company Forum | www.publicmedia.co LOGISTICS All attendees are Please use the chat function Please use chat or contact muted by default for questions & comments Steve Holmes for tech support: [email protected] Located at the bottom of the screen Click to open up chat box and ask questions or make comments 2 ABOUT PUBLIC MEDIA COMPANY Public Media Company is a nonprofit consulting firm dedicated to serving public media. We leverage our business expertise to increase public media’s impact across the country. Public Media Company works in partnership with stations in urban and rural communities to find innovative solutions and grow local impact. We have worked with over 300 radio and TV stations in all 50 states www.publicmedia.co 3 AGENDA Why Awareness building matters WMUK Colorado Public Radio Q&A 4 WHY AWARENESS? The more people are aware of your existence as a local media outlet, the more likely they will engage directly with your offerings: • Tuning in over the air • Typing it into the search bar • Listening to a podcast • Visiting your website proactively 5 HOW TO MEASURE AWARENESS First: Ask for un-aided recall “What local television stations do you watch?” “What radio stations do you listen to?” “Where do you go for news?" Second: Ask for aided recall “Which of the following services do you turn to for…” List well-known media in town (newspapers, radio, TV, sites, -

Collection of Television Press Kits, 1958, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c87082fc No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of television press kits, 1958, ca. 1974-ca. 2004 Finding aid prepared by Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 1908 1 television press kits, 1958, ca. 1974-ca. 2004 Title: Collection of television press kits Collection number: 1908 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 9.5 linear ft.(19 boxes and 1 flat box.) Date (inclusive): 1958, ca. 1974-2004 Abstract: This collections documents a variety of television show genres broadcast on networks such as ABC, CBS, NBC, HBO, PBS, SHOWTIME, and TNT. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the caollection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Bam 2016 Annual Report

BAM 2016 2 1ANNUAL REPORT 0 6 BAM’s mission is to be the home for adventurous artists, audiences, and ideas. 3—6 Community, 31–33 GREETINGS DanceMotion USASM, 34–35 Chair Letter, 4 Visual Art, 36–37 President & Executive Producer’s Letter, 5 Membership, 38 BAM Campus, 6 Membership, 37—39 7—35 40—47 WHAT WE DO WHO WE ARE 2015 Next Wave Festival, 8–10 BAM Board, 41 2016 Winter/Spring Season, 11–13 BAM Supporters, 42–45 Also On Stage, 14 BAM Staff, 46–47 BAM Rose Cinemas, 15–20 48—50 First-run Films, 16 NUMBERS BAMcinématek, 17–18 BAM Financial Statements, 49–50 BAMcinemaFest, 19 HD Screenings, 20 51—55 BAMcafé Live, 21–22 THE TRUST BAM Hamm Archives, 23 BET Chair Letter, 52 Digital Media, 24 BET Donors, 53 Education & Humanities, 25–30 BET Financial Statements, 54–55 2 TKTKTKTK Cover: Urban Bush Women in Walking with ‘Trane| Photo: Julieta Cervantes Greetings GREETINGS 3 TKTKTKTK 2016 Winter/Spring | Royal Shakespeare Company in Henry IV Part I | Photo: Richard Termine Change is anticipated, expected, welcomed. — Alan H. Fishman Dear Friends, As you all know, and perhaps celebrated (!), Anne Bogart, Ivo van Hove, Long time trustee Beth Rudin Dewoody As I end my leadership role, I want to I stepped down as chairman of this William Kentridge, and many others. became an honorary trustee. Mark Jackson express my thanks to all I have met and miraculous institution effective December and Danny Simmons, both great trustees, worked with along the way. Together we have 31, 2016. -

Stability and Possible Change in the Japanese Broadcast Market: a Comparative Institutional Analysis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Nishioka, Yoko Conference Paper Stability and Possible Change in the Japanese Broadcast Market: A Comparative Institutional Analysis 14th Asia-Pacific Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Mapping ICT into Transformation for the Next Information Society", Kyoto, Japan, 24th-27th June, 2017 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Nishioka, Yoko (2017) : Stability and Possible Change in the Japanese Broadcast Market: A Comparative Institutional Analysis, 14th Asia-Pacific Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Mapping ICT into Transformation for the Next Information Society", Kyoto, Japan, 24th-27th June, 2017, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/168526 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Education Issue

march 2010 Education Issue Michael Bublé on Great Performances American Masters: I.M. Pei LEARNING IS LIFE’S TREASURE By partnering for the common good we can achieve uncommon results. Chase proudly supports the Celebration of Teaching & Learning with Thirteen/WNET and WLIW21. We salute all educators who dedicate themselves to our children. thirteen.org 1 ducatIon Is at the Our Education Department works heart of everything we year-round on a variety of outreach do at THIRTEEN. As a programs and special initiatives for pioneering provider of students, educators, and parents in New quality television and York State and beyond. Ron Thorpe, Vice web content, unique local President and Director of Education at Eproductions, and innovative educational WNET.ORG, offers an inside look at this and cultural projects, our mission is to vibrant department on page 2. enrich the lives of our community—from Our commitment to education extends pre-schoolers and adult learners to those into the community with Curious George who have a passion for lifelong learning. Saves the Day: The Art of Margret and This special edition of THIRTEEN— H.A. Rey, a fascinating exhibit opening our second annual Education Issue March 14 at The Jewish Museum. See —showcases some of our most exciting page 14 to learn about the exhibit, as well huschka educational endeavors. as special offers available exclusively to jane : : On March 5 and 6, the fifth annual THIRTEEN members. Celebration of Teaching & Learning comes Finally, we’re proud to launch our to New York City. The nation’s premier newly expanded children’s website, Kids llustrations I professional development conference for THIRTEEN (kids.thirteen.org).