Bicameralism and the Dynamics of Lawmaking in Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President, Prime Minister, Or Constitutional Monarch?

I McN A I R PAPERS NUMBER THREE PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW THE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL S~RATEGIC STUDIES I~j~l~ ~p~ 1~ ~ ~r~J~r~l~j~E~J~p~j~r~lI~1~1~L~J~~~I~I~r~ ~'l ' ~ • ~i~i ~ ,, ~ ~!~ ,,~ i~ ~ ~~ ~~ • ~ I~ ~ ~ ~i! ~H~I~II ~ ~i~ ,~ ~II~b ~ii~!i ~k~ili~Ii• i~i~II~! I ~I~I I• I~ii kl .i-I k~l ~I~ ~iI~~f ~ ~ i~I II ~ ~I ~ii~I~II ~!~•b ~ I~ ~i' iI kri ~! I ~ • r rl If r • ~I • ILL~ ~ r I ~ ~ ~Iirr~11 ¸I~' I • I i I ~ ~ ~,i~i~I•~ ~r~!i~il ~Ip ~! ~ili!~Ii!~ ~i ~I ~iI•• ~ ~ ~i ~I ~•i~,~I~I Ill~EI~ ~ • ~I ~I~ I¸ ~p ~~ ~I~i~ PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH.'? PRESIDENT, PRIME MINISTER, OR CONSTITUTIONAL MONARCH? By EUGENE V. ROSTOW I Introduction N THE MAKING and conduct of foreign policy, ~ Congress and the President have been rivalrous part- ners for two hundred years. It is not hyperbole to call the current round of that relationship a crisis--the most serious constitutional crisis since President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. Roosevelt's court-packing initiative was highly visible and the reaction to it violent and widespread. It came to an abrupt and dramatic end, some said as the result of Divine intervention, when Senator Joseph T. Robinson, the Senate Majority leader, dropped dead on the floor of the Senate while defending the President's bill. -

Constitutional Court Judgment No. 5/1981, of February 13 (Unofficial Translation)

Constitutional Court Judgment No. 5/1981, of February 13 (Unofficial translation) The Plenum of the Constitutional Court, comprising the Senior Judges Manuel García-Pelayo y Alonso, Chairman, Jerónimo Arozamena Sierra, Angel Latorre Segura, Manuel Díez de Velasco Vallejo, Francisco Rubio Llorente, Gloria Begué Cantón, Luis Díez-Picazo y Ponce de León, Francisco Tomás y Valiente, Rafael Gómez-Ferrer Morant, Angel Escudero del Corral, Antonio Truyol Serra and Placido Fernández Viagas, has ruled IN THE NAME OF THE KING the following J U D G M E N T In the unconstitutionality appeal against various precepts of the Organic Law 5/1980 of 19 June regulating the Schools Statute proposed by sixty four Senators and represented by the Commissioner T.Q.S.F.C., in which the State Attorney entered an appearance representing the government and with Francisco Tomás y Valiente acting as Rapporteur with the proviso indicated in paragraph 1.15. Conclusions of Law 1. The State Attorney claims the inadmissibility of the appeal on the grounds that the Commissioner appointed by the Senators in this appeal assumes, in virtue of art. 82.1 of the OLCC, their representation, however he cannot also take on its legal direction on which the aforementioned precept is “silent”. In the light of this silence, the State Attorney considers that the norm contained in art. 81.1 of the same Law is applicable, according to which “ad litem representative” and legal director are two distinct persons”. Furthermore, the Government representative bases his argument on the text of art. 864 of the Organic Law of the Judiciary which, according to the State Attorney “prohibits … the simultaneous performance of the duties of legal counsel and the activities of court agent”. -

Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CCoonnssttiittuuttiioonnaall && PPaarrlliiaammeennttaarryy IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn Half-yearly Review of the Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments Preparations in Parliament for Climate Change Conference 22 in Marrakech (Abdelouahed KHOUJA, Morocco) National Assembly organizations for legislative support and strengthening the expertise of their staff members (WOO Yoon-keun, Republic of Korea) The role of Parliamentary Committee on Government Assurances in making the executive accountable (Shumsher SHERIFF, India) The role of the House Steering Committee in managing the Order of Business in sittings of the Indonesian House of Representatives (Dr Winantuningtyastiti SWASANANY, Indonesia) Constitutional reform and Parliament in Algeria (Bachir SLIMANI, Algeria) The 2016 impeachment of the Brazilian President (Luiz Fernando BANDEIRA DE MELLO, Brazil) Supporting an inclusive Parliament (Eric JANSE, Canada) The role of Parliament in international negotiations (General debate) The Lok Sabha secretariat and its journey towards a paperless office (Anoop MISHRA, India) The experience of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies on Open Parliament (Antonio CARVALHO E SILVA NETO) Web TV – improving the score on Parliamentary transparency (José Manuel ARAÚJO, Portugal) Deepening democracy through public participation: an overview of the South African Parliament’s public participation model (Gengezi MGIDLANA, South Africa) The failed coup attempt in Turkey on 15 July 2016 (Mehmet Ali KUMBUZOGLU) -

The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The Westminster Model, Governance, and Judicial Reform Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/82h2630k Journal Parliamentary Affairs, 61 Author Bevir, Mark Publication Date 2008 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM By Mark Bevir Published in: Parliamentary Affairs 61 (2008), 559-577. I. CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-1950 Email: [email protected] II. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Mark Bevir is a Professor in the Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of The Logic of the History of Ideas (1999) and New Labour: A Critique (2005), and co-author, with R. A. W. Rhodes, of Interpreting British Governance (2003) and Governance Stories (2006). 1 Abstract How are we to interpret judicial reform under New Labour? What are its implications for democracy? This paper argues that the reforms are part of a broader process of juridification. The Westminster Model, as derived from Dicey, upheld a concept of parliamentary sovereignty that gives a misleading account of the role of the judiciary. Juridification has arisen along with new theories and new worlds of governance that both highlight and intensify the limitations of the Westminster Model so conceived. New Labour’s judicial reforms are attempts to address problems associated with the new governance. Ironically, however, the reforms are themselves constrained by a lingering commitment to an increasingly out-dated Westminster Model. 2 THE WESTMINSTER MODEL, GOVERNANCE, AND JUDICIAL REFORM Immediately following the 1997 general election in Britain, the New Labour government started to pursue a series of radical constitutional reforms with the overt intention of making British political institutions more effective and more accountable. -

Legislative Process Lpbooklet 2016 15Th Edition.Qxp Booklet00-01 12Th Edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1

LPBkltCvr_2016_15th edition-1.qxp_BkltCvr00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 2:49 PM Page 1 South Carolina’s Legislative Process LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 2 October 2016 15th Edition LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 3 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS The contents of this pamphlet consist of South Carolina’s Legislative Process , pub - lished by Charles F. Reid, Clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. The material is reproduced with permission. LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 4 LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 5 South Carolina’s Legislative Process HISTORY o understand the legislative process, it is nec - Tessary to know a few facts about the lawmak - ing body. The South Carolina Legislature consists of two bodies—the Senate and the House of Rep - resentatives. There are 170 members—46 Sena - tors and 124 Representatives representing dis tricts based on population. When these two bodies are referred to collectively, the Senate and House are together called the General Assembly. To be eligible to be a Representative, a person must be at least 21 years old, and Senators must be at least 25 years old. Members of the House serve for two years; Senators serve for four years. The terms of office begin on the Monday following the General Election which is held in even num - bered years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. -

Representing Different Constituencies: Electoral Rules in Bicameral Systems in Latin America and Their Impact on Political Representation

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Nolte, Detlef; Sánchez, Francisco Working Paper Representing Different Constituencies: Electoral Rules in Bicameral Systems in Latin America and Their Impact on Political Representation GIGA Working Papers, No. 11 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Nolte, Detlef; Sánchez, Francisco (2005) : Representing Different Constituencies: Electoral Rules in Bicameral Systems in Latin America and Their Impact on Political Representation, GIGA Working Papers, No. 11, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182554 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

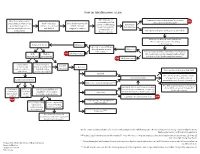

Idea Becomes a Law

How an Idea Becomes a Law Bill is introduced Ideas from many sources: Committee reports “do not pass” or does not STOP and undergoes First constituents, interest groups, Author requests Bill is filed electronically take action on the measure.* and Second Readings. Committee government agencies, bill to be researched with Clerk and is Speaker assigns it to Consideration interim studies, businesses, and drafted. assigned a number. committee(s) or the Governor. Bill reported “do pass” or “do pass as amended.” direct to calendar. Bill moves to General Order. Available to Floor Leader for possible scheduling Returned to House Bill passes on Floor Agenda. Engrossed to Senate: Bill goes through similar process Bill passes in the Senate. ** Floor Consideration: Bill scheduled on Floor Agenda. With Without STOP Bill does not pass Bill is explained, possibly amended, debated, and amendments amendments voted upon. Third Reading and final passage. ** STOP Bill does not pass House refuses House concurs in Enrolled to concur and Senate amendments. To Governor to Governor requests conference Fourth Reading Becomes law on date specified in bill with Senate. and final passage.** Signs bill If no date is specified, and bill contains To Secretary of State emergency clause, bill is effective Conference Committee immediately upon Governor’s signature. Bill becomes law without signature*** If no date is specified, and no emergency Two-thirds vote in each house to override clause, bill becomes law 90 days after Conference CCR filed: CCR electronically filed and veto, unless passed with an emergency, sine die adjournment. Committee Conferees available for Floor Leader Vetoes bill which then requires a three-fourths vote. -

Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-Study*

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-study* Marta Arretche University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil The article distinguishes federal states from bicameralism and mechanisms of territorial representation in order to examine the association of each with institutional change in 32 countries by using constitutional amendments as a proxy. It reveals that bicameralism tends to be a better predictor of constitutional stability than federalism. All of the bicameral cases that are associated with high rates of constitutional amendment are also federal states, including Brazil, India, Austria, and Malaysia. In order to explore the mechanisms explaining this unexpected outcome, the article also examines the voting behavior of Brazilian senators constitutional amendments proposals (CAPs). It shows that the Brazilian Senate is a partisan Chamber. The article concludes that regional influence over institutional change can be substantially reduced, even under symmetrical bicameralism in which the Senate acts as a second veto arena, when party discipline prevails over the cohesion of regional representation. Keywords: Federalism; Bicameralism; Senate; Institutional change; Brazil. well-established proposition in the institutional literature argues that federal Astates tend to take a slow reform path. Among other typical federal institutions, the second legislative body (the Senate) common to federal systems (Lijphart 1999; Stepan * The Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado -

Representing Regions, Challenging Bicameralism: an Introduction by Anna Gamper

DOI: 10.2478/pof-2018-0013 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 2, 2018 ISSN: 2036-5438 Representing Regions, Challenging Bicameralism: An Introduction by Anna Gamper Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 10, issue 2, 2018 © 2018. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Non Commercial-No Derivatives 3.0 License. (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Ed -I DOI: 10.2478/pof-2018-0013 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 2, 2018 Abstract This special issue publishes a number of conference papers presented at the conference ‘Representing Regions, Challenging Bicameralism’ that took place on 22 and 23 March 2018 at the University of Innsbruck, Austria. In this issue, the developments of European bicameral parliaments in (quasi-)federal states are dealt with as well as the political impact of shared rule and alternative models to second chambers. Several papers compare the organizational and functional design of territorial second chambers. Finally, closer examination is given to the EU’s Committee of Regions and the second chambers in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and the UK. Key-words Austria, Belgium, bicameralism, Committee of Regions, Europe, federalism, Germany, Italy, legislation, parliamentarism, regionalism, second chambers, shared rule, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom © 2018. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Non Commercial-No Derivatives 3.0 License. (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Ed -II DOI: 10.2478/pof-2018-0013 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 2, 2018 1. Second Chambers Revisited In the world of modern constitutionalism, second chambers belong to the most archaic institutions whose roots lie in a time before the enactment of the first written constitutions (Luther 2006: 8-13). -

Brasilia and Sao Paulo), 2 April - 5 April 2013

Committee on Foreign Affairs The Secretariat 8 May 2013 OFFICIAL VISIT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS TO BRAZIL (Brasilia and Sao Paulo), 2 April - 5 April 2013 MISSION REPORT MAIN FINDINGS Strengthening dialogue with the Brazilian authorities should one of the priorities of the Committee on Foreign Affairs (AFET) in the context of the EU strategic partnership and the EU-Brazil joint action plan (2012-2014). There are currently more than 30 on-going dialogues under the EU-BR strategic partnership. A Civil Society Forum and a Business Forum take place every year, back to back with EU- BR Summitt. Yet, a true regular and structured dialogue between the EP and the Brazilian Congress is still missing. Visits of MEPs are numerous but still often ad-hoc and unbalanced with BR visits to Europe. A Parliamentary Forum that could meet before Summits could be a useful tool to structure this dialogue and to improve the EU-BR partnership. In reply to the interest shown by both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate to structure better their dialogue with the European Parliament, reflected also in the Brazil-EU Joint Action Plan for 2012-2014 the AFET delegation urged both houses to come up with a joint initiative and promised that it would be met favourable in the European Parliament. The meetings held with governmental representatives confirmed their commitment, announced at the CELAC Summit in January, to submit a negotiating offer on market access regarding the EU- Mercosul Agreement by the end of the year with due account taken of the electoral deadlines of some key players (Paraguay, Venezuela) and the impact of the last economic crisis (Argentina). -

Assessing Brazil's Political Institutions

Comparative Political Studies Volume 39 Number 6 August 2006 759-786 © 2006 Sage Publications Compared to What? 10.1177/0010414006287895 http://cps.sagepub.com hosted at Assessing Brazil’s http://online.sagepub.com Political Institutions Leslie Elliott Armijo Portland State University, Oregon Philippe Faucher Magdalena Dembinska Université de Montréal, Canada A rich and plausible academic literature has delineated reasons to believe Brazil’s democratic political institutions—including electoral rules, the polit- ical party system, federalism, and the rules of legislative procedure—are suboptimal from the viewpoints of democratic representativeness and policy- making effectiveness. The authors concur that specific peculiarities of Brazilian political institutions likely complicate the process of solving societal collec- tive action dilemmas. Nonetheless, Brazil’s economic and social track record since redemocratization in the mid-1980s has been reasonably good in com- parative regional perspective. Perhaps Brazil’s informal political negotiating mechanisms, or even other less obvious institutional structures, provide suffi- cient countervailing influences to allow “governance” to proceed relatively smoothly despite the appearance of chaos and political dysfunction. Keywords: Brazil; democracy; political institutions; policy making, economic reform; developing countries any comparative political scientists and economists now emphasize Mthe incentives for “good governance” created by a country’s set of formal political rules. Though numerous scholars judge Brazil’s political institutions to be almost paradigmatically poorly designed, the country has adopted and implemented politically difficult economic reforms, suggest- ing an apparent puzzle. One’s view of Brazil also influences judgments Authors’ Note: We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of Vicente Palermo, Luiz Carlos Bresser Pereira, Javier Corrales, Peter Kingstone, Stephan Haggard, Adam Przeworski, James Caporaso, William C.