Water Quality and (In)Equality: the Continuing Struggle to Protect Penobscot Sustenance Fishing Rights in Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Federal Clean Water Regulations

History of Federal Clean Water Regulations Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 The Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 was the first major U.S. law to address water pollution. It authorized the Surgeon General to prepare comprehensive programs for eliminating or reducing the pollution of interstate waters and tributaries; and for improving the sanitary conditions of surface and underground waters. This statute also authorized the Federal Works Administrator to assist states, municipalities and interstate agencies in constructing treatment plants to prevent discharges of inadequately treated sewerage into other waters and tributaries. Since 1948, the original law has been repeatedly amended to authorize additional water quality programs, to impose standards and procedures governing allowable discharges and to provide funding for specific goals contained within the statute. Clean Water Act of 1972 November 3, 1952 Cuyahoga River fire (photo credit James Thomas, from Cleveland Press Collection, Cleveland State University Library) It seemed impossible, as a nation, we had allowed our waterways to become so polluted that they caught on fire. The Cuyahoga River in Ohio erupted in fire several times beginning as early as 1868. On June 22, 1969, a Cuyahoga River fire caught the attention of Time Magazine. Time Magazine focused the nation's attention on the pollution of the Cuyahoga River: “Some river! Chocolate-brown, oily, bubbling with subsurface gases, it oozes rather than flows. ‘Anyone who falls into the Cuyahoga does not drown,’ Cleveland's citizens joke grimly. ‘He decays.’” This seminal event spurred an avalanche of pollution control activities ultimately resulting in the Clean Water Act and the creation of the federal and state Environmental Protection Agencies. -

Superfund Laws

Chapter VIII SUPERFUND LAWS In the aftermath of Love Canal and other revelations of the improper disposal of hazardous substances, the federal and state governments enacted the “Superfund” laws to address these problems. Generally these laws address remediation of spills and dumps, rather than regulation of current conduct, and hold parties liable to cleanup contamination resulting from activities that may have been legal. They have resulted in extensive litigation, widespread concerns about environmental liabilities, and expensive cleanups. A. CERCLA The federal Superfund law is entitled the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980 (“CERCLA”), 42 U.S.C. §9601, et seq. It was extensively amended by the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 (“SARA”), and further amendments were made in 2002 by the Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act. 1. Basic Scheme CERCLA provides a framework for the cleanup of the “release” or threatened release” of hazardous substances into the environment. EPA can take action to clean up hazardous substances using funds from the multi-billion dollar “Superfund” (raised by excise taxes on certain chemical feedstocks and crude oil), and then seek reimbursement from “responsible parties.” Alternatively, it can require responsible parties to clean up a site. “Hazardous substances” are defined to include hazardous wastes under RCRA, hazardous substances and toxic pollutants under Clean Water Act §§311(b)(2)(A) and 307(a), 33 U.S.C. 23 §§1321(b)(2)(A) and 1317(a), hazardous air pollutants under Clean Air Act §112, 42 U.S.C. §7412(a), any “imminently hazardous chemical substance or mixture” designated under Toxic Substances Control Act §7, 15 U.S.C. -

Effluent Guidelines/Clean Water Act: U.S

Effluent Guidelines/Clean Water Act: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Notices Availability/Program Plan 14 10/29/2019 The United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) published an October 24th Federal Register Notice referencing the availability of Preliminary Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 14 (“Plan 14”). See 84 Fed. Reg. 57019. Section 304(m) of the Clean Water Act requires that EPA biennially publish a plan for new and revised Walter Wright, Jr. effluent limitations guidelines, after public review and comment. [email protected] Plan 14 is described as identifying: (501) 688.8839 . any new or existing industrial categories selected for effluent guidelines or pretreatment standards and provides a schedule for their development. By way of background, Section 301(b) of the Clean Water Act authorizes EPA to promulgate national categorical standards or limits to restrict discharges of specific pollutants on an industry-by-industry basis. These effluent limits are incorporated into a point source discharger’s National Pollution Discharge and Elimination System permit as a baseline minimum requirement. Clean Water Act effluent limits are derived from research regarding pollution control technology used in the industry. The analysis will include the degree of reduction of the pollutant that can be achieved through the use of various levels of technology. The applicable standard is dictated by the kind of pollutant discharged (i.e., toxic, conventional, or non-conventional) and whether a new or existing point source is involved. Industrial categories are often further divided into subcategories. The effluent limits/conditions for the subcategories will be tailored to the performance capabilities of the wastewater treatment or control technologies used by the subcategory. -

Clean Water Act Section 401 Guidance for Federal Agencies, States and Authorized Tribes

June 7, 2019 UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20460 CLEAN WATER ACT SECTION 401 GUIDANCE FOR FEDERAL AGENCIES, STATES AND AUTHORIZED TRIBES Pursuant to Executive Order 13868, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is issuing this updated guidance to clarify and provide recommendations concerning the implementation of Clean Water Act (CWA) Section 401.1 I. Introduction and Section 401 Certification Overview Congress enacted Section 401 of the CWA to provide states and authorized tribes with an important tool to help protect water quality within their borders in collaboration with federal agencies. Under Section 401, a federal agency may not issue a permit or license to conduct any activity that may result in any discharge into waters of the United States unless a state or authorized tribe where the discharge would originate issues a Section 401 water quality certification verifying compliance with existing water quality requirements or waives the certification requirement. As described in greater detail below, Section 401 envisions a robust state and tribal role in the federal permitting or licensing process, but places limitations on how that role may be implemented to maintain an efficient process that is consistent with the overall cooperative federalism construct established by the CWA. The EPA, as the federal agency charged with administering the CWA,2 is responsible for developing regulations and guidance to ensure effective implementation of all CWA programs, including Section 401. The EPA also serves as the Section 401 certification authority in certain circumstances. Federal agencies that issue permits or licenses subject to a Section 401 certification (federal permitting agencies) also have an important role to play in the Section 401 certification process. -

Compensatory Mitigation Is Required to Replace the Loss of Wetland and Aquatic Resource Functions in the Watershed

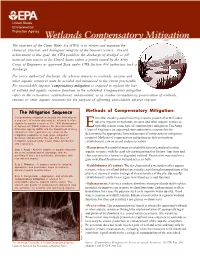

United States Environmental Protection Agency The objective of the Clean Water Act (CWA) is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s waters. Toward achievement of this goal, the CWA prohibits the discharge of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States unless a permit issued by the Army Corps of Engineers or approved State under CWA Section 404 authorizes such a discharge. For every authorized discharge, the adverse impacts to wetlands, streams and other aquatic resources must be avoided and minimized to the extent practicable. For unavoidable impacts, compensatory mitigation is required to replace the loss of wetland and aquatic resource functions in the watershed. Compensatory mitigation refers to the restoration, establishment, enhancement, or in certain circumstances preservation of wetlands, streams or other aquatic resources for the purpose of offsetting unavoidable adverse impacts. The Mitigation Sequence Methods of Compensatory Mitigation: Compensatory mitigation is actually the third step in ven after avoiding and minimizing impacts, projects that will cause a sequence of actions that must be followed to offset impacts to aquatic resources. The 1990 Memorandum adverse impacts to wetlands, streams and other aquatic resources of Agreement (MOA) between the Environmental E typically require some type of compensatory mitigation. The Army Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Army Corps of Engineers (or approved state authority) is responsible for establishes a three-part process, known as the mitigation sequence to help guide mitigation determining the appropriate form and amount of compensatory mitigation decisions and determine the type and level of required. Methods of compensatory mitigation include restoration, mitigation required under Clean Water Act Section establishment, enhancement and preservation. -

Water Quality Standards for Surface Waters

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. PORT GAMBLE 5'KLALLAM TRIBE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS FOR SURFACE WATERS Adopted 8/13/02 A. Standards not in Effect for the Purposes of the Clean Water Act 1. Section 1 Background 2. Section 4 Site Specific Criteria, Provision 4 3. Section 13 Implementation 4. Section 14 Enforcement 5. Section 17 Public Involvement 6. Section 19 Specific Water Quality Criteria for Use Classifications, (3) Recreational and Cultural Use, (a) E. coli criterion for marine waters B. Standards the Tribe has withdrawn Aquatic Life Criteria The Tribe withdrew criteria for both selenium chronic aquatic life criterion and mercury chronic aquatic life criterion. The Tribe will rely on the narrative criteria in Section 7(1) to address these substances. C. Items corrected by the Tribe under the errata sheet submitted to the EPA on 8/31/2005 Section 3- General Conditions A typographical error for marine water occurred in Section 3(4). Section 3(4) (b) should read: For waters in which the salinity is more than ten parts per thousand 95 percent or more of the time, the applicable criteria are the marine water criteria. Section 7- Toxic Substances Arsenic The aquatic life criteria for arsenic have a footnote (h) that states: "The aquatic life criteria refer to the trivalent form only. -

NPDES Permit No. IL0075965 Notice No

NPDES Permit No. IL0075965 Notice No. WH IL0075965-2020 Public Notice Beginning Date: October 5, 2020 Public Notice Ending Date: November 4, 2020 National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permit Program Draft Reissued NPDES Permit to Discharge into Waters of the State Public Notice/Fact Sheet Issued By: Illinois EPA Bureau of Water Division of Water Pollution Control Permit Section Facility Evaluation Unit 1021 North Grand Avenue East Post Office Box 19276 Springfield, Illinois 62794-9276 217/782-3362 Name and Address of Discharger: Name and Address of Facility: Valley View Industries, Inc. Valley View Shale Quarry II 8785 E. 2500 North Rd. 24750 N. 825 East Rd. Cornell, IL 61319 Cornell, IL 61319 (Livingston County) The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA) has made a tentative determination to issue a NPDES Permit to discharge into the waters of the state and has prepared a draft Permit and associated fact sheet for the above named discharger. The Public Notice period will begin and end on the dates indicated in the heading of this Public Notice/Fact Sheet. The last day comments will be received will be on the Public Notice period ending date unless a commentor demonstrating the need for additional time requests an extension to this comment period and the request is granted by the IEPA. Interested persons are invited to submit written comments on the draft permit to the IEPA at the above address. Commentors shall provide his or her name and address and the nature of the issues proposed to be raised and the evidence proposed to be presented with regards to those issues. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 19-257 In the Supreme Court of the United States CALIFORNIA TROUT, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. HOOPA VALLEY TRIBE, ET AL. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR THE FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION IN OPPOSITION NOEL J. FRANCISCO JAMES P. DANLY Solicitor General General Counsel Counsel of Record ROBERT H. SOLOMON Department of Justice Solicitor Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 CAROL J. BANTA [email protected] Senior Attorney (202) 514-2217 Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Washington, D.C. 20426 QUESTION PRESENTED The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (Com- mission) has authority to issue licenses for the construc- tion, operation, and maintenance of hydroelectric pro- jects on jurisdictional waters. See 16 U.S.C. 797(e). If a proposed hydroelectric license “may result in any dis- charge into the navigable waters” of the United States, the Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq., requires that the applicant provide the Commission with “a cer- tification from the State in which the discharge origi- nates.” 33 U.S.C. 1341(a)(1). The statute further states that “[i]f the State * * * fails or refuses to act on a re- quest for certification, within a reasonable period of time (which shall not exceed one year) after receipt of such request, the certification requirements of this sub- section shall be waived with respect to such Federal ap- plication.” Ibid. The question presented is: Whether the court of appeals correctly determined that California and Oregon waived water quality certi- fication under 33 U.S.C. -

Prohibit State Agencies from Regulating Waters More Stringently Than the Federal Clean Water Act, Or Limit Their Authority to Do So

STATE CONSTRAINTS State-Imposed Limitations on the Authority of Agencies to Regulate Waters Beyond the Scope of the Federal Clean Water Act An ELI 50-State Study May 2013 A PUBLICATION OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL LAW INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, DC ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by the Environmental Law Institute (ELI) with funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under GSA contract No. GS-10F-0330P (P.O. # EP10H000246). The contents of this report do not necessarily represent the views of EPA, and no official endorsement of the report or its findings by EPA may be inferred. Principal ELI staff contributing to the project were Bruce Myers, Catherine McLinn, and James M. McElfish, Jr. Additional research and editing assistance was provided by Carolyn Clarkin, Michael Liu, Jocelyn Wiesner, Masumi Kikkawa, Katrina Cuskelly, Katelyn Tsukada, Jamie Friedland, Sean Moran, Brian Korpics, Meredith Wilensky, Chelsea Tu, and Kiera Zitelman. ELI extends its thanks to Donna Downing and Sonia Kassambara of EPA, as well as to Erin Flannery and Damaris Christensen. Any errors and omissions are solely the responsibility of ELI. The authors welcome additions, corrections, and clarifications for purposes of future updates to this report. About ELI Publications— ELI publishes Research Reports that present the analysis and conclusions of the policy studies ELI undertakes to improve environmental law and policy. In addition, ELI publishes several journals and reporters—including the Environmental Law Reporter, The Environmental Forum, and the National Wetlands Newsletter—and books, which contribute to education of the profession and disseminate diverse points of view and opinions to stimulate a robust and creative exchange of ideas. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 99-1178 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________ SOLID WASTE AGENCY OF NORTHERN COOK COUNTY, Petitioner, v. UNITED STATES ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, ET AL., Respondents. __________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit __________ REPLY BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER __________ TIMOTHY S. BISHOP SHARON SWINGLE Mayer, Brown & Platt Counsel of Record 1909 K Street, N.W. KASPAR J. STOFFELMAYR Washington, D.C. 20006 Mayer, Brown & Platt (202) 263-3000 190 South LaSalle Street Chicago, IL 60603 (312) 782-0600 GEORGE J. MANNINA, JR. O’Connor & Hannan, L.L.P. 1666 K Street, N.W. Suite 500 Washington, D.C. 20006 (202) 887-1400 Counsel for Petitioner 1 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................ ii ARGUMENT .................................... 1 CONCLUSION ................................. 20 iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page Cases: Andrus v. Allard, 444 U.S. 51(1979) .................. 4 Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter of Communities for a Greater Oregon, 515 U.S. 687 (1995) ......... 10 Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983) ...................................... 15 Burlington Truck Lines v. United States, 371 U.S. 156 (1962) .......................... 6, 7 Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U.S. 238 (1936) ....... 4, 5 Central Bank v. First Interstate Bank, 511 U.S. 164 (1994) ........................... 16 Consumer Prods. Safety Comm’n v. GTE Sylvania, Inc., 447 U.S. 102 (1980) ........... 13 Donnelly v. United States, 228 U.S. 243 (1913) ........ 11 Edward J. DeBartolo Corp. v. Florida Gulf Coast Bldg. & Constr. Trades Council, 485 U.S. 568 (1988) ............................ 1 FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 120 S. -

Public Law 95-217 95Th Congress an Act Dec

91 STAT. 1566 PUBLIC LAW 95-217—DEC. 27, 1977 Public Law 95-217 95th Congress An Act Dec. 27, 1977 ip^ amend the Federal Water Pollution Control Act to provide for additional [H.R. 3199] authorizations, and for other purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the Clean Water Act United States of America in Congress assembled, That this Act may of 1977. be cited as the "Clean Water Act of 1977". 33 use 1251 note. SHORT TITLE 33 use 1251 SEC. 2. Section 618 of the FederallVater Pollution Control Act is "•^t®- amended to read as follows: uSHOR T TITLE "SEC. 518. This Act may be cited as the 'Federal Water Pollution Control Act' (commonly referred to as the Clean Water Act).". AUTHORIZATION APPROVAL 33 use 1376 SEC. 3. Funds appropriated before the date of enactment of this Act note, for expenditure during the fiscal year ending June 30,1976, the transi tion quarter ending September 30,1976. and the fiscal year ending Sep tember 30, 1977, under authority of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act, are hereby authorized for those purposes for which appropriated. AUTHORIZATION EXTENSION 33 use 1254. SEC. 4. (a) Section 104(u) (2) of the Federal Water Pollution Con trol Act is amended by striking out "1975" and inserting in lieu thereof "1975, $2,000,000 for fiscal year 1977, $3,000,000 for fiscal year 1978, $3,000,000 for fiscal year 1979, and $3,000,000 for fiscal year 1980,". (b) Section 104(u) (3) of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act is amended by striking out "1975" and inserting, in lieu thereof "1975, $1,000,000 for fiscal year 1977, $1,500,000 for fiscal year 1978, $1,500,000 for fiscal year 1979, and $1,500,000 for fiscal year 1980,". -

Federal Water Pollution Control Act [33 USC 1251

Page 313 TITLE 33—NAVIGATION AND NAVIGABLE WATERS CHAPTER 26—WATER POLLUTION Sec. PREVENTION AND CONTROL 1301. Sewer overflow control grants. SUBCHAPTER III—STANDARDS AND SUBCHAPTER I—RESEARCH AND RELATED ENFORCEMENT PROGRAMS 1311. Effluent limitations. Sec. 1312. Water quality related effluent limitations. 1251. Congressional declaration of goals and policy. 1313. Water quality standards and implementation 1252. Comprehensive programs for water pollution plans. control. 1313a. Revised water quality standards. 1252a. Reservoir projects, water storage; modifica- 1314. Information and guidelines tion; storage for other than for water qual- 1315. State reports on water quality. ity, opinion of Federal agency, committee 1316. National standards of performance. resolutions of approval; provisions inap- 1317. Toxic and pretreatment effluent standards. plicable to projects with certain prescribed 1318. Records and reports; inspections. water quality benefits in relation to total 1319. Enforcement. project benefits. 1320. International pollution abatement. 1253. Interstate cooperation and uniform laws. 1321. Oil and hazardous substance liability. 1254. Research, investigations, training, and infor- 1321a. Prevention of small oil spills. mation. 1321b. Improved coordination with tribal govern- 1254a. Research on effects of pollutants. ments. 1255. Grants for research and development. 1321c. International efforts on enforcement. 1256. Grants for pollution control programs. 1322. Marine sanitation devices. 1257. Mine water pollution control demonstrations. 1323. Federal facilities pollution control. 1257a. State demonstration programs for cleanup of 1324. Clean lakes. abandoned mines for use as waste disposal 1325. National Study Commission. sites; authorization of appropriations. 1326. Thermal discharges. 1258. Pollution control in the Great Lakes. 1327. Omitted. 1259. Training grants and contracts. 1328. Aquaculture. 1260. Applications; allocation. 1329. Nonpoint source management programs.