How Can Accelerators in South America Evolve to Support Start-Ups in a Post-Covid-19 World?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Startups in Greece 2019

START UPS IN GREECE 2019 Re-mapping the investments landscape ANNUAL REPORT IN PARTNERSHIP WITH CON TENForeword 03 About EIT Digital 04 Found.ation 04 TS Velocity.Partners 04 Executive Summary Limitations and Methodology 05 The Greek Digital Economy 06 A statement from the Ministry of Development and Investments 11 The EquiFund’s Impact Short presentation of all VC funds and their investments so far 12 A statement from the EIF 23 The Greek startup ecosystem An analysis of the startups in the pre-seed and seed stages 24 Startup funding and exits Top of 2019 most funded/exits 36 Key takeaways and Suggestions 42 FOREWORD 10 year in & the next decade dominate international markets, but also attract of the Greek Startup internationally acclaimed investors like Bain Capital Ecosystem and Balderton. As the new decade reaches According to our report, for every euro invested from its closure, we cannot but an Equifund family fund, Greek startup companies question what is next have raised another two euro from private investors for the greek startup and international funding schemes. This is a very ecosystem. Although it clear and bold vote of confidence for the quality started as a clear underdog of the entrepreneurial level we as Greeks have to for the first decade of its offer. Moreover, this year, we recorded an increase existence, the greek startup in early stage (pre-seed and seed) investments; a Dimitris Kalavros-Gousiou community has undertaken development that strengthens the belief we need Investor, co-founder an impressive acceleration to invest more in the very early stage of the venture and partner of Velocity. -

What Gets an Idea Included? the Impact of Group Dynamics on Idea Inclusion in Team Meetings

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Fakultät für Informatik Lehrstuhl für Wirtschaftsinformatik (I 17) Univ.-Prof. Dr. Helmut Krcmar What Gets an Idea Included? The Impact of Group Dynamics on Idea Inclusion in Team Meetings Tobias Schlachtbauer, M.Sc. Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Informatik der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Florian Matthes Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Prof. Dr. Helmut Krcmar 2. Prof. Dr. Michael Schermann Die Dissertation wurde am 24.05.2018 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Informatik am 26.09.2018 angenommen. Abstract I Abstract Motivation: Working in teams on solving complex tasks, including software development or service design, is common in today’s organizations. All these tasks require some creativity. This is especially true if the creation of innovative solutions to a problem is required. On the one hand, research findings suggest that teams are preferable to individuals for solving problems because the diverse points of view might spark more creative solutions. On the other hand, groups are found being prone to detrimental behaviors like groupthink or choosing not the best design. The disadvantages of groups are often attributed to misunderstandings due to the divers disciplinary or cultural background of the team members. Yet, other issues might be at play that leads to situations in which a team does not realize the full potential of the individual team members. Research Method: Our study combines ethnographic observation with grounded theory to investigate how proposed solutions for an assigned design problem evolve over the course of a project. -

Read Dissertation

Doctoral Dissertation: The Journey towards a Growing Diffusion of Entrepreneurship Learning and Culture in Society Written by: Mirta Michilli Role DETAILS Author Name: Mirta Michilli, PhD Year: 2019 Title: The Journey towards a Growing Diffusion of Entrepreneurship Learning and Culture in Society Document type: Doctoral dissertation Institution: The International School of Management (ISM) URL: https://ism.edu/images/ismdocs/dissertations/michilli-phd- dissertation-2019.pdf International School of Management Ph.D. Program The Journey towards a Growing Diffusion of Entrepreneurship Learning and Culture in Society PhD Dissertation PhD candidate: Mirta Michilli 21st December 2019 Acknowledgments I wish to dedicate this work to Prof. Tullio De Mauro who many years ago believed in me and gave me the permission to add this challenge to the many I face every day as General Director of Fondazione Mondo Digitale. The effort I have sustained for many years has been first of all for myself, to satisfy my desire to learn and improve all the time, but it has also been for my fifteen year old son Rodrigo, who is building his life and to whom I wish the power of remaining always curious, hungry for knowledge, and capable of working hard and sacrificing for his dreams. I could have not been able to reach this doctorate without the support of my family: my mother, for having being present all the time I needed to be away, my sister, for showing me how to undertake continuous learning challenges and, above all, my beloved husband to whom I owe most of what I know and for dreaming with me endlessly. -

Research on Technology Entrepreneurship and Accelerators

RESEARCH ON TECHNOLOGY ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND ACCELERATORS Essays on the emerging phenomenon of accelerators across Europe PhD Dissertation Jonas Van Hove 2018 Advisors: Prof. Dr. Bart Clarysse and Prof. Dr. Petra Andries A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Applied Economics Academic year: 2017 – 2018 1 Copyright © 2018 by Jonas Van Hove All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. 2 DOCTORAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Prof. dr. Bart Clarysse Ghent University, Belgium & ETH Zurich, Switzerland – administrative supervisor Prof. dr. Petra Andries Ghent University, Belgium – promotor Prof. dr. Johan Bruneel KU Leuven Campus Kortrijk, Belgium 3 4 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS AND CONFERENCE PRESENTATIONS BASED ON THIS DOCTORAL RESEARCH Journal publications Pauwels, C., Clarysse, B., Wright, M., & Van Hove, J. (2016). Understanding a new generation incubation model: The accelerator. Technovation, 50: 13-24. Book chapters Clarysse, B., Wright, M., & Van Hove, J. (2016). A Look inside Accelerators in the United Kingdom: Building Businesses. Technology Entrepreneurship and Business Incubation: Theory, Practice, Lessons Learned. Imperial College Press, UK. Vanaelst, I., & Van Hove, J. (2017). Revolutionizing entrepreneurial ecosystems through a European accelerator policy. Accelerators: Successful Venture Creation and Growth. Edward Elgar Publishing. Van Hove, J., & Vanaelst, I. (2017). Revolutionizing entrepreneurial ecosystems through national and regional accelerator policy. Accelerators: Successful Venture Creation and Growth. Edward Elgar Publishing. Working papers Van Hove, J. (2017). -

VC Daily: Cargill Joins Probiotics Company's Fundraising; 500 Startups Hosts Virtual Pitches; Edison Eyes Fund Good Day

FEBRUARY 08, 2021 VC Daily: Cargill Joins Probiotics Company's Fundraising; 500 Startups Hosts Virtual Pitches; Edison Eyes Fund Good day. Last week, startup guts with a strain of bacteria called B. eliminated commissions, making buying a accelerator 500 Startups held its second infantis, which protects newborns and share of stock about as easy as posting a virtual demo day since the pandemic nourishes a healthy gut. Because of photo on Instagram. It worked. During upended the event. Roughly two dozen factors such as rising antibiotic use in the pandemic, throngs of amateur startups, which joined the accelerator recent decades, many mothers don't have investors—homebound, bored and flush earlier this year, made rapid-fire two B. infantis to pass on their children, with stimulus checks—opened Robinhood minute pitches to investors who tuned according to Evolve. accounts to experience the market's in. * Cargill plans to help Evolve thrills. By the end of December, the firm explore new applications for its probiotic had amassed about 20 million users, Pawsh, a mobile pet-grooming technology, including human and animal according to people close to it, and weeks service, pitched investors on its uses. later its app hit the top of download "groomer-first business model" which 65% charts. It should have been a moment to Chief Executive Officer Karthik Roughly the share of lithium-ion celebrate. Instead, a recent Thursday Naralasetty said is experiencing 30% batteries that come from China. began with a panicked, predawn phone revenue growth. Edison Partners Eyes $425 Million call informing Mr. Tenev that Robinhood for Latest Fund needed to come up with billions of dollars Drover.ai pitched a hardware Growth-equity firm Edison if it wanted to open for business in a few device that scooter-sharing fleets could Partners is preparing to launch its latest hours. -

The Startup Factories. the Rise of Accelerator Programmes

Discussion paper: June 2011 The Startup Factories The rise of accelerator programmes to support new technology ventures Paul Miller and Kirsten Bound NESTA is the UK’s foremost independent expert on how innovation can solve some of the country’s major economic and social challenges. Its work is enabled by an endowment, funded by the National Lottery, and it operates at no cost to the government or taxpayer. NESTA is a world leader in its field and carries out its work through a blend of experimental programmes, analytical research and investment in early- stage companies. www.nesta.org.uk Executive summary Over the past six years, a new method of incubating technology startups has emerged, driven by investors and successful tech entrepreneurs: the accelerator programme. Despite growing interest in the model from the investment, business education and policy communities, there have been few attempts at formal analysis.1 This report is a first step towards a more informed critique of the phenomenon, as part of a broader effort among both public and private sectors to understand how to better support the growth of innovative startups. The accelerator programme model comprises five main features. The combination of these sets it apart from other approaches to investment or business incubation: • An application process that is open to all, yet highly competitive. • Provision of pre-seed investment, usually in exchange for equity. • A focus on small teams not individual founders. • Time-limited support comprising programmed events and intensive mentoring. • Cohorts or ‘classes’ of startups rather than individual companies. The number of accelerator programmes has grown rapidly in the US over the past few years and there are signs that more recently, the trend is being replicated in Europe. -

OGC 2015 Programbook.Pdf

CONFERENCE HIGHLIGHT Conference Opening 09:15 - 10:00, 29 August 2015, Saturday At Osmanthus Hall Plenary Talk I Optical fibres: The next Generation – Prof. Sir David Payne, University of Southampton, UK 10:00 - 10:45, 29 August 2015, Saturday At Osmanthus Hall Plenary Talk II Using Metamaterials to Manipulate Light – Prof. Che-Ting Chan, HKUST, HK 11:15 - 12:00, 29 August 2015, Saturday At Osmanthus Hall Best Paper Award Session 11:15 - 12:00, 29 August 2015, Saturday At Lotus 4, Lotus 5 & Lotus 6 Workshop 1. Fiber-Based Technologies 09:30 - 12:20, 30 August 2015, Sunday At Rose 3 Workshop 2. Optoelectronics Technopreneurship 09:30 - 12:20, 30 August 2015, Sunday At Rose 2 Workshop 3. Metro Optical Transmission (Huawei) 13:30 - 17:00, 29 August 2015, Saturday At Rose 3 2 TABLE OF CONTENT CONFERENCE HIGHLIGHT .................................................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF CONTENT ............................................................................................................................................. 3 WELCOME MESSAGE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 SPONSORSHIP ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 ORGANIZING COMMITTEE.................................................................................................................................. -

GUIDE of BEST PRACTICES for ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION Intellectual Output IO3

SUCCESS4ALL project: E-course on Entrepreneurship Skills - an inclusive education approach GUIDE OF BEST PRACTICES FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION Intellectual Output IO3 1 SUCCESS4ALL project: E-course on Entrepreneurship Skills - an inclusive education approach Acknowledgement This report forms part of the Intellectual Outputs from a project called "Success4all" which has received funding from the European Union’s ERASMUS+ program under grant agreement n°2016-1- FR01-KA2013-024269. The Community is not responsible for any use that might be made of the content of this publication. Success4all aims at developing an inclusive e-learning platform on entrepreneurship. The project runs from September 2016 to February 2019, it involves 8 partners and is coordinated by PSB. More information on the project can be found at Success4allStudents.eu. 2 SUCCESS4ALL project: E-course on Entrepreneurship Skills - an inclusive education approach Overview As one surveys of the worldwide business landscape exemplifies, one will find that most of the businesses have less than 100 employees. In more than half of the countries worldwide, over 50% of all employees work in small businesses, and this contributes at least half of the gross domestic product for those countries. Small businesses tend to be more in-tune with customer needs, more flexible to meet those needs, and more responsive to those needs as they grow and change. The entrepreneurial nature of these small companies is a strong source of innovation in their respective economy, but teaching and encouraging the entrepreneurial mindset requires a different set of educational techniques than instruction in other subjects. In the following guide we will present a series of “best practices” for the instruction of entrepreneurship. -

Creating LAIA Foreword

Creating LAIA Foreword The lack of capital and support has been a constant refrain a feasibility study on the potential of a women-focused heard from female entrepreneurs at every stage of growth. LA incubator and accelerator, hence this publication A recent report by JPMorgan Chase and The Initiative for of Creating LAIA: The Feasibility of a Women-Focused a Competitive Inner City (ICIC) found that women (and Incubator & Accelerator in Los Angeles. minorities) “are not participating in high-tech incubators and accelerators at the same rates as their white, male Creating LAIA is the definition of collaboration - what counterparts.” women do organically. Although it was ofcially and adroitly written by We Are Enough Executive Director and After I gave my 2015 TEDx Talk, “Why You Should be Sexist Co-founder, Delilah Panio, the final product was birthed by with Your Equity Capital,” I was surprised by how many many. Along with the women entrepreneurs and women- women entrepreneurs approached and requested to meet focused incubator and accelerator leadership listed in with me – each emotionally describing their reactions to the appendix, we have had conversations with or have what I thought was the unemotional subject of finance and listened to many female investors and entrepreneurs who money. The majority of these women were small business have informed the conclusions reached in Creating LAIA. owners who articulated stories of the difculty in growing To name a few – Monica Dodi, Kara Nortman, Efe Epstein, their businesses, specifically the lack of support and Dana Settle, Kesha Cash, Carman Palafox, Noramay capital. I soon learned that many women had an emotional Cadena, Adena Smith, Diane Manuel, Ana Quintana, Darya and insecure relationship with money. -

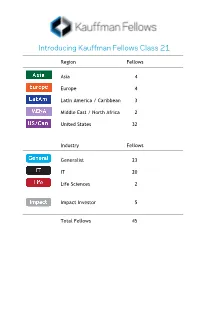

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21

Introducing Kauffman Fellows Class 21 Region Fellows Asia 4 Europe 4 Latin America / Caribbean 3 Middle East / North Africa 2 United States 32 Industry Fellows Generalist 23 IT 20 Life Sciences 2 Impact Investor 5 Total Fellows 45 NICOLAS BERMAN Partner KaszeK Ventures [email protected] +54 (11) 4786-3426 www.kaszek.com Professional Nik is a Partner at KaszeK Ventures, a venture capital firm investing in high-impact technology-based companies whose main focus is Latin America. In addition to capital deployment, the firm actively supports its portfolio companies through value-added strategic guidance and hands-on operational help, leveraging its partners’ successful entrepreneurial backgrounds and extensive network. Before joining KaszeK Ventures, Nik worked for 13 years at MercadoLibre, where he was VP of Advertising, VP of Marketing, Marketing Manager, and covered several roles in the company’s technology and product areas. He led several key projects in search, business intelligence (BI), user experience (UX), and SEO, and created the company’s affiliate program, which is the largest in Latin America. During all these years, Nik has also been a very active advisor and angel investor in the Latin American startup scene. Prior to MercadoLibre, Nik was a Commercial Manager at LG Electronics, where he received the “LG Global Hit Idea” award for his innovative thinking. He currently sits on the boards of several technology companies, including DogHero, Contabilizei, and Pitzi. Education/Personal Nik earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from the University of Buenos Aires (Argentina). He served as President of AMDIA (Argentina’s direct marketing association), received an Echo Award by the DMA in 2000, is currently an active mentor for Endeavor Argentina, and sits in the board of Educatina, a company focused on democratizing high-quality education across Latin America. -

Green Fintech Network Stellt Aktionsplan Vor

Staatssekretariat für internationale Finanzfragen SIF Green Fintech Network stellt Aktionsplan vor Das neue Netzwerk von Startups und Experten aus dem Bereich Green Fintech hat am 8. April 2021 einen Aktionsplan für einen grünen und innovativen Finanzplatz Schweiz vorgestellt. Dies steht im Einklang mit dem Ziel des Bundesrates, die Schweiz zu einem globalen Leader für digitale und nachhaltige Finanzdienste zu machen. Das Green Fintech Network wurde im November 2020 unter Mithilfe des Staatssekretariats für internationale Finanzfragen SIF gegründet. Im nun vorgestellten Aktionsplan werden 16 konkrete Vorschläge für eine zukunftsträchtige Kombination von digitaler Technologie und nachhaltigem Finanzwesen präsentiert. Sie reichen vom Errichten einer Plattform für Nachhaltigkeitsdaten über die Lancierung einer Innovation Challenge für Green Fintech Startups bis zur Förderung von Open Finance oder dem Ausbau von Finanzierungsmöglichkeiten für Green Fintechs. Das Netzwerk versteht seine Vorschläge als konkreten Anreiz für Behörden, Verbände, Wissenschaft und Unternehmen, um erfolgversprechende innovative Umsetzungen anzustreben. An einem Round Table unter der Leitung von Bundesrat Ueli Maurer sollen diese Vorschläge am 19. Mai 2021 breit diskutiert werden. Green Fintech Action Plan 2021 (PDF, 6 MB, 08.04.2021) Letzte Änderung 08.04.2021 https://www.sif.admin.ch/content/sif/de/home/dokumentation/fokus/green-fintech-action- plan.html Harnessing the Power of Digital Finance for Sustainable Financial Markets Green fintech action plan: 16 proposals -

Swiss Startup Conference 2021,Deep-Tech Start

San Diego’s Thriving Startup Community Startup San Diego is the official Non-Profit Organization to support individuals building startups in San Diego, to represent the interests of entrepreneurs, celebrate successes, and foster a cohesive and collaborative community. Eligibility Startups Entrepreneurs Founders Innovators Investors Mentors Aspiring Talents Students Also, read about Startup Funding Options for Business Benefits Educating – startups on how to validate and grow. Fostering – relationships between startups and local universities, government, vendors, and organizations. Facilitating – companies and aspiring talent to the most appropriate resources. Growing – the quantity and quality of companies started in the region. Application Process Click here to apply For more Interesting Content and other Opportunities Visit and Follow/Like Us On Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram Meet the Top Startup Mentors and Graduates in Berlin (Open Zoom Meeting) Many people don’t know there is an abundance of Berlin startup mentors, graduates, and experts that are ready (and willing) to help founders launch and grow their business. At this upcoming open Zoom meeting by The Founder Institute, you can meet and build relationships with some of Berlin’s startup mentors, graduates, and advisors, including the Local Leaders of the Berlin Virtual Fall 2021 program. The majority of this event will be devoted to answering your questions and giving you feedback on your business, so come ready! Eligibility Anyone interested in building a startup in Berlin Entrepreneurs with questions about starting and growing a technology business Anyone interested in learning more about the Founder Institute Berlin Virtual Fall 2021 program Benefits An opportunity to meet and build relationships with some of Berlin’s startup mentors, graduates, and advisors, including the Local Leaders of the Berlin Virtual Fall 2021 program.