Other Relevant Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office Market Review 2015 Update Final Report

Office Market Review 2015 Update Final Report On Bath City Centre on behalf of Bath and North East Somerset Council Prepared by Lambert Smith Hampton Tower Wharf Cheese Lane Bristol BS2 0JJ Tel: 0117 926 6666 Date: October 2015 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1. SUPPLY OF OFFICE ACCOMMODATION 5 1.1 Location 5 1.2 Supply 5 1.3 Grade of offices 5 1.4 The Office stock 6 1.5 Vacancy rate 1.6 Impact of Permitted development rights 1.7 Take Up 9 1.8 Additional supply 10 2. DEMAND 2.1 Sources of demand 12 2.2 Latent and suppressed demand 12 2.3 Requirement of modern occupiers 13 2.4 Attraction of Bath city centre to office occupiers 14 3. DELIVERY OF OFFICE SPACE 3.1 Why has Bath not delivered private sector investment. 16 3.2 What should Bath be seeking to deliver. 16 3.3 Opportunities. 18 4. CONCLUSIONS & OBSERVATIONS 4.1 General 21 4.2 Bath Occupiers 21 4.3 Potential Occupiers 21 4.4 The Future 22 Appendices Appendix 1 Area Plan Appendix 2 Bath overview and statistics Appendix 3 Bath Office Occupiers Survey Bath & North East Somerset Council 2 October 2015 Office Market Review INTRODUCTION Lambert Smith Hampton has been requested by Bath and North-East Somerset Council to provide an up dated market analysis of the existing supply and demand for offices in Bath City Centre. This analysis will be used to help inform and shape policy. It will also feed into the potential delivery of new office space and direction of the Council’s Place-Making Plan. -

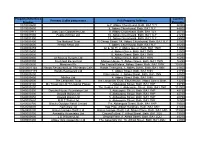

Property Reference Number Primary Liable Party Name Full Property

Property Reference Current Primary Liable party name Full Property Address Number Rateable 0010000600 6-7, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 30000 0010000800 8, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 44500 0010000911 Jody Cory Goldsmiths Ltd 9, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 20750 0010001000 Fudge Kitchen Ltd 10, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 21250 0010001300 13, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 25000 0010001400 The National Trust 15 Cheap Street, 14, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 51000 0010500000 Presto Retail Ltd 7, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 38250 0020000255 Gr & 1st Fl, 2, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 13000 0020000400 4, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 12500 0020000500 5, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 28250 0020000800 At Sixes & Sevens Ltd 8, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 16250 0020000900 Freshford Bazaar Ltd Mignon House, 9, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 16250 0020500000 Marstons Plc The Crystal Palace, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 103000 00300001165 Hands Restaurant Ltd T/A Hands Cafe Hands Tearooms, 1, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN 21500 00300001175 Hands Restaurant Ltd 1, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN 21750 0030000200 Elton House, 2, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN 24500 0030000400 Mirifice Ltd 4, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN 31750 0030000500 The Landmark Trust The Landmark Trust, Elton House, Abbey Street, Bath, 13250 0040000100 My Travel Uk Ltd T/A Going Places 1, Abbeygate Street, Bath, BA1 1NP 39750 0040000200 The Golden Cot, 2, Abbeygate Street, Bath, BA1 1NP 112000 0040000300 Dorothy House Foundation Ltd 3, Abbeygate Street, Bath, BA1 1NP 45750 0040000400 -

Copy of NNDR Assessments Exceeding 30000 20 06 11

Company name Full Property Address inc postcode Current Rateable Value Eriks Uk Ltd Ber Ltd, Brassmill Lane, Bath, BA1 3JE 69000 Future Publishing Ltd 1st & 2nd Floors, 5-10, Westgate Buildings, Bath, BA1 1EB 163000 Nationwide Building Society Nationwide Building Society, 3-4, Bath Street, Bath, BA1 1SA 112000 The Eastern Eye Ltd 1st & 2nd Floors, 8a, Quiet Street, Bath, BA1 2JU 32500 Messers A Jones & Sons Ltd 19, Cheap Street, Bath, BA1 1NA 66000 Bath & N E Somerset Council 12, Charlotte Street, Bath, BA1 2NE 41250 Carr & Angier Levels 6 & Part 7, The Old Malthouse, Clarence Street, Bath, BA1 5NS 30500 Butcombe Brewery Ltd Old Crown (The), Kelston, Bath, BA1 9AQ 33000 Shaws (Cardiff) Ltd 19, Westgate Street, Bath, BA1 1EQ 50000 Lifestyle Pharmacy Ltd 14, New Bond Street, Bath, BA1 1BE 84000 Bath Rugby Ltd Club And Prems, Bath Rfc, Pulteney Mews, Bath, BA2 4DS 110000 West Of England Language Services Ltd International House Language S, 5, Trim Street, Bath, BA1 1HB 43250 O'Hara & Wood 29, Gay Street, Bath, BA1 2PD 33250 Wellsway (Bath) Ltd Wellsway B.M.W., Lower Bristol Road, Bath, BA2 3DR 131000 Bath & N E Somerset Council Lewis House, Manvers Street, Bath, BA1 1JH 252500 Abbey National Bldg Society Abbey National Bldg Society, 5a-6, Bath Street, Bath, BA1 1SA 84000 Paradise House Hotel, 86-88, Holloway, Bath, BA2 4PS 42000 12, Upper Borough Walls, Bath, BA1 1RH 35750 Moss Electrical Ltd 45-46 St James Parade, Lower Borough Walls, Bath, BA1 1UQ 49000 Claire Accessories Uk Ltd 23, Stall Street, Bath, BA1 1QF 100000 Thorntons Plc 1st Floor -

05-December-2012 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tiers 2 & 5 and Sub Tiers Only) DATE: 05-December-2012 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under Tiers 2 & 5 of the Points-Based System. It shows the organisation's name (in alphabetical order), the tier(s) they are licensed for, and whether they are A-rated or B-rated against each sub-tier. A sponsor may be licensed under more than one tier, and may have different ratings for each tier. No. of Sponsors on Register Licensed under Tiers 2 and 5: 25,750 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier (aq) Limited Leeds West Yorkshire Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General ?What If! Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) @ Bangkok Cafe Newcastle upon Tyne Tyne and Wear Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General @ Home Accommodation Services Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 5TW (A rating) Creative & Sporting 1 Life London Limited London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1 Tech LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 100% HALAL MEAT STORES LTD BIRMINGHAM West Midlands Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000heads Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000mercis LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) 101 Thai Kitchen London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 101010 DIGITAL LTD NEWARK Page 1 of 1632 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 108 Medical Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 111PIX.Com Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 119 West st Ltd Glasgow Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 13 Artists Brighton Tier 5TW (A rating) Creative & Sporting 13 strides Middlesbrough Cleveland Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 145 Food & Leisure Northampton Northampton Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 15 Healthcare Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 156 London Road Ltd t/as Cake R us Sheffield S. -

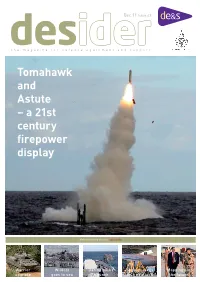

Tomahawk and Astute – a 21St Century Firepower Display

Dec 11 Issue 43 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Tomahawk and Astute – a 21st century firepower display Virtual warfare in focus See inside Warrior Wildcat Daring packs Support takes Mapping out upgrade goes to sea a punch on a new look the future FEATURES 6 24 Warfare staff go to war The Royal Navy has unveiled its new Maritime Composite Training System to a fanfare of trumpets and applause, marking the most radical change to its training for more than 40 years. 26 It’s the Army’s PlayStation generation Members of the British Army's PlayStation generation head to Helmand Province on the latest Operation Herrick deployment having honed their soldiering skills in virtual combat 28 Kestrel reaches full flight Project Kestrel – Information Systems and Services' reliable backbone communications network – is now complete, guaranteeing increased capacity and improved quality of communications in Afghanistan 2011 30 Defence Secretary praises ‘dedicated people’ New Defence Secretary Philip Hammond has praised 'the cover image most dedicated people in the public service' as he outlined A Tomahawk land attack missile is pictured being his vision for defence in his first public speech since fired byHMS Astute during her latest set of trials. The succeeding Dr Liam Fox missile, one of two fired on the trial, demonstrated complex evasive manoeuvres during flight and hit its designated target on a missile range DECEMBER desider NEWS Assistant Head, Public Relations: Ralph Dunn - 9352 30257 or 0117 9130257 5 Warrior in £1 billion -

Recommendations for Security and Safety Co-Engineering Merge ITEA2 Project # 11011

Template V 2.0 MERgE ITEA2 Project # 11011 ITEA2 – Project #11011 Multi-Concerns Interactions System Engineering 01.12.2012 to 31.03.2016 - Project Deliverable D3.4.4 – Part A (Stéphane Paul, TRT) Task 3.4 – Advanced concepts in safety and security co-engineering (Laurent RIOUX, TRT) WP3 – Advanced multi-concerns engineering concepts (Sam MICHIELS, KUL) Status [ ] Draft Document Created : 18.08.2015 [ ] To be reviewed Last edited : 22.04.2016 [X] Final Due date : 28.02.2016 Confidentiality [X] Public (for public distribution) Ready for review :01.02.2016 [ ] Restricted (only MERgE internal use) Document Version : 1.0 [ ] Confidential (only for individual partner(s)) Pages : 166 Contributors : TRT, ALL4TEC, ONERA, STUK Executive summary Nowadays, safety and security are two risk-driven activities that are tackled separately, giving rise to the indus- trial challenge of efficiently and economically co-engineering these two specialities. It is evident that there is a major opportunity to share on onomastics1, algorithms, (formal) methods and tools, in particular to reach higher levels of assurance at contained costs. Deliverable D3.4.4 is split in two parts. Part A (this document) is an extensive state of the art on safety and se- curity co-engineering of software intensive critical information systems. It essentially covers academic publica- tions and industry standards. Part B (companion document) first reports on two prototype tools dedicated to safety and security co- engineering. The first prototype was designed and developed by MERgE partners based on safety and security requirements from the MERgE software-defined radio test case. The document recalls the requirements and presents the high-level design. -

Requested Information.Pdf

Property Reference Current Rateable Number Full Property Address Occupants Business/Company name Value 10000600 6-7, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 30000 0010000800 8, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 44500 0010000911 9, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY Jody Cory Goldsmiths Ltd 20750 0010001000 10, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY Jim Garrahys Fudge Kitchen Ltd 21250 0010001300 13, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY 25000 0010001400 15 Cheap Street, 14, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY The National Trust 51000 0010500000 7, Abbey Churchyard, Bath, BA1 1LY Presto Retail Ltd 38250 0020000255 Gr & 1st Fl, 2, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 13000 0020000400 4, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 12500 0020000500 5, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW 28250 0020000800 8, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW At Sixes & Sevens Ltd 16250 0020000900 Mignon House, 9, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW Freshford Bazaar Ltd 16250 0020500000 The Crystal Palace, Abbey Green, Bath, BA1 1NW Marstons Plc 103000 00300001165 Hands Tearooms, 1, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN Hands Restaurant Ltd T/A Hands Cafe 21500 00300001175 1, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN Hands Restaurant Ltd 21750 0030000200 Elton House, 2, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN 24500 0030000400 4, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN Mirifice Ltd 31750 0030000500 The Landmark Trust, Elton House, Abbey Street, Bath, BA1 1NN The Landmark Trust 13250 0040000100 1, Abbeygate Street, Bath, BA1 1NP My Travel Uk Ltd T/A Going Places 39750 0040000200 The Golden Cot, 2, Abbeygate Street, Bath, BA1 1NP The Golden Cot 121000 0040000300 3, Abbeygate Street, Bath, -

Swordsman 29

The Worshipful Company of Engineers (Incorporated by Royal Charter 2004) The Swordsman Newsletter Issue 29, November 2012 The Swordsman Issue 29 CONTENTS Editorial 2 HM The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Luncheon, 5th June 2012 3 Visit To Bristol, 15th and 16th June 2012 4 Warden’s Lecture, 5th July 2012 5 Awards’ Dinner, 10th July 2012 14 Hawley Award Paper, Reducing Fuel Consumption in Light Commercial Vehicles by Christopher Vagg 24 Visit to JCB Academy and Factory, 17th July 2012 26 Annual Golf Day, 24th July 2012 27 Visit to Milton’s Cottage and Clivedon, 24th July 2012 29 Visit to the Hydraulic Accumulator and Limehouse Basin, 15th August 2012 29 Visit to the RNLI, Poole, 31st August and 1st September 2012 31 Out of Town Visit to Basel, Switzerland 20th to 23rd September 2012 33 Ladies’ Luncheon 3rd October 2012 45 Master’s Musings 46 Company News 47 Member’s News ` 49 COVER PHOTOGRAPHS Top Left Student Project Electric Car at JCB College Top Centre Sunset over Upton Lake from the RNLI College Top Right The RNLI Memorial in Poole Middle Left The Sails Bridge at Poole Closing Middle Centre The Compact Muon Solenoid Site on the Large Hadron Collider Middle Right The Rope Sculpture and Spiral Stair at the RNLI College Bottom From Left Not a Moon Lander but a Particle Detector, View over The Rhine in Basel, The Master at Cité de L’Automobile and The Town Hall in Basel Bottom Banner The CERN Logo FUTURE EVENTS 10th November 2012 Lord Mayors Show and Supper City and the Wharf 12th December 2012 Carol Service and Dinner Chapel Royal 11th January -

Nuclear Brief New Nuclear Power Will Help Drive Down the UK’S Carbon Emissions and Contribute to Ensuring a Secure Energy Future

The Magazine of the UK Nuclear Industry Association Civil Nuclear Industry Jobs Map 2010 Special Issue Nuclear Brief New nuclear power will help drive down the UK’s carbon emissions and contribute to ensuring a secure energy future. Story: Keith Parker, Chief Executive of the Nuclear Industry Association Nuclear power alone is not a silver bullet for the UK’s energy needs - the only true way to ensure we have Privately funded new nuclear will be crucial in helping the UK plentiful and affordable supplies of clean secure electricity meet our climate change obligations and securing energy supply is through a balanced energy mix - but that mix must maintain a substantial element of secure clean nuclear • The fuel for nuclear power stations is imported from stable energy at it’s heart. allied states such as Canada and Australia. We also have So why is nuclear so essential to the UK’s energy future? substantially in excess of 60 years of fuel for a nuclear fleet • Nuclear power has full lifecycle carbon emissions roughly already in the UK. This means that nuclear power is equal to those of wind power - making it a key strategically secure, not subject to sudden and devastating component of our low-carbon future. Our present nuclear supply interruptions. fleet - providing about 16% of UK electricity - prevents • Nuclear waste is well understood, it has been managed safely the release of around 40,000,000 tonnes of carbon every in the UK for some 60 years and we are making progress year in the UK. towards developing a final storage repository. -

Organismes Privés Agréés

LISTE DES ORGANISMES AGREES CLASSES PAR PAYS ET PAR SECTEURS D'ACTIVITES 22/02/2012 ALLEMAGNE Début Fin Siren Nom Sigle Activité RD CP Ville Téléphone Francfort - 2010 2011 ALTRAN GMBH Automatique 60313 ALLEMAGNE 2011 2013 EADS DEUTSCHLAND Automatique 81663 MUNICH 2009 2011 FLUITRONICS Automatique 47807 KREFELD STUTTGART - 2011 2013 FOXBORO ECKARDT Automatique D-70376 ALLEMAGNE BALINGEN - 2011 2013 IFK AUTOMATION IFK Automatique 72336 ALLEMAGNE DARMSTADT - 2011 2013 MAGNUM FUEL CELL AG MAGNUM Automatique 64293 ALLEMAGNE Birkenfeld - 2011 2013 STRATEC BIOMEDICAL SYSTEMS SBS Automatique 75217 Automatique, Electronique, ALLEMAGNE HARRO HOFLIGER Génie Electronique, ALLMERSBACH IM 2010 2012 71573 VERPACKUNGSMACHINEN Télécommunications, TAL - ALLEMAGNE Informatique, Optique FREIBURG- 2010 2012 ALDEVRON FREIBURG GMBH Biologie 79111 ALLEMAGNE LEIPZIG - 2011 2013 C-LECTA Biologie 04103 ALLEMAGNE Bayern - 2011 2013 EPILOGIC GMBH Biologie 85354 ALLEMAGNE NIEFERN- 2011 2013 EUROFINS GAB Biologie 75223 OSCHELBRONN - ALLEMAGNE Ebersberg - 2011 2013 EUROFINS MEDIGENOMICS Biologie 85560 ALLEMAGNE CONSTANCE - 2011 2013 GATC BIOTECH Biologie 78464 ALLEMAGNE REGENSHURG - 2010 2012 GENEART GA Biologie 93053 ALLEMAGNE ROBDORF- 2011 2013 HARLAN CYTOTEST CELL RESEARCH HARLAN CCR Biologie 64380 ALLEMAGNE INSTITUT FÜR BIOLOGISCHE ANALYTIK ROSSDORF - 2011 2013 IBACON Biologie 64380 UND CONSULTING ALLEMAGNE 2009 2011 MICROCOAT BIOTECHNOLOGIE Biologie 82347 BERNRIED 2009 2011 MIKROLAB Biologie 28259 BREMEN ALLEMAGNE Début Fin Siren Nom Sigle Activité RD CP Ville -

Altran Praxis

The Industrial Use of Formal Methods: Experiences of an Optimist Prof. Jonathan P. Bowen Museophile Limited, Oxford, UK London South Bank University www.jpbowen.com [email protected] Friday, 11 January 13 Experiences of an Optimist http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Redcliffe-Maud Friday, 11 January 13 Background: Safety and reliability Friday, 11 January 13 Background: Safety and reliability Friday, 11 January 13 Airbus A380 simulator Emirates Aviation College Dubai, 3 February 2011 Friday, 11 January 13 Theory and Practice “It has long been my personal view that the separation of practical and theoretical work is artificial and injurious. Much of the practical work done in computing, both in software and in hardware design, is unsound and clumsy because the people who do it have not any clear understanding of the fundamental design principles of their work. Most of the abstract mathematical and theoretical work is sterile because it has no point of contact with real computing.” — Christopher Strachey (1916–1975) Friday, 11 January 13 Formal Methods Friday, 11 January 13 Formal Methods • Term established by late 1970s – Next stage from structured design – Mathematical basis Friday, 11 January 13 Formal Methods • Term established by late 1970s – Next stage from structured design – Mathematical basis • Formal specification and (optionally) proof: – Validation (correct specification) – Verification (correct implementation wrt spec) Friday, 11 January 13 Formal Methods • Term established by late 1970s – Next stage from structured -

Nuclear Brief As an Industry We Have a Huge Amount of Work to Do in Engaging with Government and the General Public Following on from the Events in Japan

The Magazine of the UK Nuclear Industry Association Civil Nuclear Industry Jobs Map 2011 Special Issue Nuclear Brief As an industry we have a huge amount of work to do in engaging with Government and the general public following on from the events in Japan. In fact it is of utmost importance. We fully recognise that we have much to do – that we must present our case in a robust and transparent manner, while clearly making the case for new nuclear power stations to be built in the UK. Overview - by John Hutton, Chairman, NIA Dr Mike Weightman speaking at Fukushima The Japanese Earthquake and Tsunami are tragedies of still argue the case as before because it is a sound argument. But historic proportions. We know that Governments around the we must take into account public disquiet world have responded magnificently in coming to Japan’s aid. It is a major humanitarian disaster which many people As I have said before, the question is “Is it safe for us to go on seem to forget – caused by a natural disaster the like of building nuclear power stations?” And once again, I say the which we have not seen before. answer is an emphatic “yes”. It has been fascinating to see the key independent institutions like the G8’s Nuclear Energy Agency Some 15,000 people are confirmed dead. We must not lose or the IAEA move forward recommendations on lessons learned sight of Japan’s suffering. But to some this story is from Japan. This should give confidence to the public.