University of Oklahoma Graduate College a Mixed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMANCHE COUNTY Oklahoma

COMANCHE COUNTY Oklahoma COMMUNITY HEALTH ASSESSMENT Initial Release December 2016 . Revised September 2017 Contents Section One Community Contributors 1 Introduction 2 Mobilizing for Action Through Planning and Partnerships MAPP 3 Section Two Community Description and Demographics 4 Mortality and Leading Causes of Deaths 5 Social Determinants of Health 5 Education, and Income 6 Section Three MAPP Assessments: Community Health Status 7 Community Themes and Strengths 8 Forces of Change 9 Local Public Health System 11 Section Four Five Priority Elements Mental Health 12 Poverty 13 Obesity 14 Violence and Crime 15 Substance Abuse (Tobacco, Alcohol, Drugs) 16 Next Steps 17 Resources References Cited Works R1 Appendix A Comanche County Demographics, US Census Bureau A1 Appendix B Comanche County State of the County Report B1 Appendix C 2014 State of the State’s Health, page 66 C1 Appendix D County Health Ranking and Roadmaps D1 Appendix E Kids Count Report E1 Appendix F Comanche County Community Themes and Strengths Survey Results F1 Appendix G Comanche County Forces of Change Survey Results G1 Appendix H Comanche County Local Public Health System Results H1 Appendix I Comanche County Asset Mapping I1 CHA Updated September 2017 Contents Continued Resources Added – Revised September 2017 Appendix J 500 Cities Project J1 Appendix K Comanche County State of the County Health Report K1 Appendix L Lawton Consolidation Plan L1 Appendix M Lawton Consolidation Plan Aerial View M1 CHA Updated September 2017 Comanche County Community Health Assessment Section 1—page 1 Community Contributors A special thank you to all the Community Contributors who volunteer their time and energy. -

Lawton Public Schools Board of Education Regular Meeting March 12, 2019 5:00 PM Shoemaker Center Auditorium 753 NW Fort Sill Blvd Lawton, Oklahoma 73507

Lawton Public Schools Board of Education Regular Meeting March 12, 2019 5:00 PM Shoemaker Center Auditorium 753 NW Fort Sill Blvd Lawton, Oklahoma 73507 AGENDA The Board reserves the right to consider, take up and take action on any agenda item in any order, except as to items 1-3. The Board may discuss, make motions, and vote on all matters appearing on the agenda. Such vote may be to adopt, reject, table, reaffirm, rescind, or to take no action on any item. Any person with a disability who needs special accommodations to attend the Board of Education meeting should notify the Clerk of the Board at least 24 hours, to the extent possible, prior to the scheduled time of the Board meeting. The telephone number is 580-357- 6900. At the time and place designated, the Board will consider and act upon the matters set out on the Agenda for this meeting as follows: 1. Call to Order 2. Pledge of Allegiance - Tom Deighan 3. Roll Call 4. Special Guests/Special Recognition - Tom Deighan and Kent Jester a. MacArthur Middle School - Goal Setting 5. Architect and Construction Manager at Risk Update 6. Departmental Reports a. Information Item: Update - Business Operations and Educational Services Reports b. Information Item: Presentation to Board of Education relating to "BIg Rock" of Academic Excellence. 1. Information Item: Presentation of 2019 A-F Report Card School Ratings 2. Information Item: Presentation of Academic and Personnel Information related to University of Virginia Partners for Leadership in Education 7. Report of the Superintendent a. Information Item: District-Wide Needs Assessment Process (As a result of meetings with Site Leadership Teams, completed in January) b. -

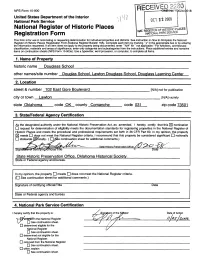

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determination for Individual Properties and Districts

N PS Form 10-900 -~eMB~N0rTD024-C 018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property__________________________________________ historic name Douqiass School__________________________________ other names/site number Douglas School. Lawton Douqiass School. Doualass Learning Center 2. Location_______________________________________________ street & number 102 East Gore Boulevard____________ [N/A] not for publication city or town Lawton_________________________________ [N/A] vicinity state Oklahoma___ code OK county Comanche___ code 031 zip code 73501 3. State/Federal Agency Certification_______________________________ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [>3 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [x] meets d does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant O nationally O statewide ^locally. -

Lawton Senior High School

LAWTON SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL ENROLLMENT BULLETIN 2018 - 2019 1 Introducing MYAP (Multi-Year Academic Planning) You now have an opportunity to plan your path to graduation through your Portal account. Using your Student or Parent Portal account, you will now have access to your Academic Planner and will be able to submit your course requests electronically. Please use the following instructions to submit your course requests for the upcoming school year: Log in to your Student Portal 1) account 2) Select Academic Planner 3) Click Next (right side of screen) You will now see a Planner screen listing columns of all four years of high school with courses grouped by subject area. Find the column for the grade level for the next school 4) year 5) Click in the "Type to search or select courses" box and select your course choice Repeat step 5 for each subject area (divided by dark 6) gray bar) **** If credits have been satisfied in any subject area, you do not need to make a selection within that area. 7) Under Alternates choose no more than 3 courses that you would like to take if your 1st choices are not available When you have completed all subject areas scroll to the top of 8) screen and click Save 1 If you do not have access to a computer or need assistance in the pre-enrollment process, please contact your school counselor. LAWTON HIGH SCHOOL HOME OF CHAMPIONS SCHOOL & COMMUNITY The Lawton-Fort Sill community has a population of 97,017 as of 2014. Lawton High School serves the educational needs of Lawton’s central and midtown areas as well as Fort Sill Army Post. -

Fort Sill Cial Media Presence Has Community

2 LAWTON PROUD 2019 Sunday, June 23, 2019 What is Lawton Proud? communications Lawton Proud is an im- progress of the Lawton/Fort age campaign designed to Sill community. In a short promote the positive prog- time, the Lawton Proud so- ress of the Lawton/Fort Sill cial media presence has community. The positive expanded due in part to the initiative highlights areas of success of the bi-weekly our community to include events calendar video up- but not limited to recreation date called, the Lawton & tourism, community ser- Lineup. Each showing of- vice projects, volunteerism, fers residents an opportu- and economic develop- nity to share their event to ment. the masses and continue to promote positive activi- OK-LIC# 1427 The Lawton Proud cam- ties in the community. paign, supported by the Lawton/Fort Sill Chamber By highlighting the posi- OK-LIC#1427 of Commerce, is com- tive accomplishments and prised of a volunteer based growth within the Lawton/ The Perkins Family have been PROUDLY Servicing businesses since 1981. committee packed with Fort Sill community, it has Business Phone Systems • Voice Mail • VOIP • Audio/Video business professionals, enhanced the overall im- Computer Network Cabling • Fiber Optics • Surveillance-CCTV and community leaders ea- age of the city as a great For all your business communication needs Contact: Jack or Troy Perkins (580) 355-0156 • 1007 SW F ger to promote the positive place to eat, work and play! Sunday, June 23, 2019 LAWTON PROUD 2019 3 3 R Packag NOW ONL $169900 LARGEST SELECTION LOWEST PRICES Pictures are for illustration purposes only. -

Lawton Public Schools 753 Fort Sill Blvd Lawton, Oklahoma 73507

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REGION VII OFFICE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS KANSAS MISSOURI ONE PETTICOAT LANE NEBRASKA 1010 WALNUT STREET, SUITE 320 OKLAHOMA SOUTH DAKOTA KANSAS CITY, MO 64106 March 29, 2018 SENT VIA EMAIL Dr. Tom Deighan, Superintendent Lawton Public Schools 753 Fort Sill Blvd Lawton, Oklahoma 73507 Re: Lawton Public Schools OCR Case Number: 07-18-1012 Dear Dr. Deighan, On October 12, 2017, the U.S. Department of Education (Department), Office for Civil Rights (OCR), received a complaint against Lawton Public Schools, Lawton, Oklahoma. This letter is to confirm the District has voluntarily submitted a Resolution Agreement (Agreement) to resolve this complaint. OCR investigated whether the District failed to educate students with disabilities assigned to self-contained classrooms in their least restrictive environments to the maximum extent possible for specials, recess, and lunch, in violation of the regulation implementing Section 504 at 34 C.F.R. § 104.34(a) and (b). OCR is responsible for enforcing: • Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504), 29 United States Code (U.S.C.) § 794, and its implementing regulation, 34 Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) Part 104. Section 504 prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability by recipients of Federal financial assistance. • Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (Title II), 42 U.S.C. § 12131, and its implementing regulation, 28 C.F.R. Part 35. Title II prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability by public entities. As a recipient of FFA from the Department, the District is subject to Section 504 and Title II. -

Transition Times an Oklahoma Transition Council Publication

Transition times An Oklahoma Transition council publication As April is in full force and summer is just around the corner, we all start to dream of lazy days sitting by the pool, resting up for the next school year to begin in Au- April 2013 gust! Don’t rest yet though! We still have a few more weeks to go before the end of the school year. There’s a ton of things for us all to do before we can kick In this Issue back lazily. We know you have to pack up your classroom for the summer, com- plete exit IEPs, help students update their resumes, and complete end-of-the- What worked this year?....…...p1 year paperwork! It’s important not to forget about your transition team in those Summer Camps……............p2-3 end-of-the-year processes! Having one last transition planning meeting with your transition team will allow for thoughts about what worked for your team this past Lawton 18-21 Program………p4 year and what didn’t work. One way of helping your team organize its thoughts about the school year is to ask yourself “what worked” and “what didn’t work.” Guide to Comm. Services……p5 Here’s one way it could look. Transition Handbook…...........p5 Identify the What worked What didn’t Upcoming Events……………..p5 event or with the event? work with the meeting. Brain + Child Conference……p6 event? Team Updates………………...p6 OTI 2012 Good planning session—excited Not everyone on the team could DRS Update…………..……….p7 Team about the events planned, etc.. -

Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the STATE BOARD of EDUCATION LAWTON PUBLIC

Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION LAWTON PUBLIC SCHOOLS DISTRICT LAWTON HIGH SCHOOL CAFETERIA 601 NW FORT SILL BOULEVARD LAWTON, OKLAHOMA July 28, 2016 The State Board of Education met in regular session at 1:35 p.m. on Thursday, July 28, 2016, in the Lawton High School Cafeteria at 601 NW Fort Sill Boulevard, Lawton, Oklahoma. The final agenda was posted at 12:30 p.m. on Wednesday, July 27, 2016 by Schyla Wright, Administrative Assistant at Lawton Public Schools. The following were present: Ms. Terrie Cheadle, Chief Executive Secretary Mr. Brad Clark, General Counsel Members of the State Board of Education present: State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister, Chairperson of the Board MG (R) Lee Baxter, Lawton Ms. Cathryn Franks, Roosevelt Mr. William “Bill” Flanagan, Claremore Mr. William “Bill” Price, Oklahoma City Mr. Robert J. Ross, Oklahoma City Members of the State Board of Education not present: Mr. Daniel Keating, Tulsa Others in attendance are shown as an attachment. Minutes of the Meeting of the State Board of Education July 28, 2016 CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister called the State Board of Education regular meeting to order at 1:35 p.m. and welcomed everyone to the meeting. Ms. Cheadle called the roll and ascertained there was a quorum. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE, OKLAHOMA FLAG SALUTE, AND MOMENT OF SILENCE Superintendent Hofmeister led Board Members and all present in the Pledge of Allegiance to the American Flag, a salute to the Oklahoma Flag, and a moment of silence. STATE SUPERINTENDENT Information from the State Superintendent Superintendent Hofmeister said it was wonderful to be in the City of Lawton and bringing the State Board of Education (SBE) on the road and EngageOK conference to Lawton High School. -

Lawton Public Schools Page 2

LAWTON PUBLIC SCHOOL S PO Box 1009 753 NW Fort Sill Blvd. Lawton OK 73502 580- 3 5 7 - 6 9 0 0 http://www.lawtonps.org/ SCHOOL/COMMUNITY CHA RACTERISTICS SCHOOLS Student/teacher ratio 15:1 EISENHOWER HS 2 Total Enrollment 14,747 LAWTON HIGH 3 Elementary (Pre-K—5th) 7,202 (17 Elementary Schools) MACARTHUR HS 4 Middle School (6th-8th) 3,091 (4 Middle Schools) MIDDLE SCHOOLS 5 High School (9th-12th) 4,107 ELEMENTARY 6 (3 High Schools) SCHOOLS 22% of students are Unformed Military Dependents Four Guiding Principles 1. Prepare Career Bound Citizens PERFORMANCE MEASURES Lawton Oklahoma 2. Shared Professional Ideals Students identified as Gifted/Talented 8.2% 14.2% 3. Communication, Collaboration & 1st-3rd Graders Receiving Reading Remediation 53.0% 39.0% Transparency Students in Special Education 18.0% 15.5% 4. Healthy & Fit Lifestyles Students as English Language Learners 4.1% 7.2% OKLAHOMA GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS — 2 3 C R E D ITS Subject Requirement (grades 9-12) State Academic Tests Language Arts 4 Units including English I, II, III, IV or other English course (including AP English courses) approved for college admission 10th grade students are tested in the following areas: Mathematics 3 units including Algebra I, Algebra II, Geometry, Trigonometry, Math Analysis, Calculus, AP math courses or any math course with content and/or rigor English Language Arts above Algebra I and approved for college admission. Mathematics Laboratory Science 3 units including Biology, Chemistry, Physics or other Lab Science course with content and/or rigor -

AUGUST 27, 2015 Minutes APPROVED

Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION LAWTON PUBLIC SCHOOLS SHOEMAKER EVENT CENTER AUDITORIUM 753 FORT SILL BOULEVARD LAWTON, OKLAHOMA August 27, 2015 The State Board of Education met in regular session at 1:05 p.m. on Thursday, August 27, 2015, in the Auditorium of the Lawton Public Schools-Shoemaker Education Center, 753 Fort Sill Boulevard, Lawton, Oklahoma. The final agenda was posted at 12:00 p.m. on Wednesday, August 26, 2015, by Keith Mitchell, Executive Director Communications, Lawton Public Schools. The following were present: Ms. Terrie Cheadle, Chief Executive Secretary Members of the State Board of Education present: State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister, Chairperson of the Board MG (R) Lee Baxter, Lawton Mr. Daniel Keating, Tulsa Mr. William “Bill” Price, Oklahoma City Mr. Robert J. Ross, Oklahoma City Mr. William E. “Bill” Flanagan, Claremore Members of the State Board of Education not present: Ms. Cathryn Franks, Roosevelt Others in attendance are shown as an attachment. 1 CALL TO ORDER AND ROLL CALL State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister called the State Board of Education regular meeting to order at 1:05 p.m. and welcomed everyone to the meeting. Ms. Cheadle called the roll and ascertained there was a quorum. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE, OKLAHOMA FLAG SALUTE, AND MOMENT OF SILENCE Superintendent Hofmeister led Board Members and all present in the Pledge of Allegiance to the American Flag, a salute to the Oklahoma Flag, and a moment of silence. STATE SUPERINTENDENT Information from the State Superintendent Prior to the meeting Superintendent Hofmeister introduced and swore in Mr. -

Type Your Name Here

Jennifer Dennis, Ph.D. Cameron University • 2800 West Gore Boulevard • Lawton, OK • 580-581-2515• [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, Education Administration Curriculum and Supervision, May, 2005 M.Ed. Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Weatherford, OK Secondary School Counseling, May, 1997 B.A. Cameron University, Lawton, OK, History, May, 1994 CERTIFICATIONS . Superintendent . Secondary Principal . Secondary Counselor . Language Arts Middle School . American History . Economics . Geography . Oklahoma History . Sociology/Anthropology . U.S. Government . World History PROFESSIONAL . Department Chair, Education Department, 2009 – present EXPERIENCE Cameron University . Associate Professor, Education Department 2011-present Cameron University . Assistant Professor, Education Department, 2005-2011 Cameron University . School Counselor, Lawton Public Schools 1997-2005 . Seventh Grade Geography Teacher, Lawton 1995-1997 Public Schools TEACHING/ . Department Chair 2009-present ADMINISTRATIVE . Associate Professor 2011-present ASSIGNMENTS . Assistant Professor 2005-2011 . Internship in the Jr./Sr. High School 2006-present . Advanced Foundations of Secondary Education 2007-present . Internship in School Administration 2007-present . Practicum in Teaching and Learning 2007-present . University Life for PLUS Students 2009-2010 Jennifer Dennis, Ph.D. Page 2 . Advanced Methods of Teaching Secondary 2007-2009 . Supervision of Curriculum and Instruction 2006-2009 . Community and School Relations 2005-07, 2016 . Master of Arts in Teaching Coordinator 2005-2007 . The Secondary Learner 2005-2007 . Teaching in the Secondary School 2005-2007 . Internship Seminar 2005-2007 PUBLICATIONS Article . Dennis, J.J. & O’Hair, M.J. (2010). Overcoming obstacles in using authentic instruction: A comparative case study of math and science teachers. American Secondary Education 38 (2), 4-22. Book Review . Dennis, J.J. (2008). -

Lawton Public Schools| 2021–2022 High School Course Catalog 1 Table of Contents

Lawton Public Schools| 2021–2022 High School Course Catalog 1 Table of Contents Letter from the Superintendent 3 General Information 4 Grading Scale 5 Graduation Requirements 6 Entrance Requirements for Oklahoma Colleges and Universities 7 College Student-Athlete Requirements 8 Oklahoma Promise 9 Testing Information 11 Concurrent Enrollment 12 Great Plains Technology Center 14 Individual Career & Academic Plan (ICAP) 17 Multi-Year Academic Plan 18 MYAP – Multi-Year Academic Planning 20 Course Descriptions 19 English / Language Arts 19 Math 22 Science 25 Social Studies 29 Business & Technology 33 Project Lead the Way (CareerTech) 35 Fine Arts 36 World Languages 41 General Electives 43 Special Education 52 Parental Curriculum Choice Letter 53 Websites for Post Secondary Planning 54 Clubs and Organizations 55 Course Index 54 Course Request 57 Lawton Public Schools is committed to developing programs and courses operated in conformity with all Federal and State laws pro- hibiting discrimination based on race, color, national origin, disability, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or military status . 2 Lawton Public Schools | 2021–2022 High School Course Catalog High Schools Eisenhower High School Lawton High School MacArthur High School Principal: LISA MARTINEZ Principal: CHARLOTTE OATES Principal: LAURA PUCCINO 5202 WEST GORE BLVD. 601 NW FT. SILL BLVD 4400 E. GORE BLVD LAWTON, OKLAHOMA OK 73505 LAWTON, OKLAHOMA OK 73507 LAWTON, OKLAHOMA OK 73501 PHONE: 580-355-9144 PHONE: 580-355-5170 PHONE: 580-355-5230 View EHS Website View LHS Website