Ostrich 82(2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

11 Fall Unamagazine

FALL 2011 • VOLUME 19 • No. 3 FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH ALABAMA Cover Story 10 ..... Thanks a Million, Harvey Robbins Features 3 ..... The Transition 14 ..... From Zero to Infinity 16 ..... Something Special 20 ..... The Sounds of the Pride 28 ..... Southern Laughs 30 ..... Academic Affairs Awards 33 ..... Excellence in Teaching Award 34 ..... China 38 ..... Words on the Breeze Departments 2 ..... President’s Message 6 ..... Around the Campus 45 ..... Class Notes 47 ..... In Memory FALL 2011 • VOLUME 19 • No. 3 for alumni and friends of the University of North Alabama president’s message ADMINISTRATION William G. Cale, Jr. President William G. Cale, Jr. The annual everyone to attend one of these. You may Vice President for Academic Affairs/Provost Handy festival contact Dr. Alan Medders (Vice President John Thornell is drawing large for Advancement, [email protected]) Vice President for Business and Financial Affairs crowds to the many or Mr. Mark Linder (Director of Athletics, Steve Smith venues where music [email protected]) for information or to Vice President for Student Affairs is being played. At arrange a meeting for your group. David Shields this time of year Sometimes we measure success by Vice President for University Advancement William G. Cale, Jr. it is impossible the things we can see, like a new building. Alan Medders to go anywhere More often, though, success happens one Vice Provost for International Affairs in town and not hear music. The festival student at a time as we provide more and Chunsheng Zhang is also a reminder that we are less than better educational opportunities. -

Widespread Crater-Related Pitted Materials on Mars: Further Evidence for the Role of Target Volatiles During the Impact Process ⇑ Livio L

Icarus 220 (2012) 348–368 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Widespread crater-related pitted materials on Mars: Further evidence for the role of target volatiles during the impact process ⇑ Livio L. Tornabene a, , Gordon R. Osinski a, Alfred S. McEwen b, Joseph M. Boyce c, Veronica J. Bray b, Christy M. Caudill b, John A. Grant d, Christopher W. Hamilton e, Sarah Mattson b, Peter J. Mouginis-Mark c a University of Western Ontario, Centre for Planetary Science and Exploration, Earth Sciences, London, ON, Canada N6A 5B7 b University of Arizona, Lunar and Planetary Lab, Tucson, AZ 85721-0092, USA c University of Hawai’i, Hawai’i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, Ma¯noa, HI 96822, USA d Smithsonian Institution, Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA e NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA article info abstract Article history: Recently acquired high-resolution images of martian impact craters provide further evidence for the Received 28 August 2011 interaction between subsurface volatiles and the impact cratering process. A densely pitted crater-related Revised 29 April 2012 unit has been identified in images of 204 craters from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. This sample of Accepted 9 May 2012 craters are nearly equally distributed between the two hemispheres, spanning from 53°Sto62°N latitude. Available online 24 May 2012 They range in diameter from 1 to 150 km, and are found at elevations between À5.5 to +5.2 km relative to the martian datum. The pits are polygonal to quasi-circular depressions that often occur in dense clus- Keywords: ters and range in size from 10 m to as large as 3 km. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Martian Subsurface Properties and Crater Formation Processes Inferred from Fresh Impact Crater Geometries

Martian Subsurface Properties and Crater Formation Processes Inferred From Fresh Impact Crater Geometries The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Stewart, Sarah T., and Gregory J. Valiant. 2006. Martian subsurface properties and crater formation processes inferred from fresh impact crater geometries. Meteoritics and Planetary Sciences 41: 1509-1537. Published Version http://meteoritics.org/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4727301 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Meteoritics & Planetary Science 41, Nr 10, 1509–1537 (2006) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Martian subsurface properties and crater formation processes inferred from fresh impact crater geometries Sarah T. STEWART* and Gregory J. VALIANT Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, 20 Oxford Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 22 October 2005; revision accepted 30 June 2006) Abstract–The geometry of simple impact craters reflects the properties of the target materials, and the diverse range of fluidized morphologies observed in Martian ejecta blankets are controlled by the near-surface composition and the climate at the time of impact. Using the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) data set, quantitative information about the strength of the upper crust and the dynamics of Martian ejecta blankets may be derived from crater geometry measurements. -

First Year of Coordinated Science Observations by Mars Express and Exomars 2016 Trace Gas Orbiter

MANUSCRIPT PRE-PRINT Icarus Special Issue “From Mars Express to ExoMars” https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.113707 First year of coordinated science observations by Mars Express and ExoMars 2016 Trace Gas Orbiter A. Cardesín-Moinelo1, B. Geiger1, G. Lacombe2, B. Ristic3, M. Costa1, D. Titov4, H. Svedhem4, J. Marín-Yaseli1, D. Merritt1, P. Martin1, M.A. López-Valverde5, P. Wolkenberg6, B. Gondet7 and Mars Express and ExoMars 2016 Science Ground Segment teams 1 European Space Astronomy Centre, Madrid, Spain 2 Laboratoire Atmosphères, Milieux, Observations Spatiales, Guyancourt, France 3 Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy, Brussels, Belgium 4 European Space Research and Technology Centre, Noordwijk, The Netherlands 5 Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía, Granada, Spain 6 Istituto Nazionale Astrofisica, Roma, Italy 7 Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale, Orsay, Paris, France Abstract Two spacecraft launched and operated by the European Space Agency are currently performing observations in Mars orbit. For more than 15 years Mars Express has been conducting global surveys of the surface, the atmosphere and the plasma environment of the Red Planet. The Trace Gas Orbiter, the first element of the ExoMars programme, began its science phase in 2018 focusing on investigations of the atmospheric composition with unprecedented sensitivity as well as surface and subsurface studies. The coordination of observation programmes of both spacecraft aims at cross calibration of the instruments and exploitation of new opportunities provided by the presence of two spacecraft whose science operations are performed by two closely collaborating teams at the European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC). In this paper we describe the first combined observations executed by the Mars Express and Trace Gas Orbiter missions since the start of the TGO operational phase in April 2018 until June 2019. -

Multi-Page.Pdf

Public Disclosure Authorized _______ ;- _____ ____ - -. '-ujuLuzmmw---- Public Disclosure Authorized __________~~~ It lif't5.> fL Elf-iWEtfWIi5I------ S -~ __~_, ~ S,, _ 3111£'' ! - !'_= Public Disclosure Authorized al~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~sl .' _1EIf l i . i.5I!... ..IillWM .,,= aN N B 1. , l h~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized = r =s s s ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~foss XIe l l=4 1lill'%WYldii.Ul~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ itA=iII1 l~w 6t*t Estimating Woody Biomass in Sub-Saharan Africa Estimating Woody Biomass in Sub-Saharan Africa Andrew C. Miflington Richard W. Critdhley Terry D. Douglas Paul Ryan With contributions by Roger Bevan John Kirkby Phil O'Keefe Ian Ryle The World Bank Washington, D.C. @1994 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433, US.A. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing March 1994 The findings, interpretations, and conclusiornsexpressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and policies of the World Bank or its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent Some sources cited in this paper may be informal documents that are not readily available. The manLerialin this publication is copyrighted. Requests for permission to reproduce portions of it should be sent to the Office of the Publisher at the address shown in the copyright notice above. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally give permission promptly and, when the reproduction is for noncommnercial purposes, without asking a fee. Permission to copy portions for classroom use is granted through the CopyrightClearance Center, Inc-, Suite 910,222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, Massachusetts 01923, US.A. -

Workshop on Mars Telescopic Observations

WORKSHCPON MARS TELESCOPIC OBSERVATIONS 90' 180'-;~~~~~~------------------..~~------------~~----..~o~,· 270' LPI Technical Report Number 95-04 Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 LPIITR--95-04 WORKSHOP ON MARS TELESCOPIC OBSERVATIONS Edited by J. F. Bell III and J. E. Moersch Held at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York August 14-15, 1995 Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 LPI Technical Report Number 95-04 LPIITR--95-04 Compiled in 1995 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under Contract No. NASW-4574 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this volume may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, education, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as the appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. This report may be cited as Bell J. F.III and Moersch J. E., eds. (1995) Workshop on Mars Telescopic Observations. LPI Tech. Rpt. 95-04, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 33 pp. This report is distributed by ORDER DEPARTMENT Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Mail order requestors will be invoiced for the cost ofshipping and handling. Cover: Orbits of Mars (outer ellipse) and Earth (inner ellipse) showing oppositions of the planet from 1954to 1999. From C. Aammarion (1954) The Flammarion Book ofAstronomy, Simon and Schuster, New York. LPl Technical Report 95-04 iii Introduction The Mars Telescopic Observations Workshop, held August 14-15, 1995, at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, was organized and planned with two primary goals in mind: The first goal was to facilitate discussions among and between amateur and professional observers and to create a workshop environment fostering collaborations and comparisons within the Mars ob serving community. -

In Pdf Format

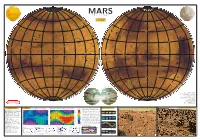

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

Simulating Martian Regolith in the Laboratory

ARTICLE IN PRESS Planetary and Space Science 56 (2008) 2009–2025 www.elsevier.com/locate/pss Simulating Martian regolith in the laboratory Karsten Seiferlina,Ã, Pascale Ehrenfreundb, James Garryb, Kurt Gundersona,E.Hu¨tterc, Gu¨nter Karglc, Alessandro Maturillid, Jonathan Peter Merrisone aPhysikalisches Institut, Universita¨t Bern, Sidlerstrasse 5, 3012 Bern, Switzerland bAstrobiology Laboratory, Leiden Institute of Chemistry, P.O. Box 9502, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands cInstitut fu¨r Weltraumforschung, Graz, O¨sterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Austria dGerman Aerospace Centre (DLR), Institute for Planetary Research, Rutherfordstr. 2, 12489 Berlin-Adlershof, Germany eAarhus Mars Simulation Laboratory, Aarhus University, Denmark Received 6 December 2007; received in revised form 21 July 2008; accepted 21 September 2008 Available online 15 October 2008 Abstract Regolith and dust cover the surfaces of the Solar Systems solid bodies, and thus constitute the visible surface of these objects. The topmost layers also interact with space or the atmosphere in the case of Mars, Venus and Titan. Surface probes have been proposed, studied and flown to some of these worlds. Landers and some of the mechanisms they carry, e.g. sampling devices, drills and subsurface probes (‘‘moles’’) will interact with the porous surface layer. The absence of true extraterrestrial test materials in ample quantities restricts experiments to the use of soil or regolith analogue materials. Several standardized soil simulants have been developed and produced and are commonly used for a variety of laboratory experiments. In this paper we intend to give an overview of some of the most important soil simulants, and describe experiments (penetrometry, thermal conductivity, aeolian transport, goniometry, spectroscopy and exobiology) made in various European laboratory facilities. -

Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Entomology

Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) A review of the Solenopsis genus-group and revision of Afrotropical Monomorium Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Barry Bolton Entomology series Vol 54 No 3 25 June 1987 The Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), instituted in 1949, is issued in four scientific series, Botany, Entomology, Geology (incorporating Mineralogy) and Zoology, and an Historical series. Papers in the Bulletin are primarily the results of research carried out on the unique and ever-growing collections of the Museum, both by the scientific staff of the Museum and by specialists from elsewhere who make use of the Museum's resources. Many of the papers are works of reference that will remain indispensable for years to come. Parts are published at irregular intervals as they become ready, each is complete in itself, available separately, and individually priced. Volumes contain about 300 pages and several volumes may appear within a calendar year. Subscriptions may be placed for one or more of the series on either an Annual or Per Volume basis. Prices vary according to the contents of the individual parts. Orders and enquiries should be sent to: Publications Sales, British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, England. World List abbreviation: Bull. Br. Mus. nat. Hist. (Ent.) ©British Museum (Natural History), 1987 The Entomology series is produced under the general editorship of the Keeper of Entomology: Laurence A. Mound Assistant Editor: W. Gerald Tremewan ISBN 565 06026 ISSN 0524-6431 Entomology -

Geologic Mapping of Vinogradov Crater on Mars: Ancient Phyllosilicates to Alluvial Fans

45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014) 2382.pdf GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF VINOGRADOV CRATER ON MARS: ANCIENT PHYLLOSILICATES TO ALLUVIAL FANS. S. A. Wilson1, J. A. Grant1, C. M. Weitz2 and R. P. Irwin1 1Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, 6th St. at Independence Ave. SW, Washington, DC, 20560 ([email protected]), 2Planetary Science Institute, 1700 E Fort Lowell, Suite 106, Tucson, AZ 85719. Introduction: Southern Margaritifer Terra on Mars preserves a long geologic history of water-related activity (Fig. 1). The northward-draining Uzboi– Ladon–Morava (ULM) outflow system dominates drainage in southwest Margaritifer Terra [1-4] and was incised during the Late Noachian to Hesperian [2]. Holden crater formed in the mid to Late Hesperian [5] and blocked the northern end of Uzboi, creating an enclosed basin that filled as a large paleolake [6]. The geology of Vinogradov crater and vicinity, located ~200 km west of Ladon basin and 250 km northwest of Holden crater (Fig. 1), is consistent with the long and diverse history of water in the region to the east [5]. Figure 2. Vinogradov crater is flanked by fan-bearing craters Roddy (D=85.8km; 21.7ºS, 320.6ºE), Gringauz (D=71.0km; 20.7ºS, 324.3ºE) and Luba (D=38.8km, 18.3ºS, 323ºE). Phyllosilicates are found in the depression (dashed line) between ejecta from Roddy and Gringauz (Fig. 3). MOLA 128 pixel/degree with 25 m contours over THEMIS daytime IR mosaic. Figure 1. Southern Margaritifer Terra indicating major place names. Stars show craters containing alluvial fans [7-8].