JONATHAN HARVEY List of Works BIOGRAPHY CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 124, 2004-2005

2004-2005 SEASON BOSTON SYM PHONY *J ORCHESTRA JAM ES LEVI N E ''"- ;* - JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK CONDUCTOR EMERITUS SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE Invite the entire string section for cocktails. With floor plans from 2,300 to over Phase One of this 5,000 square feet, you can entertain magnificent property is in grand style at Longyear. 100% sold and occupied. Enjoy 24-hour concierge service, Phase Two is now under con- single-floor condominium living struction and being offered by at its absolute finest, all Sotheby's International Realty & harmoniously located on Hammond Residential Real Estate an extraordinary eight- GMAC. Priced from $1,725,000. acre gated community atop prestigious Call Hammond at (617) 731-4644, Fisher Hill ext. 410. LONGYEAR. a/ l7isner jtfiff BROOKLINE V+* rm SOTHEBY'S Hammond CORTLAND IIIIIIUU] SHE- | h PROPERTIES INC ESTATE 3Bhd International Realty REASON #11 open heart surgery that's a lot less open There are lots of reasons to consider Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like minimally invasive heart surgery that minimizes pain, reduces cosmetic trauma and speeds recovery time. From cardiac services and gastroenterology to organ transplantation and cancer care, you'll find some of the most cutting-edge medical advances available anywhere. To find out more, visit www.bidmc.harvard.edu or call 800-667-5356. Beth Israel A teaching hospital of Deaconess Harvard Medical School Medical Center Red | the Boston Affiliated with Joslin Clinic | A Research Partner of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Official Hospital of James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 124th Season, 2004-2005 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Premium Blend: Middle School Percussion Curriculum Utilizing Western and Non-Western Pedagogy

Premium Blend: Middle School Percussion Curriculum Utilizing Western and Non-Western Pedagogy Bob Siemienkowicz Winfield School District 34 OS 150 Park Street Winfield, Illinois 60190 A Clinic/Demonstration Presented by Bob Siemienkowicz [email protected] And The 630.909.4974 Winfield Percussion Ensembles ACT 1 Good morning. Thank you for allowing us to show what we do and how we do it. Our program works for our situation in Winfield and we hope portions of it will work for your program. Let’s start with a song and then we will time warp into year one of our program. SONG – Prelude in E minor YEAR 1 – All those instruments The Winfield Band program, my philosophy has been that rhythm is the key to success. I tell all band students “You can learn the notes and fingerings fine, but without good rhythm, no one will understand what you are playing.” This is also true in folkloric music. Faster does not mean you are a better player. How well you communicate musically establishes your level of proficiency. Our first lessons with all band students are clapping exercises I design and lessons from the Goldenberg Percussion method book. Without the impedance of embouchure, fingerings and the thought of dropping a $500 instrument on the floor, the student becomes completely focused on rhythmic study. For the first percussion lesson, the focus is also rhythmic. Without the need for lips, we play hand percussion immediately. For the first Western rudiment, we play paradiddles on conga drums or bongos (PLAY HERE). All percussion students must say paradiddle while they play it. -

A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming Javier Diaz The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2966 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MEANING BEYOND WORDS: A MUSICAL ANALYSIS OF AFRO-CUBAN BATÁ DRUMMING by JAVIER DIAZ A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2019 2018 JAVIER DIAZ All rights reserved ii Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor in Musical Arts. ——————————— —————————————————— Date Benjamin Lapidus Chair of Examining Committee ——————————— —————————————————— Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Peter Manuel, Advisor Janette Tilley, First Reader David Font-Navarrete, Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Meaning Beyond Words: A Musical Analysis of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming by Javier Diaz Advisor: Peter Manuel This dissertation consists of a musical analysis of Afro-Cuban batá drumming. Current scholarship focuses on ethnographic research, descriptive analysis, transcriptions, and studies on the language encoding capabilities of batá. -

Dominic Muldowney

Update April 2019 Dominic Muldowney The Anatomy Lesson (1993) Sinfonietta/Dominic Muldowney violin and piano Score 0-571-56341-4 (fp) on sale, parts for hire 8 minutes Commissioned by Tasmin Little with funds from the John S Cohen Concerto for Trumpet (1993) Foundation trumpet and orchestra with click-track tape FP: 12.10.1993, Pasydy Theatre, South Nicosia, Cyprus: Tasmin Little/ 20 minutes Piers Lane 2.2.2.2(II=cbsn) – 2000 – perc(2): 4 wdbl/2 susp.cym/2 mar – pno – Piano score and part 0-571-51469-3 (fp) on sale strings (Elec requirements): pre-recorded click-track tape/7 earpieces for The Brontes Suite (1998) conductor, tpt solo, pno, 2 cls and 2 perc Commissioned by the Premiere Ensemble and South Bank Centre and orchestra supported by the Arts Council of Great Britain 12 minutes FP: 14.6.1993, Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, UK: John Wallace/ 1(=picc).1.2(II=bcl).2(II=cbsn) – 2100 – perc(1): SD/BD+ped/3 tpl.bl/ Premiere Ensemble/Mark Wigglesworth wdbl/bongos/tgl/mcas/cabaca/susp.cym/glsp – pno – strings Score, parts and click-track tape for hire FP: 9.3.1998, St John’s Smith Square, London, UK: Orchestra of St John’s Smith Square/John Lubbock Score and parts for hire Concerto for Violin (1989) violin, large orchestra, tape, two conductors and click- The Brontes (1995) track tape Ballet for orchestra 26 minutes 120 minutes 3(II+III=picc).2.3.2(=cbsn) – 4431 – perc(4): 4 wdbl/4 tpl.bl/4 1121 – 2110 – perc(2): claves/tom-t/2 tamb/BD/glsp/vib/tgl/susp.cym/ sandblock/2 claves/4 conga/2 cabaca/2 BD/2 tom-t/2 tam-t/2 mar/2 SD/cabassa/tam-t/xylo/congas/bongos/tpl.bl/mcas/3 wdbl – keyboard susp.cym/2 splash cym/2 tgl/2 drum kit(=hi-hat/SD/BD+foot ped)/2 – harp – strings mcas or chocalho – 2 harp – strings FP: 6.3.1995, Grand Theatre, Leeds, UK: Northern Ballet Theatre (Elec requirements): pre-recorded 4-track tape, 6 radio earpieces to Score and parts for hire the 2 conductors and 4 perc. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

Music You Know & Schubert

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, April 29, 2016, 8:00pm MUSIC YOU KNOW: STORYTELLING David Robertson, conductor Celeste Golden Boyer, violin BERNSTEIN Candide Overture (1956) (1918-1990) PONCHIELLI Dance of the Hours from La Gioconda (1876) (1834-1886) VITALI/ Chaconne in G minor for Violin and Orchestra (ca. 1705/1911) orch. Charlier (1663-1745) Celeste Golden Boyer, violin INTERMISSION HUMPERDINCK Prelude to Hänsel und Gretel (1893) (1854-1921) DUKAS The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1897) (1865-1935) STEFAN FREUND Cyrillic Dreams (2009) (b. 1974) David Halen, violin Alison Harney, violin Jonathan Chu, viola Daniel Lee, cello WAGNER/ Ride of the Valkyries from Die Walküre (1856) arr. Hutschenruyter (1813-1883) 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This concert is part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. This concert is part of the Whitaker Foundation Music You Know Series. This concert is supported by University College at Washington University. David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. The concert of Friday, April 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Andrew C. Taylor. The concert of Friday, April 29, is the Joanne and Joel Iskiwitch Concert. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of the Delmar Gardens Family and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 A FEW THINGS YOU MIGHT NOT KNOW ABOUT MUSIC YOU KNOW BY EDDIE SILVA For those of you who stayed up late to watch The Dick Cavett Show on TV, you may recognize Leonard Bernstein’s Candide Overture as the theme song played by the band led by Bobby Rosengarden. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Vagopoulou, Evaggelia Title: Cultural tradition and contemporary thought in Iannis Xenakis's vocal works General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Cultural Tradition and Contemporary Thought in lannis Xenakis's Vocal Works Volume I: Thesis Text Evaggelia Vagopoulou A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordancewith the degree requirements of the of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, Music Department. -

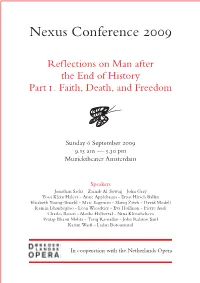

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 124, 2004-2005

2004-2005 SEASON BOSTON SYM PHONY ORCHESTRA JAMES LEVINE m *x 553 JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK CONDUCTOR EMERITUS SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE Invite the entire string section for cocktails. With floor plans from 2,300 to over Phase One of this 5,000 square feet, you can entertain magnificent property is in grand style at Longyear. 100% sold and occupied. Enjoy 24-hour concierge service, Phase Two is now under con- single-floor condominium living struction and being offered by at its absolute finest, all Sotheby's International Realty d harmoniously located on Hammond Residential Real Estate an extraordinary eight- GMAC Priced from $1,725,000. acre gated community atop prestigious Call Hammond at (617) 731-4644, Fisher Hill ext. 410. LONGYEAR a/ Jisner JH:ill BROOKLINE CORTLAND SOTHEBY'S Hammond PROPERTIES INC. International Realty REAL ESTATE m4WH "nfaBBOHnirAn11 Hfl Partners McLean Hospital is the largest psychiatric facility of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate HEALTHCARE of Massachusetts General Hospital and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #11 open heart surgery that's a lot less open There are lots of reasons to consider Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like minimally invasive heart surgery that minimizes pain, reduces cosmetic trauma and speeds recovery time. From cardiac services and gastroenterology to organ transplantation and cancer care, you'll find some of the most cutting-edge medical advances available anywhere. To find out more, visit www.bidmc.harvard.edu or call 800-667-5356. Israel A teaching hospital of Beth Deaconess Harvard Medical School Medical Center Affiliated Re with Joslin Clinic | A Research Partner of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center | Official Hospital of the Boston ^^^^^^^^^^^1 James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 124th Season, 2004-2005 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Nuit De La Percussion Solo N U It De La Percu Ssion / Solo

NUIT DE LA PERCUSSION SOLO Mercredi 29 Juin, 19h Le CENTQUATRE-PARIS, salle 400 Laurent Mariusse percussions Manuel Poletti (Ircam), Pierre-Adrien Théo (La Muse en Circuit), José Miguel Fernandez (Art Zoyd) réalisation informatique musicale JAMES WOOD Secret Dialogues CRÉATION FRANÇAISE LAURENT DURUPT 61 stèles [de pierre, de bois, de silence, de souffle…],commande de l’Ircam-Centre Pompidou CRÉATION TÔN-THÂT TIET Balade LAURENT MARIUSSE Naissance, commande de la Muse en Circuit CRÉATION NUIT DE LA PERCUSSION / SOLO LA PERCUSSION NUIT DE DANIEL D’ADAMO A Faraday Cage, commande d’Art Zoyd-CTCM et Cesaré-CNCM CRÉATION Laurent Mariusse improvisera commentaires et transitions entre les pièces. Durée : 1h environ Production Ircam-Centre Pompidou. Avec le soutien de la Sacem. L’Ircam est partenaire du CENTQUATRE-Paris pour l’accueil des projets d’expérimentation autour du spectacle vivant. Mercredi 29 Juin, 19h 29 Mercredi 400 salle CENTQUATRE-PARIS, Le | NUIT DE LA PERCUSSION / SOLO Entretien avec Laurent Mariusse La magie du marimba Laurent Mariusse, vous êtes à l’initiative de se complètent, se distinguant des autres pièces ce programme original autour du marimba de ce programme par un rapport au temps très cinq octaves : d’où vous est venue l’idée ? particulier. Laurent Mariusse : Tout est parti de la com - mande de Secret Dialogues, passée à James Pourquoi avoir jeté votre dévolu sur le marimba Wood par un consortium de marimbistes dont je cinq octaves ? Qu’est-ce qui fait à vos yeux la fais partie. Ce mode de commande est fréquent spécificité de cet instrument ? aux États-Unis : il en réduit le coût pour chaque La percussion est un instrument de notre époque. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec.