Front Matter Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moments in Time: Lithographs from the HWS Art Collection

IN TIME LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION PATRICIA MATHEWS KATHRYN VAUGHN ESSAYS BY: SARA GREENLEAF TIMOTHY STARR ‘08 DIANA HAYDOCK ‘09 ANNA WAGER ‘09 BARRY SAMAHA ‘10 EMILY SAROKIN ‘10 GRAPHIC DESIGN BY: ANNE WAKEMAN ‘09 PHOTOGRAPHY BY: LAUREN LONG HOBART & WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES 2009 MOMENTS IN TIME: LITHOGRAPHS FROM THE HWS ART COLLECTION HIS EXHIBITION IS THE FIRST IN A SERIES INTENDED TO HIGHLIGHT THE HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES ART COLLECTION. THE ART COLLECTION OF HOBART TAND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES IS FOUNDED ON THE BELIEF THAT THE STUDY AND APPRECIATION OF ORIGINAL WORKS OF ART IS AN INDISPENSABLE PART OF A LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION. IN LIGHT OF THIS EDUCATIONAL MISSION, WE OFFERED AN INTERNSHIP FOR ONE-HALF CREDIT TO STUDENTS OF HIGH STANDING TO RESEARCH AND WRITE THE CATALOGUE ENTRIES, UNDER OUR SUPERVISION, FOR EACH OBJECT IN THE EXHIBITION. THIS GAVE STUDENTS THE OPPORTUNITY TO LEARN MUSEUM PRACTICE AS WELL AS TO ADD A PUBLICATION FOR THEIR RÉSUMÉ. FOR THIS FIRST EXHIBITION, WE HAVE CHOSEN TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF THE MORE IMPORTANT ARTISTS IN OUR LARGE COLLECTION OF LITHOGRAPHS AS WELL AS TO HIGHLIGHT A PRINT MEDIUM THAT PLAYED AN INFLUENTIAL ROLE IN THE DEVELOPMENT AND DISSEMINATION OF MODERN ART. OUR PRINT COLLECTION IS THE RICHEST AREA OF THE HWS COLLECTION, AND THIS EXHIBITION GIVES US THE OPPORTUNITY TO HIGHLIGHT SOME OF OUR MAJOR CONTRIBUTORS. ROBERT NORTH HAS BEEN ESPECIALLY GENER- OUS. IN THIS SMALL EXHIBITION ALONE, HE HAS DONATED, AMONG OTHERS, WORKS OF THE WELL-KNOWN ARTISTS ROMARE BEARDEN, GEORGE BELLOWS OF WHICH WE HAVE TWELVE, AND THOMAS HART BENTON – THE GREAT REGIONALIST ARTIST AND TEACHER OF JACKSON POLLOCK. -

On Representation: Biology Politics

ON REPRESENTATION: BIOLOGY POLITICS Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art By Enma Saiz Low Residency MFA School of the Art Institute of Chicago Summer, 2020 Thesis Committee Advisor Corrine E. Fitzpatrick, Lecturer, SAIC #2 of #30 Abstract! In this thesis I write letters in an epistolary style to four artists whose work has influenced my own visual arts practice—Ana Mendieta, Doris Salcedo, Laura Aguilar, and Terri Kapsalis. The manner in which they represent the “other” in their oeuvres—respectfully, without repeating stereotypes, and sometimes elevating the “other” to ecstatic visions—has influenced my work which has to do with victims of medical experimentation, particularly African Americans and women.! Acknowledgements! A heartfelt thank you to Corrine Fitzpatrick, my writing advisor at SAIC who helped me pare down the writing to its most significant constituent parts, to Claire Pentecost, my visual arts advisor at SAIC who helped me clarify my thinking around significant concepts in the thesis, and to my son, Sam Yaziji, the emerging writer who so carefully helped me with word selection and grammar. Thank you to Marilyn Traeger for her phenomenal photography skills in shooting and editing the Torso series.! #3 of #30 On Representation: Biology Politics1 ! As a medical doctor I feel a duty to shed light on the violence and injustices su$ered by women and people of color at the hands of the medical establishment. By shedding light on these atrocities through my research-based visual arts practice, my desire is to help educate the public about the violence perpetrated against the victims of medical experimentation. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

Links (Urls) to Websites Referenced in This Document Were Accurate at the Time of Publication

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. INCLUSIVE STORIES Although scholars of LGBTQ history have generally been inclusive of women, the working classes, and gender-nonconforming people, the narrative that is found in mainstream media and that many people think of when they think of LGBTQ history is overwhelmingly white, middle-class, male, and has been focused on urban communities. While these are important histories, they do not present a full picture of LGBTQ history. To include other communities, we asked the authors to look beyond the more well-known stories. Inclusion within each chapter, however, isn’t enough to describe the geographic, economic, legal, and other cultural factors that shaped these diverse histories. Therefore, we commissioned chapters providing broad historical contexts for two spirit, transgender, Latino/a, African American Pacific Islander, and bisexual communities. -

Pop Culture and Art

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Visual Arts 6th Grade Unit Title: Pop Culture and Art INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Pueblo County School District Amie Holmberg Brenna Reedy Colorado State University Patrick Fahey, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Denver School District Capucine Chapman Fountain School District Sean Norman Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Visual Arts Grade Level 6th Grade Course Name/Course Code Sixth Grade Visual Arts Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Observe and Learn to 1. The characteristics and expressive features of art and design are used in unique ways to respond to two- and VA09-GR.6-S.1-GLE.1 Comprehend three-dimensional art 2. Art created across time and cultures can exhibit stylistic differences and commonalities VA09-GR.6-S.1-GLE.2 3. Specific art vocabulary is used to describe, analyze, and interpret works of art VA09-GR.6-S.1-GLE.3 2. Envision and Critique to 1. Visual symbols and metaphors can be used to create visual expression VA09-GR.6-S.2-GLE.1 Reflect 2. Key concepts, issues, and themes connect the visual arts to other disciplines such as the humanities, sciences, VA09-GR.6-S.2-GLE.1 mathematics, social studies, and technology 3. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 1 2 Annual Report 2005 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2005 www.mam.org 1 2 Annual Report 2005 Contents Board of Trustees . 4 Committees of the Board of Trustees . 4 President and Chairman’s Report . 6 Director’s Report . 9 Curatorial Report . 11 Exhibitions, Traveling Exhibitions . 14 Loans . 14 Acquisitions . 16 Publications . 35 Attendance . 36 Membership . 37 Education and Public Programs . 38 Year in Review . 39 Development . 43 Donors . 44 Support Groups . 51 Support Group Officers . 55 Staff . 58 Financial Report . 61 Financial Statements . 63 OPPOSITE: Ludwig Meidner, Self-Portrait (detail), 1912. See listing p. 16. PREVIOUS PAGE: Milwaukee Art Museum, Quadracci Pavilion designed by Santiago Calatrava as seen looking east down Wisconsin Avenue. www.mam.org 3 Board of Trustees As of August 30, 2005 BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEES OF Earlier European Arts Committee Jean Friedlander AND COMMITTEES THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jim Quirk Milton Gutglass George T. Jacobi MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair David Ritz Sheldon B. Lubar Sheldon B. Lubar Martha R. Bolles Helen Weber Chairman Chair Vice Chair and Secretary Barry Wind Andrew A. Ziegler Christopher S. Abele Barbara B. Buzard EDUCATION COMMITTEE President Donald W. Baumgartner Joanne Charlton Lori Bechthold Margaret S. Chester Christopher S. Abele Donald W. Baumgartner Frederic G. Friedman Stephen Einhorn Chair Vice President, Past President Terry A. Hueneke George A. Evans, Jr. Kim Abler Mary Ann LaBahn Eckhart Grohmann Frederic G. Friedman John Augenstein Marianne Lubar Frederick F. Hansen Assistant Secretary and James Barany P. M ichael Mahoney Avis M. Heller Legal Counsel José Chavez Betty Ewens Quadracci Arthur J. Laskin Terrence Coffman Mary Ann LaBahn James H. -

Creatinc Art: Media and Processes

3 Creating art: media and Processes ave you ever created a picture using chalk or charcoal? What kinds H of pictures have you taken with a camera? What do you think of when you have a piece of clay in your hands? An artist can choose from a great many different kinds of materials. The artist’s decision about which materials, or which medium, to use will have a dramatic impact on the appearance of the finished work. The different processes, or ways in which artists use that medium, can produce strikingly different results. Read to Find Out As you read this chapter, compare and contrast the materials and processes of works created in the same art form. Compare the two drawings on page 52. How are they the same? How are they different? Compare the two photographs on page 63. What is similar? What is different? Focus Activity Draw two overlapping circles to create a Venn dia- gram. Consider the works of art on page 66. Organize the information you wish to compare and contrast. List the traits unique to Tree of Life (Figure 3.1) in one circle and the traits unique to Madonna and Child (Figure 3.24) in the opposite circle. List the traits similar to both pieces in the space created by the overlapping circles. Both sculptures are made from clay, but each artist used the medium of clay and processes of sculpture in very different ways. Using the Time Line Take a look at some of the other artworks from this chapter that are introduced on the Time Line. -

Download File

EXPLORING LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN IN NEW YORK CITY MUSEUMS EXPLORING LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN IN NEW YORK CITY MUSEUMS Museums as a resource for K-12 teachers to infuse Latin American and Caribbean culture in the classroom The Institute of Latin American Studies (ILAS) K-12 Outreach Program has commissioned the production of this Museum Guide to serve as a resource for K-12 teachers, with the objective of encouraging and facilitating the use of museums in New York City to include Latin American history and culture in the classroom. The ILAS K-12 Outreach Program strives to enhance the professional capacity of teachers in a multicultural New York City (NYC) environment and promote the inclusion of Latin American and Caribbean history and culture in their classrooms and students’ daily lives. The program draws on the expertise and support of faculty and students across Columbia University to offer educators resources and opportunities to learn about creative ways of incorporating Latin American history and culture into their curriculum. 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRODUCTION INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 9 María del Pilar Riofrío and Lina Alfonso WHY YOU AND YOUR STUDENTS SHOULD VISIT A MUSEUM ............................................... 10 DESIGNER HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE .................................................................................................... 11 Sandy Chang LINKING THE MUSEUM TO THE CLASSROOM ................................................................... -

Laura Aguilar Fearlessly Reclaims Her Body and Her Journey Through Life with “Show and Tell”

Media Contacts News Travels Fast Jose Lima & Bill Spring [email protected] “A Powerful Voice for the Invisible Emerges with Raw Honesty” LAURA AGUILAR FEARLESSLY RECLAIMS HER BODY AND HER JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE WITH “SHOW AND TELL” ─ East Coast Premiere at the Frost Art Museum FIU through May 27 ─ (MIAMI) ― Lesbian, Latina and large-bodied, Laura Aguilar fearlessly reclaims her body and her journey with Show and Tell: the headline-grabbing exhibition that captured the heart of the art world during the recent PST: LA/LA, the massive art initiative led by the Getty. During this unprecedented exploration of Latin American and Latino art, Aguilar’s show was hailed as one of the most critically acclaimed of all the 70+ exhibitions at cultural institutions across Southern California. “Show and Tell” now makes it East Coast premiere in Miami at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum FIU through May 27, located on the campus of Florida International University. Laura Aguilar, Three Eagles Flying, 1990. Three gelatin silver prints. Courtesy of the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. © Laura Aguilar The first comprehensive retrospective of the American photographer’s work assembles more than one hundred photographs and video spanning three decades. A rebellious and groundbreaking Chicana, Aguilar’s retrospective has been heralded nationwide for establishing the artist as a powerful voice for diverse “invisible” communities, and for courageously disrupting repressive stereotypes of beauty and body representation. Often political as well as personal, the bold portraits cut across performative, feminist and queer art genres. The images captured through her lens reflect Aguilar’s struggles with depression, obesity, self-acceptance, prejudice and misogyny. -

Aneignung Und Ausnahme Zeitgenössische Künstlerinnen: Ihre

Aneignung und Ausnahme Zeitgenössische Künstlerinnen: Ihre ästhetischen Verfahren und ihr Status im Kunstsystem Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades an der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Europa-Universität Viadrina, Frankfurt/Oder vorgelegt von Isabelle Graw 2003 Datum der Disputation: 12. Mai 2003 2 Erster Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Anselm Haverkamp Zweite Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Beatrice von Bismarck 3 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. EINLEITUNG 5 II. THEORIEN DER ANEIGNUNG 24 II.1. Aneignungsbegriffe 24 II.1.1. Aneignung in ihrer entwicklungspsychologischen Bedeutung 24 II.1.2. Aneignung und Identifikation 28 II.1.3. Aneignung und Besitz 30 II.1.4. Ästhetische Aneignung nach Marcel Duchamp 32 II.1.5. Aneignung als soziales Privileg 36 II.1.6. Aneignung und Anerkennung 38 II.1.7. Die Normen der Anerkennung (Judith Butler) 40 II.2. Die Praxis der Aneignung 42 II.2.1 Künstlerische Aneignung: Rivalität und Faszination 42 II.2.2. Künstlerische Aneignung als Konkurrenzmuster: Hannah Wilke, Lynda Benglis, Sturtevant 45 II.2.3. Sublime Aneignung: Sherrie Levine 49 II.2.4. Aneignung in der Nachfolge Duchamps: Meret Oppenheim 51 II.2.5. Der Status von Künstlerinnen im Surrealismus 53 II.2.6. Künstlerische Aneignung als Möglichkeit der Produktion von Singularität: Helen Frankenthaler 56 II.3. Aneignungsverfahren in der Appropriation Art 58 II.3.1 Aneignung als Bestimmungsgrund einer Kunstrichtung: Appropriation Art 58 II.3.2. Der Status von Künstlerinnen in der Appropriation Art 62 II.3.3. Aneignendes Verfahren und angeeigneter Gegenstand: Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Louise Lawler 64 II.3.4. Aneignung als identitätspolitische Kategorie: Renée Green 71 II.3.5. Aneignung als Einverleibung: Andrea Fraser 77 II.3.6. -

Laura Aguilar Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2489q2tx No online items Finding Aid for the Laura Aguilar Papers, 1980-2007 CSRC.0008 Processed by Alyssa Hernandez. Chicano Studies Research Center Library 2009 144 Haines Hall Box 951544 Los Angeles, California 90095-1544 [email protected] URL: http://chicano.ucla.edu Finding Aid for the Laura Aguilar CSRC.0008 1 Papers, 1980-2007 CSRC.0008 Contributing Institution: Chicano Studies Research Center Library Title: Laura Aguilar Collection Creator: Aguilar, Laura 1959 - Identifier/Call Number: CSRC.0008 Physical Description: 4.4 linear feet(11 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1980-2007 Abstract: This collection of papers consists mainly of printed material, photos and journal articles pertaining to the work of photographer Laura Aguilar. Included are images of her work with Latinas in Los Angeles and Mexico. Chicano Studies Research Center. Language of Material: English . Access Open for research. Acquisition Information Collection was donated to the Chicano Studies Research Center by Laura Aguilar in 2005. Deed on file at the CSRC Archives office. Biography Laura Aguilar was born in 1959 in San Gabriel, California. Aguilar attended the photography program at East Los Angeles Community College and continued her studies with The Friends of Photography Workshop and Santa Fe Photographic Workshop. Her work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennial, Italy; the Los Angeles City Hall Bridge Gallery, the Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), Los Angeles Photography Center,Women's Center Gallery at the University of California in Santa Barbara, Self Help Graphics, all in CA; and the University of Illinois in Chicago, IL. She was an Artist in Residence at Light Works in Syracuse, NY in 1993; received a Brody Grant from the California Community Foundation in 1992; received an Artist in Residence grant from the California Arts Council through the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center of Los Angeles in 1991/92; and an Artist's Project Grant from LACE in that same year. -

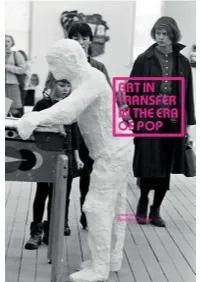

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the