Judithe Hernández and Patssi Valdez: One Path Two Journeys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Representation: Biology Politics

ON REPRESENTATION: BIOLOGY POLITICS Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art By Enma Saiz Low Residency MFA School of the Art Institute of Chicago Summer, 2020 Thesis Committee Advisor Corrine E. Fitzpatrick, Lecturer, SAIC #2 of #30 Abstract! In this thesis I write letters in an epistolary style to four artists whose work has influenced my own visual arts practice—Ana Mendieta, Doris Salcedo, Laura Aguilar, and Terri Kapsalis. The manner in which they represent the “other” in their oeuvres—respectfully, without repeating stereotypes, and sometimes elevating the “other” to ecstatic visions—has influenced my work which has to do with victims of medical experimentation, particularly African Americans and women.! Acknowledgements! A heartfelt thank you to Corrine Fitzpatrick, my writing advisor at SAIC who helped me pare down the writing to its most significant constituent parts, to Claire Pentecost, my visual arts advisor at SAIC who helped me clarify my thinking around significant concepts in the thesis, and to my son, Sam Yaziji, the emerging writer who so carefully helped me with word selection and grammar. Thank you to Marilyn Traeger for her phenomenal photography skills in shooting and editing the Torso series.! #3 of #30 On Representation: Biology Politics1 ! As a medical doctor I feel a duty to shed light on the violence and injustices su$ered by women and people of color at the hands of the medical establishment. By shedding light on these atrocities through my research-based visual arts practice, my desire is to help educate the public about the violence perpetrated against the victims of medical experimentation. -

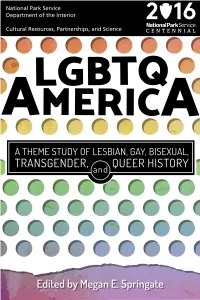

Links (Urls) to Websites Referenced in This Document Were Accurate at the Time of Publication

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. INCLUSIVE STORIES Although scholars of LGBTQ history have generally been inclusive of women, the working classes, and gender-nonconforming people, the narrative that is found in mainstream media and that many people think of when they think of LGBTQ history is overwhelmingly white, middle-class, male, and has been focused on urban communities. While these are important histories, they do not present a full picture of LGBTQ history. To include other communities, we asked the authors to look beyond the more well-known stories. Inclusion within each chapter, however, isn’t enough to describe the geographic, economic, legal, and other cultural factors that shaped these diverse histories. Therefore, we commissioned chapters providing broad historical contexts for two spirit, transgender, Latino/a, African American Pacific Islander, and bisexual communities. -

Laura Aguilar Fearlessly Reclaims Her Body and Her Journey Through Life with “Show and Tell”

Media Contacts News Travels Fast Jose Lima & Bill Spring [email protected] “A Powerful Voice for the Invisible Emerges with Raw Honesty” LAURA AGUILAR FEARLESSLY RECLAIMS HER BODY AND HER JOURNEY THROUGH LIFE WITH “SHOW AND TELL” ─ East Coast Premiere at the Frost Art Museum FIU through May 27 ─ (MIAMI) ― Lesbian, Latina and large-bodied, Laura Aguilar fearlessly reclaims her body and her journey with Show and Tell: the headline-grabbing exhibition that captured the heart of the art world during the recent PST: LA/LA, the massive art initiative led by the Getty. During this unprecedented exploration of Latin American and Latino art, Aguilar’s show was hailed as one of the most critically acclaimed of all the 70+ exhibitions at cultural institutions across Southern California. “Show and Tell” now makes it East Coast premiere in Miami at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum FIU through May 27, located on the campus of Florida International University. Laura Aguilar, Three Eagles Flying, 1990. Three gelatin silver prints. Courtesy of the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. © Laura Aguilar The first comprehensive retrospective of the American photographer’s work assembles more than one hundred photographs and video spanning three decades. A rebellious and groundbreaking Chicana, Aguilar’s retrospective has been heralded nationwide for establishing the artist as a powerful voice for diverse “invisible” communities, and for courageously disrupting repressive stereotypes of beauty and body representation. Often political as well as personal, the bold portraits cut across performative, feminist and queer art genres. The images captured through her lens reflect Aguilar’s struggles with depression, obesity, self-acceptance, prejudice and misogyny. -

Laura Aguilar Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2489q2tx No online items Finding Aid for the Laura Aguilar Papers, 1980-2007 CSRC.0008 Processed by Alyssa Hernandez. Chicano Studies Research Center Library 2009 144 Haines Hall Box 951544 Los Angeles, California 90095-1544 [email protected] URL: http://chicano.ucla.edu Finding Aid for the Laura Aguilar CSRC.0008 1 Papers, 1980-2007 CSRC.0008 Contributing Institution: Chicano Studies Research Center Library Title: Laura Aguilar Collection Creator: Aguilar, Laura 1959 - Identifier/Call Number: CSRC.0008 Physical Description: 4.4 linear feet(11 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1980-2007 Abstract: This collection of papers consists mainly of printed material, photos and journal articles pertaining to the work of photographer Laura Aguilar. Included are images of her work with Latinas in Los Angeles and Mexico. Chicano Studies Research Center. Language of Material: English . Access Open for research. Acquisition Information Collection was donated to the Chicano Studies Research Center by Laura Aguilar in 2005. Deed on file at the CSRC Archives office. Biography Laura Aguilar was born in 1959 in San Gabriel, California. Aguilar attended the photography program at East Los Angeles Community College and continued her studies with The Friends of Photography Workshop and Santa Fe Photographic Workshop. Her work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennial, Italy; the Los Angeles City Hall Bridge Gallery, the Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), Los Angeles Photography Center,Women's Center Gallery at the University of California in Santa Barbara, Self Help Graphics, all in CA; and the University of Illinois in Chicago, IL. She was an Artist in Residence at Light Works in Syracuse, NY in 1993; received a Brody Grant from the California Community Foundation in 1992; received an Artist in Residence grant from the California Arts Council through the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center of Los Angeles in 1991/92; and an Artist's Project Grant from LACE in that same year. -

Front Matter Template

Copyright by Ana Isabel Fernández de Alba 2021 The Dissertation Committee for Ana Isabel Fernández de Alba Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Scales of Seeing: Art, Los Angeles, PST:LA/LA Committee: Laura Gutiérrez, Co-Supervisor Cary Cordova, Co-Supervisor Steven D. Hoelscher George Flaherty Scales of Seeing: Art, Los Angeles, PST:LA/LA by Ana Isabel Fernández de Alba Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2021 Dedication For Juan Pablo and Ema. Acknowledgements This dissertation began as a vague possibility in summer 2017, in Mexico City, when Laura Gutiérrez first mentioned that I should look into Pacific Standard Time:LA/LA—see if I found something there. I was lost and she wanted to help. It ends now, in 2021, with me back in Mexico—in Lagos de Moreno, my hometown—after living in Los Angeles for three years. In the middle, life happened: COVID-19 and a baby girl named Ema came almost in tandem, the former in March and the latter in April 2020. I want to thank everyone that made it possible for me to finish this project. First, Laura Gutiérrez and Cary Cordova, my co-supervisors and mentors. I am incredibly lucky to have met Laura early in my career as a graduate student and, a little afterwards, Cary. Their generosity has kept me on this track, and their teaching, scholarship, and mentorship have been fundamental in sparking my intellectual curiosity. -

(MOST RECENT) Delaartcv4:29:19

Sandra de la Loza [email protected] EDUCATION 2004 MFA with emphasis in Photography, California State University, Long Beach 1994-1999 Postbaccalaureate studies in photography and education, California State University, Los Angeles. 1992 BA, Chicano Studies, University of California, Berkeley 1990 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, D.F., UC Education Abroad Program Graduate Intern, Department of Design and Installation, The National Gallery of Art, Wash- ington, D.C. Worked with the silkscreen department to produce signs and labels for several museum exhibitions. ARTISTIC PRACTICE I.SOLO & TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 Solo Exhibition (Title TBA), Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, Los Angeles, CA Mi Casa Es Su Casa, Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena, CA 2016 Dancing Cantos of an Evicted Pueblo with the Northeast Los Angeles Alliance, Avenue 50 Studio, Highland Park, CA 2014 To Oblivion! A Prelude, Echo Park Film Center, Echo Park, CA 2011 Mural Remix, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as part of the Getty Foundation’s, Pacific Standard Time initiative. 2009 The Revolution Will…, curated by Pilar Tompkins-Rivas,18th St. Art Complex, Santa Monica, CA 2008 Reciprocity with artist Brian Moss, curated by Christian Fernandez, Cerritos College Art Gallery, Cerritos, CA 2006 Mi Casa Es Su Casa, Shatford Library Latino/Chicano Heritage Reading Room, Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA 2005 Collective Synapse: A Forward Memory of the Peace and Justice Center, 33 1/3 Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2004 View from the East, Class C Gallery with Ruben Ochoa, within The California Biennial, OCC, Orange County, CA 2003 Mi Casa Es Su Casa, Werby Gallery, California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, CA II. -

Getty Foundation Grants 2002–2017

Getty Foundation Grants 2002–2017 A B “CHANGING A DEEP CULTURAL STEREOTYPE IS ABOUT AS EASY AS LANDING A ROBOT-ROVER ON MARS—NOT IMPOSSIBLE BUT SOMETHING OF A MIRACLE WHEN IT FINALLY HAPPENS. PACIFIC STANDARD TIME DID THAT, AND THE ACHIEVEMENT DESERVES RECOGNITION.” —CHRISTOPHER KNIGHT LOS ANGELES TIMES, SEPTEMBER 21, 2012 1 Introduction FOR THE VISUAL ARTS, PACIFIC STANDARD TIME is more than a time zone. It is the name of a region-wide collaboration of arts institutions across Southern California led by the Getty and specifically made possible through Getty Foundation grants. This collaboration has produced hundreds of linked art exhibitions, scholarly publications, and public programs, all of which would not have been possible without research and planning—behind-the- scenes activities necessary for the success of public projects and a pillar of the Foundation’s grantmaking since we opened our doors nearly thirty-five years ago. Pacific Standard Time was born in 2002 when arts advocate Lyn Kienholz and the late museum director Henry Hopkins called me and drew my at- tention to the fact that we were losing the history of post-World War II art in Los Angeles. Many of the main characters—artists, dealers, critics, and curators—were aging and passing away, and their papers were lost or about to be destroyed. Foundation senior staff members were intrigued by the problem, so we decided to take up the challenge. Little did we realize that what we thought would be a few grants to rescue local records would become a huge initiative. At the same time, our colleagues at the Getty Research Institute (GRI) were deeply interested in the art of the postwar period. -

Archival Body/Archival Space: Queer Remains of the Chicano Art Movement, Los Angeles, 1969-2009

ABSTRACT Title of Document: ARCHIVAL BODY/ARCHIVAL SPACE: QUEER REMAINS OF THE CHICANO ART MOVEMENT, LOS ANGELES, 1969-2009. Robert Lyle Hernandez, III, Ph.D., 2011 Directed By: Associate Professor Mary Corbin Sies, American Studies This dissertation proposes an interdisciplinary queer archive methodology I term ―archival body/archival space,‖ which recovers, interprets, and assesses the alternative archives and preservation practices of homosexual men in the Chicano Art Movement, the cultural arm of the Mexican American civil rights struggle in the U.S. Without access to systemic modes of preservation, these men generated other archival practices to resist their erasure, omission, and obscurity. The study conducts a series of archive excavations mining ―archival bodies‖ of homosexual artists from buried and unseen ―archival spaces,‖ such as: domestic interiors, home furnishings, barrio neighborhoods, and museum installations. This allows us to reconstruct the artist archive and, thus, challenge how we see, know, and comprehend ―Chicano art‖ as an aesthetic and cultural category. As such, I evidence the critical role of sexual difference within this visual vocabulary and illuminate networks of homosexual Chicano artists taking place in gay bars, alternative art spaces, salons, and barrios throughout East Los Angeles. My queer archive study model consists of five interpretative strategies: sexual agency of Chicano art, queer archival afterlife, containers of desire, archival chiaroscuro, and archive elicitation. I posit that by speaking through these artifact formations, the ―archival body‖ performs the allegorical bones and flesh of the artist, an artifactual surrogacy articulated through things. My methodological innovation has direct bearing on how sexual difference shapes the material record and the places from which these ―queer remains‖ are kept, sheltered, and displayed. -

University of Washington Press Fall 2017 University of Washington Press FALL 2017

university of washington press fall 2017 UNIvErSIty of WaShINgtoN PrESS FALL 2017 CONTENTS TITLE INDEX New Books 1 Adman 41 Michael Taylor 40 Backlist Highlights 58 Am I Safe Here? 50 Mobilizing Krishna’s World 30 Sales Representatives 64 American Indian Business 17 Nasty Women Poets 46 American Sabor 2 No Home in a Homeland 54 PUBLISHING PARTNERS Ancient Ink 18 North 14 The Art of Resistance 22 Not Fit to Stay 55 Art Gallery of New South Wales 41 Arts of Global Africa 39 On Cold Mountain 33 Fowler Museum at UCLA 38 Bike Battles 11 Onnagata 32 LM Publishers 43 Building Reuse 12 The Open Hand 47 Lost Horse Press 46 But Not Yet 48 Picturing India 28 Lynx House Press 48 Chinook Resilience 16 The Portland Black Panthers 5 Silkworm Books 44 Christian Krohg’s Naturalism 34 Power through Testimony 55 UBC Press 50 Classical Seattle 9 Queer Feminist Science Studies 20 UCLA Chicano Studies Research Press 42 Company Towns of the Pacific Northwest 13 Razor Clams 6 Complementary Contrasts 40 The Rebirth of Bodh Gaya 31 ABOUT OUR CATALOG Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts at 25 37 Receipt 46 Diasporic Media beyond the Diaspora 50 Reclaimers 9 Down with Traitors 26 Reinventing Hoodia 19 Our digital catalog is available through Dutch New York Histories 43 Risky Bodies & Techno-Intimacy 21 Edelweiss at http://edel.bz/browse/uwpress. The Emotions of Justice 33 Sacred to the Touch 35 Emperor Hirohito and the Pacific War 32 Science of the Seance 54 E-BOOKS Enduring Splendor 38 Seismic City 10 Engagement Organizing 50 Sensational Nightingales 48 Books listed with an EB ISBN are widely Engaging Imagination in Ecological Slapping the Table in Amazement 23 available in ebook editions. -

Aguilar Press Release-Final

For Immediate Release: Friday, September 1, 2017 Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell September 16, 2017-February 10, 2018 (Monterey Park, CA) – As part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, The Vincent Price Art Museum at East Los Angeles College presents Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell, the first comprehensive retrospective of American photographer Laura Aguilar, assembling more than one hundred thirty works produced over three decades. Through photographs and videos that are frequently political as well as personal, and which traverse performative, feminist, and queer art genres, Aguilar offers candid portrayals of herself, her friends and family, and LGBT and Latinx communities. Aguilar’s now iconic triptych, Three Eagles Flying (1990), set the stage for her future work by using her nude body as an overt and courageous rebellion against the colonization of Latinx identities — racial, gendered, cultural and sexual. Her practice intuitively evolved over time as she struggled to negotiate and navigate her ethnicity and sexuality, her challenges with depression and auditory dyslexia, and the acceptance of her large body. This exhibition tells the story of the artist who for most of her life struggled to communicate with words yet ironically emerged as a powerful voice for numerous and diverse marginalized groups. “This is a landmark exhibition for our institution,” said Vincent Price Art Museum Director Pilar Tompkins Rivas. “Laura Aguilar’s work is so important for its many intersections across queer, brown communities, and in relationship to feminist and Latinx scholarship. She is a highly intuitive and gifted photographer and we are honored to be able to present the first major survey of her work.” “This exhibition is also significant as it is the only solo exhibition of a Chicana artist organized by a museum for the Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative,” said exhibition curator Sybil Venegas. -

Laura Aguilar, East LA's Fearless Photographer, Dies

Laura Aguilar, East LA's Fearless Photographer, Dies Laura Aguilar, LA's groundbreaking lesbian, Chicana photographer, died. She was 58. By California News Wire Services, News Partner | Apr 26, 2018 3:38 pm ET LOS ANGELES, CA — Laura Aguilar, a Los Angeles photographer, known for chronicling the denizens of a working-class Eastside lesbian bar in the 1990s and for utilizing her nude body like sculpture in desert landscapes, has died at a nursing home in Long Beach, it was reported Thursday. She was 58. "She died in peace having spent her last day with many loving visitors," Sybil Venegas, an independent curator and friend who helped manage the artist*s affairs toward the end of her life, told the Los Angeles Times. Aguilar had long contended with diabetes and was suffering from end- stage renal failure at the time of her death, The Times reported. "Laura's passing is a profound loss," said Chon Noriega, director of the Chicano Studies Research Center, according to The Times. "She had an ability to cut through the biases and habits of thought that makes us see a smaller world than actually exists. And she did it as an expression of the stunning beauty of the human body, including her own." patch.com/california/highlandpark-ca/laura-aguilar-east-las-fearless-photographer-dies Aguilar was recently the subject of the retrospective "Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell" at the Vincent Price Art Museum on the campus of East Los Angeles College, and her photography appeared last year in the two-part exhibition "Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A." The shows helped resuscitate her profile at a time when her health was in decline. -

(MOST RECENT) Delaartcv1/21.Pages

Sandra de la Loza [email protected] EDUCATION 2004 MFA with emphasis in Photography, California State University, Long Beach 1994-1999 Postbaccalaureate studies in photography and education, California State University, Los Angeles. 1992 BA, Chicano Studies, University of California, Berkeley 1990 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, D.F., UC Education Abroad Program Graduate Intern, Department of Design and Installation, The National Gallery of Art, Wash- ington, D.C. Worked with the silkscreen department to produce signs and labels for several museum exhibitions. ARTISTIC PRACTICE I.SOLO & TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 Mi Casa Es Su Casa, Armory Center for the Arts, Pasadena, CA 2016 Dancing Cantos of an Evicted Pueblo with the Northeast Los Angeles Alliance, Avenue 50 Studio, Highland Park, CA 2014 To Oblivion! A Prelude, Echo Park Film Center, Echo Park, CA 2011 Mural Remix, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as part of the Getty Foundation’s, Pacific Standard Time initiative. 2009 The Revolution Will…, curated by Pilar Tompkins-Rivas,18th St. Art Complex, Santa Monica, CA 2008 Reciprocity with artist Brian Moss, curated by Christian Fernandez, Cerritos College Art Gallery, Cerritos, CA 2006 Mi Casa Es Su Casa, Shatford Library Latino/Chicano Heritage Reading Room, Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA 2005 Collective Synapse: A Forward Memory of the Peace and Justice Center, 33 1/3 Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2004 View from the East, Class C Gallery with Ruben Ochoa, within The California Biennial, OCC, Orange County, CA 2003 Mi Casa