Basics of Fluorescence 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 2 Contribution of Science and Technology to Global Issues

Chapter 1 Progress in Science and Technology and Socioeconomic Changes Section 2 Contribution of Science and Technology to Global Issues From the end of the 19th century to the 20th century, science and technology has rapidly advanced. Chemical industry, electrical industry and heavy industry and so on emerged and we have advanced forward to ages of mass production and mass consumption, when goods could be transported in bulk to distant locations for a short period, as physical distribution, including railways, cars and airplanes, developed. This accompanied the mass disposal of goods and mass consumption of energy, highlighting the Chapter 1 risk of depletion of limited resources, global warming, the destruction of ecosystems and the crisis in the global environment. Science and technology that changed our lives were explained in Section 1 of this chapter, but as well as changing our lives in terms of key daily lifestyle elements, science and technology are also crucial to solve global issues such as climate change, natural resource depletion and energy. There are significant expectations as to how science and technology can contribute to solve global issues. This section addresses the social contribution of science and technology in Japan domestically and internationally. 1 Contribution to Global Warming Countermeasures ○ Global warming state Climate changes caused by global warming are Average global surface temperature (land + sea) anomaly one of the most urgent problems which the world faces. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)1, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize Year in 2007, published the Synthesis Report of Fifth Changes in average global sea level Assessment Report in 2014. -

Passport to an International Career -True Globalism

Passport to an international career̶True globalism ● Maki KAWAI Professor at Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo; RIKEN The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2010 was awarded jointly to United States, it is rare for one to earn one’s Ph.D. in the United Richard F. Heck, Akira Suzuki, and Ei-ichi Negishi for their con- States like Ei-ichi Negishi. Satoru Masamune left Japan to study tributions to the development of organic synthesis that is also at the University of California, Berkley in 1957 as a Fulbright important industrially. Since palladium-catalyzed cross coupling scholar, and later became professor at Massachusetts Institute of is an area in which Japan is strong and for which it had been Technology (MIT) nurturing many organic scientists. Hiroaki widely expected that someday someone would receive the award, Suga of the Department of Chemistry, School of Science, The I honor the three winners and at the same time appreciate having University of Tokyo, and Yukishige Ito of RIKEN, who is pres- the opportunity to learn of the achievements made by many ently working on glycotrilogy at Exploratory Research for researchers engaged in this area of study. It is well known that Advanced Technology (ERATO), have both studied at MIT’s many of the Nobel Prize winners pursue their research work in Masamune Laboratory. Kazuo Nakamoto (Professor Emeritus at the United States, and Japanese winners are no exception. Marquette University in the United States, deceased June 2011) Among the fifteen winners up to 2010, the five winners of Ei-ichi of infrared or Raman spectroscopies left for the United States in Negishi (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2010), Osamu Shimomura 1958, and is famous for his editions of“ Infrared and Raman Spec- (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2008), Yoichiro Nambu (Nobel Prize tra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds,” with which I am in Physics 2008), Susumu Tonegawa (Nobel Prize in Physiology sure many of you are familiar. -

The 2009 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting: Roger Y. Tsien, Chemistry 2008

Journal of Visualized Experiments www.jove.com Video Article The 2009 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting: Roger Y. Tsien, Chemistry 2008 Roger Y. Tsien1 1 URL: https://www.jove.com/video/1575 DOI: doi:10.3791/1575 Keywords: Cellular Biology, Issue 35, GFP, Green Fluorescent Protein, IFPs, jellyfish, PKA, Calmodulin Date Published: 1/13/2010 Citation: Tsien, R.Y. The 2009 Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting: Roger Y. Tsien, Chemistry 2008. J. Vis. Exp. (35), e1575, doi:10.3791/1575 (2010). Abstract American biochemist Roger Tsien shared the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Martin Chalfie and Osamu Shimomura for their discovery and development of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). Tsien, who was born in New York in 1952 and grew up in Livingston New Jersey, began to experiment in the basement of the family home at a young age. From growing silica gardens of colorful crystallized metal salts to attempting to synthesize aspirin, these early experiments fueled what would become Tsien's lifelong interest in chemistry and colors. Tsien's first official laboratory experience was an NSF-supported summer research program in which he used infrared spectroscopy to examine how metals bind to thiocyanate, for which he was awarded a $10,000 scholarship in the Westinghouse Science Talent Search. Following graduation from Harvard in 1972, Tsien attended Cambridge University in England under a Marshall Scholarship. There he learned organic chemistry --a subject he'd hated as an undergraduate-- and looked for a way to synthesize dyes for imaging neuronal activity, generating BAPTA based optical calcium indicator dyes. Following the completion of his postdoctoral training at Cambridge in 1982, Tsien accepted a faculty position at the University of California, Berkeley. -

LB13 Osamu Shimomura 下村脩

Osamu Shimomura Life Science Building BF LB13 Osamu Shimomura 下村脩 ■Purpose of Exhibition Dr. Osamu Shimomura was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2008 “for the discovery and development of the green fluorescent protein, GFP” in the jellyfish Aequorea victoria. GFP can be incorporated into the genome of any organism as a marker that emits light in the body of the organism. For this reason, it is now possible to observe various phenomena in the bodies of living organisms over time while the cells and organisms remain alive. GFP has become an essential tool in current life science research. ■Additional Knowledge Dr. Shimomura dedicated his life’s work to unraveling the discovered that GFP emits light in living nematodes. chemical mechanism behind luminescent creatures. Moreover, Dr. Roger Y. Tsien mutated the GFP gene to During his time as a researcher at Nagoya University, he create a variety of fluorescent colors besides the succeeded in crystallizing luciferin, a luminous original green. These two doctors were awarded the substance, from the sea firefly, Vargula hilgendorfii. He Nobel Prize together with Dr. Shimomura. then began researching the blue luminous Aequorea Bioimaging is a technique for observing phenomena in the jellyfish at Princeton University in the United States. He bodies of living organisms. The world of bioimaging has eventually discovered the luminous substance Aequorin grown significantly since the discovery of GFP. By in this jellyfish and determined its structure. In the incorporating the GFP found in jellyfish into the genes course of his study of Aequorin, GFP was discovered as a of other organisms, it is possible to visualize the by-product. -

Nfap Policy Brief » October 2019

NATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR AMERICAN POLICY NFAP POLICY BRIEF» OCTOBER 2019 IMMIGRANTS AND NOBEL PRIZES : 1901- 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Immigrants have been awarded 38%, or 36 of 95, of the Nobel Prizes won by Americans in Chemistry, Medicine and Physics since 2000.1 In 2019, the U.S. winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics (James Peebles) and one of the two American winners of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (M. Stanley Whittingham) were immigrants to the United States. This showing by immigrants in 2019 is consistent with recent history and illustrates the contributions of immigrants to America. In 2018, Gérard Mourou, an immigrant from France, won the Nobel Prize in Physics. In 2017, the sole American winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was an immigrant, Joachim Frank, a Columbia University professor born in Germany. Immigrant Rainer Weiss, who was born in Germany and came to the United States as a teenager, was awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics, sharing it with two other Americans, Kip S. Thorne and Barry C. Barish. In 2016, all 6 American winners of the Nobel Prize in economics and scientific fields were immigrants. Table 1 U.S. Nobel Prize Winners in Chemistry, Medicine and Physics: 2000-2019 Category Immigrant Native-Born Percentage of Immigrant Winners Physics 14 19 42% Chemistry 12 21 36% Medicine 10 19 35% TOTAL 36 59 38% Source: National Foundation for American Policy, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, George Mason University Institute for Immigration Research. Between 1901 and 2019, immigrants have been awarded 35%, or 105 of 302, of the Nobel Prizes won by Americans in Chemistry, Medicine and Physics. -

“For the Discovery and Development of the Green Fluorescent Protein, GFP” P I X J

2008 NOBEL LAUREATES The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2008 “for the discovery and development of the green fluorescent protein, GFP” X O I P G SCAN ICAL LABORATORY ICAL ORNIA, SAN DIE ORNIA, SAN G F J. HENRIKSSON/ CALI F UNIVERSITY O TOM KLEINDINST/MARINE BIOLO TOM Osamu Shimomura Martin Chalfie Roger Y. Tsien 1/3 of the prize 1/3 of the prize 1/3 of the prize Born: 1928 Born: 1947 Born: 1952 Birthplace: Japan Birthplace: United States Birthplace: United States Nationality: Nationality: Nationality: Japanese citizen US citizen US citizen Current position: Current position: Current position: Professor Emeritus, Marine William R. Kenan Jr Professor, University of Biological Laboratory (MBL), Professor of Biological California, San Diego, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, Sciences, Columbia La Jolla, California, USA USA, and Boston University, New York, University Medical School, New York, USA Massachusetts, USA CHEMISTRY 7 Copyright Nobel Web AB 2008. Nobelprize.org, Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize medal design mark are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. 2008 NOBEL LAUREATES Speed read: Illuminating biology IBRARY L The story begins with Osamu Shimomura’s research OTO OTO H into the phenomenon of bioluminescence, in which chemical reactions within living organisms give off CIENCE P CIENCE light. While studying a glowing jellyfish in the early S / X 1960s he isolated a bioluminescent protein that gave off blue light. But the jellyfish glowed green. Further studies revealed that the protein’s blue light ANTATOMI H was absorbed by a second jellyfish protein, later P called green fluorescent protein (GFP), which in turn re-emitted green light. -

Legacy of Leadership NOBEL PRIZE WINNERS

Legacy of Leadership NOBEL PRIZE WINNERS 43 Fulbright Alumni Awarded the Nobel Prize The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State, sponsor of the Fulbright Program, recognizes 43 alumni of the Fulbright Program from 11 countries who have been awarded the Nobel Prize for their contributions to humanity. Nobel Laureates are listed in order of their award’s receipt, with the most recent first. Peter A. Diamond – U.S.A. Roy J. Glauber – U.S.A. Nobel Laureate in Economics 2010 Nobel Laureate in Physics 2005 Fulbright Scholar in Italy, 1999-00 Fulbright Scholar in France, 1954-55 Ei-ichi Negishi – Japan Nobel Laureate in Chemistry 2010 Aaron Ciechanover – Israel Fulbright Student at University of Nobel Laureate in Chemistry 2004 Pennsylvania, 1960-63 Fulbright Scholar at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1981-84 Muhammad Yunus Oliver Williamson – U.S.A. Nobel Laureate in Economics 2009 Ei-ichi Negishi Riccardo Giacconi – Italy Nobel Laureate in Physics 2002 Fulbright Scholar in Italy, 1999 Fulbright Student at Indiana University, 1956-58 Jean-Marie Le Clézio – France Nobel Laureate in Literature 2008 Masatoshi Koshiba – Japan Fulbright Scholar at University of Nobel Laureate in Physics 2002 California-Santa Cruz, 1979 Fulbright Student at University of Rochester, 1953-55 Osamu Shimomura – Japan Nobel Laureate in Chemistry 2008 George A. Akerlof – U.S.A. Fulbright Scholar at Princeton Nobel Laureate in Economics University, 1960 2001 Aaron Ciechanover Osamu Shimomura Fulbright Scholar in India, 1967-68 Leonid Hurwicz – U.S.A. Nobel Laureate in Economics 2007 Joseph Stiglitz – U.S.A. Fulbright Scholar in India, 1965-66 Nobel Laureate in Economics 2001 Fulbright Student in the United Muhammad Yunus – Bangladesh Kingdom, 1969-70 Nobel Peace Prize 2006 Fulbright Student at University of Alan G. -

Nagoya University

July 16, 2020 Do You Know Nagoya University? (full version) Yuko OKAMOTO (岡本 祐幸)� Department of Physics and Structural Biology Research Center Graduate School of Science and Center for Computational Science Graduate School of Engineering and Information Technology Center NAGOYA UNIVERSITY (名古屋大学) e-mail: okamoto{a}tb.phys.nagoya-u.ac.jp � URL: http://www.tb.phys.nagoya-u.ac.jp/index-e.html The City of Nagoya � Outline of Nagoya� • Population of 2.32 million • 1 hr 40 m to Tokyo; 30/50 m to Kyoto/Osaka by SHINKANSEN, or bullet trains Industry • Best known as an industrial powerhouse - Home of Toyota Motor Corp., Mitsubishi Heavy Ind., etc. Nagoya Castle� Downtown Nagoya� Nagoya University! (名古屋大学) � Toyoda Auditorium, donated by the Toyota Motor Corporation� Nagoya University Overview� History 1871 Established as a temporary hospital and medical school 1939 Established as Nagoya Imperial University 1947 Changed to Nagoya University Main Campus� 9 Undergraduate and 13 Graduate Schools� 9 Undergraduate Schools� Letters (arts, social Economics� Medicine� science & humanities)� Education� Information Science� Engineering� Law� Science (mathematics & Agricultural Sciences� natural science)� Total Student Population: 16,536 Undergraduate: 10,115 Graduate: 6,272 International Students: 2,289 (May 1, 2018) Many Cultural Clubs and Sports Teams (1)� 漕艇(ボート)部 [Boat] バレーボール部 [Volleyball] 水泳部 [Swimming] 陸上部 [Track and Field] 体操部 [Gymnastics] ハンドボール部 [Handball] ゴルフ部 [Golf] アメリカンフットボール部 [American Football] Many Cultural Clubs and Sports Teams (2)� フィギュア -

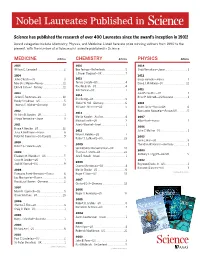

Nobel Laureates Published In

Nobel Laureates Published in Science has published the research of over 400 Laureates since the award’s inception in 1901! Award categories include Chemistry, Physics, and Medicine. Listed here are prize-winning authors from 1990 to the present, with the number of articles each Laureate published in Science. MEDICINE Articles CHEMISTRY Articles PHYSICS Articles 2015 2016 2014 William C. Campbell . 2 Ben Feringa —Netherlands........................5 Shuji Namakura—Japan .......................... 1 J. Fraser Stoddart—UK . 7 2014 2012 John O’Keefe—US...................................3 2015 Serge Haroche—France . 1 May-Britt Moser—Norway .......................11 Tomas Lindahl—US .................................4 David J. Wineland—US ............................12 Edvard I. Moser—Norway ........................11 Paul Modrich—US...................................4 Aziz Sancar—US.....................................7 2011 2013 Saul Perlmutter—US ............................... 1 2014 James E. Rothman—US ......................... 10 Brian P. Schmidt—US/Australia ................. 1 Eric Betzig—US ......................................9 Randy Schekman—US.............................5 Stefan W. Hell—Germany..........................6 2010 Thomas C. Südhof—Germany ..................13 William E. Moerner—US ...........................5 Andre Geim—Russia/UK..........................6 2012 Konstantin Novoselov—Russia/UK ............5 2013 Sir John B. Gurdon—UK . 1 Martin Karplas—Austria...........................4 2007 Shinya Yamanaka—Japan.........................3 -

Discovery of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) (Nobel Lecture)** Osamu Shimomura*

Nobel Lectures Angewandte Chemie 5590 www.angewandte.org 2009 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5590 – 5602 Angewandte Green Fluorescent Protein Chemie DOI: 10.1002/anie.200902240 Green Fluorescent Protein Discovery of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) (Nobel Lecture)** Osamu Shimomura* aequorin · bioluminescence · fluorescent proteins · Nobel Lecture 1. Biography A Wartime Childhood I was born on August 27, 1928 in the town of Fukuchiyama, Kyoto-Fu, Japan. My father Chikara was an army captain of the Fukuchiyama regiment. In the spring of 1933, my father took a post in Manchuria, which was under Japanese occupation. Because there were some insurgents in the Manchurian area, my mother Yukie, my younger brother Sadamu, and I chose to stay in Japan and moved to Sasebo, Nagasaki Prefecture, where we lived with my grandmother, Tsuki Shimomura. After the insurgents were wiped out, we moved to Renzankan, Manchuria in March 1935. A sister, Toshiko, was born here, but she died of pneumonia one year after her birth. I remember my mothers deep sorrow after Figure 1. Together with my father who returned briefly from Manchuria in 1939. Front row from left: my mother Yukie, grandmother Tsuki, Toshikos death. grandfather Kosaburo, father Chikara, younger brother Sadamu, and In early 1938, my father was transferred to an army myself behind Sadamu, together with my uncle Eijiro Sata’s family in position near the Soviet border. The rest of my family moved the back row. back to Sasebo. Mother soon departed to Manchuria again to live with my father, and Sadamu and I were in the custody of was poor. -

Osamu Shimomura (1928–2018) Chemist Who Illuminated Bioluminescence

OBITUARY COMMENT Osamu Shimomura (1928–2018) Chemist who illuminated bioluminescence. rowing up during one of Shimomura, his family and his the darkest times in history, research colleagues spent 19 sum Osamu Shimomura devoted mers at Friday Harbor, collecting Ghis long and fruitful career to under hundreds of thousands of jellyfish to standing how creatures emit light. obtain enough of the elusive material He discovered green fluorescent pro for a full structural analysis. Until a tein (GFP), with which — decades way of making genetically engi later — biomedical researchers neered aequorin became available in began to monitor the workings of the 1990s, Shimomura freely shared proteins in living tissue, and to con his carefully harvested stocks with firm the insertion of genes. For that laboratories the world over. discovery, he shared the Nobel Prize It was in the process of purifying in Chemistry in 2008 with neuro aequorin that Shimomura discov biologist Martin Chalfie and the late ered small amounts of GFP, which Roger Tsien, a chemist. fluoresces green when aequorin Shimomura, who died in emits its blue light. It took him and Nagasaki, Japan, on 19 October, was his team until 1979 to accumulate MARINE BIOLOGICAL LABORATORY/TOM KLEINDINST LABORATORY/TOM MARINE BIOLOGICAL the first to show that a protein could enough to explore how the protein contain the lightemitting appara works. Shimomura described GFP’s tus within its own peptide chain, rather than the laboratory of organic chemist Yoshimasa unprecedented incorporation of the light interacting with a separate lightemitting Hirata at Nagoya University, and his lifelong emitting function within the protein chain compound. -

Nobel Lecture by Osamu Shimomura

DISCOVERY OF GREEN FLUORESCENT PROTEIN, GFP Nobel Lecture, December 8, 2008 by Osamu Shimomura Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA. PROLOGUE I discovered the green fluorescent protein GFP from the jellyfish Aequorea aequorea in 1961 as a byproduct of the Ca-sensitive photoprotein aequorin (Shimomura et al., 1962; Johnson et al., 1962), and identified its chro- mophore in 1979 (Shimomura, 1979). GFP was a beautiful protein but it remained useless for the next 30 years after the discovery. My story begins in 1945, the year the city of Nagasaki was destroyed by an atomic bomb and World War II ended. At that time I was a 16-year old high school student, and I was working at a factory about 15 km northeast of Nagasaki. I watched the B-29 that carried the atomic bomb heading toward Nagasaki, then soon I was exposed to a blinding bright flash and a strong pressure wave that were caused by a gigantic explosion. I was lucky to sur- vive the war. In the mess after the war, however, I could not find any school to attend. I idled for 2 years, and then I learned that the pharmacy school of Nagasaki Medical College, which had been completely destroyed by the atomic bomb, was going to open a temporary campus near my home. I ap- plied to the pharmacy school and was accepted. Although I didn’t have any interest in pharmacy, it was the only way that I could have some education. After graduating from the pharmacy school, I worked as a teaching assistant at the same school, which was reorganized as a part of Nagasaki University.