PRAGMATIC COMPETENCE and the CHALLENGE of SPEECH EXPRESSION and PRECISION Thesis Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empirical Base of Linguistics: Grammaticality Judgments and Linguistic Methodology

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05b2s4wg ISBN 978-3946234043 Author Schütze, Carson T Publication Date 2016-02-01 DOI 10.17169/langsci.b89.101 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are managed by: Language Science Press, Berlin Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language Classics in Linguistics 2 science press Classics in Linguistics Chief Editors: Martin Haspelmath, Stefan Müller In this series: 1. Lehmann, Christian. Thoughts on grammaticalization 2. Schütze, Carson T. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology 3. Bickerton, Derek. Roots of language ISSN: 2366-374X The empirical base of linguistics Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology Carson T. Schütze language science press Carson T. Schütze. 2019. The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology (Classics in Linguistics 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/89 © 2019, Carson T. Schütze Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-946234-02-9 (Digital) 978-3-946234-03-6 (Hardcover) 978-3-946234-04-3 (Softcover) 978-1-523743-32-2 -

Speechreading for Information Gathering

Speechreading for information gathering: A survey of scientific sources1 Ruth Campbell Ph.D, with Tara-Jane Ellis Mohammed, Ph.D Division of Psychology and Language Sciences University College London Spring 2010 1 Contents 1 Introduction 2 Questions (and answers) 3 Chronologically organised survey of tests of Speechreading (Tara Mohammed) 4 Further Sources 5 Biographical notes 6 References 2 1 Introduction 1.1 This report aims to clarify what is and is not possible in relation to speechreading, and to the development of speechreading skills. It has been designed to be used by agencies which may wish to make use of speechreading for a variety of reasons, but it focuses on requirements in relation to understanding silent speech for information gathering purposes. It provides the main evidence base for the report : Guidance for organizations planning to use lipreading for information gathering (Ruth Campbell) - a further outcome of this project. 1.2 The report is based on published, peer-reviewed findings wherever possible. There are many gaps in the evidence base. Research to date has focussed on watching a single talker’s speech actions. The skills of lipreaders have been scrutinised primarily to help improve communication between the lipreader (typically a deaf or deafened person) and the speaking hearing population. Tests have been developed to assess individual differences in speechreading skill. Many of these are tabulated below (section 3). It should be noted however that: There is no reliable scientific research data related to lipreading conversations between different talkers. There are no published studies of expert forensic lipreaders’ skills in relation to information gathering requirements (transcript preparation, accuracy and confidence). -

An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS

An Inefficient Choice: An Empirical Test of Media Richness and Electronic Propinquity THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ted Michael Dickinson Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. Jesse Fox, Advisor Dr. Brandon van der Heide Copyrighted by Ted Michael Dickinson 2012 Abstract Media richness theory is frequently cited when discussing the strengths of various media in allowing for immediate feedback, personalization of messages, the ability to use natural language, and transmission of nonverbal cues. Most studies do not, however, address the theory’s main argument that people faced with equivocal message tasks will complete those tasks faster by choosing interpersonal communication media with these features. Participants in the present study either chose or were assigned to a medium and then timed on their completion of an equivocal message task. Findings support media richness theory’s prediction; those using videoconferencing to complete the task did so in less time than those using the leaner medium of text chat. Measures of electronic propinquity, a theory proposing a sense of psychological nearness to others in a mediated communication, were also tested as a potential adjunct to media richness theory’s predictions of medium selection, with mixed results. Keywords: media richness, electronic propinquity, media selection, computer-mediated communication, nonverbal -

The Impact of Pushed Output on Accuracy and Fluency Of

Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 2(2), (July, 2014) 51-72 51 Content list available at www.urmia.ac.ir/ijltr Urmia University The impact of pushed output on accuracy and fluency of Iranian EFL learners’ speaking Aram Reza Sadeghi Beniss a, Vahid Edalati Bazzaz a, * a Semnan University, Iran A B S T R A C T The current study attempted to establish baseline quantitative data on the impacts of pushed output on two components of speaking (i.e., accuracy and fluency). To achieve this purpose, 30 female EFL learners were selected from a whole population pool of 50 based on the standard test of IELTS interview and were randomly assigned into an experimental group and a control group. The participants in the experimental group received pushed output treatment while the students in the control group received non-pushed output instruction. The data were collected through IELTS interview and then the interview of each participant was separately tape-recorded and later transcribed and coded to measure accuracy and fluency. Then, the independent samples t-test was employed to analyze the collected data. The results revealed that the experimental group outperformed the control group in accuracy. In contrast, findings substantiated that pushed output had no impact on fluency. The positive impact of pushed output demonstrated in this study is consistent with the hypothesized function of Swain’s (1985) pushed output. The results can provide some useful insights into syllabus design and English language teaching. Keywords: pushed output; accuracy; fluency; EFL speaking © Urmia University Press A R T I C L E S U M M A R Y Received: 28 Jan. -

Preprint Corpus Analysis in Forensic Linguistics

Nini, A. (2020). Corpus analysis in forensic linguistics. In Carol A. Chapelle (ed), The Concise Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, 313-320, Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Corpus Analysis in Forensic Linguistics Andrea Nini Abstract This entry is an overview of the applications of corpus linguistics to forensic linguistics, in particular to the analysis of language as evidence. Three main areas are described, following the influence that corpus linguistics has had on them in recent times: the analysis of texts of disputed authorship, the provision of evidence in cases of trademark disputes, and the analysis of disputed meanings in criminal or civil cases. In all of these areas considerable advances have been made that revolve around the use of corpus data, for example, to study forensically realistic corpora for authorship analysis, or to provide naturally occurring evidence in cases of trademark disputes or determination of meaning. Using examples from real-life cases, the entry explains how corpus analysis is therefore gradually establishing itself as the norm for solving certain forensic problems and how it is becoming the main methodological approach for forensic linguistics. Keywords Authorship Analysis; Idiolect; Language as Evidence; Ordinary Meaning; Trademark This entry focuses on the use of corpus linguistics methods and techniques for the analysis of forensic data. “Forensic linguistics” is a very general term that broadly refers to two areas of investigation: the analysis of the language of the law and the analysis of language evidence in criminal or civil cases. The former, which often takes advantage of corpus methods, includes areas as wide as the study of the language of the judicial process and courtroom interaction (e.g., Tkačuková, 2015), the study of written legal documents (e.g., Finegan, 2010), and the investigation of interactions in police interviews (e.g., Carter, 2011). -

The Impact of Task Complexity on the Development of L2 Grammar

English Teaching, Vol. 75, No. 1, Spring 2020, pp. 93-117 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.75.1.202003.93 http://journal.kate.or.kr The Impact of Task Complexity on the Development of L2 Grammar Ji-Yung Jung* Jung, Ji-Yung. (2020). The impact of task complexity on the development of L2 grammar. English Teaching, 75(1), 93-117. The Cognition Hypothesis postulates that more cognitively complex tasks can trigger more accurate and complex language production, thereby advancing second language (L2) development. However, few studies have directly examined the relationship between task manipulations and L2 development. To address this gap, this article reviews, via an analytic approach, nine empirical studies that investigated the impact of task complexity on L2 development in the domain of morphosyntax. The studies are categorized into two groups based on if they include learner-learner interaction or a focus on form (FonF) treatment provided by an expert interlocutor. The results indicate that the findings of the studies, albeit partially mixed, tend to support the predictions of the Cognition Hypothesis. More importantly, a further analysis reveals seven key methodological issues that need to be considered in future research: target linguistic domains, different types of FonF, the complexity of the target structure, task types, outcome measures, the use of introspective methods, and the need of more empirical studies and replicable study designs. Key words: task complexity, Cognition Hypothesis, resource-directing and resource-dispersing -

CONTENT Unit I 2-18 Communication and Language INTRODUCTION to LINGUISTICS Major Linguists and Their Contribution

1 CONTENT Unit I 2-18 Communication and Language INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTICS Major Linguists and their Contribution Unit II 19-27 Phonology of English and Phonetics Mechanism of Speech Production Organs of speech The Respiratory System The Phonatory System The Articulatory System The Air-stream Mechanism Unit III 29-43 Phonology of English and Phonetics (Continued) Description and Classification of Vowels and Consonants Description of Vowel Sounds Description of Pure Vowels in English Description of Dipthongs or Glides in English Occurrence of Vowel Sounds in English Description of Consonant Sounds Unit IV 44-56 STRESS AND INTONATION Word Accent/Stress Intonation Unit V 57-70 SOCIOLINUISTICS Definitions of Sociolinguistics Language Variation or Varieties of Language Dialects Sociolect Idiolect Register Language Contact: Pidgin and Creole 2 UNIT-I INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTICS 1.0 1.1 Linguistics/lɪŋˈɡwɪstɪks/ refers to the scientific study of language and its structure, including the study of grammar, syntax, and phonetics. Specific branches of linguistics include sociolinguistics, dialectology, psycholinguistics, computational linguistics, comparative linguistics, and structural linguistics. WHAT IS LINGUISTICS? Linguistics is defined as the scientific study of language.It is the systematic study of the elements of language and the principles governing their combination and organization. Linguistics provides for a rigorous experimentation with the elements or aspects of language that are actually in use by the speech community. It is based on observation and the data collected thereby from the users of the language, a scientific analysis is made by the investigator and at the end of it he comes out with a satisfactory explanation relating to his field of study. -

The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 414 CS 504 984 AUTHOR McQuillen, Jeffrey S.;Ivy, Diana K. TITLE The Basic Course in Speech Communication: Past, Present and Future. PUB DATE [82] NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Basic Skills; Course Content; Course Organization; Educational Assessment; *Educational History; Educational Trends; Higher Education; *Speech Communication; *Speech Curriculum; Speech Instruction ABSTRACT Acknowledging the need for objective evaluation of. the focus and organization of the basic speechcommunication course, this paper reviews the progress of the basic course bytracing its changes and development. The first portion of the paperdiscusses the evolution of the basic course from the 1950s to the present,giving specific attention to historical modifications in thebasic course's orientation and focus. The second, portion of the paperaddresses questions concerning the current orientation,responsiveness, and appropriateness of the basic course, and reviewspromising answers to these questions. (HTH) ********************************************************************** * * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that canbe made * * from the original document. *********************************************************************** BEST COPY AVAILABLE THE BASIC COURSE IN SPEECH COMMUNICATION: Past, present and r--1 future CT r\J LtJ Jeffrey S. McQuillen Assistant Professor Speech Communication Program Texas ALCM University College Station, TX 77843 (409) 845-8328 Diana K. Ivy Doctoral Candidate Communication Department University of Oklahoma Norman, Ok 73019 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL. RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERICI .>\Thisdocument has been reproduced as eceived from the person or organization originating it Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality Points of view or opinions :riled in this dorm merit do not necessarily represent official NIE position or petit. -

UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech

UNITED NATIONS STRATEGY AND PLAN OF ACTION ON HATE SPEECH Foreword Around the world, we are seeing a disturbing groundswell of xenophobia, racism and intolerance – including rising anti-Semitism, anti-Muslim hatred and persecution of Christians. Social media and other forms of communication are being exploited as platforms for bigotry. Neo-Nazi and white supremacy movements are on the march. Public discourse is being weaponized for political gain with incendiary rhetoric that stigmatizes and dehumanizes minorities, migrants, refugees, women and any so-called “other”. This is not an isolated phenomenon or the loud voices of a few people on the fringe of society. Hate is moving into the mainstream – in liberal democracies and authoritarian systems alike. And with each broken norm, the pillars of our common humanity are weakened. Hate speech is a menace to democratic values, social stability and peace. As a matter of principle, the United Nations must confront hate speech at every turn. Silence can signal indifference to bigotry and intolerance, even as a situation escalates and the vulnerable become victims. Tackling hate speech is also crucial to deepen progress across the United Nations agenda by helping to prevent armed conflict, atrocity crimes and terrorism, end violence against women and other serious violations of human rights, and promote peaceful, inclusive and just societies. Addressing hate speech does not mean limiting or prohibiting freedom of speech. It means keeping hate speech from escalating into something more dangerous, particularly incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence, which is prohibited under international law. The United Nations has a long history of mobilizing the world against hatred of all kinds through wide-ranging action to defend human rights and advance the rule of law. -

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

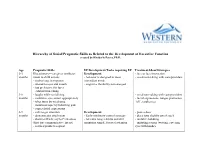

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Identifying Idiolect in Forensic Authorship Attribution: an N-Gram Textbite Approach Alison Johnson & David Wright University of Leeds

Identifying idiolect in forensic authorship attribution: an n-gram textbite approach Alison Johnson & David Wright University of Leeds Abstract. Forensic authorship attribution is concerned with identifying authors of disputed or anonymous documents, which are potentially evidential in legal cases, through the analysis of linguistic clues left behind by writers. The forensic linguist “approaches this problem of questioned authorship from the theoretical position that every native speaker has their own distinct and individual version of the language [. ], their own idiolect” (Coulthard, 2004: 31). However, given the diXculty in empirically substantiating a theory of idiolect, there is growing con- cern in the Veld that it remains too abstract to be of practical use (Kredens, 2002; Grant, 2010; Turell, 2010). Stylistic, corpus, and computational approaches to text, however, are able to identify repeated collocational patterns, or n-grams, two to six word chunks of language, similar to the popular notion of soundbites: small segments of no more than a few seconds of speech that journalists are able to recognise as having news value and which characterise the important moments of talk. The soundbite oUers an intriguing parallel for authorship attribution studies, with the following question arising: looking at any set of texts by any author, is it possible to identify ‘n-gram textbites’, small textual segments that characterise that author’s writing, providing DNA-like chunks of identifying ma- terial? Drawing on a corpus of 63,000 emails and 2.5 million words written by 176 employees of the former American energy corporation Enron, a case study approach is adopted, Vrst showing through stylistic analysis that one Enron em- ployee repeatedly produces the same stylistic patterns of politely encoded direc- tives in a way that may be considered habitual. -

Ian Davison Supervisor: Dr. Jenefer Philp Phd in Applied Linguistics By

Department of Linguistics and English Language Student: Ian Davison Supervisor: Dr. Jenefer Philp PhD in Applied Linguistics by Thesis and Coursework Thesis submitted for PhD in Applied Linguistics “The Effects of Carrying out Collaborative Writing on the Individual Writing Proficiency of English Second Language Learners in an English for Academic Purposes Program” Abstract This quasi-experimental classroom-based study (n=128) looks at what students in an English for Academic Purposes Program (EAP) learn from the process of writing collaboratively and how this affects the individual writing that they subsequently produce. This is compared to how individual writing is affected by carrying out independent writing. Previous research carried out by Storch (2005), Storch and Wigglesworth (2007), Wigglesworth and Storch (2009), Dobao (2012), McDonough, De Vleeschauwer and Crawford (2018) and Villarreal and Gil-Sarratea (2019) found that writing produced collaboratively (by pairs or groups of writers) was more accurate than writing produced independently. This thesis suggests that individual students can learn from the process of writing collaboratively and that their own subsequent individual writing could become more accurate or improve as a result. Analysis of individual pre and post-test writing completed before and after two groups of students had carried out a series of writing tasks either collaboratively (collaborative writing group, n=64) or independently (independent writing group, n=64) over a period of 8 weeks revealed that accuracy increased to a significantly greater degree in the post-test writing of students from the collaborative group than in the same writing of students from the independent writing group. On the other hand, there were similar statistically significant increases in fluency and lexical complexity in the post-test writing of both groups and in the coherence and cohesion of post-test writing although syntactic complexity did not increase significantly in either group.