Passband Wireless Communication Introduction Baseband

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems

63 3 Characterization of Communication Signals and Systems 3.1 Representation of Bandpass Signals and Systems Narrowband communication signals are often transmitted using some type of carrier modulation. The resulting transmit signal s(t) has passband character, i.e., the bandwidth B of its spectrum S(f) = s(t) is much smaller F{ } than the carrier frequency fc. S(f) B f f f − c c We are interested in a representation for s(t) that is independent of the carrier frequency fc. This will lead us to the so–called equiv- alent (complex) baseband representation of signals and systems. Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 64 3.1.1 Equivalent Complex Baseband Representation of Band- pass Signals Given: Real–valued bandpass signal s(t) with spectrum S(f) = s(t) F{ } Analytic Signal s+(t) In our quest to find the equivalent baseband representation of s(t), we first suppress all negative frequencies in S(f), since S(f) = S( f) is valid. − The spectrum S+(f) of the resulting so–called analytic signal s+(t) is defined as S (f) = s (t) =2 u(f)S(f), + F{ + } where u(f) is the unit step function 0, f < 0 u(f) = 1/2, f =0 . 1, f > 0 u(f) 1 1/2 f Schober: Signal Detection and Estimation 65 The analytic signal can be expressed as 1 s+(t) = − S+(f) F 1{ } = − 2 u(f)S(f) F 1{ } 1 = − 2 u(f) − S(f) F { } ∗ F { } 1 The inverse Fourier transform of − 2 u(f) is given by F { } 1 j − 2 u(f) = δ(t) + . -

2 the Wireless Channel

CHAPTER 2 The wireless channel A good understanding of the wireless channel, its key physical parameters and the modeling issues, lays the foundation for the rest of the book. This is the goal of this chapter. A defining characteristic of the mobile wireless channel is the variations of the channel strength over time and over frequency. The variations can be roughly divided into two types (Figure 2.1): • Large-scale fading, due to path loss of signal as a function of distance and shadowing by large objects such as buildings and hills. This occurs as the mobile moves through a distance of the order of the cell size, and is typically frequency independent. • Small-scale fading, due to the constructive and destructive interference of the multiple signal paths between the transmitter and receiver. This occurs at the spatialscaleoftheorderofthecarrierwavelength,andisfrequencydependent. We will talk about both types of fading in this chapter, but with more emphasis on the latter. Large-scale fading is more relevant to issues such as cell-site planning. Small-scale multipath fading is more relevant to the design of reliable and efficient communication systems – the focus of this book. We start with the physical modeling of the wireless channel in terms of elec- tromagnetic waves. We then derive an input/output linear time-varying model for the channel, and define some important physical parameters. Finally, we introduce a few statistical models of the channel variation over time and over frequency. 2.1 Physical modeling for wireless channels Wireless channels operate through electromagnetic radiation from the trans- mitter to the receiver. -

7.3.7 Video Cassette Recorders (VCR) 7.3.8 Video Disk Recorders

/7 7.3.5 Fiber-Optic Cables (FO) 7.3.6 Telephone Company Unes (TELCO) 7.3.7 Video Cassette Recorders (VCR) 7.3.8 Video Disk Recorders 7.4 Transmission Security 8. Consumer Equipment Issues 8.1 Complexity of Receivers 8.2 Receiver Input/Output Characteristics 8.2.1 RF Interface 8.2.2 Baseband Video Interface 8.2.3 Baseband Audio Interface 8.2.4 Interfacing with Ancillary Signals 8.2.5 Receiver Antenna Systems Requirements 8.3 Compatibility with Existing NTSC Consumer Equipment 8.3.1 RF Compatibility 8.3.2 Baseband Video Compatibility 8.3.3 Baseband Audio Compatibility 8.3.4 IDTV Receiver Compatibility 8.4 Allows Multi-Standard Display Devices 9. Other Considerations 9.1 Practicality of Near-Term Technological Implementation 9.2 Long-Term Viability/Rate of Obsolescence 9.3 Upgradability/Extendability 9.4 Studio/Plant Compatibility Section B: EXPLANATORY NOTES OF ATTRIBUTES/SYSTEMS MATRIX Items on the Attributes/System Matrix for which no explanatory note is provided were deemed to be self-explanatory. I. General Description (Proponent) section I shall be used by a system proponent to define the features of the system being proposed. The features shall be defined and organized under the headings ot the following subsections 1 through 4. section I. General Description (Proponent) shall consist of a description of the proponent system in narrative form, which covers all of the features and characteris tics of the system which the proponent wishe. to be included in the public record, and which will be used by various groups to analyze and understand the system proposed, and to compare with other propo.ed systems. -

Baseband Harmonic Distortions in Single Sideband Transmitter and Receiver System

Baseband Harmonic Distortions in Single Sideband Transmitter and Receiver System Kang Hsia Abstract: Telecommunications industry has widely adopted single sideband (SSB or complex quadrature) transmitter and receiver system, and one popular implementation for SSB system is to achieve image rejection through quadrature component image cancellation. Typically, during the SSB system characterization, the baseband fundamental tone and also the harmonic distortion products are important parameters besides image and LO feedthrough leakage. To ensure accurate characterization, the actual frequency locations of the harmonic distortion products are critical. While system designers may be tempted to assume that the harmonic distortion products are simply up-converted in the same fashion as the baseband fundamental frequency component, the actual distortion products may have surprising results and show up on the different side of spectrum. This paper discusses the theory of SSB system and the actual location of the baseband harmonic distortion products. Introduction Communications engineers have utilized SSB transmitter and receiver system because it offers better bandwidth utilization than double sideband (DSB) transmitter system. The primary cause of bandwidth overhead for the double sideband system is due to the image component during the mixing process. Given data transmission bandwidth of B, the former requires minimum bandwidth of B whereas the latter requires minimum bandwidth of 2B. While the filtering of the image component is one type of SSB implementation, another type of SSB system is to create a quadrature component of the signal and ideally cancels out the image through phase cancellation. M(t) M(t) COS(2πFct) Baseband Message Signal (BB) Modulated Signal (RF) COS(2πFct) Local Oscillator (LO) Signal Figure 1. -

Baseband Video Testing with Digital Phosphor Oscilloscopes

Application Note Baseband Video Testing With Digital Phosphor Oscilloscopes Video signals are complex pose instrument that can pro- This application note demon- waveforms comprised of sig- vide accurate information – strates the use of a Tektronix nals representing a picture as quickly and easily. Finally, to TDS 700D-series Digital well as the timing informa- display all of the video wave- Phosphor Oscilloscope to tion needed to display the form details, a fast acquisi- make a variety of common picture. To capture and mea- tion technology teamed with baseband video measure- sure these complex signals, an intensity-graded display ments and examines some of you need powerful instru- give the confidence and the critical measurement ments tailored for this appli- insight needed to detect and issues. cation. But, because of the diagnose problems with the variety of video standards, signal. you also need a general-pur- Copyright © 1998 Tektronix, Inc. All rights reserved. Video Basics Video signals come from a for SMPTE systems, etc. The active portion of the video number of sources, including three derived component sig- signal. Finally, the synchro- cameras, scanners, and nals can then be distributed nization information is graphics terminals. Typically, for processing. added. Although complex, the baseband video signal Processing this composite signal is a sin- begins as three component gle signal that can be carried analog or digital signals rep- In the processing stage, video on a single coaxial cable. resenting the three primary component signals may be combined to form a single Component Video Signals. color elements – the Red, Component signals have an Green, and Blue (RGB) com- composite video signal (as in NTSC or PAL systems), advantage of simplicity in ponent signals. -

Digital Baseband Modulation Outline • Later Baseband & Bandpass Waveforms Baseband & Bandpass Waveforms, Modulation

Digital Baseband Modulation Outline • Later Baseband & Bandpass Waveforms Baseband & Bandpass Waveforms, Modulation A Communication System Dig. Baseband Modulators (Line Coders) • Sequence of bits are modulated into waveforms before transmission • à Digital transmission system consists of: • The modulator is based on: • The symbol mapper takes bits and converts them into symbols an) – this is done based on a given table • Pulse Shaping Filter generates the Gaussian pulse or waveform ready to be transmitted (Baseband signal) Waveform; Sampled at T Pulse Amplitude Modulation (PAM) Example: Binary PAM Example: Quaternary PAN PAM Randomness • Since the amplitude level is uniquely determined by k bits of random data it represents, the pulse amplitude during the nth symbol interval (an) is a discrete random variable • s(t) is a random process because pulse amplitudes {an} are discrete random variables assuming values from the set AM • The bit period Tb is the time required to send a single data bit • Rb = 1/ Tb is the equivalent bit rate of the system PAM T= Symbol period D= Symbol or pulse rate Example • Amplitude pulse modulation • If binary signaling & pulse rate is 9600 find bit rate • If quaternary signaling & pulse rate is 9600 find bit rate Example • Amplitude pulse modulation • If binary signaling & pulse rate is 9600 find bit rate M=2à k=1à bite rate Rb=1/Tb=k.D = 9600 • If quaternary signaling & pulse rate is 9600 find bit rate M=2à k=1à bite rate Rb=1/Tb=k.D = 9600 Binary Line Coding Techniques • Line coding - Mapping of binary information sequence into the digital signal that enters the baseband channel • Symbol mapping – Unipolar - Binary 1 is represented by +A volts pulse and binary 0 by no pulse during a bit period – Polar - Binary 1 is represented by +A volts pulse and binary 0 by –A volts pulse. -

The Future of Passive Multiplexing & Multiplexing Beyond

The Future of Passive Multiplexing & Multiplexing Beyond 10G From 1G to 10G was easy But Beyond 10G? 1G CWDM/DWDM 10G CWDM/DWDM 25G 40G Dark Fiber Passive Multiplexer 100G ? 400G Ingredients for Multiplexing 1) Dark Fiber 2) Multiplexers 3) Light : Transceivers Ingredients for Multiplexing 1) Dark Fiber 2 Multiplexer 3 Light + Transceiver Dark Fiber Attenuation → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → Dispersion → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → Dark Fiber Dispersion @1G DWDM max 200km → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → @10G DWDM max 80km → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → @25G DWDM max 15km → 0 km → → 40 km → → 80 km → Dark Fiber Attenuation → 80 km → 1310nm Window 1550nm/DWDM Dispersion → 80 km → Ingredients for Multiplexing 1 Dark FiBer 2) Multiplexers 3 Light + Transceiver Passive Mux Multiplexers 2 types • Cascaded TFF • AWG 95% of all Communication -Larger Multiplexers such as 40Ch/96Ch Multiplexers TFF: Thin film filter • Metal or glass tuBes 2cm*4mm • 3 fiBers: com / color / reflect • Each tuBe has 0.3dB loss • 95% of Muxes & OADM Multiplexers ABS casing Multiplexers AWG: arrayed wave grading -Larger muxes such as 40Ch/96Ch -Lower loss -Insertion loss 40ch = 3.0dB DWDM33 Transmission Window AWG Gaussian Fit Attenuation DWDM33 Low attenuation Small passband Reference passBand DWDM33 Isolation Flat Top Higher attenuation Wide passband DWDM light ALL TFF is Flat top Transmission Wave Types Flat Top: OK DWDM 10G Coherent 100G Gaussian Fit not OK DWDM PAM4 Ingredients for Multiplexing 1 Dark FiBer 2 Multiplexer 3) Light: Transceivers ITU Grids LWDM DWDM CWDM Attenuation -

Performance Evaluation of Power-Line Communication Systems for LIN-Bus Based Data Transmission

electronics Article Performance Evaluation of Power-Line Communication Systems for LIN-Bus Based Data Transmission Martin Brandl * and Karlheinz Kellner Department of Integrated Sensor Systems, Danube University, 3500 Krems, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-2732-893-2790 Abstract: Powerline communication (PLC) is a versatile method that uses existing infrastructure such as power cables for data transmission. This makes PLC an alternative and cost-effective technology for the transmission of sensor and actuator data by making dual use of the power line and avoiding the need for other communication solutions; such as wireless radio frequency communication. A PLC modem using DSSS (direct sequence spread spectrum) for reliable LIN-bus based data transmission has been developed for automotive applications. Due to the almost complete system implementation in a low power microcontroller; the component cost could be radically reduced which is a necessary requirement for automotive applications. For performance evaluation the DSSS modem was compared to two commercial PLC systems. The DSSS and one of the commercial PLC systems were designed as a direct conversion receiver; the other commercial module uses a superheterodyne architecture. The performance of the systems was tested under the influence of narrowband interference and additive Gaussian noise added to the transmission channel. It was found that the performance of the DSSS modem against singleton interference is better than that of commercial PLC transceivers by at least the processing gain. The performance of the DSSS modem was at least 6 dB better than the other modules tested under the influence of the additive white Gaussian noise on the transmission channel at data rates of 19.2 kB/s. -

Passband Data Transmission I Introduction in Digital Passband

Passband Data Transmission I References Phase-shift keying Chapter 4.1-4.3, S. Haykin, Communication Systems, Wiley. J.1 Introduction In baseband pulse transmission, a data stream represented in the form of a discrete pulse-amplitude modulated (PAM) signal is transmitted over a low- pass channel. In digital passband transmission, the incoming data stream is modulated onto a carrier with fixed frequency and then transmitted over a band-pass channel. J.2 1 Passband digital transmission allows more efficient use of the allocated RF bandwidth, and flexibility in accommodating different baseband signal formats. Example Mobile Telephone Systems GSM: GMSK modulation is used (a variation of FSK) IS-54: π/4-DQPSK modulation is used (a variation of PSK) J.3 The modulation process making the transmission possible involves switching (keying) the amplitude, frequency, or phase of a sinusoidal carrier in accordance with the incoming data. There are three basic signaling schemes: Amplitude-shift keying (ASK) Frequency-shift keying (FSK) Phase-shift keying (PSK) J.4 2 ASK PSK FSK J.5 Unlike ASK signals, both PSK and FSK signals have a constant envelope. PSK and FSK are preferred to ASK signals for passband data transmission over nonlinear channel (amplitude nonlinearities) such as micorwave link and satellite channels. J.6 3 Classification of digital modulation techniques Coherent and Noncoherent Digital modulation techniques are classified into coherent and noncoherent techniques, depending on whether the receiver is equipped with a phase- recovery circuit or not. The phase-recovery circuit ensures that the local oscillator in the receiver is synchronized to the incoming carrier wave (in both frequency and phase). -

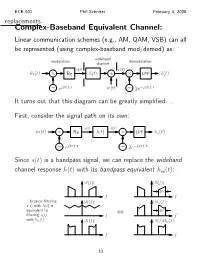

The Complex-Baseband Equivalent Channel Model

ECE-501 Phil Schniter February 4, 2008 replacements Complex-Baseband Equivalent Channel: Linear communication schemes (e.g., AM, QAM, VSB) can all be represented (using complex-baseband mod/demod) as: wideband modulation demodulation channel s(t) r(t) m˜ (t) Re h(t) + LPF v˜(t) × × j2πfct w(t) j2πfct ∼ e ∼ 2e− It turns out that this diagram can be greatly simplified. First, consider the signal path on its own: s(t) x(t) m˜ (t) Re h(t) LPF v˜s(t) × × j2πfct j2πfct ∼ e ∼ 2e− Since s(t) is a bandpass signal, we can replace the wideband channel response h(t) with its bandpass equivalent hbp(t): S(f) S(f) | | | | 2W f f ...because filtering H(f) Hbp(f) s(t) with h(t) is | | | | equivalent to 2W filtering s(t) f ⇔ f with hbp(t): X(f) S(f)H (f) | | | bp | f f 33 ECE-501 Phil Schniter February 4, 2008 Then, notice that j2πfct j2πfct s(t) h (t) 2e− = s(τ)h (t τ)dτ 2e− ∗ bp bp − · # ! " j2πfcτ j2πfc(t τ) = s(τ)2e− h (t τ)e− − dτ bp − # j2πfct j2πfct = s(t)2e− h (t)e− , ∗ bp which means we can rewrit!e the block di"agr!am as " s(t) j2πfct m˜ (t) Re hbp(t)e− LPF v˜s(t) × × j2πfct j2πfct ∼ e ∼ 2e− j2πfct We can now reverse the order of the LPF and hbp(t)e− (since both are LTI systems), giving s(t) j2πfct m˜ (t) Re LPF hbp(t)e− v˜s(t) × × j2πfct j2πfct ∼ e ∼ 2e− Since mod/demod is transparent (with synched oscillators), it can be removed, simplifying the block diagram to j2πfct m˜ (t) hbp(t)e− v˜s(t) 34 ECE-501 Phil Schniter February 4, 2008 Now, since m˜ (t) is bandlimited to W Hz, there is no need to j2πfct model the left component of Hbp(f + f ) = hbp(t)e− : c F{ } Hbp(f) Hbp(f + fc) H˜ (f) | | | | | | f f f fc fc 2fc 0 B 0 B − − − j2πfct Replacing hbp(t)e− with the complex-baseband response h˜(t) gives the “complex-baseband equivalent” signal path: m˜ (t) h˜(t) v˜s(t) The spectrums above show that h (t) = Re h˜(t) 2ej2πfct . -

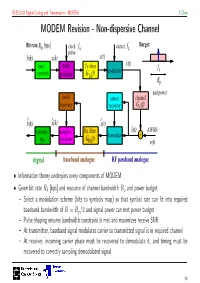

MODEM Revision

ELEC3203 Digital Coding and Transmission – MODEM S Chen MODEM Revision - Non-dispersive Channel Burget: Bit rate:Rb [bps] clock fs carrier fc pulse b(k) x(k) x(t) bits / pulse Tx filter s(t) modulator fc symbols generator GTx (f) Bp and power clock carrier channel recovery recovery G c (f) b(k)^ x(k)^ x(t)^ symbols / sampler / Rx filter s(t)^ AWGN demodulat + bits decision GRx (f) n(t) digital baseband analogue RF passband analogue • Information theory underpins every components of MODEM • Given bit rate Rb [bps] and resource of channel bandwidth Bp and power budget – Select a modulation scheme (bits to symbols map) so that symbol rate can fit into required baseband bandwidth of B = Bp/2 and signal power can met power budget – Pulse shaping ensures bandwidth constraint is met and maximizes receive SNR – At transmitter, baseband signal modulates carrier so transmitted signal is in required channel – At receiver, incoming carrier phase must be recovered to demodulate it, and timing must be recovered to correctly sampling demodulated signal 94 ELEC3203 Digital Coding and Transmission – MODEM S Chen MODEM Revision - Dispersive Channel • For dispersive channel, equaliser at receiver aims to make combined channel/equaliser a Nyquist system again + = bandwidth bandwidth channel equaliser combined – Design of equaliser is a trade off between eliminating ISI and not enhancing noise too much • Generic framework of adaptive equalisation with training and decision-directed modes n[k] x[k] y[k] f[k] x[k−k^ ] Σ equaliser decision d channel circuit − Σ -

IQ, Image Reject, & Single Sideband Mixer Primer

ICROWA M VE KI , R IN A C . M . S 1 H IQ, IMAGE REJECT 9 A 9 T T 1 E E R C I N N I G & single sideband S P S E R R E F I O R R R M A A B N E C Mixer Primer Input Isolated By: Doug Jorgesen introduction Double Sideband Available P Bandwidth Wireless communication and radar systems are under continuous pressure to reduce size, weight, and power while increasing dynamic range and bandwidth. The quest for higher performance in a smaller 1A) Double IF I R package motivates the use of IQ mixers: mixers that can simultaneously mix ‘in-phase’ and ‘quadrature’ Sided L P components (sometimes called complex mixers). System designers use IQ mixers to eliminate or relax the Upconversion ( ) ( ) f Filter Filtered requirements for filters, which are typically the largest and most expensive components in RF & microwave Sideband system designs. IQ mixers use phase manipulation to suppress signals instead of bulky, expensive filters. LO푎 푡@F푏LO1푡 FLO1 The goal of this application note is to introduce IQ, single sideband (SSB), and image reject (IR) mixers in both theory and practice. We will discuss basic applications, the concepts behind them, and practical Single Sideband considerations in their selection and use. While we will focus on passive diode mixers (of the type Marki Mixer I R sells), the concepts are generally applicable to all types of IQ mixers and modulators. P 0˚ L 1B) Single IF 0˚ P Sided Suppressed Upconversion I. What can an IQ mixer do for you? 90˚ Sideband ( ) ( ) f 90˚ We’ll start with a quick example of what a communication system looks like using a traditional mixer, a L I R F single sideband mixer (SSB), and an IQ mixer.