Peer Education Into a Pre-Existing Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving South Boston Rail Corridor Katerina Boukin

Improving South Boston Rail Corridor by Katerina Boukin B.Sc, Civil and Environmental Engineering Technion Institute of Technology ,2015 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2020 ○c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2020. All rights reserved. Author........................................................................... Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 19, 2020 Certified by. Andrew J. Whittle Professor Thesis Supervisor Certified by. Frederick P. Salvucci Research Associate, Center for Transportation and Logistics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by...................................................................... Colette L. Heald, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Chair, Graduate Program Committee 2 Improving South Boston Rail Corridor by Katerina Boukin Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 19, 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Civil and Environmental Engineering Abstract . Rail services in older cities such as Boston include an urban metro system with a mixture of light rail/trolley and heavy rail lines, and a network of commuter services emanating from termini in the city center. These legacy systems have grown incrementally over the past century and are struggling to serve the economic and population growth -

Massachusetts House of Representatives: Upgrading Greater Boston MBTA Rail System St

Massachusetts House of Representatives: Upgrading Greater Boston MBTA Rail System St. John’s Preparatory School - Danvers, Massachusetts - December 2020 Letter from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Brett Butler. I am a Senior at St. John’s Prep, and I will serve as your chair for the Massachusetts House of Representatives on Railway Service. I have been involved in Model UN at the Prep for 5 years. Outside of Model UN, I am on the SJP Tennis Team, an Eagles’ Wings Leader, a member of Spire Society, a member of the National Honor Society, and a member of the Chinese National Honor Society. The topic of Railway Service has really fascinated me, since my father is an executive in the FTA (Federal Transit Administration), which is part of the DOT (Department of Transportation), and he has been my inspiration for my research into this topic. Also, I am a frequent passenger on the “T” and Commuter Rail (as well as commuter rail and subway services in many different cities such as Washington D.C., Los Angeles, and Montreal). Thus, I recommend that you read through this paper as well as to do your own research on the frequency, extension, and public trust in the Greater Boston Railway Service. Please do not hesitate to email me with any questions or concerns! I will be happy to assist you, and I look forward to meeting you in December! Thank you, Brett Butler ‘21 ([email protected]) Chair, Massachusetts House of Representatives on Railway Service, SJPMUN XV Dear Delegates, My name is Brendan O’Friel. -

Federal Register

FEDERAL REGISTER Vol. 85 Monday, No. 22 February 3, 2020 Pages 5903–6022 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 18:50 Jan 31, 2020 Jkt 250001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\03FEWS.LOC 03FEWS lotter on DSKBCFDHB2PROD with FR_WS II Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 22 / Monday, February 3, 2020 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) Subscriptions: and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Government Publishing Office, is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Email [email protected] issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

South Florida RTA's Transit Development Plan

Prepared for: South Florida Regional Transportation Authority 800 NW 33rd Street, Suite 100 Pompano Beach, FL 33064 (954) 942‐7245 Prepared by: Tindale‐Oliver & Associates, Inc. 6750 N. Andrews Avenue, Suite 200 Fort Lauderdale, FL 33309 (954) 489‐2748 In cooperation with August 2013 (This page is intenƟonally leŌ blank) TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Section ES.1: INTRODUCTION ……… ............................................................................... ES‐1 ES.1.1 TDP Checklist ….. ................................................................................................................... ES‐2 Section ES.2: OVERVIEW OF SFRTA .............................................................................. ES‐3 ES.2.1 SFRTA Existing Services ......................................................................................................... ES‐3 ES.2.2 Accomplishments Since Last TDP Major Update ................................................................. ES‐6 Section ES.3: SUMMARY OF PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT ..................................................... ES‐9 ES.3.1 Tri‐Rail On‐Board Survey ...................................................................................................... ES‐9 ES.3.2 Intercept Survey .................................................................................................................... ES‐9 ES.3.3 Online Efforts …………… ......................................................................................................... ES‐10 ES.3.4 Meetings and Presentations -

Ocm04234782-1985.Pdf (4.189Mb)

al Report 1985 assachusetts Bay ansnortation Authority GOVDOC HEA491 .B75M3 1985 Table of Contents Letter from the 1 Highlights of 1985 2 What is the MBTA? 5 The MBTA in 1985 9 Service 15 Programs 21 Financial Statements 31 Cover: This huge sculpture by Toshihiro Katayama is at Alewife Station, opened on March 30, 1985, marking the completion of the $574 million north- west extension of the Red Line into North Cambridge and Somerville. The sta- tion, which includes a 2,000-car parking garage and 12-berth busway, serves as a major subway/bus/ auto transfer point. This report will examine the ways the MBTA continues to grow to serve significant increases in passenger demand. Governor Michael S. Dukakis' commitment to mass transportation, solid support by the State Legislature, the Advisory Board, and the enthusiasm, pride and professionalism of MBTA employees ensure continued progress in transforming the oldest transportation system in the nation into one of the most modern. Projections indicate that over the course of the next decade Boston's central business district will expand exponentially in commercial development and employment. By the year 2000, the downtown area will include an additional 17 million square feet of commercial space and 150,000 new workers. It is our goal to meet their transportation needs, and we have begun to face this challenge with innovation in 1985. We are expanding capacity, improving reliability and enhancing safety, while staying within our budget and making great strides in containing costs and increasing productivity. We look forward to playing an increasingly important role in the life of our region. -

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority Balance Sheet

li Report 1986 assachusetts Bay rtation Authority In 1986, the MBTA's aggressive vehicle acquisition and station modernization program continued to provide the facilities needed to meet the growing trans- portation needs of Bos- ton's rapidly increasing workforce. Construction and modernization pro- grams continue to allow the MBTA to prepare for the transportation needs required during construction of the Cen- tral Artery North Area Project (CAN A), the Central Artery and the Third Harbor Tunnel. Table of contents Letter from the General Manager Highlights of 1986 MBTA service 11 Equipment replacement and renovation Construction 23 Studies for future programs Programs 31 Financial statements Train operations are directed from the Authority's Central Con- trol center in downtown Boston. Pictured at right. General Manager James F. O'Leary (I) dis- cusses morning Orange Line rapid transit ser- vice with Director of Operations John K. Leary (r) and dispatcher Michael F. Devin (seated). itter from the sneral Manager Tremendous strides made by the MBTA during 1986 have brought us even closer toward realizing our goal of providing reliable, efficient and safe public transportation for the peo- ple of the Greater Boston region. Projects underway for the past few years are nearing completion. Ridership continues to grow. The economy maintains its strength. As the opening of new office buildings continues to accelerate the need for public transportation, the Authority is working to meet the needs of today and to prepare for the demands of tomorrow. This year, we have increased revenue miles of service on Orange and Blue rapid transit lines and trackless trolley, as well as on many bus routes. -

United States District Court District of Massachusetts

Case 1:11-cv-10103-GAO Document 68 Filed 09/08/14 Page 1 of 85 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS ANDREA GORDON, Plaintiff, V. CIVIL ACTION NO. 11-10103-GAO MASSACHUSETTS BAY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY and SCOTT ANDREWS, Defendants. REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION RE: THE DEFENDANTS’ MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT (DOCKET ENTRY # 33) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER RE: DEFENDANTS’ MOTION TO STRIKE (DOCKET ENTRY # 63) September 8, 2014 BOWLER, U.S.M.J. Pending before this court is a motion for summary judgment (Docket Entry # 33) filed by defendants Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (“the MBTA”) and Scott Andrews (“Andrews”) (collectively “defendants”). (Docket Entry # 33). Defendants also seek to strike certain portions of plaintiff’s response to their LR. 56.1 statement of undisputed facts and a number of exhibits plaintiffs filed to avoid summary judgment. (Docket Entry # 63). Plaintiff Andrea Gordon (“plaintiff”) opposes both motions. (Docket Entry ## 45, 65). After conducting a hearing on July 28, 2014, this court took the Case 1:11-cv-10103-GAO Document 68 Filed 09/08/14 Page 2 of 85 motions (Docket Entry ## 33, 63) under advisement. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND Plaintiff submits that the MBTA denied her a promotion in 2007 based on her race (African American) and gender and in retaliation for her testimony in a discrimination lawsuit filed by Johnny Junior (“Junior”), an MBTA employee, against the MBTA and her protected activities concerning another MBTA employee, Terrence Ward (“Ward”). (Docket Entry # 1, ¶ 31). In March 2008, Andrews, the MBTA employee awarded the promotion, purportedly subjected plaintiff to racist and hostile behavior during a staff meeting. -

Historic Context Report for Transit Rail System Development

Historic Context Report for Transit Rail System Development Nationwide, with localized contexts for the Boston, Chicago, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. metropolitan areas June 2017 Prepared for: The Federal Transit Administration Headquarters Washington, D.C. Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. i Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Objectives ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Organization of the Report ................................................................................................................. 2 2. National Context .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ -

Planning Transit Networks with Origin, Destination, And

Planning Transit Networks with Origin, Destination, and Interchange Inference by Catherine Vanderwaart B.A., Swarthmore College (2003) Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master in City Planning and Master of Science in Transportation at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2016 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2016. All rights reserved. Author . Department of Urban Studies and Planning Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering January 25, 2016 Certified by. John P. Attanucci Research Associate, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Certified by. Frederick P. Salvucci Senior Lecturer, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . P. Christopher Zegras Associate Professor Chair, MCP Committee, Department of Urban Studies and Planning Accepted by . Heidi M. Nepf Donald and Martha Harleman Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students 2 Planning Transit Networks with Origin, Destination, and Interchange Inference by Catherine Vanderwaart Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on January 25, 2016, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master in City Planning and Master of Science in Transportation Abstract The institutional and financial circumstances at many transit agencies significantly constrain the bus planning process. Long-term planning focuses -

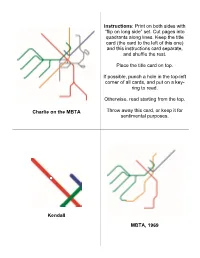

Charlie on the MBTA Instructions

Instructions: Print on both sides with “flip on long side” set. Cut pages into quadrants along lines. Keep the title card (the card to the left of this one) and this instructions card separate, and shuffle the rest. Place the title card on top. If possible, punch a hole in the top-left corner of all cards, and put on a key- ring to read. Otherwise, read starting from the top. Charlie on the MBTA Throw away this card, or keep it for sentimental purposes. Kendall MBTA, 1969 These are the times that try men’s souls. In the course of our nation’s history, the people of Boston have rallied bravely whenever the rights of men have been threatened. MBTA maps derived from the “Rapid Transit/Key Bus Routes Map” from the Today, a new crisis has arisen. The MBTA website. Metropolitan Transit Authority, better known as the MTA, is attempting to Information used to create historical levy a burdensome tax on the maps derived from “An Animated population in the form of a subway fare History of the MBTA” on increase. vanshnookenraggen.com. Citizens, hear me out, this could happen to you! “(Charlie on the) M.T.A.”, The Kingston Trio, 1949 “It seems to me, my love, that the terror of this new Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority grows “I saw Charlie this morning for the first stronger each year. It has only time in a few months. He was heading been around for five years, and it inbound from Kendall Square at the has already caused irreparable same time as I was.