ETHJ Vol-46 No-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

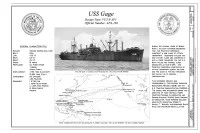

Design Type: VC2-S-AP5 Official Number: APA-168

USSGage Design Type: VC2-S-AP5 Official Number: APA-168 1- w u.. ~ 0 IJ) <( z t!) 0::: > GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS DURING THE CLOSING YEARS OF WORLD z~ WAR II, MILl T ARY PLANNERS REQUESTED ~ Q ~ w BUILDER: OREGON SHIPBUILDING CORP. THAT THE MARITIME COMMISSION <~ Q 0 "'~ <w BUlL T: 1944 CONSTRUCT A NEW CLASS OF ATTACK z w~ 11 Q ~ 0 LOA: 455'-0 TRANSPORTS. DESIGNERS UTILIZED THE w ~ 11 z BEAM: 62'-0 NEW VICTORY CLASS AND CONVERTED IT CX) "'u "~ 11 "'I- ~ -w ~ DRAFT: 24'-0 INTO A TROOP TRANSPORT FOR THE U.S. IW ~ ~ z <I~ 0 SPEED: 18 KNOTS NAVY CALLED THE HASKELL CLASS, ~ a._w z< ~ 0 <tffi u PROPULSION: OIL FIRED STEAM DESIGNATED AS VC2-S-AP5. THE w ~ w ~ z w~ iii TURBINE, MARITIME COMMISSION CONSTRUCTED 117 ~ zw ~ z t!)~ w SINGLE SHAFT ATTACK TRANSPORTS DURING THE WAR, <t~ 5 ~ t!)[fl w ~ DISPLACEMENT: 7,190 TONS (LIGHTSHIP) THE USS GAGE AT ANCHOR IN SAN FRANCISCO BAY, CIRCA 1946 PHOTO# NH98721 AND THE GAGE IS THE SOLE REMAINING l: u ~ 0 (/)~ ~ ~ (/) w 10,680 TONS (FULL) SHIP AFLOAT IN ITS ORIGINAL X ~ ::J ~ w • ~ CONFIGURATION. "u COMPLEMENT: 56 OFFICERS w ~ 9 ~ ~ ~ 480 ENLISTED Q w u ~ 11 .. 0 <:::. or;.·• ..,..""' 0 THIS RECORDING PROJECT WAS ~ ARMAMENT: I 5 /38 GUN w ' ~ ' Seattle, WA COSPONSORED BY THE HISTORIC AMERICAN ~ I 40MM QUAD MOUNT .. >- ' I- 4 40MM TWIN MOUNTS -~!',? _. -::.: -::; -:..: ~: :- /" Portland, OR ENGINEERING RECORD (HAER) AND THE 8 .~~ - -·- ----- --.. - It N z 10 20MM SINGLE -·- .- .-··-· -··- ·-. -· -::;;:::::-"···;:;=····- .. - .. _ .. ____ .. ____\_ U.S. MARITIME ADMINISTRATION (MARAD). ffi u - ...-··- ...~ .. -··- .. =·.-.=·... - .... - ·-·-····-.. ~ · an Francisco, CA :.:: > 1 MOUNTS 9 aJ!,. -

Neptune's Might: Amphibious Forces in Normandy

Neptune’s Might: Amphibious Forces in Normandy A Coast Guard LCVP landing craft crew prepares to take soldiers to Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944 Photo 26-G-2349. U.S. Coast Guard Photo, Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command By Michael Kern Program Assistant, National History Day 1 “The point was that we on the scene knew for sure that we could substitute machines for lives and that if we could plague and smother the enemy with an unbearable weight of machinery in the months to follow, hundreds of thousands of our young men whose expectancy of survival would otherwise have been small could someday walk again through their own front doors.” - Ernie Pyle, Brave Men 2 What is National History Day? National History Day is a non-profit organization which promotes history education for secondary and elementary education students. The program has grown into a national program since its humble beginnings in Cleveland, Ohio in 1974. Today over half a million students participate in National History Day each year, encouraged by thousands of dedicated teachers. Students select a historical topic related to a theme chosen each year. They conduct primary and secondary research on their chosen topic through libraries, archives, museums, historic sites, and interviews. Students analyze and interpret their sources before presenting their work in original papers, exhibits, documentaries, websites, or performances. Students enter their projects in contests held each spring at the local, state, and national level where they are evaluated by professional historians and educators. The program culminates in the Kenneth E. Behring National Contest, held on the campus of the University of Maryland at College Park each June. -

Marblehead in World War II, D-Day by Sean Casey

Draft Text © Sean M. Casey, not to be used without author’s consent Chapter 19: Overlord June 5-6, 1944 in Europe Yankees of the 116th In late 1940 President Roosevelt had activated all of the National Guard units in the country and brouGht them into the United States Army. These units served as the foundation upon which the war-size army would be built. Many of the units – of various sizes and shapes -- had a linaGe, and could trace their oriGins to state militia units from earlier wars. As units were brouGht into the army, and as the army Grew and orGanized itself in 1941 and 1942, the once-National Guard units were auGmented by draftees to brinG the units to full strenGth. Thus did William Haley find himself a member of the “Essex Troop” of the former New Jersey National Guard; and Daniel Lord found himself training alongside midwesterners as a member of the 84th Infantry Division, made up from parts of the Indiana and Illinois National Guard. But perhaps the quirkiest example of this phenomena is how five Marbleheaders – Yankees all – found themselves assiGned to the 116th Infantry ReGiment1 of the 29th Infantry Division.2 The 116th had been part of the Virginia National Guard, and 82 years before had been Stonewall Jackson’s BriGade in the Confederate Army. The five were: Ralph Messervey, Bill Hawkes, the Boggis Brothers, Porter and Clifford, and their cousin, Willard Fader. Ralph Messervey was 27 when he was drafted in early 1942. Stocky, with red hair, and an outgoing personality, he was known as “Freckles” to his friends and family. -

Battle of Mansfield Scenario Map Sabine Crossroads Section Pleasant Grove Section

The Federal vanguard deploys on top of Huneycutt Hill. Photo by Troy Turner. SCENARIO numerically and materially superior Northern armies and navies. In March 1864, a well-equipped Federal expeditionary force of over 30,000 troops was assembled in southeast Louisiana to ascend the Red River and seize Shrevesport. The joint army-navy BATTLE OF operation, including a flotilla of gunboats commanded by Navy Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, was placed under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks. Subordinate officers, MANSFIELD as well as Bank’s superiors far away in Washington DC, had little April 8, 1864 confidence in his abilities. His high rank was due to political connections, and he had no formal military training, which was quite evident in a lackluster performance up to this point. After Federal forces gained control of the Mississippi River There were other troubling problems from the start. Units were with the capture of Vicksburg in July 1863, the Confederacy drawn from four separate corps, who were unfamiliar at working was effectively split in two. Western Louisiana and eastern Texas with each other. The most experienced infantry, 10,000 combat however, had not yet suffered the ravages of war and remained veterans on loan from Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Army of a supply source for Confederate troops west of the Mississippi. the Tennessee, were expected to be returned by mid-April for the The small town of Shrevesport, located on the rust-colored Red upcoming Atlanta campaign. Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele, com- River in northwestern Louisiana, was strategically important manding another 10,000 Federal troops in Arkansas and in gar- for its armory, foundry, powder mill, and shipyard, and as the risons on the Indian Territory frontier, remained reluctant after headquarters for the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi. -

Appendix 1 Amphibious Ships and Craft

Appendix 1 Amphibious Ships and Craft Ships ADCS Air Defence Control Ship AKA Attack Cargo Ship APA Attack Transport ATD Amphibious Transport Dock CVHA Assault Helicopter Carrier (later LPH) LPD Amphibious Transport Dock LPH Assault Helicopter Carrier LSC Landing Ship, Carrier LSD Landing Ship, Dock LSE(LC) Landing Ship, Emergency Repair (Landing Craft) LSE(LS) Landing Ship, Emergency Repair (Landing Ship) LSF Landing Ship, Fighter Direction LSG Landing Ship, Gantry LSH Landing Ship, Headquarters LSH(C) Landing Ship, Headquarters (Command) LSI Landing Ship, Infantry LSL Landing Ship, Logistic LSM Landing Ship, Medium LSM(R) Landing Ship, Medium (Rocket) LSP Landing Ship, Personnel LSS Landing Ship, Stern Chute LSS(R) Landing Ship, Support (Rocket) LST Landing Ship, Tank LST(A) Landing Ship, Tank (Assault) LST(C) Landing Ship, Tank (Carrier) LST(D) Landing Ship, Tank (Dock) LST(Q) administrative support ship LSU Landing Ship, Utility LSV Landing Ship, Vehicle MS (LC) Maintenance Ship (Landing Craft) MS (LS) Maintenance Ship (Landing Ship) M/T Ship Motor Transport Ship W/T Ship Wireless Tender 212 Appendix 1 213 Barges, craft and amphibians DD Duplex Drive (amphibious tank) DUKW amphibious truck LBE Landing Barge, Emergency repair LBK Landing Barge, Kitchen LBO Landing Barge, Oiler LBV Landing Barge, Vehicle LBW Landing Barge, Water LCA Landing Craft, Assault LCA(HR) Landing Craft, Assault (Hedgerow) LCA(OC) Landing Craft, Assault (Obstacle Clearance) LCC Landing Craft, Control LCE Landing Craft, Emergency Repair LCF Landing Craft, Flak -

To Defend the Sacred Soil of Texas: Tom Green and the Texas Cavalry in the Red River Campaign

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 46 Issue 1 Article 7 3-2008 To Defend the Sacred Soil of Texas: Tom Green and the Texas Cavalry in the Red River Campaign Gary Joiner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Joiner, Gary (2008) "To Defend the Sacred Soil of Texas: Tom Green and the Texas Cavalry in the Red River Campaign," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 46 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol46/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIAI'ION 11 TO DEFEND THE SACRED SOIL OF TEXAS: TOM GREEN AND THE TEXAS CAVALRY IN THE RED RIVER CAMPAIGN by Gary Joiner In March I &64, Union forces began their fifth attempt to invade Texas in less than fifteen months. The commander of the Union Department of the Gulf, based in New Orleans, was Major General Nathaniel Prentiss Banks. With aspirations for the presidency, Banks was at that time arguably more pop ular than Abraham Lincoln. He needed a stunning, or at least a well publicized, victory to vault him into office. The Union Navy had failed at Galveston Bay on New Year's Day, 1863. 1 Banks' 19th Corps commander, Major General William Bud Franklin. -

Ship Hull Classification Codes

Ship Hull Classification Codes Warships USS Constitution, Maine, and Texas MSO Minesweeper, Ocean AKA Attack Cargo Ship MSS Minesweeper, Special (Device) APA Attack Transport PC Patrol Coastal APD High Speed Transport PCE Patrol Escort BB Battleship PCG Patrol Chaser Missile CA Gun Cruiser PCH Patrol Craft (Hydrofoil) CC Command Ship PF Patrol Frigate CG Guided Missile Cruiser PG Patrol Combatant CGN Guided Missile Cruiser (Nuclear Propulsion) PGG Patrol Gunboat (Missile) CL Light Cruiser PGH Patrol Gunboat (Hydrofoil) CLG Guided Missile Light Cruiser PHM Patrol Combatant Missile (Hydrofoil) CV Multipurpose Aircraft Carrier PTF Fast Patrol Craft CVA Attack Aircraft Carrier SS Submarine CVE Escort Aircraft Carrier SSAG Auxiliary Submarine CVHE Escort Helicopter Aircraft Carrier SSBN Ballistic Missile Submarine (Nuclear Powered) CVL Light Carrier SSG Guided Missile Submarine CVN Multipurpose Aircraft Carrier (Nuclear Propulsion) SSN Submarine (Nuclear Powered) CVS ASW Support Aircraft Carrier DD Destroyer DDG Guided Missile Destroyer DE Escort Ship DER Radar Picket Escort Ship DL Frigate EDDG Self Defense Test Ship FF Frigate FFG Guided Missile Frigate FFR Radar Picket Frigate FFT Frigate (Reserve Training) IX Unclassified Miscellaneous LCC Amphibious Command Ship LFR Inshore Fire Support Ship LHA Amphibious Assault Ship (General Purpose) LHD Amphibious Assault Ship (Multi-purpose) LKA Amphibious Cargo Ship LPA Amphibious Transport LPD Amphibious Transport Dock LPH Amphibious Assault Ship (Helicopter) LPR Amphibious Transport, Small LPSS Amphibious Transport Submarine LSD Dock Landing Ship LSM Medium Landing Ship LST Tank Landing Ship MCM Mine Countermeasure Ship MCS Mine Countermeasure Support Ship MHC Mine Hunter, Coastal MMD Mine Layer, Fast MSC Minesweeper, Coastal (Nonmagnetic) MSCO Minesweeper, Coastal (Old) MSF Minesweeper, Fleet Steel Hulled 10/17/03 Copyright (C) 2003. -

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents

Navy and Coast Guard Ships Associated with Service in Vietnam and Exposure to Herbicide Agents Background This ships list is intended to provide VA regional offices with a resource for determining whether a particular US Navy or Coast Guard Veteran of the Vietnam era is eligible for the presumption of Agent Orange herbicide exposure based on operations of the Veteran’s ship. According to 38 CFR § 3.307(a)(6)(iii), eligibility for the presumption of Agent Orange exposure requires that a Veteran’s military service involved “duty or visitation in the Republic of Vietnam” between January 9, 1962 and May 7, 1975. This includes service within the country of Vietnam itself or aboard a ship that operated on the inland waterways of Vietnam. However, this does not include service aboard a large ocean- going ship that operated only on the offshore waters of Vietnam, unless evidence shows that a Veteran went ashore. Inland waterways include rivers, canals, estuaries, and deltas. They do not include open deep-water bays and harbors such as those at Da Nang Harbor, Qui Nhon Bay Harbor, Nha Trang Harbor, Cam Ranh Bay Harbor, Vung Tau Harbor, or Ganh Rai Bay. These are considered to be part of the offshore waters of Vietnam because of their deep-water anchorage capabilities and open access to the South China Sea. In order to promote consistent application of the term “inland waterways”, VA has determined that Ganh Rai Bay and Qui Nhon Bay Harbor are no longer considered to be inland waterways, but rather are considered open water bays. -

Salvage Diary from 1 March – 1942 Through 15 November, 1943

Salvage Diary from 1 March – 1942 through 15 November, 1943 INDUSTRIAL DEPARTMENT WAR DIARY COLLECTION It is with deep gratitude to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in San Bruno, California for their kind permission in acquiring and referencing this document. Credit for the reproduction of all or part of its contents should reference NARA and the USS ARIZONA Memorial, National Park Service. Please contact Sharon Woods at the phone # / address below for acknowledgement guidelines. I would like to express my thanks to the Arizona Memorial Museum Association for making this project possible, and to the staff of the USS Arizona Memorial for their assistance and guidance. Invaluable assistance was provided by Stan Melman, who contributed most of the ship classifications, and Zack Anderson, who provided technical guidance and Adobe scans. Most of the Pacific Fleet Salvage that was conducted upon ships impacted by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor occurred within the above dates. The entire document will be soon be available through June, 1945 for viewing. This salvage diary can be searched by any full or partial keyword. The Diaries use an abbreviated series of acronyms, most of which are listed below. Their deciphering is work in progress. If you can provide assistance help “fill in the gaps,” please contact: AMMA Archival specialist Sharon Woods (808) 422-7048, or by mail: USS Arizona Memorial #1 Arizona Memorial Place Honolulu, HI 96818 Missing Dates: 1 Dec, 1941-28 Feb, 1942 (entire 3 months) 11 March, 1942 15 Jun -

AIR and LIQUID SYSTEMS CORP., CBS CORPORATION, and FOSTER WHEELER LLC, Petitioners, V

No. 17-1104 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States AIR AND LIQUID SYSTEMS CORP., CBS CORPORATION, AND FOSTER WHEELER LLC, Petitioners, v. ROBERTA G. DEVRIES, Administratrix of the Estate of John B. DeVries, Deceased, and Widow in her own right, Respondent. INGERSOLL RAND COMPANY, Petitioner, v. SHIRLEY MCAFEE, Executrix of the Estate of Kenneth McAfee, and Widow in her own right, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit JOINT APPENDIX (VOLUME I OF II) SHAY DVORETZKY RICHARD PHILLIPS MYERS Counsel of Record Counsel of Record JONES DAY PAUL, REICH & MYERS 51 Louisiana Ave NW 1608 Walnut Street, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20001 Philadelphia, PA 19103 Tel.: (202) 879-3939 Tel.: (215) 735-9200 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner Counsel for Respondents CBS Corporation Roberta G. DeVries and Shirley McAffee (Additional counsel listed on inside cover) PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED JANUARY 31, 2018 CERTIORARI GRANTED MAY 14, 2018 CARTER G. PHILLIPS Counsel of Record SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP 1501 K Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20005 Tel.: (202) 736-8270 [email protected] Counsel for Respondent General Electric Co. (continued from front cover) i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page VOLUME I Docket Entries, In re: Asbestos Products Liability Litigation (No. VI), No. 16-2669 (3d Cir.) ............................... 1 Docket Entries, In re: Asbestos Products Liability Litigation (No. VI), No. 16-2602 (3d Cir.) ............................... 3 Docket Entries, In re: Asbestos Products Liability Litigation (No. VI), No. 15-2667 (3d Cir.) ............................... 5 Docket Entries, In re: Asbestos Products Liability Litigation (No. -

Tom Green and the Texas Cavalry in the Red River Campaign Gary Joiner

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 46 | Issue 1 Article 7 3-2008 To Defend the Sacred Soil of Texas: Tom Green and the Texas Cavalry in the Red River Campaign Gary Joiner Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Joiner, Gary (2008) "To Defend the Sacred Soil of Texas: Tom Green and the Texas Cavalry in the Red River Campaign," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 46: Iss. 1, Article 7. Available at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol46/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIAI'ION 11 TO DEFEND THE SACRED SOIL OF TEXAS: TOM GREEN AND THE TEXAS CAVALRY IN THE RED RIVER CAMPAIGN by Gary Joiner In March I &64, Union forces began their fifth attempt to invade Texas in less than fifteen months. The commander of the Union Department of the Gulf, based in New Orleans, was Major General Nathaniel Prentiss Banks. With aspirations for the presidency, Banks was at that time arguably more pop ular than Abraham Lincoln. He needed a stunning, or at least a well publicized, victory to vault him into office. The Union Navy had failed at Galveston Bay on New Year's Day, 1863. 1 Banks' 19th Corps commander, Major General William Bud Franklin. -

JOURNAL M 3 Vego County Historical Society

JOURNAL m 3 vego County Historical Society 1973 JOURNAL 1973 OSWEGO COONTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY Thirty-fourth Annual Publication T / 4r (f« 7 / CLS Oswego County Historical Society Richardson-Bates House 135 East Third Street Oswego, New York 13126 Founded in 1896 OFFICERS Wallace F. Workmaster, President Mrs. Douglas Aldrich, Recording Secretary Donald S. Voorhies, Treasurer Vice Presidents John C. Birdlebough Dr. J. Edward McEvoy Mrs. Hugh Barclay Miss Dorothy Mott Mrs. Robert F. Carter Mrs. George Nesbitt Mrs. Charles Denman Roswell Park Mrs. Elmer Hibbard Francis T. Riley Dr. Luciano J. Iorizzo Frank Sayer Fred S. Johnston Dr. Sanford Sternlicht Board of Managers Richard Beyer Dr. W. Seward Salisbury Mrs. Clinton Breads Anthony M. Slosek Miss Alice Carnrite Frederick G. Winn STAFF William D. Wallace, Director Joan A. Workmaster, Registrar Mr. and Mrs. Paul F. Wesner, Caretakers Oswego, New York Beyer Offset Inc. 1974 n Contents Dedication v President's Message vi Articles "Bound by Duty:" Abolitionists in Mexico New York, 1830-1842 Judith Wellman 1 Some Glass Bottles of Oswego County and Their Contents Leigh A. Simpson 31 The Richardson-Bates House Linda A. Wesner 40 Constantia Industries: The Williams-Southwell Sawmill and the Constantia Iron Foundry Leonard J. Cooper, Sr. 51 Prohibition and the Corruption of Civil Authority in Oswego R. Bruce McBride, Jr. 62 The Oswego County Historical Society assumes no responsibility for the statements or opinions of the contributors of the Journal. ij?5S m wmsam .•;• A \ V *t &- * "^ -..3F ::,J * # & *~ Frances Breads iv ' L/BRARY Dedication Every once in a while the world is blessed by the presence of an unusual human being.