Costume in Carnival: Social Performance, Rank and Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Malta SHORT Pierre Sammut ARTICLEST he Influence of the - Knights of the Order THINK of St. John on Malta CULTURE Due to its geographical position at the cross- roads of the Mediterranean, Malta has wit- nessed many different influences. In Ancient times, it attracted the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginian and the Romans, then other con- querors including the Arabs, Normans, Ara- gonese and the Crusaders, the French and the British. But one of the most fascinating pe- riods of Maltese history remains to this very day the period governed by the Knights Hos- pitaller, better known as the Order of St. John, who governed the islands from 1530 to the end of the 18th century, when the French un- der Commander Napoleon Bonaparte took over Malta. Prehistoric Temples and Majestic Palaces from different periods are unique landmarks. The Knights in particular left their marks on vario- us aspects of Maltese culture, in particular the language, buildings and literature. Their period is often referred to as Malta's Golden Age, as a result of the architectural and artistic embel- lishment and as a result of advances in the overall health, education and prosperity of the local population. Music, literature, theatre as well as visual arts all flourished in this period, which also saw the foundation and develop- ment of many of the Renaissance and Baro- que towns and villages, palaces and gardens, tomy and Surgery was established by Grand the most notable being the capital city, Valletta, Master Fra Nicolau Cotoner I d'Olesa at the one of several built and fortified by the Sacra Infermeria in Valletta, in 1676. -

00001-2006 ( .Pdf )

Jan2006.qxd 1/5/06 12:16 PM Page 1 PRESORTED JANUARY 2006 STANDARD ® U.S. POSTAGE PAID MIAMI, FL PERMIT NO. 7315 Tel: (305) 238-2868 1-800-605-7516 [email protected] We cover your world Vol. 17 No. 2 [email protected] When America's largest mass tran- sit system was shut down for three consecu- tive days last month, it was Trinidadian Roger Toussaint who led the strike for more than 37,000 bus and subway employees, page 2. In just over a year, the Caribbean will host Cricket World Cup 2007, the one-day The trial of controversial game’s biggest spectacle. West Indies Jamaican Cricket Board President Ken Gordon cop Reneto Adams was (inset) believes the region, despite among the lingering problems such as the rising big stories coming out of crime rate and poor form of the West the Caribbean Indies team, is on track to put on a grand in 2005, another challenging year for the region as a whole, show for all the world to see, page 11. page 13. Reggae superstar Shaggy will be among the top enter- tainers scheduled to visit the Caribbean in 2006, a year jampacked with attractions which should appeal to homesters and prospective visitors to the region, page 17. INSIDE News . .2 Feature . .12 Arts/Entertainment . .17 Youth/Education . .21 Local . .7 Food . .14 Health . .18 Sport . .23 Viewpoint . .9 Tourism/Travel . .15 Business . .19 Region . .25 Jan2006.qxd 1/5/06 12:16 PM Page 2 2 CARIBBEAN TODAY January 2006 www.caribbeantoday.com NEWS Caribbean advocates condemn U.S. -

'Stemming Vice a Proposal for Hospitaller

Stemming Vice: A Proposal for Hospitaller Virtuous Living in Ancien Régime Malta Fig. 1 War games and the real thing: A rare contemporary manuscript map by Paolo Passionei showing the Christian naval victory at the battle of the Dardanelles on the 26th June 1656 over the Ottomans. The Order’s naval squadron is shown on the right, with its seven galleys carrying off eleven captured Muslim prizes. (Courtesy of the Biblioteca Angelica, Rome) Stemming Vice: A Proposal for Hospitaller Virtuous Living in Ancien Régime Malta 365 The regulation of the conduct of the various categories of members pertaining to the Hospitaller and Military Order of St John and residing in Malta constituted a major concern for much the entire period of that institution’s settlement on the Island. A more cosmopolitan society and greater interaction with the Maltese population following the Order’s transfer from Vittoriosa to Valletta in 1571 certainly contributed towards an accelerated transformation of its erstwhile convent mentality, reinforced through the practice of a segregated residence within a collachio.1 The ideal of the chaste warrior-monk - in so far as it proved to be the rule prior to the mid-sixteenth century - metamorphosed into one where military prowess was no longer balanced with an austere lifestyle, but increasingly with one where noble lineage, wealth and a resulting sense of self-confident superiority often made a mockery out of the prescribed vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Knights visited prostitutes, procured mistresses and in some occasions even ended up contracting clandestine marriages.2 Individual Grand Masters who attempted to stem the trend did so at their own peril, as the unprecedented events of 1581 and 1639 so clearly demonstrated. -

Carnival Parade Id-Defilé Forthcoming Events

CARNIVAL PARADE ID-DEFILÉ FORTHCOMING EVENTS Carnival is celebrated outdoors in the five days Il-Karnival huwa ċċelebrat fil-ħamest ijiem ta’ GĦANAFEST 10-12 June 2011 preceding Lent in a number of towns and villages qabel ir-Randan f’diversi bliet u rħula madwar The Malta Mediterranean Folk Music Festival is a fabulous 3-day event of around the Maltese Islands, mainly in Valletta, il-Gżejjer tagħna, l-aktar fil-Belt, il-Furjana Mediterranean folk music, including Maltese folksongs (għana), Maltese songwriters Floriana and Ghaxaq in Malta and Nadur in Gozo. u Ħal Għaxaq f’Malta u fin-Nadur, Għawdex. and folk ensembles, together with guest folk musicians from neighbouring The Valletta Carnival offers a colourful spectacle, Il-Karnival tal-Belt joffri spettaklu ta’ kuluri, Mediterranean countries. Għanafest also hosts a series of workshops on traditional and prizes are awarded for the best artistic dances, u premjijiet jingħataw għall-aħjar żifniet, kostumi, instruments and a special programme for children, and is complemented by traditional Maltese food and the marvelous surroundings of the Argotti Botanical costumes, floats and grotesque masks. karrijiet u maskeruni. Gardens in Floriana. Further information: www.maltafolkmusicfestival.org The Valletta Carnival is dominated by the L-akbar attrazzjoni tal-Karnival tal-Belt hija Carnival Parade or Defilé, which is led by l-Isfilata, jewid-Defilé tal-Karrijiet, MALTA JAZZ FESTIVAL 14-16 July 2011 the majestic King Carnival float which, for immexxi dejjem mill-Karru majjestuż Now in its 21st edition, the Malta Jazz Festival has a special place in Malta’s Cultural the past years, has been the work tar-Re tal-Karnival, li minn bosta snin Calendar, attracting great stars of the international jazz scene to Malta. -

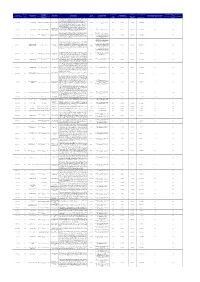

Project Ref. No. Nru Ta' Referenza Tal-Proġett Priority Axis Ass Prijoritarju Name of Beneficiaries Isem Il-Benefiċjarji Minis

Ministry (for Public Sector Co-financing Rate [European Regional Development Priority Axis Year of Allocation Operation End Date Amounts Committed*** Project Ref. No. Name of Beneficiaries Organisations) Name of Operation Project Description Postcode Category of Intervention Operation Start Date Total Amounts Paid at the End of the Operation € Fund] ** € Ass Sena tal- Data tat-Tmiem tal- Nru ta' Referenza tal-Proġett Isem il-Benefiċjarji Ministeru (għal Organizzazzjonijiet tas- Isem tal-Operazzjoni Deskrizzjoni tal-Proġett Kodiċi Postali Kategorija tal-Intervenzjoni Data tal-Bidu tal-Operazzjoni Ammonti Totali Mħallsa fi Tmiem l-Operazzjoni € Rata ta' Ko-finanzjament [Fond Ewropew għall-Iżvilupp Prijoritarju Allokazzjoni Operazzjoni Ammonti impenjati*** € Settur Pubbliku) Reġjonali] ** The Sustainable Living Complex comprises of research laboratories, design workshops and studios, academic and research staff offices, seminar and conference rooms, and lecture halls, with three targets. The primary objective is a model resource-efficient building, itself a "live laboratory" for monitoring a range of resource-efficient technologies in a real-life context, to provide a basis for policy-making on sustainable development issues, create an infrastructure for 058. Research and innovation infrastructure ERDF.01.122 PA1 The University of Malta Ministry for Education and Employment Sustainable Living Complex indigenous innovation in the construction industry, and provide a demonstration best-practice MSD 2080 2018 01/10/2017 31/12/2020 €30,000,000.00 n/a 80% (public) model. The second objective is state-of-the art research facilities for smart specialization areas, including resource-efficient building, aviation and aerospace technologies, and maritime studies. The third objective is to create a high-quality environment for inter-disciplinary research, exploiting potential synergies between the different disciplines present, creating a unique research eco- system of regional relevance. -

Heritage Malta (Hm) Annual Report 2014

HERITAGE MALTA (HM) ANNUAL REPORT 2014 CAPITAL WORKS An international design competition was launched to select the design for MUZA , involving the relocation of the National Museum of Fine Arts (NATIONAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS) from Admiralty House, South Street to the Auberge d’Italie, following which the chosen professional multi-disciplinary team was commissioned the project. An exhibition with all entries, incorporating also the newly-acquired Sciortino sculpture ‘Speed’, was set-up in October at the Auberge. This project is being proposed for ERDF funding. In the meantime preparations are underway for the necessary permits and tender documents. In collaboration with the Office of the Prime Minister, two design contests were launched to select the designs of national monuments for former Presidents Prof Guido de Marco and Dr Censu Tabone, Prime Minister Perit Dom Mintoff (Castille Square, Valletta), and an ‘ Artistic Statement to the Maltese Republic ’ (end of Republic Street, Valletta). The monuments for Prof Guido de Marco and Dr Censu Tabone were inaugurated in September and December in Valletta and St Julian’s respectively, whereas works are progressing well to complete the remaining monuments/artistic statement in 2015. Works also continued with the restoration of the main façade and the structural consolidation of the turrets of the Malta Maritime Museum . Restoration works also commenced in the loggia around the lower courtyard of the National Museum of Natural History in Mdina and on Bighi ’s historic smoking shed. Other works have been undertaken in other museums and sites. Among others, these include the installation of a CCTV system at the Ghar Dalam complex, and the continuation of the reconstruction work on Ta’ Kola Windmill , the final elements of which shall be installed in place in 2015. -

The Maltese Islands Calendar of Events 2017

THE MALTESE ISLANDS CALENDAR OF EVENTS 2017 -A DESTINATION FOR ALL SEASONS- Welcome from the Chief Executive, Malta Tourism Authority Dear Guest, the street band marches, the merrymaking and the religious activities connected with feasts of patron saints which every Malta is an island destination like no other. It is a holiday town and village honours yearly. Most feasts present their destination that makes you fall in love with it at first sight! firework displays in the evening skies for all to marvel at. Whether you want to experience some quality relaxation And as a bonus, most of the events are free of charge. time or else be active in exploring places of interest, you Moreover, it is possible for one to enjoy as many as three will be pleased to know that Malta has it all. Although it is different events on any given day, because distances are the smallest island state in the Mediterranean, Malta is also short and well connected by public transport. surprisingly full of entertaining, cultural and fun events all year round. There is no season during which the Maltese As our guest, you may rest assured that your visit will be islands take a break. complemented by an event that will match one or more of your preferences. Having chosen Malta as your destination, Most of the events that take place in Malta and Gozo are I augur that you enjoy your stay with us and that you will created by the Maltese, for the Maltese and foreigners return home with happy and fond memories. -

2018.0 Date of Approval of the Report by the 24-Jun-2019 Monitoring Committee

Annual implementation report for the Investment for growth and jobs goal PART A IDENTIFICATION OF THE ANNUAL IMPLEMENTATION REPORT CCI CCI Title Fostering a competitive and sustainable economy to meet our challenges Version 2018.0 Date of approval of the report by the 24-Jun-2019 monitoring committee EN1 EN IDENTIFICATION OF THE ANNUAL IMPLEMENTATION REPORT ......................................................................1 2. OVERVIEW OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE OPERATIONAL PROGRAMME (Article 50(2) and 111(3)(a) of Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013)..........................................................................................................................5 2.1. Key information on the implementation of the operational programme for the year concerned, including on financial instruments, with relation to the financial and indicator data. ...............................................................................5 3. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PRIORITY AXIS (Article 50(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013)..................8 3.1. Overview of the implementation ............................................................................................................................8 3.2. Common and programme specific indicators (Article 50(2) of Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013).......................14 Table 3A: Common and programme specific output indicators for the ERDF and the Cohesion Fund (by priority axis, investment priority, broken down by category of region for the ERDF) - PA 1 / 1a..........................................................14 -

THE MALTESE ISLANDS Malta - Gozo - Comino

THE MALTESE ISLANDS Malta - Gozo - Comino IN COLLABORATION WITH TOUR OPERATORS’ INFO MANUAL 2020 1 48 Tour Operators Handbook 2016 - 2017 Tour Operators Handbook 2016 - 2017 49 Images courtesy of the Malta Tourism Authority, photographer Malcolm Grima and the respective hotels. 2 Contents 4 Company Profile 5 Tour Operating and Leisure 6 MICE & Groups 8 English Language Courses 9 The Maltese Islands 10 Discover Diving 11 Gallery 13 Map 15 Traditional Maltese Cuisine 19 Events in Malta 27 Crafts of Malta 29 Accommodation 3 Company Profile Address: Established in 1982, Globalair Travel Ltd is a family owned company, built on the concept of Ewropa Business Centre, quality service and a friendly approach, under the chairmanship of Count Joseph A. Bugeja. Ground Floor, Dun Karm street, B’Kara Bypass, Birkirkara, BKR 9034, The company is one of the longest established and most respected in the travel industry in Malta Malta. It also enjoys an excellent reputation amongst its many partners worldwide. Tel: +356 2347 3000 Along the years, the company has built a strong dedicated and efficient multi-lingual staff are the E-mail: strategic partnership with a vast network of reliable key to our success. It is through their steady and [email protected] partners and thus enjoys excellent relationships with continuous endeavours that we have managed to Website: hoteliers, transport contractors, car rental companies, ensure that the preferences and requirements of our www.globalairtravel.com licensed guides, catering venues and other suppliers many clients are met. By walking that extra mile we all over the Maltese Islands. These strong links have have managed to exceed our clients’ expectations enabled the company to negotiate some of the most thus gaining the trust and loyalty of our many competitive rates available on the market. -

Read Now (PDF)

GOZO ❙ CONVERTED FARMHOUSE PORTOMASO ❙ PENTHOUSE MADLIENA ❙ MODERN DETACHED VILLA GĦARGĦUR ❙ DETACHED VILLA FOR SALE REF Nº 2991 P.O.R. FOR SALE REF Nº 2601 P.O.R. FOR SALE REF Nº 2004 Price: €4,590,000 FOR SALE REF Nº 2783 Price: €5,300,000 Panoramic Views ❙ 1,000 sqm - spread over three levels ❙ 6 bedrooms, Marina and open sea views ❙ 6 large bedrooms, 5 en-suite ❙ Outdoor Built on a plot measuring 971 sqm ❙ Sea and valley views. ❙ 5 double Valley and sea views. ❙ Set within approx 3,000sqm of land. ❙ 2000sqm 3 bathrooms ❙ Outdoor entertaining area with swimming pool and terrace ❙ This 675sqm property could be split into 2 separate penthouses bedrooms, 6 bathrooms ❙ Sun terraces, garden and swimming pool ❙ garden with kitchen/dining area, fireplace, infinity pool, music system, terrace ❙ Large open courtyard, stables and a paddock ❙ Also included is an underlying 2 car spaces accessed by lift. Heated indoor swimming pool, gym, wine cellar ❙ Double garage and Jacuzzi ❙ 4 bedrooms, 5 bathrooms ❙ 2 lock-up garages for up to 4 3 separate parking spaces cars and external parking. PENDER GARDENS ❙ DUPLEX APARTMENT TIGNE POINT ❙ APARTMENT PORTOMASO ❙ APARTMENT TA’ XBIEX ❙ PENTHOUSE FOR SALE REF Nº 2956 Price: €1,300,000 FOR SALE REF Nº 2770 Price: €2,500,000 FOR SALE REF Nº 2969 Price: €2,300,000 FOR SALE REF Nº 2723 Price: €3,400,000 286 sqm DUPLEX APARTMENT in a Special Designated Area ❙ Sea-views ❙ Enjoys access to a communal swimming pool ❙ Measuring Forming part of the Portomaso Laguna development ❙ Open plan Luxurious seafront PENTHOUSE ❙ Large terrace with a private 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms ❙ 2 terraces enjoying distant sea views ❙ approx. -

BOOK REVIEWS , Harrison Smith, Bri'tain in Malta

BOOK REVIEWS , Harrison Smith, Bri'tain in Malta. 2v. Malta, Progress Press, 1953. The two volumes on Britain in Malta by last year's Fulbright Lecturer in History at the Royal University of Malta form a major contribution to the study of 19th Century Malta. Since the War there has been a growing awareness that the best way of filling in the gaps of Maltese History is! to specialise in one particular period or aspect. Archi tecture and Emigration, to mention two specialised topics, have engaged the attention of students whose publications will continue to be considered as standard works for many years to come. The study of 19th Century political and constitutional history bristles with difficulties and writers before Harrison Smith had only attempted to treat the subject sketchily in general works, such as Laferla in Briti.~h Malta (2v.). Professor Harrison Smith brought a trained mind to bear on the various aspects of this important subject, and his researches have added considerably to our knowledge of what so far has been the bet~ noire of Maltese historians. Both volumes were prepared as theses, and the presentation of the subject matter suffers from too many quotations and reproduction of lengthy extracts that make the book difficult to dig-est.' Volume I, which treats of "Constitutional Development of J~lalta in the Nineteenth Century", "was originally prepared as a dissertation in partial fulfil ment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Georg-etown University", while Volume II, dealing with Italian Influence on British Policy in Malta lS99-1903 was a "these presentee a la Faculte des Lettres de I'Univer sit.e de Fribourg (Suisse) pour obtenir Ie grade de docteur". -

July 2009 No

C A R I B B E A N On-line C MPASS JULY 2009 NO. 16666 TheThe Caribbean’sC Monthly Look at Sea & Shore WEST INDIES REGATTA See story on page 12 JUSTIN SIHERA JULY 2009 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 JULY 2009 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 3 CALENDAR JULY 1 Public holiday in Antigua (Vere Bird Sr. Day) and Suriname (Eid-ul-Fitr) 2 Curaçao Flag Day. Public holiday in Curaçao 3 Emancipation Day. Public holiday in USVI The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore 3 - 4 17th Annual Firecracker 500 Race, Tortola, BVI. West End Yacht Club www.caribbeancompass.com (WEYC), Tortola, BVI, tel (284) 495-1002, fax (284) 495-4184, [email protected], www.weyc.net JULY 2009 • NUMBER 166 4 Independence Day (USA). Public holiday in Puerto Rico and USVI. Carnival in St. John, USVI 6 Public holiday in Cayman Islands (Constitution Day) and Guyana Trini Time! (Emancipation Day) 10 fun things to do ...............20 6 – 7 St. Vincent Carnival (Vincy Mas). Public holiday in St. Vincent SUZANNE AUSTIN & the Grenadines. www.carnivalsvg.com ELLEN SANPERE 7 FULL MOON 10 Independence Day. Public holiday in The Bahamas 10 - 12 Premier’s Cup Youth Regatta, Tortola. Royal British Virgin Islands Yacht Club (RBVIYC), tel (284) 494-3286, [email protected], www.rbviyc.net 11 Bequia’s 14th Annual Fisherman’s Day, [email protected] 11 – 19 Calabash Festival, Montserrat. www.visitmontserrat.com ‘Reef Jam ’09’ 11 - Aug 1 Cruzans party for coral ........ 10 Tobago Heritage Festival. Tel (868) 639-4441 14 Bastille Day. Public holiday in French West Indies 18 Volcano Anniversary.