The Story of Malta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malta and Gozo - Experiences of a Study Tour from 14Th to 21St September 2019 Text and Photos: Hans-Rudolf Neumann

Malta and Gozo - Experiences of a study tour from 14th to 21st September 2019 Text and Photos: Hans-Rudolf Neumann Saturday, 14th September 2019 The morning flight from Berlin via Frankfurt Main to Malta with Lufthansa ran without any incidents. But check-in service in Berlin leaves a lot to be desired; the transition to digital full automation to reduce staff provoked the oppo- site effect. Luggage check-in and boarding on two different ends of the airport caused anno- yance, while during boarding two flights were serviced on the same counter. One two Warsaw and one to Frankfurt Main – the line on luggage security was more than 200 people and it was safe to ask the pilot again if this is the right plane when entering the plane. The on-board meal on the flight to Frankfurt consisted of a 30 g al- mond tartlet of a 65 mm size and a drink, on the connecting flight to Malta we had a honey nut bar and another drink. Regarding that you had to leave the house at 4.45 am and entered the hotel in Malta around 12.40 pm, it was a re- Fig. 01: First group photo on the first day of the ex- markable performance, particularly as there was cursion: an INTERFEST study group with their no time to buy additional food in Frankfurt due wives and guests at the foot of the St. Michael bas- to the short connection time. There were better tion of the landfront in La Valletta under the um- times! Anyways, the dinner together at Hotel brella of the European cultural route FORTE CUL- Bay View in Sliema offered a rich buffet inclu- TURA®. -

Sample Chapter

Copyrighted material – 9781137524447 Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Notes on Contributors viii Preface xii Abbreviations xiv 1 Maritime Quarantine: Linking Old World and New World Histories 1 Alison Bashford Part I: Quarantine Histories in Time and Place 13 2 The Places and Spaces of Early Modern Quarantine 15 Jane Stevens Crawshaw 3 Early Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean Quarantine as a European System 35 Alexander Chase-Levenson 4 Incarceration and Resistance in a Red Sea Lazaretto, 1880–1930 54 Saurabh Mishra 5 Spaces of Quarantine in Colonial Hong Kong 66 Robert Peckham 6 Quarantine in the Dutch East Indies 85 Hans Pols 7 The Empire of Medical Investigation on Angel Island, California 103 Nayan Shah 8 Quarantine for Venereal Disease: New Zealand 1915–1918 121 Barbara Brookes 9 Influenza and Quarantine in Samoa 136 Ryan McLane v Copyrighted material – 9781137524447 Copyrighted material – 9781137524447 vi Contents 10 Yellow Fever, Quarantine and the Jet Age in India: Extremely Far, Incredibly Close 154 Kavita Sivaramakrishnan Part II: Heritage: Memorialising Landscapes of Quarantine 173 11 Sydney’s Landscape of Quarantine 175 Anne Clarke, Ursula K. Frederick, Peter Hobbins 12 Sana Ducos: The Last Leprosarium in New Caledonia 195 Ingrid Sykes 13 History, Testimony and the Afterlife of Quarantine: The National Hansen’s Disease Museum of Japan 210 Susan L. Burns 14 Citizenship and Quarantine at Ellis Island and Angel Island: The Seduction of Interruption 230 Gareth Hoskins Afterword 251 Mark Harrison Notes 258 Index 323 Copyrighted material – 9781137524447 Copyrighted material – 9781137524447 1 Maritime Quarantine: Linking Old World and New World Histories Alison Bashford From the early modern period, a global archipelago of quarantine stations came to connect the world’s oceans. -

Ghar Lapsi, Wied Iz-Zurrieq, U Filfla.Pdf

It-Toponomastika ta' Malta: stess jidher sew l-effett ta' dan iċ tliet fetħiet u jgħidulu Bieb il ċaqliq. L-ewwelnett iI-blat huwa Għerien; qiegħed sewwasew mat nċanat qisu rħama minħabba t tarf espost tal-Ponta s-Sewda tħaxkin taż-żewġ naħat tal-qasma (inkella r-Ras is-Sewda jew Il GĦAR LAPSI, (fault) kontra xulxin, u t-tieninett il Ħaġra s-Sewda). FI-istess inħawi, qortin imseBaħ l/-Gżira (man-naħa sa Żmien il-Kavallieri kien hawn ta' Lapsi) tniżżel b'mod li s-saff tal posta tal-għassa msejħa il-"Guardia WIED IŻ· qawwi ta' fuq qiegħed bi dritt iż tal-Gżira". Minn hawn, l-irdum jikser żonqor tan-naħa l-oħra (Ta' fdaqqa lejn il-lvant sa ma jintemm Bel/ula), meta dawn soltu ssibhom f L-lIsna, tliet ponot żgħar max-xatt ŻURRIEQ, f livelli ferm differenti. L-istess isimhom magħhom. Maqtugħ 'il qasma tkompli anke fuq in-naħa l barra bi dritt 1-lIsna hemm skoll U FILFLA oħra tat-triq, fejn tispikka bħala baxx mal-baħar- Ġanni l-Iswed tarġa qawwija bejn ix-Xagħra ta' jew Il-Blata ta' Ġanni l-Iswed. Għar Lapsi u l-art għolja li tittawwal għal fuqha. L-istess tarġa tkompli Ftit 'iI bogħod jinsab Il-Wied ta' l Alex Camilleri tul il-kosta kollha sa l-Imnajdra, IIsna, wied baxx imma kemmxejn peress li x-xtut t'hawnhekk huma twil li jibda minn ħdejn Ix-Xaqqa u lkoll parti mis-"sistema tal sa ma jasal biex jiżbokka hawn, Billi l-gżira ta' Malta hija Magħlaq", medda ta' art li tniżżlet jaqsam l-inħawi ta' Lapsi fżewġ taqsimiet ewlenin: lx-Xagħra tal mxaqilba sew mill-Ibiċ għall għal mal-baħar permezz ta' proċess tettoniku qisu terremot kbir iżda bil Gżira bejnu u s-Sies l-Abjad, u x grigal, id-dawra sħiħa minn mod, mifrux fuq bosta sekli minflok Xagħra ta' Għar Lapsi (li fnofsha Bengħisa sa Fomm ir-Riħ hi fdaqqa. -

PDF Download Malta, 1565

MALTA, 1565: LAST BATTLE OF THE CRUSADES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Pickles,Christa Hook,David Chandler | 96 pages | 15 Jan 1998 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781855326033 | English | Osprey, United Kingdom Malta, 1565: Last Battle of the Crusades PDF Book Yet the defenders held out, all the while waiting for news of the arrival of a relief force promised by Philip II of Spain. After arriving in May, Dragut set up new batteries to imperil the ferry lifeline. Qwestbooks Philadelphia, PA, U. Both were advised by the yearold Dragut, the most famous pirate of his age and a highly skilled commander. Elmo, allowing Piyale to anchor his fleet in Marsamxett, the siege of Fort St. From the Publisher : Highly visual guides to history's greatest conflicts, detailing the command strategies, tactics, and experiences of the opposing forces throughout each campaign, and concluding with a guide to the battlefields today. Meanwhile, the Spaniards continued to prey on Turkish shipping. Tim Pickles describes how despite constant pounding by the massive Turkish guns and heavy casualties, the Knights managed to hold out. Michael across a floating bridge, with the result that Malta was saved for the day. Michael, first with the help of a manta similar to a Testudo formation , a small siege engine covered with shields, then by use of a full-blown siege tower. To cart. In a nutshell: The siege of Malta The four-month Siege of Malta was one of the bitterest conflicts of the 16th century. Customer service is our top priority!. Byzantium at War. Tim Pickles' account of the siege is extremely interesting and readable - an excellent book. -

French Invasion of Malta

FRENCH INVASION OF MALTA On 10 June, the French assaulted four locations simultaneously: Jean Urbain Fugière and Jean Reynier directed the assault on 1 Gozo. They landed at Irdum il-Kbir and notwithstanding the Gozitan’s fierce offensive, the Citadel, Fort Chambray and the other fortifications were in French hands by nightfall. Onwards to Malta Louis Baraguey d’Hilliers headed the landing in St Paul’s Bay. The Maltese By early 1798, the French Republic controlled most of offered some resistance but were quickly overtaken. The French central Europe. The only European kingdom that advanced to capture all the fortifications in northern Malta. challenged its supremacy was Great Britain, but the 2 French were unable to mount a direct confrontation. The British Navy guarding the English Channel was practically impenetrable and the only way to bring Great Britain down to its knees was to disrupt the trade route, via Egypt, to the economically vital colony of India. The command of this campaign was assigned to Napoleon Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois directed the landing at St Julian’s. Bonaparte who assembled over 40,000 soldiers and a huge The Order deployed some vessels to attempt a pushback, but the French 3 succeeded to land six battalions. Likewise, the defenders stationed in the fleet in the port city of Toulon. They set sail on 19 May and Desaix and de Vaubois’ men marched respective strongholds retreated to Valletta. headed to Malta before proceeding to Egypt. Control of towards Valletta and the Three Cities. The Malta ensured dominance in the central Mediterranean. -

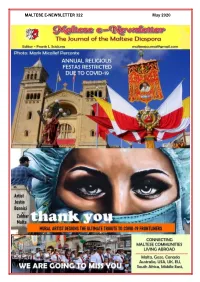

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020 French Occupation of Malta Malta and all of its resources over to the French in exchange for estates and pensions in France for himself and his knights. Bonaparte then established a French garrison on the islands, leaving 4,000 men under Vaubois while he and the rest of the expeditionary force sailed eastwards for Alexandria on 19 June. REFORMS During Napoleon's short stay in Malta, he stayed in Palazzo Parisio in Valletta (currently used as the Ministry for Foreign Affairs). He implemented a number of reforms which were The French occupation of The Grandmaster Ferdinand von based on the principles of the Malta lasted from 1798 to 1800. It Hompesch zu Bolheim, refused French Revolution. These reforms was established when the Order Bonaparte's demand that his could be divided into four main of Saint John surrendered entire convoy be allowed to enter categories: to Napoleon Bonaparte following Valletta and take on supplies, the French landing in June 1798. insisting that Malta's neutrality SOCIAL meant that only two ships could The people of Malta were granted FRENCH INVASION OF MALTA enter at a time. equality before the law, and they On 19 May 1798, a French fleet On receiving this reply, Bonaparte were regarded as French citizens. sailed from Toulon, escorting an immediately ordered his fleet to The Maltese nobility was expeditionary force of over bombard Valletta and, on 11 June, abolished, and slaves were freed. 30,000 men under General Louis Baraguey Freedom of speech and the press General Napoleon Bonaparte. -

"Mediterranean Under Quarantine", Malta 7-8 November 2014

H-Sci-Med-Tech Conference: "Mediterranean under Quarantine", Malta 7-8 November 2014 Discussion published by Javier Martinez-Antonio on Wednesday, October 29, 2014 Dear all, this is the programme of the international conference "Mediterranean Under Quarantine", the 1st International conference of the Quarantine Studies Network. 7- 8 November 2014. Hosted by the Mediterranean Institute University Of Malta. Old University Campus, Valletta. Friday, 7 November 9.00 – 9.30 : Registration - Aula Magna - Old University Building. 9.30: Opening Address : John Chircop, Director, Mediterranean Institute (UOM) ; International Quarantine Studies Network. 1st Session: Quarantine Geopolitics and Diplomacy (First Part: 9.50 – 11.30 hrs) Chair: Francisco Javier Martinez-Antonio Alison Bashford (University of Cambridge), Quarantine and Oceanic Histories: reflections on the old world and the new. Alexander Chase-Levenson (Princeton University), Quarantine, Cooperation, and Antagonism in the Napoleonic Mediterranean. Raffaella Salvemini (CNR, Italian National Research Council; ISSM, Institute of Studies on Mediterranean Societies), Quarantine in the ports of southern Italy: from local history to global history (18th-19th centuries). Ibrahim Muhammed al-Saadaoui (Université de Tunisie), Quarantaine et Crise diplomatique en Méditerranée: L’affaire de 1789 et la guerre entre Venise et la Régence de Tunis. 11.30 – 11.50: Coffee break (Second Part: 11.50 – 13.30 hrs) Chair: Quim Bonastra Dominique Bon (LAPCOS, Laboratoire d’Anthropologie et de Psycholgie Cognitives et Sociales, Université de Nice – Sophia Antipolis), La fin des quarantaines de santé dans la Province de Nice (1854). Daniela Hettstedt (Basel Graduate School of History, University of Basel), About Lighthouse, Abattoir and Epidemic Prevention. Global History Perspectives on the Internationalism in the Citation: Javier Martinez-Antonio. -

Download Download

Malta SHORT Pierre Sammut ARTICLEST he Influence of the - Knights of the Order THINK of St. John on Malta CULTURE Due to its geographical position at the cross- roads of the Mediterranean, Malta has wit- nessed many different influences. In Ancient times, it attracted the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginian and the Romans, then other con- querors including the Arabs, Normans, Ara- gonese and the Crusaders, the French and the British. But one of the most fascinating pe- riods of Maltese history remains to this very day the period governed by the Knights Hos- pitaller, better known as the Order of St. John, who governed the islands from 1530 to the end of the 18th century, when the French un- der Commander Napoleon Bonaparte took over Malta. Prehistoric Temples and Majestic Palaces from different periods are unique landmarks. The Knights in particular left their marks on vario- us aspects of Maltese culture, in particular the language, buildings and literature. Their period is often referred to as Malta's Golden Age, as a result of the architectural and artistic embel- lishment and as a result of advances in the overall health, education and prosperity of the local population. Music, literature, theatre as well as visual arts all flourished in this period, which also saw the foundation and develop- ment of many of the Renaissance and Baro- que towns and villages, palaces and gardens, tomy and Surgery was established by Grand the most notable being the capital city, Valletta, Master Fra Nicolau Cotoner I d'Olesa at the one of several built and fortified by the Sacra Infermeria in Valletta, in 1676. -

L-Inhawi Tal-Buskett U Tal-Girgenti Annex

L-In ħawi tal- Buskett u tal - Girgenti Annex Ww wwww.natura2000malta.org.mt Natura 2000 Management Plan ANNEX 1 MANAGEMENT PLAN DEVE LOPMENT 4 A.1.1 Summary of Methodology 4 A.1.2 Data Collection 5 A.1.3 Formulation of Management Objectives 6 A.1.4 Formulation of Management Actions 7 A.1.5 Work Plan Structure and Reporting and Review Plan 7 ANNEX 2 RELEVANT PLANNING PO LICIES 8 A.2.1 Structure Plan and Local Plan Policies 8 A.2.2 Conservation Order 28 ANNEX 3 ASSESSMENT METHODOLO GY OF CONSERVATION STATUS 29 ANNEX 4 SPECIFICATIONS OF MA NAGEMENT ACTIONS 37 A.4.1 Guidelines for Standard Monitoring Plans for Annex I Habitats and Annex II Species of the Habitats Directive and Annex I Species of the Birds Directive 37 A.4.2 Guidelines for the Elaboration of National Species Action Plans 43 A.4.3 Guidelines for Habitat Restoration Actions 46 P7. Application of access control measures at habitats 5230 and 92A0 46 P8. Planning and implementation of an IAS species control / eradication programme 47 P9. Planning and implementation of a pilot project for the expansion of habitat 9320: Olea and Ceratonia forests 50 A.4.4 Guidelines for the Signposting and Site promotion 54 A.4.5 Patrolling Schedule 58 ANNEX 5 COST RECOVERY MECHAN ISMS 71 A.5.1 Revenue Generating and Self -financing Opportunities 71 A.5.2 Funding Opportunities 74 ANNEX 6 MAPS 77 A.6.1 Boundary Map 78 A.6.2 Hydrology Map 79 A.6.3 Geology Map 80 A.6.4 Cultural Heritage Map 81 A.6.5 Land Use Map 82 A.6.6 Habitats Map 83 A.6.7 Signage Map 84 A.6.8 Land Ownership Map 85 A.6.9 Visitor Access Map 86 A.6.10 Actions Map 87 ANNEX BIBLIOGRAPHY 88 Tables Table A-1: Structure Plan policies; L -inħawi tal-Buskett u tal-Girgenti ............................... -

Comments on Qrendi's History by Dr

10 Snin Sezzjoni Zgflazagfl Comments on Qrendi's History by Dr. A.N. Welsh The last Ice Age reached its peak at about 20,000 then subsided, started to rise again last year. In about BC, and at that time the world was a very cold and dry 1500 BC 86 square kilometres of the Greek Island of place - dry because an enormous amount of the world's Santorini, an area larger than Gozo, disappeared for water lay frozen at the Poles, a layer of ice up to two ever in a volcano eruption. or three miles thick in places. This layer of ice extended We do not know exactly what happened here, down to the north of Italy, but not to Malta. People knowledge which awaits underwater archaeology and like ourselves were living where it was possible, in geological techniques, but we are running into the small bands, hunting what animals they could find, Temple Period, when we know that people were and foraging for edible plants and fruit. This meant farming in Malta (c .5400 BC) and as there are the covering large areas and so these 'hunter-gatherers' foundations of a wall dating to that time we can assume were nomads; they had no permanent settlement. From that there was some building going on. You will analysis of skeletons found they seem to have been appreciate that Malta and Gozo are small parts of higher undernourished, suffering periods of hunger, reaching ground which became isolated as the level of the about five feet in height and living to fifty if they were Mediterranean rose. -

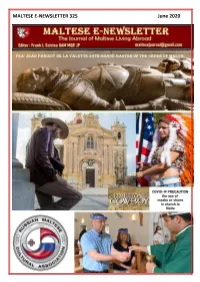

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 325 June 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 325 June 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 325 June 2020 Our prayer is that our lips will be an instrument of love and never of betrayal The spirit in your bread, fire in your wine. Some beauty grew up on our lips' for our lips are beloved not only because they express love in the intimacy of love loved ones but because also through them we are trailed by the Body and blood of Jesus. Today we are also recalling the generous blood Mass in the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of donation with which we assure healing and life Christ (Corpus Christi) to so many people. How beautiful it is to Homily of Archbishop Charles Jude Scicluna celebrate this generosity, so many people who We have made a three-month fasting and today in our donate their blood on the day of the Eucharist. parishes and churches the community can begin to Unless in the Gospel we have heard Jesus insists meet again to hear the Word of God and receive the in the need to come unto Him, eat His Body, drink Eucharist. His Blood to have life. Our prayer is that our lips We need to do this in a particular context that requires are an instrument of love and never of betrayal – a lot of restrictions so that this meeting of love does not as they were for Judas – and receive with a yellow lead us to the illnesses that brings death but keeps heart the Lord's Beloved Body and Blood. -

Flora Mediterranea 26

FLORA MEDITERRANEA 26 Published under the auspices of OPTIMA by the Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum Palermo – 2016 FLORA MEDITERRANEA Edited on behalf of the International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo by Francesco M. Raimondo, Werner Greuter & Gianniantonio Domina Editorial board G. Domina (Palermo), F. Garbari (Pisa), W. Greuter (Berlin), S. L. Jury (Reading), G. Kamari (Patras), P. Mazzola (Palermo), S. Pignatti (Roma), F. M. Raimondo (Palermo), C. Salmeri (Palermo), B. Valdés (Sevilla), G. Venturella (Palermo). Advisory Committee P. V. Arrigoni (Firenze) P. Küpfer (Neuchatel) H. M. Burdet (Genève) J. Mathez (Montpellier) A. Carapezza (Palermo) G. Moggi (Firenze) C. D. K. Cook (Zurich) E. Nardi (Firenze) R. Courtecuisse (Lille) P. L. Nimis (Trieste) V. Demoulin (Liège) D. Phitos (Patras) F. Ehrendorfer (Wien) L. Poldini (Trieste) M. Erben (Munchen) R. M. Ros Espín (Murcia) G. Giaccone (Catania) A. Strid (Copenhagen) V. H. Heywood (Reading) B. Zimmer (Berlin) Editorial Office Editorial assistance: A. M. Mannino Editorial secretariat: V. Spadaro & P. Campisi Layout & Tecnical editing: E. Di Gristina & F. La Sorte Design: V. Magro & L. C. Raimondo Redazione di "Flora Mediterranea" Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum, Università di Palermo Via Lincoln, 2 I-90133 Palermo, Italy [email protected] Printed by Luxograph s.r.l., Piazza Bartolomeo da Messina, 2/E - Palermo Registration at Tribunale di Palermo, no. 27 of 12 July 1991 ISSN: 1120-4052 printed, 2240-4538 online DOI: 10.7320/FlMedit26.001 Copyright © by International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo, Palermo Contents V. Hugonnot & L. Chavoutier: A modern record of one of the rarest European mosses, Ptychomitrium incurvum (Ptychomitriaceae), in Eastern Pyrenees, France . 5 P. Chène, M.