DOCUMENT RESUME Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Crash- Amundo

Stress Free - The Sentinel Sedation Dentistry George Blashford, DMD tvweek 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com January 19 - 25, 2019 Don Cheadle and Andrew Crash- Rannells star in “Black Monday” amundo COVER STORY .................................................................................................................2 VIDEO RELEASES .............................................................................................................9 CROSSWORD ..................................................................................................................3 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ....................................................................................................12 SPORTS.........................................................................................................................4 SUDOKU .....................................................................................................................13 FEATURE STORY ...............................................................................................................5 WORD SEARCH / CABLE GUIDE .........................................................................................19 READY FOR A LIFT? Facelift | Neck Lift | Brow Lift | Eyelid Lift | Fractional Skin Resurfacing PicoSure® Skin Treatments | Volumizers | Botox® Surgical and non-surgical options to achieve natural and desired results! Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Deborah M. Farrell, M.D. www.Since1853.com MODEL Fredricksen Outpatient Center, 630 -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. in Re

Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 12/29/2017 03:37:55 PM EST Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF THE MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS VOLUME I OF II WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS Gregory O. Olaniran D.C. Bar No. 455784 Lucy Holmes Plovnick D.C. Bar No. 488752 Alesha M. Dominique D.C. Bar No. 990311 Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1818 N Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 355-7917 (Telephone) (202) 355-7887 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for MPAA-Represented Program Suppliers December 29, 2017 Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS FOR 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS The Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (“MPAA”), its member companies and other producers and/or distributors of syndicated series, movies, specials, and non-team sports broadcast by television stations who have agreed to representation by MPAA (“MPAA-represented Program Suppliers”),1 in accordance with the procedural schedule set forth in Appendix A to the December 22, 2017 Order Consolidating Proceedings And Reinstating Case Schedule issued by the Copyright Royalty Judges (“Judges”), hereby submit their Written Direct Statement Regarding Distribution Methodologies (“WDS-D”) for the 2010-2013 cable royalty years2 in the consolidated 1 Lists of MPAA-represented Program Suppliers for each of the cable royalty years at issue in this consolidated proceeding are included as Appendix A to the Written Direct Testimony of Jane Saunders. -

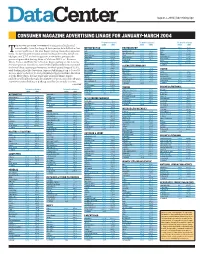

Ad Linage for Jan.-March 2004

Linage 1Q 07-26-04.qxd 7/29/04 3:03 PM Page 1 DataCenter August 2, 2004 | Advertising Age CONSUMER MAGAZINE ADVERTISING LINAGE FOR JANUARY-MARCH 2004 1st-quarter ad pages 1st-quarter ad pages 1st-quarter ad pages he second quarter's numbers for magazines brightened 2004 2003 2004 2003 2004 2003 considerably from the sluggish first quarter detailed below, but METROPOLITAN PHOTOGRAPHY Teen Vogue C. 132.66 80.49 Victoria C. 0.00 70.43 some trendlines of the year began making themselves apparent Boston 269.20 279.50 American Photo (6X) C. 109.02 96.65 T Vogue C. 639.48 715.27 Chicago 263.26 233.15 Outdoor Photographer (10X) 160.59 160.59 early. A near-flat performance at national business titles, which saw W Magazine C. 485.44 438.15 Chicago’s North Shore 126.63 122.37 PC Photo 104.87 120.57 Weight Watchers (6X) C. 148.13 126.18 ad pages sink 2.7% in the first quarter, nonetheless presages the Columbus Monthly 190.65 208.08 Popular Photography C. 380.00 390.76 Woman’s Day (15X) C. 347.02 357.89 Connecticut 136.26 176.50 TOTAL GROUP 754.48 768.57 positive figures that the big-three of McGraw-Hill Cos.' Business YM (11X) C. 108.69 190.16 Diablo 259.11 241.56 % CHANGE -1.83 Week, Forbes, and Time Inc.'s Fortune began putting on the board as TOTAL GROUP 11883.59 12059.13 Indianapolis Monthly 397.00 345.00 % CHANGE -1.46 the year went on. -

(OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (Inside) Interior Design

Publication Magazine Genre Frequency Language $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (inside) interior design review Art & Photo English Bimonthly . -

This Is a Test

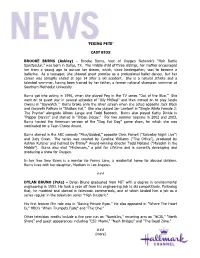

‘FIXING PETE’ CAST BIOS BROOKE BURNS (Ashley) – Brooke Burns, host of Oxygen Network‘s ―Hair Battle Spectacular,‖ was born in Dallas, TX. The middle child of three siblings, her mother encouraged her from a young age to pursue her dream, which, since kindergarten, was to become a ballerina. As a teenager, she showed great promise as a professional ballet dancer, but her career was abruptly ended at age 14 after a ski accident. She is a natural athlete and a talented swimmer, having been trained by her father, a former national champion swimmer at Southern Methodist University. Burns got into acting in 1996, when she played Peg in the TV series ―Out of the Blue.‖ She went on to guest star in several episodes of ―Ally McBeal‖ and then moved on to play Jessie Owens in ―Baywatch.‖ Burns broke onto the silver screen when she acted opposite Jack Black and Gwyneth Paltrow in ―Shallow Hal.‖ She also played Jan Lambert in ―Single White Female 2: The Psycho‖ alongside Allison Lange and Todd Babcock. Burns also played Kathy Dinkle in ―Pepper Dennis‖ and starred in ―Urban Decay.‖ For two summer seasons in 2002 and 2003, Burns hosted the American version of the ―Dog Eat Dog‖ game show, for which she was nominated for a Teen Choice Award. Burns starred in the ABC comedy ―Miss/Guided,‖ opposite Chris Parnell (―Saturday Night Live‖) and Judy Greer. The series was created by Caroline Williams (―The Office‖), produced by Ashton Kutcher and helmed by Emmy® Award-winning director Todd Holland (―Malcolm in the Middle‖). Burns also shot ―Mistresses,‖ a pilot for Lifetime and is currently developing and producing a show for Oxygen. -

Exemplar-Designer-Vs.-High-Street.Pdf

Exemplar Extended Project Unit: P301 Topic: Designer Vs. High Street Edexcel OSCA Assessment Exercise Portfolio 2011/12 Edexcel OSCA Assessment Exercise Portfolio 2011/12 Proposed project title: Designer VS high street Section One: Title, objective, responsibilities Title or working title of project (in the form of a question, commission or design brief) How do designers influence and affect the retail industry? Project objectives (eg, what is the question you want to answer? What do you want to learn how to do? What do you want to find out?): When carrying out my project one of the main questions I will be looking into is, what the difference between high street brands and designer brands is. I will be looking into the background information of Vera Wang, Versace, Topshop, River Island and two different fashion magazines. One of the questions I will be looking to answer is, how designers influence high street brands using the catwalk. I will also be looking to find out how designers cope with the pressure of having to keep on top of high street brands, and how they cope with the imitations that they find in most high street stores. I will be finding out key facts about two designer brands and two high street stores. I also want to find out how magazines use celebrity endorsement to advertise fashion products, and high street stores. If it is a group project, what will your responsibilities be? I will be taking on all responsibility of my project. I will be conducting all research, primary and secondary, and I will be writing up my own findings. -

Department of Journalism

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF JOURNALISM THE FRAMING OF FEMININITY IN POPULAR WOMEN'S MAGAZINES IN 2009: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF SEVENTEEN, GLAMOUR AND COSMOPOLITAN MAGAZINES JENNIFER HALEY HOFFMAN Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Journalism with honors in Journalism Reviewed and approved* by the following: Marie Hardin Associate Professor of Journalism Thesis Supervisor Bob Richards John & Ann Curley Professor of First Amendment Studies Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT At all levels of media, commercialism preys daily on women’s insecurities (Oppliger, 2008). Research demonstrates that women’s magazines may make assumptions that women’s priorities are to stay fit, vanish wrinkles and to mold their looks and behavior to please men. Oftentimes, women are encouraged to perceive themselves, and in turn their self-worth, through a male lens. Research shows that young girls and women look to magazines to help them make lifestyle choices. Research for this thesis involved a content analysis of the popular women’s magazines, Seventeen, Glamour and Cosmopolitan. More than 1,500 images of women and 500 stories were analyzed for their emphasis on beauty, sexuality, health, relationships and their depiction of race. The data collected and analyzed revealed that overall, the magazines focused most on sex/love, followed by beauty and fashion. Most articles did not emphasize relationships, but the majority of those that did focused on romantic relationships, with a minority focusing on friendships and workplace relationships. The majority of women were pictured in inactive, but non-sexual poses, and the depiction of race was on par with the U.S. -

Jonathan Hanousek Hair

JONATHAN HANOUSEK HAIR CELEBRITIES Ahna O'Reilly Brooke Smith Elizabeth Mitchell Alanis Morrissette Bryce Dallas Howard Elisabeth Moss Alexa Vega Candice Accola Elle MacPherson Alison Pill Candice Bergen Ellie Kemper Alyson Hannigan Carey Mulligan Emily Watson Amanda Bynes Carla Gugino Emma Willis America Ferrera Cat Deeley Emmy Rossum Amy Ryan Chris D’Elia Eva Mendes Amy Smart Chris Klein Eve Mauro Analeigh Tipton Christian Serratos Ever Carradine Angie Everhart Christina Applegate Fran Drescher AnnaLynne McCord Christina Hendricks Freida Pinto Anne Hathaway Christopher Freddy Rodriguez Anne Heche McDonald Gabriella Wilde Anthony LePaglia Constance Marie Gal Gadot Ashley Jensen Cybill Shepherd Giada De Laurentiis Audrina Patridge Cyndi Lauper Gillian Anderson Azita Ghanizada Daphne Rubin-Vega Gina Carano Barbara Hershey David Schwimmer Gina Bellman Bianca Kajlich Demi Moore Ginnifer Goodwin Bonnie Hunt Denise Richards Greta Gerwig Brittany Snow Diora Baird Gretchen Mol Brooke Shields Dylan Walsh Haley Bennett 1 Haylie Duff Kathy Najimy Melissa Etheridge Heather Graham Katie Finneran Meg Ryan Helen Hunt Kay Panabaker Megan Park Helen Mirren Keke Palmer Melissa Leo Hilary Duff Kelly Preston Mena Suvari Hilary Swank Kelly Hu Mia Maestro Jaime King Keri Russell Michael J. Fox Jaime Pressly Kim Raver Michaela Watkins Jaimie Alexander Kirstie Alley Michelle Dockery Jamie Lynn Sigler Kristin Bauer Michelle Forbes Jane Krakowski Kristin Carey Miguel Arteta Jeanne Tripplehorn Kristin Cavallari Minnie Driver Jenna Fischer Kristin Chenoweth Mira -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Vance Trimble Collection Trimble, Vance H. (1913– ). Papers, 1899–1997. 10.5 feet. Journalist and author. Correspondence (1937–1995); research files (1986–1990); manuscripts (1953–1990); newspaper clippings, magazines, and scrapbooks (1899–1997) from the life and career of journalist and 1960 Pulitzer Prize winner Vance H. Trimble. In 1960, Trimble was awarded a journalism “triple crown”: the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting, the Sigma Delta Chi award for distinguished Washington correspondence, and the Raymond Clapper Award for the year’s best Washington reporting, for an investigation of nepotism and payroll abuses in Congress. The collection also includes publicity and book reviews for Trimble’s biographies of Happy Chandler, E. W. Scripps, and Sam Walton. _____________________________________________________________________ Biographical Note: Newspaper editor and author Vance Henry Trimble was born to Guy L. and Josephine (Crump) Trimble, July 6, 1913 in Harrison, Arkansas. He attended public schools in Wewoka, Oklahoma, during childhood. Married Elzene Miller January 9, 1932, and had one daughter, Carol Ann (Nordheimer). Trimble won the “triple crown” in 1960 by receiving a Pulitzer prize in journalism, the Raymond Clapper award, and the Sigma Delta Chi award for distinguished Washington correspondence for a series of investigational articles on Congressional nepotism. Trimble began his news career as a cub reporter for the Okemah Daily Leader in 1927, and had a successful career in news reporting and editing in Oklahoma, Texas, Washington D.C., and Kentucky. Most notable among the positions Trimble held are reporter and managing editor for the Houston Press, news editor of the Scripps-Howard Newspaper Alliance, and editor of the Kentucky Post and Times-Star. -

Sample Publisher List

SAMPLE PUBLISHER LIST ARTS & BUSINESS & FINANCE HEALTH & FITNESS HOBBIES & INTERESTS NEWS & INFORMATION SOCIAL ENTERTAINMENT Barron’s All Recipes Aces Traffic Pack Classic Answers.com Adsmoville Elle/ Elle Girl Bloomberg/ Bloomberg Radio Austin Physicians AutoWallpaperChanger Arizona Republic AIM Buzzmedia Entertainment Tonight Business Insider Calciomercato Bigoven AZ Central News Business Insider Cyber Presse Eonline Business Week Cardio3.com Bubble Breaker Free Business Week Echofon Fchat CheckBook CHOW Bubble Burst Free CBS News/ Local News eVite IMBD CNBC Real-Time Denise Austin Celeb Hub CNET Friend Caster Menu Clock Free CNN Money EatingWell.com Chip Chick Daily Herald Heywire Moviefone Daily Finance Everyday Health Cozi Demand Media Jumbuck OK! Dow Jones Fit Pregnancy Daily Glow Detroit Free Press Mocospace Radar Online Forbes Ifood Media Dots Detroit News Opera Mini Rolling Stone Gannett Iron Man Magazine FreeCell Dictionary.com Pinger Star Magazine Journal of Commerce Jillian Michaels Ghost Radar Classic DSTV Online Plume The Onion MarketWatch Joy Bauer Hearts Epicurious Pocket Express MSNBC/ MSNBC TV Map My Fitness iGossip Evening Standard Forbes Quick Meme MUSIC Nasdaq.com Men’s Fitness Ka-Glom Fox News/ Local News Text Me Billboard Pocket Money Men’s Journal Lagunex Domino CBS Music Freedom Media Texts From Last Night Smart Money Period Calculator Life & Style Magazine La Vibra Handmark Tweetcaster The Guardian Physicians News Now Limelife MusicHub Hearst News Ubersocial The Street SBD Lucky Huffington Post Pandora Ubertwitter