Irrigation Basics for Eastern Washington Vineyards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

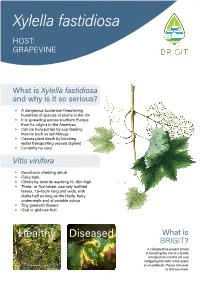

Xylella Fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE

Xylella fastidiosa HOST: GRAPEVINE What is Xylella fastidiosa and why is it so serious? ◆ A dangerous bacterium threatening hundreds of species of plants in the UK ◆ It is spreading across southern Europe from its origins in the Americas ◆ Can be transported by sap-feeding insects such as spittlebugs ◆ Causes plant death by blocking water transporting vessels (xylem) ◆ Currently no cure Vitis vinifera ◆ Deciduous climbing shrub ◆ Flaky bark ◆ Climbs by tendrils reaching 15–18m high ◆ Three- or five-lobed, coarsely toothed leaves, 7.5–15cm long and wide, with stalks half as long as the blade, hairy underneath and of variable colour ◆ Tiny greenish flowers ◆ Oval or globose fruit Healthy Diseased What is BRIGIT? A collaborative project aimed at reducing the risk of a Xylella introduction into the UK and mitigating the risks in the event of an outbreak. Please turn over to find out more. What to look 1 out for 2 ◆ Marginal leaf scorch 1 ◆ Leaf chlorosis 2 ◆ Premature loss of leaves 3 ◆ Matchstick petioles 3 ◆ Irregular cane maturation (green islands in stems) 4 ◆ Fruit drying and wilting 5 ◆ Stunting of new shoots 5 ◆ Death of plant in 1–5 years Where is the plant from? 3 ◆ Plants sourced from infected countries are at a much higher risk of carrying the disease-causing bacterium Do not panic! 4 How long There are other reasons for disease symptoms to appear. Consider California. of University Montpellier; watercolour, RHS Lindley Collections; “healthy”, RHS / Tim Sandall; “diseased”, J. Clark, California 3 J. Clark & A.H. Purcell, University of California 4 J. Clark, University of California 5 ENSA, Images © 1 M. -

Basic Soil Science W

Basic Soil Science W. Lee Daniels See http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/430/430-350/430-350_pdf.pdf for more information on basic soils! [email protected]; 540-231-7175 http://www.cses.vt.edu/revegetation/ Well weathered A Horizon -- Topsoil (red, clayey) soil from the Piedmont of Virginia. This soil has formed from B Horizon - Subsoil long term weathering of granite into soil like materials. C Horizon (deeper) Native Forest Soil Leaf litter and roots (> 5 T/Ac/year are “bio- processed” to form humus, which is the dark black material seen in this topsoil layer. In the process, nutrients and energy are released to plant uptake and the higher food chain. These are the “natural soil cycles” that we attempt to manage today. Soil Profiles Soil profiles are two-dimensional slices or exposures of soils like we can view from a road cut or a soil pit. Soil profiles reveal soil horizons, which are fundamental genetic layers, weathered into underlying parent materials, in response to leaching and organic matter decomposition. Fig. 1.12 -- Soils develop horizons due to the combined process of (1) organic matter deposition and decomposition and (2) illuviation of clays, oxides and other mobile compounds downward with the wetting front. In moist environments (e.g. Virginia) free salts (Cl and SO4 ) are leached completely out of the profile, but they accumulate in desert soils. Master Horizons O A • O horizon E • A horizon • E horizon B • B horizon • C horizon C • R horizon R Master Horizons • O horizon o predominantly organic matter (litter and humus) • A horizon o organic carbon accumulation, some removal of clay • E horizon o zone of maximum removal (loss of OC, Fe, Mn, Al, clay…) • B horizon o forms below O, A, and E horizons o zone of maximum accumulation (clay, Fe, Al, CaC03, salts…) o most developed part of subsoil (structure, texture, color) o < 50% rock structure or thin bedding from water deposition Master Horizons • C horizon o little or no pedogenic alteration o unconsolidated parent material or soft bedrock o < 50% soil structure • R horizon o hard, continuous bedrock A vs. -

So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee

Agricultural Extension Service The University of Tennessee PB 1689 So You Want to Grow Grapes in Tennessee 1 conditions. American grapes are So You Want to Grow versatile. They may be used for fresh consumption (table grapes) or processed into wine, juice, jellies or Grapes in Tennessee some baked products. Seedless David W. Lockwood, Professor grapes are used mostly for fresh Plant Sciences and Landscape Systems consumption, with very little demand for them in wines. Yields of seedless varieties do not match ennessee has a long history of grape production. Most recently, those of seeded varieties. They are T passage of the Farm Winery Act in 1978 stimuated an upsurge of also more susceptible to certain interest in grape production. If you are considering growing grapes, the diseases than the seeded American following information may be useful to you. varieties. French-American hybrids are crosses between American bunch 1. Have you ever grown winery, the time you spend visiting and V. vinifera grapes. Their grapes before? others will be a good investment. primary use is for wine. uccessful grape production Vitis vinifera varieties are used S requires a substantial commit- 3. What to grow for wine. Winter injury and disease ment of time and money. It is a American problems seriously curtail their marriage of science and art, with a - seeded growth in Tennessee. good bit of labor thrown in. While - seedless Muscadines are used for fresh our knowledge of how to grow a French-American hybrid consumption, wine, juice and jelly. crop of grapes continues to expand, Vitis vinifera Vines and fruits are not very we always need to remember that muscadine susceptible to most insects and some crucial factors over which we Of the five main types of grapes diseases. -

Late Harvest

TASTING NOTES LATE HARVEST DESCRIPTION 2017 The Tokaj legend has grown and grown in its four-hundred years of history; but it was not until 1630, when the greatness of Oremus vineyard was first spoken of. Today, it is the one with greatest universal acclaim. The Tokaj region lies within the range of mountains in Northeast Hungary. Oremus winery is located at the geographical heart of this region. At harvest, bunches are picked several times a day but. Only those containing at least 50% of botrytis grapes, are later pressed, giving the noble rot a leading role. Late Harvest is an interesting coupage of different grape varieties producing an exceptionally well-balanced wine. Fermentation takes place in new Hungarian oak barrels (136- litre “Gönc” and 220-litre “Szerednye”) for 30 days and stops naturally when alcohol level reaches 12 %. Then, the wine ages in Hungarian oak for six months and sits in bottle for a 15-month ageing period. Late Harvest is a harmonious, fresh, silky wine. It is very versatile, providing a new experience in each sip. GENERAL INFORMATION Alcohol by volume - 11 % Sugar - 119 g/l Acidity - 9 g/l Variety - Furmint, Hárslevelü, Zéta and Sárgamuskotály Average age of vineyard - 20 years Vineyard surface area - 91 ha Planting density - 5,660 plants/ha Altitude - 200 m Yield - 1,300 kg/ha Harvest - 100% Hand-picked in 2-3 rounds from late September to early November 2017 VINEYARD CYCLE After the coldest January of the past decade, spring and summer brought average temperatures and precipitation in good dispersion. Mid-September rain allows the development of noble rot to spread in the vineyard, turning 2017 into one of the greatest vintages for sweet wine in the last decade. -

Chamisal Vineyards Intern Training Manual

i Chamisal Vineyards Intern Training Manual A Senior Project presented to the Faculty of the Agricultural Science California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Agricultural Science by Nicole Adam October, 2013 © 2013 Nicole Adam ii Acknowledgements Chamisal Vineyard’s assistant winemaker played a large role in the composition of the Chamisal Vineyards Harvest Intern Training Manual. Throughout my employment at Chamisal Vineyards I have learned an enormous amount about the wine industry and winemaking in general. Working with Michael Bruzus on this manual was a great experience. He is a fantastic teacher and very patient supervisor. Although Mr. Bruzus recently resigned from his position at Chamisal, he will always be a part of the Chamisal Vineyards wine cellar family. iii Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………. ii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………… iii Chapter One: Introduction to Project…………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………. 1 Statement of the Problem……………………………………………………… 1 Importance of the Project…………………………………………………........ 2 Purpose of the Project…………………………………………………………. 2 Objectives of the Project……………………………………………………..... 3 Summary………………………………………………………………………. 3 Chapter Two: Review of Literature……………………………………………...... 4 Writing an Employee Training Manual……………………………………….. 4 Parts of an Employee Training Manual………………………………………... 5 OSHA Regulations…………………………………………………………….. 6 Cleaning Chemicals Commonly -

Decision Support Systems for Water Management

Decision Support Systems for Water Management Mladen Todorović CIHEAM – IAM BARI [email protected] LARI, Tal Amara, Lebanon, 6-10 December 2016 DSSConcept for water of LARI management, EWS Improvement Mladen, Vieri Todorovic Tarchiani INTRODUCTION TO THE COURSE Course objectives • Overall objective: – to provide basic (and advanced) knowledge about the application of decision support systems for water management in Mediterranean environments. • Specific objective: – To explain the structure, approach and purpose of decision support systems (DSS) in general and for water management and agricultural applications in particular; – To give a grounding about Geographical Information System (GIS), its structure, database development, format and management, and GIS/DSS applications and links in agriculture and water management – To expose about the use of new technologies (e.g. remote sensing – satellite and ground-based platforms) and modelling tools and their integration with DSS/GIS applications in agriculture and water management – To present and discuss the examples of DSS/GIS/modern technologies integration and applications in agriculture and water management and especially for risk assessment and alert/emergency management; – To start-up a dialogue and process of development of a DSS for early warning drought risk and irrigation management in Lebanon. The contents of the course 1 • DSS definition, approach, scales of application, components (data and database management, models, software tools, query tool, etc.), optimization criteria, single/multi objective criteria definition, model attributes, objective functions, constraints, quantitative and qualitative risk assessment. • GIS definition, components, benefits, limitations, sources of information, data models (vector, raster), applications in agriculture and precision farming, GPS/GIS integration, database development, operational functionalities, spatial queries, data classification, hydrological balance in GIS, GIS/DSS integration, decision making process, examples of application. -

Deficit Irrigation Management of Maize in the High Plains Aquifer Region: a Review Daran Rudnick University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Biological Systems Engineering: Papers and Biological Systems Engineering Publications 2-2019 Deficit Irrigation Management of Maize in the High Plains Aquifer Region: A Review Daran Rudnick University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Sibel Irmak University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] C. West Texas Tech University J.L. Chavez Colorado State University I. Kisekka University of California, Davis See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosysengfacpub Part of the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons, Environmental Engineering Commons, and the Other Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons Rudnick, Daran; Irmak, Sibel; West, C.; Chavez, J.L.; Kisekka, I.; Marek, T.H.; Schneekloth, J.P.; Mitchell McCallister, D.; Sharma, V.; Djaman, K.; Aguilar, J.; Schipanski, M.E.; Rogers, D.H.; and Schlegel, A., "Deficit Irrigation Management of Maize in the High Plains Aquifer Region: A Review" (2019). Biological Systems Engineering: Papers and Publications. 629. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosysengfacpub/629 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Systems Engineering at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Systems Engineering: Papers and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Daran Rudnick, Sibel Irmak, C. West, J.L. Chavez, I. Kisekka, T.H. Marek, J.P. Schneekloth, D. Mitchell McCallister, V. Sharma, K. Djaman, J. Aguilar, M.E. Schipanski, D.H. Rogers, and A. Schlegel This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosysengfacpub/ 629 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION Vol. -

Canopy Microclimate Modification for the Cultivar Shiraz II. Effects on Must and Wine Composition

Vitis 24, 119-128 (1985) Roseworthy Agricultural College, Roseworth y, South Australia South Australian Department of Agriculture, Adelaide, South Austraha Canopy microclimate modification for the cultivar Shiraz II. Effects on must and wine composition by R. E. SMART!), J. B. ROBINSON, G. R. DUE and c. J. BRIEN Veränderungen des Mikroklimas der Laubwand bei der Rebsorte Shiraz II. Beeinflussung der Most- und Weinzusammensetzung Z u sam menfa ss u n g : Bei der Rebsorte Shiraz wurde das Ausmaß der Beschattung innerha lb der Laubwand künstlich durch vier Behandlungsformen sowie natürlicherweise durch e ine n Wachstumsgradienten variiert. Beschattung bewirkte in den Traubenmosten eine Erniedri gung de r Zuckergehalte und eine Erhöhung der Malat- und K-Konzentrationen sowie der pH-Werte. Die Weine dieser Moste wiesen ebenfalls höhere pH- und K-Werte sowie einen venin gerten Anteil ionisierter Anthocyane auf. Statistische Berechnungen ergaben positive Korrelatio nen zwischen hohen pH- und K-Werten in Most und Wein einerseits u11d der Beschattung der Laubwand andererseits; die Farbintensität sowie die Konzentrationen der gesamten und ionisier ten Anthocyane und der Phenole waren mit der Beschattung negativ korreliert. Zur Beschreibung der Lichtverhältnisse in der Laubwand wurde ei11 Bonitierungsschema, das sich auf acht Merkmale stützt, verwendet; die hiermit gewonne nen Ergebnisse korrelierten mit Zucker, pH- und K-Werten des Mostes sowie mit pH, Säure, K, Farbintensität, gesamten und ionj sierten Anthocyanen und Phenolen des Weines. Starkwüchsige Reben lieferten ähnliche Werte der Most- und Weinzusammensetzung wie solche mit künstlicher Beschattung. K e y wo r d s : climate, light, growth, must quality, wine quality, malic acid, potassium, aci dity, anthocyanjn. -

A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible Through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application

agronomy Article A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application Ján Horák 1,* , Tatijana Kotuš 1, Lucia Toková 1, Elena Aydın 1 , Dušan Igaz 1 and Vladimír Šimanský 2 1 Department of Biometeorology and Hydrology, Faculty of Horticulture and Landscape Engineering, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] (T.K.); [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (D.I.) 2 Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agrobiology and Food Resources, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Recent findings of changing climate, water scarcity, soil degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions have brought major challenges to sustainable agriculture worldwide. Biochar application to soil proves to be a suitable solution to these problems. Although the literature presents the pros and cons of biochar application, very little information is available on the impact of repeated application. In this study, we evaluate and discuss the effects of initial and reapplied biochar (both in rates of 0, 10, and 20 t ha−1) combined with N fertilization (at doses of 0, 40, and 80 kg ha−1) on soil properties and N O emission from Haplic Luvisol in the temperate climate zone (Slovakia). Results showed that 2 biochar generally improved the soil properties such as soil pH(KCl) (p ≤ 0.05; from acidic towards Citation: Horák, J.; Kotuš, T.; Toková, moderately acidic), soil organic carbon (p ≤ 0.05; an increase from 4% to over 100%), soil water L.; Aydın, E.; Igaz, D.; Šimanský, V. -

Is Precision Viticulture Beneficial for the High-Yielding Lambrusco (Vitis

AJEV Papers in Press. Published online April 1, 2021. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture (AJEV). doi: 10.5344/ajev.2021.20060 AJEV Papers in Press are peer-reviewed, accepted articles that have not yet been published in a print issue of the journal or edited or formatted, but may be cited by DOI. The final version may contain substantive or nonsubstantive changes. 1 Research Article 2 Is Precision Viticulture Beneficial for the High-Yielding 3 Lambrusco (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapevine District? 4 Cecilia Squeri,1 Irene Diti,1 Irene Pauline Rodschinka,1 Stefano Poni,1* Paolo Dosso,2 5 Carla Scotti,3 and Matteo Gatti1 6 1Department of Sustainable Crop Production (DI.PRO.VE.S.), Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Via 7 Emilia Parmense 84 – 29122 Piacenza, Italy; 2Studio di Ingegneria Terradat, via A. Costa 17, 20037 8 Paderno Dugnano, Milano, Italy; and 3I.Ter Soc. Cooperativa, Via E. Zacconi 12. 40127, Bologna, Italy. 9 *Corresponding author ([email protected]; fax: +39523599268) 10 Acknowledgments: This work received a grant from the project FIELD-TECH - Approccio digitale e di 11 precisione per una gestione innovativa della filiera dei Lambruschi " Domanda di sostegno 5022898 - 12 PSR Emilia Romagna 2014-2020 Misura 16.02.01 Focus Area 5E. The authors also wish to thank all 13 growers who lent their vineyards, and G. Nigro (CRPV) and M. Simoni (ASTRA) for performing micro- 14 vinification analyses. 15 Manuscript submitted Sept 26, 2020, revised Dec 8, 2020, accepted Feb 16, 2021 16 This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY license 17 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). -

Late Harvest Wine: Cul�Var Selec�On & Wine Tas�Ng Late Harvest - Vi�Culture

Late Harvest Wine: Culvar Selecon & Wine Tasng Late Harvest - Viculture • Le on vine longer than usual • Longer ripening period allows development of sugar and aroma • Berries are naturally dehydrated on the vine • Dehydraon increases relave concentraon of aroma, °Brix, and T.A. Late harvest wine – lower Midwest Les Bourgeois Vineyards 24 Nov 2008 - Rocheport, Missouri hp://lubbockonline.com/stories/121408/bus_367326511.shtm Desired characteriscs - of a late harvest culvar in Kentucky • Ripens mid to late season • Thick skin?? • Not prone to shaer • pH slowly rises • Moderate to high T.A. • High °Brix • Desirable aroma Late Harvest Culvars – for Kentucky Currently successful: • Vidal blanc • Chardonel ------------------------ Potenally successful: • Vignoles • Viognier • Rkatseteli • Pe1te manseng Late Harvest Vidal blanc Benefits • High T.A. • Thick cucle • Later ripening Suscepble to: • sour rot • Powdery & Downey Vidal blanc • Early season disease control especially important Vidal blanc Late Harvest Vidal blanc – Sour rot • Bunch rot complex • May require selecve harvest Late Harvest Vignoles • High acidity • High potenal °Brix • Aroma intensity increases with hang me ----------------------------- • Prone to bunch rot • Low yields Late Harvest Vignoles Late Harvest Vignoles Quesonable Late Harvest Culvars – for Kentucky Currently unsuccessful: • Chardonnay • Riesling • Cayuga white • Villard blanc • Traminee Tricky Traminee Tricky Traminee • Ripens early • Thin skin • Berry shaer • pH quickly rises • Low T.A. • Low °Brix #1- Late Harvest Vidal blanc Blumenhof Winery – Vintage 2009 32 °Brix @ harvest 12.5% residual sugar 10.1% alcohol #2- Late Harvest Vignoles Stone Hill Winery – Vintage 2010 34 °Brix @ harvest 15% residual sugar 11.4% alcohol #3- Late Harvest Vignoles University of Kentucky – Vintage 2010 28 °Brix @ harvest 10% residual sugar 10.4% alcohol #4- Late Harvest Seyval blanc St. -

Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis Vinifera During Lasiodiplodia Theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Dual RNA Sequencing of Vitis vinifera during Lasiodiplodia theobromae Infection Unveils Host–Pathogen Interactions Micael F. M. Gonçalves 1 , Rui B. Nunes 1, Laurentijn Tilleman 2 , Yves Van de Peer 3,4,5 , Dieter Deforce 2, Filip Van Nieuwerburgh 2, Ana C. Esteves 6 and Artur Alves 1,* 1 Department of Biology, CESAM, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal; [email protected] (M.F.M.G.); [email protected] (R.B.N.) 2 Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Campus Heymans, Ottergemsesteenweg 460, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (F.V.N.) 3 Department of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] 4 Center for Plant Systems Biology, VIB, 9052 Ghent, Belgium 5 Department of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0028, South Africa 6 Faculty of Dental Medicine, Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Health (CIIS), Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Estrada da Circunvalação, 3504-505 Viseu, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-234-370-766 Received: 28 October 2019; Accepted: 29 November 2019; Published: 3 December 2019 Abstract: Lasiodiplodia theobromae is one of the most aggressive agents of the grapevine trunk disease Botryosphaeria dieback. Through a dual RNA-sequencing approach, this study aimed to give a broader perspective on the infection strategy deployed by L. theobromae, while understanding grapevine response. Approximately 0.05% and 90% of the reads were mapped to the genomes of L.