Magnetic Field Detection Limits for Ultraclean Graphene Hall Sensors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design and Construction of a Tachometer

Design and Construction of a Tachometer Author: David Tisaj November 2014 Supervisors: Dr Sujeewa Hettiwatte & Dr Gareth Lee Project Outline In this project the student will design and construct a contact-less tachometer which could be used in the power engineering lab. The output should be a 6-digit display of revs/min and radians per second. The device should enable the use of several sensors (such as optical or Hall Effect). The device should be tested to demonstrate the ability to display at least 5 significant figures after a reasonable gating period. 2 I Acknowledgements I’d like to say thank you to Dr Gareth Lee for being my supervisor and coach throughout this thesis and Dr Sujeewa Hettiwatte for providing project specifications. I’d like to thank Mr Iafeta Laava for helping me build my circuit and attaching wires with headers very neatly which made my circuit look professional. I’d also like to thank my family and friends for pushing me through involving: my parents, Dusan Sibanic, Warwick Smith, Holly Poole, and Lyrian Evans. I’d like to thank “that computer shop” for recovering part of my thesis after I incurred a corrupt hard drive. Note to self and others: back up your work! And finally I’d like to thank all the websites online who have relinquished their copyright so it can be used in this thesis to explain topics in more clarity. 3 II Abstract The purpose of this report is to provide a guided tour of how everything was achieved by choosing the right parts, implementation and building, testing, results and of course to inspire future projects and students into making student level tachometers because they all come in different shapes and sizes. -

Dynamic Differential Hall Effect Sensor TLE4926C-HT E6547

Dynamic Differential Hall Effect Sensor TLE4926C-HT E6547 Data Sheet Version 1.1 Features • High sensitivity • Single chip solution • Symmetrical thresholds PG-SSO-3-92 • High resistance to Piezo effects • South and north pole pre-induction possible • Low cut-off frequency • Digital output signal • Advanced performance by dynamic self calibration principle • Two-wire and three-wire configuration possible • Wide operating temperature range • Fast start-up time • Large operating air-gaps • Reverse voltage protection at Vs- PIN • Short- circuit and over temperature protection of output • Digital output signal (voltage interface) • Module style package with two integrated capacitors: • 4.7nF between Q and GND 1 • 47nF between VS and GND: Needed for micro cuts in power supply Type Marking Ordering Code Package TLE4926C-HT E6547 26D8 SP000718258 PG-SSO-3-92 1 value of capacitor: 47nF±10%; (excluded drift due to temperature and over lifetime); ceramic: X8R; maximum voltage: 50V. Data Sheet Page 1 of 25 General Information The TLE4926C-HT E6547 is an active Hall sensor suited to detect the motion and position of ferromagnetic and permanent magnet structures. An additional self-calibration module has been implemented to achieve optimum accuracy during normal running operation. It comes in a three-pin package for the supply voltage and an open drain output. VS GND Q 47nF 4.7nF Figure 1: Pin configuration PG-SSO-3-92 Pin definition and Function Pin No. Symbol Function 1 VS Supply Voltage 2 GND Ground 3 Q Open Drain Output Functional Description The differential Hall sensor IC detects the motion and position of ferromagnetic and permanent magnet structures by measuring the differential flux density of the magnetic field. -

Use of Hall Effect Sensors for Protection and Monitoring Applications March 2018 Use of Hall Effect Sensors for Protection and Monitoring Applications

PSRC I24 Use of Hall Effect Sensors for Protection and Monitoring Applications March 2018 Use of Hall Effect Sensors for Protection and Monitoring Applications A report to the Relaying Practices Subcommittee I Power System Relaying and Control Committee IEEE Power & Energy Society Prepared by Working Group I-24 Working Group Assignment Report on the use of Hall Effect Sensors for Protection and Monitoring Applications. The report will discuss the technology, and compare with other sensing technologies. Working Group Members Jim Niemira – Chair Jeff Long – Vice Chair Jeff Burnworth John Buffington Amir Makki Mario Ranieri George Semati Alex Stanojevic Mark Taylor Phil Zinck Page 1 of 32 PSRC I24 Use of Hall Effect Sensors for Protection and Monitoring Applications March 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Working Group Assignment .......................................................................................................................... 1 Working Group Members ............................................................................................................................. 1 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Theory – What is Hall Effect .................................................................................................................. 5 3 Current Sensing Hall Effect Sensors ...................................................................................................... 6 4 Sensor Types -

Hall Sensor Output Signal Fault-Detection &Amp

MATEC Web of Conferences59, 01007 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/2016 59 01007 ICFST 2016 Hall Sensor Output Signal Fault-Detection & Safety Implementation Logic SangHun, Lee1, HongSeuk, Oh2 1 Intelligent automotive team, Daegu Mechatronics & Materials Institute, S.Korea 22STARGROUPIND. LTD, S.Korea Abstract. Recently BLDC motors have been popular in various industrial applications and electric mobility. Recently BLDC motors have been popular in various industrial applications and electric mobility. In most brushless direct current (BLDC) motor drives, there are three hall sensors as a position reference. Low resolution hall effect sensor is popularly used to estimate the rotor position because of its good comprehensive performance such as low cost, high reliability and sufficient precision. Various possible faults may happen in a hall effect sensor. This paper presents a fault-tolerant operation method that allows the control of a BLDC motor with one faulty hall sensor and presents the hall sensor output fault-tolerant control strategy. The situations considered are when the output from a hall sensor stays continuously at low or high levels, or a short-time pulse appears on a hall sensor signal. For fault detection, identification of a faulty signal and generating a substitute signal, this method only needs the information from the hall sensors. There are a few research work on hall effect sensor failure of BLDC motor. The conventional fault diagnosis methods are signal analysis, model based analysis and knowledge based analysis. The proposed method is signal based analysis using a compensation signal for reconfiguration and therefore fault diagnosis can be fast. The proposed method is validated to execute the simulation using PSIM. -

Graphene Sensors Find Subtleties in Magnetic Fields 20 August 2020

Graphene sensors find subtleties in magnetic fields 20 August 2020 Nowack's lab specializes in using scanning probes to conduct magnetic imaging. One of their go-to probes is the superconducting quantum interference device, or SQUID, which works well at low temperatures and in small magnetic fields. "We wanted to expand the range of parameters that we can explore by using this other type of sensor, which is the Hall-effect sensor," said doctoral student Brian Schaefer, the paper's lead author. "It can work at any temperature, and we've shown it can work up to high magnetic fields as well. Hall sensors have been used at high magnetic fields before, but they're usually not able to detect small Credit: CC0 Public Domain magnetic field changes on top of that magnetic field." The Hall effect is a well-known phenomenon in As with actors and opera singers, when measuring condensed matter physics. When a current flows magnetic fields it helps to have range. through a sample, it is bent by a magnetic field, creating a voltage across both sides of the sample Cornell researchers used an ultrathin graphene that is proportional to the magnetic field. "sandwich" to create a tiny magnetic field sensor that can operate over a greater temperature range Hall-effect sensors are used in a variety of than previous sensors, while also detecting technologies, from cellphones to robotics to anti- miniscule changes in magnetic fields that might lock brakes. The devices are generally built out of otherwise get lost within a larger magnetic conventional semiconductors like silicon and background. -

Study of Hall Effect Sensor and Variety of Temperature Related Sensitivity

308 J. Eng. Technol. Sci., Vol. 49, No. 3, 2017, 308-321 Study of Hall Effect Sensor and Variety of Temperature Related Sensitivity Awadia Ahmed Ali, Guo Yanling * & Chang Zifan College of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin150040, PR China *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Hall effect sensors are used in many applications because they are based on an ideal magnetic field sensing technology. The most important factor that determines their sensitivity is the material of which the sensor is made. Properties of the material such as carrier concentration, carrier mobility and energy band gap all vary with temperature. Thus, sensitivity is also influenced by temperature. In this study, current-related sensitivity and voltage-related sensitivity were calculated in the intrinsic region of temperature for two commonly used materials, i.e. Si and GaAs. The results showed that at the same temperature, GaAs can achieve higher sensitivity than Si and it has a larger band gap as well. Therefore, GaAs is more suitable to be used in applications that are exposed to different temperatures. Keywords: carrier concentration; gallium arsenide; Hall effect sensor; materials; sensitivity; silicon. 1 Introduction A Hall effect sensor is a semiconductor device that converts a magnetic field to electric voltage. Edwin Hall discovered the Hall effect phenomenon in 1879 [1,2]. However, its application was restricted to laboratory experiments until 1950. The huge developments in the production of semiconductors and electronics made it easy to integrate a Hall effect sensing element with a microsystem in a single integrated circuit. Nowadays, Hall sensors have a wide range of applications in many different devices, from computers to vehicles, airplanes and medical equipment. -

AN4058, BLDC Motor Control with Hall Effect Sensors Using The

Freescale Semiconductor Document Number: AN4058 Application Note Rev. 0, 4/2010 BLDC Motor Control with Hall Effect Sensors Using the 9S08MP by: Eduardo Viramontes Systems and Applications Engineering Freescale Technical Support 1 Introduction Contents 1 Introduction...........................................................1 This application note describes a brushless DC (BLDC) motor control system using a predefined hardware reference design. It 2 System Description...............................................1 explains the hardware concept (not in detail), for further details 2.1 BLDC Basics.................................................2 about the hardware, look for the user guide titled 3-Phase 2.1.1 Three-Phase BLDC Motor....................2 BLDC/PMSM Low-Voltage Motor Control Drive (document 2.1.2 Commutation—Moving the BLDC LVMCDBLDCPMSMUG) and the user manual titled Motor.....................................................3 MC9S08MP16 Controller Daughter Board for BLDC/PMSM Motor Control Drive (document LVBLDCMP16DBUM) at 2.1.3 Controlling Speed and Torque...............6 www.freescale.com. 2.2 9S08MP16 Controller Advantages and Features.........................................................9 This application uses the MC9S08MP 8-bit microcontroller. The 2.3 System Block Diagram.................................9 device has specialized control hardware that allows for reduced software overhead and higher control efficiency. 3 Software Description...........................................10 BLDC motors are more frequently -

Development of a Label-Free Graphene Hall Effect Biosensor

Development of a Label-free Graphene Hall Effect Biosensor By Davut Izci School of Engineering A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Science, Agriculture and Engineering for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my supervisors John Hedley, Neil Keegan, Harriet Grigg and Konstantin Vasilevskiy for their guidance and support throughout my project and group members of Institute of Cellular Medicine; Carl Dale, Julia Spoors and Chen Fu for their help. Particularly Carl for his help in guiding me to graphene fabrication, characterisation and planning appropriate biochemical procedures for detection of biomolecules and observation of the system response. I would also like to thank the Nexus team at Newcastle; Anders Barlow, Jose Portoles and Billy Murdoch for their help and guidance in performing XPS, HIM imaging and providing training for performing SEM and EDX. In addition, I would like to thank to group members of Microsystems, Michelle Pozzi for his support in providing me equipment and Richie Burnett for valuable discussions on design and fabrication of PCB based Hall sensors and signal processing board. Also, a big thanks to technicians in electronics workshop Paul Watson and Paul Harrison for helping me with tools and equipment I needed throughout this time. Isabel Arce-Garcia in Advanced Chemical and Materials Analysis Department also deserves credit. I am grateful for her help in Raman analysis of my samples and surface coating works. I am grateful to my colleagues Tom Bamford for his help in printing graphene oxide devices, and Sinziana Popescu for her help on photoelectrochemical etching process on silicon carbide. -

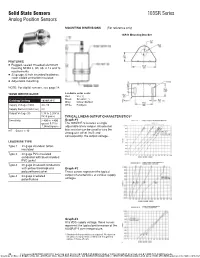

Solid State Sensors 103SR Series Analog Position Sensors

Solid State Sensors 103SR Series Analog Position Sensors MOUNTING DIMENSIONS (For reference only) 1SR15 Mounting Bracket FEATURES 1 Rugged, sealed threaded aluminum housing NEMA 3, 3R, 3S, 4, 12 and 13 requirements 1 22 gauge, 6 inch stranded leadwires, color coded and teflon insulated 1 Adjustable mounting NOTE: For digital sensors, see page 14. 103SR ORDER GUIDE Leadwire color code: Red Vs (+) Black Ground (–) Catalog Listing 103SR3F-5 Gray Linear Output Supply Voltage (VDC) 4 to 10 White R Adjust Supply Current (mA max.) 3.5 Output Voltage (V) 1.75 to 2.25V at 5V, 0 gauss TYPICAL LINEAR OUTPUT CHARACTERISTICS* Sensitivity (–400 to +400 Graph #1 The 103SR3F-5 features a single gauss) 0.75 to 1.06mV/gauss adjustable linear output. An external mT = Gauss ´ 10-1 bias resistor can be used to vary the zero gauss offset (null) and consequently, the output voltage. LEADWIRE TYPE Type 1 22 gage stranded, teflon insulated Type 2 22 gage PVC insulated conductor with black molded PVC jacket Type 3 22 gage insulated conductors with yellow thermoplastic Graph #2 polyurethane jacket These curves represent the typical Type 4 24 gage irradiated output characteristics at various supply voltages. polyethylene Graph #3 At 5 VDC supply voltage, these curves represent the typical performance of the 103SR3F-5 over temperature. * Illustrated characteristics are typical. Production lot sensor characteristics will be in the general range of those shown. PDFINFO p a g e - 0 2 4 24 Honeywell 1 MICRO SWITCH Sensing and Control 1 1-800-537-6945 USA 1F1-815-235-6847 -

A Comprehensive Review of Integrated Hall Effects in Macro

sensors Review A Comprehensive Review of Integrated Hall Effects in Macro-, Micro-, Nanoscales, and Quantum Devices Avi Karsenty 1,2 1 Advanced Laboratory of Electro-Optics (ALEO), Department of Applied Physics/Electro-Optics Engineering, Lev Academic Center, 9116001 Jerusalem, Israel; [email protected]; Tel.: +972-2-675-1140 2 Nanotechnology Center for Education and Research, Lev Academic Center, 9116001 Jerusalem, Israel Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 22 July 2020; Published: 27 July 2020 Abstract: A comprehensive review of the main existing devices, based on the classic and new related Hall Effects is hereby presented. The review is divided into sub-categories presenting existing macro-, micro-, nanoscales, and quantum-based components and circuitry applications. Since Hall Effect-based devices use current and magnetic field as an input and voltage as output. researchers and engineers looked for decades to take advantage and integrate these devices into tiny circuitry, aiming to enable new functions such as high-speed switches, in particular at the nanoscale technology. This review paper presents not only an historical overview of past endeavors, but also the remaining challenges to overcome. As part of these trials, one can mention complex design, fabrication, and characterization of smart nanoscale devices such as sensors and amplifiers, towards the next generations of circuitry and modules in nanotechnology. When compared to previous domain-limited text books, specialized technical manuals and focused scientific reviews, all published several decades ago, this up-to-date review paper presents important advantages and novelties: Large coverage of all domains and applications, clear orientation to the nanoscale dimensions, extended bibliography of almost one hundred fifty recent references, review of selected analytical models, summary tables and phenomena schematics. -

A Quantum Well Hall Effect Magnetovision System for Non-Destructive Testing

19th World Conference on Non-Destructive Testing 2016 A Quantum Well Hall Effect Magnetovision System for Non-Destructive Testing Chen-Wei LIANG 1, Ehsan AHMAD 1, Ertan BALABAN 1, James SEXTON 1 and Mohamed MISSOUS 1 1 School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering The University of Manchester, Sackville Street, Manchester M13 9Pl, UK Telephone: 0044 1613 064744 [email protected] Abstract. A novel magnetovision system was developed based on miniature, highly sensitive Quantum Well Hall Effect (QWHE) Sensors. This system consists of a handheld, portable 1616 QWHE sensors array, and an adjustable electromagnet, which can generate both DC and AC magnetic fields. The system has high spatial resolution due to the use of the small size sensors (QWHE) compared to conventional coils. By using a superheterodyne technique, magnetic fields in the range of nano to micro Tesla can be detected both for DC and AC operations, respectively. In DC measurements, this system can also be used as a MFL testing equipment, which can provide 2 dimensional graphical images results similar to MPI but without its inherent drawbacks. By using low frequency magnetic fields, non-magnetic materials such as aluminum, copper and stainless steels can also be examined allowing for deeper defects below the surface to be detected. By varying the frequency of the excitation magnetic field, different skin depth can be accessed and therefore the full thickness of the materials can be tested leading to 3 dimensional visualization of the positions and sizes of the defects. Finally, the system can be used in multiple sampling measurements to give better signal to noise ratios and in real time measurements for fast scan speed requirements. -

Quantum Well Hall Effect (QWHE) Sensors and Their Applications

Quantum Well Hall Effect (QWHE) sensors and their applications M. Missous, FREng University of Manchester PAGE 1 Quantum Well Hall Effect (QWHE) sensors and their applications RAL 12th March 2015 INTRODUCTION Magnetic sensors are fundamental to engineering and the physical sciences and are indispensable components in many systems. To date, virtually all magnetic sensors are either single elements or a small array of elements operated simultaneously (e.g. 3 component devices or small linear arrays). At best, present technology provides point, area average, or 1-Dimensional (assuming some form of linear translation) measurement of what is in reality a 4-D vector field (3- D space and time). The ability to capture magnetic field data in more than one dimension would be of real value and would represent a major advance in the state of the art. Two dimensional arrays of the type proposed here would allow direct high speed vision of magnetic fields, which could have an immediate impact on critical systems, especially those used for inspection or monitoring purposes. PAGE 2 Quantum Well Hall Effect (QWHE) sensors and their applications RAL 12th March 2015 Principle of Hall Effect Sensing When a conductor carrying a current (I) is placed in a magnetic field (B) and oriented so that the current and magnetic field are at right angles, an electric field is produced in the conductor at right angles to both current and magnetic field and produce a Bz I Hall Voltage (Vh) given by: t Jy Jx Vh = Kh . B . I Vh K 1 h t.n.e L w Where the sensitivity Kh is given by: Fig.