Issues Paper for the Development of a Climate Change Policy, Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Assessment January 2014

Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Regional Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project (RDVRP) Social Assessment Report January 2014 Central Planning Division, Ministry of Finance and Economic Plann ing 1st Floor, Administrative Centre, Bay Street, Kingstown, St.V incent and the Grenadines Tel.: 784-457-1746 ● Fax: 784-456-2430 E-mail: [email protected] St. Vincent and the Grenadines 2 Social Assessment Regional Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................... 5 Social Indicators ..................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 8 Objective of the Disaster Vulnerability Reduction Project ....................................................... 9 Socio-economic profile of St. Vincent and the Grenadines ............................................ 10 Country Description ................................................................................................................ 10 Weather and Climate .............................................................................................................. 10 Population Demographic Factors .......................................................................................... -

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines INTRODUCTION located on Saint Vincent, Bequia, Canouan, Mustique, and Union Island. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a multi-island Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, like most of state in the Eastern Caribbean. The islands have a the English-speaking Caribbean, has a British combined land area of 389 km2. Saint Vincent, with colonial past. The country gained independence in an area of 344 km2, is the largest island (1). The 1979, but continues to operate under a Westminster- Grenadines include 7 inhabited islands and 23 style parliamentary democracy. It is politically stable uninhabited cays and islets. All the islands are and elections are held every five years, the most accessible by sea transport. Airport facilities are recent in December 2010. Christianity is the Health in the Americas, 2012 Edition: Country Volume N ’ Pan American Health Organization, 2012 HEALTH IN THE AMERICAS, 2012 N COUNTRY VOLUME dominant religion, and the official language is fairly constant at 2.1–2.2 per woman. The crude English (1). death rate also remained constant at between 70 and In 2001 the population of Saint Vincent and 80 per 10,000 population (4). Saint Vincent and the the Grenadines was 102,631. In 2006, the estimated Grenadines has experienced fluctuations in its population was 100,271 and in 2009, it was 101,016, population over the past 20 years as a result of a decrease of 1,615 (1.6%) with respect to 2001. The emigration. According to the CIA World Factbook, sex distribution of the population in 2009 was almost the net migration rate in 2008 was estimated at 7.56 even, with males accounting for 50.5% (50,983) and migrants per 1,000 population (5). -

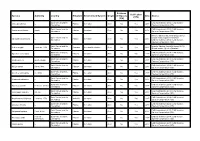

GRIIS Records of Verified Introduced and Invasive Species

Evidence Verification Species Authority Country Kingdom Environment/System Origin of Impacts Date Source (Y/N) (Y/N) Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Abrus precatorius L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Acacia auriculiformis Benth. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Saint Vincent and the Global Invasive Species Database. Adenanthera pavonina L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the Invasive Species Specialist Group (2015). Aedes aegypti Linnaeus, 1762 Animalia terrestrial/freshwater Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Global Invasive Species Database. Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Ageratum conyzoides L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia procera Benth. (Roxb.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Albizia saman (Jacq.) Merr. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Willd. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Allamanda cathartica L. Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). CABI Invasive Alpinia purpurata K.Schum. (Vieill.) Plantae terrestrial Alien No Yes 2017 Grenadines Species Compendium (ISC). Saint Vincent and the CAB International (2014). -

CONTENTS Is on Our Youth, the Leaders of Tomorrow

St. Vincent & the Grenadines Association of Toronto Inc. Quarterly Newsletter October 2007 5555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK This event was scheduled for late November but I have Greetings and best wishes to all members, friends and now learnt that it is postponed to March 1, 2008. We supporters of the Association. We thank you for your trust that this will be an opportunity for our young continued support as we strive to serve our community. people to look at the many opportunities that may become available to them. The last few months of the year are usually interesting ones for the Association as we look forward to As we look forward to the Annual General Meeting in wrapping up events held earlier in the year as well as January it would be useful if we would take some time planning for the ones to come including Independence out to prepare ourselves for it. Over the past few years Anniversary celebrations, the awarding of scholarships, the focus was just around the office of the president. the Children’s Christmas Party, the Christmas Hamper Getting persons to fill the other offices continue to be Project and to crown it off the preparation for the challenging and from time to time persons are forced to annual general meeting. accept these positions not merely because they are qualified to perform the role but because no one else On behalf of the executive I thank all those who have wanted the position. If we feel that there is need for volunteered their services and time so far to help us this organization to continue then we need to do what it accomplish what we have. -

SAINT VINCENT and the GRENADINES Pilot Program For

SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) PHASE ONE PROPOSAL 1 SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES PPCR PHASE 1 PROPOSAL Contents Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations .................................................................................. 5 Summary of Phase 1 Grant Proposal ................................................................................... 7 1.0 PROJECT BACKGROUND....................................................................................... 10 1.1 National Overview .................................................................................................. 11 1.1.1. Country Context ......................................................................................................... 11 2.0. Vulnerability Context .................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Climate .................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1 Precipitation ............................................................................................................... 14 2.1.2 Temperature ................................................................................................................ 15 2.1.3 Sea Level Rise ............................................................................................................. 15 2.1.4 Climate Extremes ....................................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

List of Projects- Stewardfish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations

List of projects- StewardFish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations On July 1, 2020 CANARI launched the call for applications for the USD20,000 StewardFish Microgrants Scheme for Caribbean Fisherfolk Organisations. The overall goal of the microgrant scheme is to provide support to Caribbean fisherfolk organisations for organisational strengthening initiatives that will enhance their capacity to participate in coastal and marine resources governance and management, including ecosystem stewardship. The call targeted the following five fisherfolk organisations participating in StewardFish: 1. Barbuda Fisherfolk Association – Antigua and Barbuda 2. Barbados National Union of Fisherfolk Organisations (BARNUFO) – Barbados 3. Guyana National Fisherfolk Organisation (GNFO)- Guyana 4. Saint Lucia Fisherfolk Cooperative Society Limited – Saint Lucia 5. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines National Fisherfolks Co-Operative Limited (SVGNFO) – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Each of the targeted fisherfolk organisations successfully submitted proposals to the microgrant scheme and were each awarded a USD4,000 microgrant for their projects which will run from November 2020 to April 2021. Table 1: List of StewardFish fisherfolk organisational strengthening projects Fisherfolk organisation Project title Project goal Barbados National iFish: Piloting an online To promote organisational strengthening Union of Fisherfolk platform for of BARNUFO to effectively mobilise Organizations organisational resources and build the capacity of its (BARNUFO) -

Saint Vincent & the Grenadines

Saint Vincent & the Grenadines – Our Experience With Energy Statitics Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is a multi-island state with St. Vincent being the main state and a chain of 32 small islands and cays, which receives almost 95% of the overall energy through imported oil products. Energy Policy The Government´s National Energy Policy: Published in March 2009, Stabilize and possibly reduce the provides the main guiding principles for energy consumption per capita in the the National Energy Policy for St. medium and long term; Vincent and the Grenadines. Strengthen the national economy by Guarantee a clean, reliable and reducing the dependence on import of affordable energy supply to customers; fossil fuels; Energy MATRIX The state-owned utility company VINLEC ELECTRICITY GENERATION operates mainly with internal combustion diesel engines and has an installed generation capacity of 58.3 megawatts (MW), of which 5.6 MW comes from three hydropower plants, (Cumberland 3.7 MW, Richmond 1.1 MW, and South Rivers 0.9 MW). with the remainder Name Location Year of Commissioning provided by diesel generators of which 42.41 MW are operated on the main island of St. Vincent with two diesel generating facilities, Cane Hall Power Plant Cane Hall 1975 Cane Hall (19.29 MW) and Lowman’s Bay (17.42 MW). Lowman's Bay Power Plant Lowman's Bay 2006 South Rivers Hydro Plant South Rivers 1952 HYDRO 22% Richmond Hydro plant Richmond 1962 Cumberland Hydro Plant Cumberland 1987 Bequia Power Plant Bequia 1990 PETROLEUM 78% Canouan Power Canouan 1994 Plant Union Island Power Plant Union Island 1993 Mayreau Power Mayreau 2003 Petroleum Hydro Plant Electricity consumption in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines by sector The Government of St. -

Deployment of an AWAC Off the East Coast of St Vincent, 2018-2019 Judith Wolf, Giles Williams and James Ayliffe

National Oceanography Centre Research & Consultancy Report No. 69 Deployment of an AWAC off the east coast of St Vincent, 2018-2019 Judith Wolf, Giles Williams and James Ayliffe October 2019 This report is part of the NOC-led project “Climate Change Impact Assessment: Ocean Modelling and Monitoring for the Caribbean CME states”, 2018-2019; under the Commonwealth Marine Economies (CME) Programme in the Caribbean. National Oceanography Centre Joseph Proudman Building 6 Brownlow St Liverpool L3 5DA UK email: [email protected] 1 2 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................. 5 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Background, aim and objectives of the study .......................................................... 7 1.2 Study Area – Saint Vincent and the Grenadines ..................................................... 7 1.3 Oceanographic description of the study area .......................................................... 9 2 Purchase of a wave gauge for St Vincent and Grenadines .......................................... 10 3 AWAC deployment ....................................................................................................... 11 3.1 July-October 2018................................................................................................. 14 3.2 January-March 2019 ............................................................................................ -

Meeting the Managua Challenge National

Meeting The Managua Challenge In November 2000, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) challenged governments of the Americas to accelerate their destruction of stockpiled antipersonnel mines ahead of the September 2001 meeting of States Parties to the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, which will be held in Managua, Nicaragua. It also urged the remaining signatories and non- signatories to fully join the treaty by September 2001 and for all States Parties to submit their initial transparency reports as required under Article 7 of the ban treaty. An update on this Managua Challenge shows significant progress made by many countries since November 2000 to meet the Challenge: Three signatories ratified: Chile, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Uruguay. Three States Parties have completed stockpile destruction: Ecuador, Honduras, and Peru. Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, and Uruguay destroyed some stockpiled mines. Six more States Parties have submitted their initial transparency reports:Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Paraguay. Two States Parties enacted national implementation legislation in 2001:Brazil and Trinidad and Tobago. One States Party will reduce the number of antipersonnel mines retained for training and development, as permitted under the Article 3 of the treaty: Peru will reduce the number from 9,526 to 5,578. Thirty of the thirty-five countries in the Americas region are State Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty. Since November 2000, there have been three ratifications: Uruguay (7 June 2001), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (1 August 2001), and Chile (10 September 2001). Three remaining signatories that have not ratified: Guyana, Haiti, and Suriname. Cuba and the United States remain the only two countries in the region that have not joined the Mine Ban Treaty. -

On Leaving and Joining Africanness Through Religion: the 'Black Caribs' Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons

Journal of Religion in Africa 37 (2007) 174-211 www.brill.nl/jra On Leaving and Joining Africanness Th rough Religion: Th e ‘Black Caribs’ Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons Paul Christopher Johnson University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Center for Afroamerican and African Studies, 505 S. State St./4700 Haven, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1045, USA [email protected] Abstract Garifuna religion is derived from a confluence of Amerindian, African and European anteced- ents. For the Garifuna in Central America, the spatial focus of authentic religious practice has for over two centuries been that of their former homeland and site of ethnogenesis, the island of St Vincent. It is from St Vincent that the ancestors return, through spirit possession, to join with their living descendants in ritual events. During the last generation, about a third of the population migrated to the US, especially to New York City. Th is departure created a new dia- sporic horizon, as the Central American villages left behind now acquired their own aura of ancestral fidelity and religious power. Yet New-York-based Garifuna are now giving attention to the African components of their story of origin, to a degree that has not occurred in homeland villages of Honduras. Th is essay considers the notion of ‘leaving’ and ‘joining’ the African diaspora by examining religious components of Garifuna social formation on St Vincent, the deportation to Central America, and contemporary processes of Africanization being initiated in New York. Keywords Garifuna, Black Carib, religion, diaspora, migration Introduction Not all religions, or families of religions, are of the diasporic kind. -

Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines National

Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines National Implementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants The Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Transformation, Forestry, Fisheries &Industry, & The Ministry of Health, Wellness and the Environment. Implementing the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in St. Vincent and the Grenadines 0 National Implementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants Published 2015 Prepared by the Government of St Vincent and the Grenadines As part of its obligation under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic pollutants National Focal Point Ministry of Health Wellness and the Environment Ministerial Building Kingstown Saint Vincent and the Grenadines 1 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ……………………………………………………………………...............4 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ………………………………………………………5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………………………….............7 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................11 1.1 History of Convention...................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Purpose and Structure of the NIP ...................................................................................13 1.3 Summary of POPs Issue .............................................................................................14 2.0 COUNTRY BASELINE .............................................................................................17