DHS-0A-Introduction English-Dec17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(A) No Person Or Corporation May Publish Or Reproduce in Any Manner., Without the Consent of the Committee on Research And-Graduate

RULES ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII NOV 8 1955 WITH REGARD TO THE REPRODUCTION OF MASTERS THESES (a) No person or corporation may publish or reproduce in any manner., without the consent of the Committee on Research and-Graduate. Study, a. thesis which has been submitted to the University in partial fulfillment of the require ments for an advanced degree, {b ) No individual or corporation or other organization may publish quota tions or excerpts from a graduate thesis without the consent of the author and of the Committee on Research and Graduate Study. UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY A STUDY CF SOCIO-ECONOMIC VALUES OF SAMOAN INTERMEDIATE u SCHOOL STUDENTS IN HAWAII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT CF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS JUNE 1956 Susan E. Hirsh Hawn. CB 5 H3 n o .345 co°“5 1 TABLE OP CONTENTS LIST GF TABUS ............................... iv CHAPTER. I. STATEMENT CP THE PROBLEM ........ 1 Introduction •••••••••••.•••••• 1 Th« Problem •••.••••••••••••••• 3 Methodology . »*••*«* i «#*•**• t * » 5 II. CONTEMPORARY SAMOA* THE CULTURE CP ORIGIN........ 10 Socio-Economic Structure 12 Soeic-Eoonosdo Chong« ••••••«.#•••«• 15 Socio-Economic Values? •••••••••••».. 17 Conclusions 18 U I . TBE SAIOAIS IN HAWAII» PEARL HARBOR AND LAXE . 20 Peerl Harbor 21 Lala ......... 24 Sumaary 28 IV. SELECTED BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS OP SAMOAN AND NON-SAMOAN INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL STUDENTS IN HAWAII . 29 Location of Residences of Students ••••••• -

Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change

The I and the We: Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change April K Henderson That the Samoan sense of self is relational, based on socio-spatial rela- tionships within larger collectives, is something of a truism—a statement of such obvious apparent truth that it is taken as a given. Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi, a former prime minister and current head of state of independent Sāmoa as well as an influential intellectual and essayist, has explained this Samoan relational identity: “I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a ‘tofi’ (an inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging” (Tui Atua 2003, 51). Elaborations of this relational self are consistent across the different political and geographical entities that Samoans currently inhabit. Par- ticipants in an Aotearoa/New Zealand–based project gathering Samoan perspectives on mental health similarly described “the Samoan self . as having meaning only in relationship with other people, not as an individ- ual. This self could not be separated from the ‘va’ or relational space that occurs between an individual and parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and other extended family and community members” (Tamasese and others 2005, 303). -

O Le Fogavaʻa E Tasi: Claiming Indigeneity Through Western Choral Practice in the Sāmoan Church

O Le Fogavaʻa e Tasi: Claiming Indigeneity through Western Choral practice in the Sāmoan Church Jace Saplan University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa Abstract Indigenous performance of Native Sāmoa has been constructed through colonized and decolonized systems since the arrival of western missionaries. Today, the western choral tradition is considered a cultural practice of Sāmoan Indigeniety that exists through intersections of Indigenous protocol and eurocentric performance practice. This paper will explore these intersections through an analysis of Native Sāmoan understandings of gender, Indigenous understandings and prioritizations of western vocal pedagogy, and the Indigenization of western choral culture. Introduction Communal singing plays a significant role in Sāmoan society. Much like in the greater sphere of Polynesia, contemporary Sāmoan communities are codified and bound together through song. In Sāmoa, sa (evening devotions), Sunday church services, and inter-village festivals add to the vibrant propagation of communal music making. These practices exemplify the Sāmoan values of aiga (family) and lotu (church). Thus, the communal nature of these activities contributes to the cultural value of community (Anae, 1998). European missionaries introduced hymn singing and Christian theology in the 1800s; this is acknowledged as a significant influence on the paralleled values of Indigenous thought, as both facets illustrate the importance of community (McLean, 1986). Today, the church continues to amplify the cultural importance of community, and singing remains an important activity to propagate these values. In Sāmoa, singing is a universal activity. The vast majority of Native Sāmoans grow up singing in the church choir, and many Indigenous schools require students to participate in the school choir. -

Introduction Navigating Spatial Relationships in Oceania

INTRODUCTION NAVIGATING SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN OCEANIA Richard Feinberg Department of Anthropology Kent State University Kent OH USA [email protected] Cathleen Conboy Pyrek Independent Scholar Rineyville, KY [email protected] Alex Mawyer Center for Pacific Island Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, HI USA [email protected] Recent decades have seen a revival of interest in traditional voyaging equipment and techniques among Pacific Islanders. At key points, the Oceanic voyaging revival came together with anthropological interests in cognition. This special issue explores that intersection as it is expressed in cognitive models of space, both at sea and on land. These include techniques for “wave piloting” in the Marshall Islands, wind compasses and their utilization as part of an inclusive navigational tool kit in the Vaeakau-Taumako region of the Solomon Islands; notions of ‘front’ and ‘back’ on Taumako and in Samoa, ideas of ‘above’ and ‘below’ in the Bougainville region of Papua New Guinea, spaces associated with the living and the dead in the Trobriand Islands, and the understanding of navi- gation in terms of neuroscience and physics. Keywords: cognition, navigation, Oceania "1 Recent decades have seen a revival of interest in traditional voyaging equipment and techniques among Pacific Islanders. That resurgence was inspired largely by the exploits of the Polynesian Voyaging Society and its series of successful expeditions, beginning with the 1976 journey of Hōkūle‘a, a performance-accurate replica of an early Hawaiian voyaging canoe, from Hawai‘i to Tahiti (Finney 1979, 1994; Kyselka 1987). Hōkūle‘a (which translates as ‘Glad Star’, the Hawaiian name for Arcturus) has, over the ensuing decades, sailed throughout the Polynesian Triangle and beyond. -

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project by Gary T. Kubota Copyright © 2018, Stories of Change – Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project The Kokua Hawaii Oral History interviews are the property of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project, and are published with the permission of the interviewees for scholarly and educational purposes as determined by Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. This material shall not be used for commercial purposes without the express written consent of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. With brief quotations and proper attribution, and other uses as permitted under U.S. copyright law are allowed. Otherwise, all rights are reserved. For permission to reproduce any content, please contact Gary T. Kubota at [email protected] or Lawrence Kamakawiwoole at [email protected]. Cover photo: The cover photograph was taken by Ed Greevy at the Hawaii State Capitol in 1971. ISBN 978-0-9799467-2-1 Table of Contents Foreword by Larry Kamakawiwoole ................................... 3 George Cooper. 5 Gov. John Waihee. 9 Edwina Moanikeala Akaka ......................................... 18 Raymond Catania ................................................ 29 Lori Treschuk. 46 Mary Whang Choy ............................................... 52 Clyde Maurice Kalani Ohelo ........................................ 67 Wallace Fukunaga .............................................. -

PACIFIC ISLANDS (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga)

PACIFIC ISLANDS (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga) Who is a Pacific Islander? The “Pacific Islands” is how we are described because of our geographic location, “Islands, geographically located in the Pacific Ocean”. Today, we will talk and share with educators, health experts, and community members of the three dominant Pacific Islander populations who live in San Mateo County, namely, Fijians, Samoans, and Tongans. PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS • When you talk about the Pacific Islands, you are talking about different Island Nations. • Different heads of countries, from kings to presidents, etc. Even different forms of government. • Some are independent countries, yet some are under the rule of a foreign power. PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS • Each Island Nation has their own language. • There is not one language that is used or understood by all Pacific Islanders. • There are some similarities but each island nation has it’s own unique characteristics. • Challenge in grouping the islands as just one group, “Pacific Islanders”. ISLANDS OF THE PACIFIC GREETINGS • From the Islands of Fiji “Bula Vinaka” • From the Islands of Samoa “Talofa Lava” • From the Kingdom of Tonga “Malo e Lelei” • From Chamorro “Hafa Adai” • From Tahiti “Ia Orana” • From Niue “Fakalofa atu” • From NZ Maoris “Tena Koe” • From Hawaii “Aloha” FIJI ISLANDS • Group of volcanic islands in the South Pacific, southwest of Honolulu. • Total of 322 islands, just over 100 are inhabited. • Biggest island Viti Levu, is the size of the “Big Island” of Hawaii. • Larger islands contain mountains as high as 4,000 feet. PEOPLE OF FIJI • Indigenous people are Fijians who are a mixture of Polynesian and Melanesian. -

Alaskan Eskimo and Polynesian Island Population Skeletal Anatomy: the "Pacific Arp Adox" Revisited Through Surface Area to Body Mass Comparisons

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 Alaskan Eskimo and Polynesian Island Population Skeletal Anatomy: The "Pacific arP adox" Revisited Through Surface Area to Body Mass Comparisons Wendy Nicole Leach The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Leach, Wendy Nicole, "Alaskan Eskimo and Polynesian Island Population Skeletal Anatomy: The "Pacific Paradox" Revisited Through Surface Area to Body Mass Comparisons" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 109. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALASKAN ESKIMO AND POLYNESIAN ISLAND POPULATION SKELETAL ANATOMY: THE “PACIFIC PARADOX” REVISITED THROUGH SURFACE AREA TO BODY MASS COMPARISONS By Wendy Nicole Leach B.A., Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2003 Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts In Anthropology The University of Montana Missoula, MT Autumn 2006 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School Dr. Noriko -

History, Myth and Polynesian Chieftainship: the Case of Rotuman Kings

History, myth and Polynesian chieftainship: the case of Rotuman kings Alan Howard The relationship between myth and history has become a central issue for anthropologists interested in the study of traditional societies, It has been brought to the fore by the work of Levi-Strauss on myth and the sharp contrast he draws between these alternative modes of organising discourse about social phenomena. The privileged position Levi-Strauss grants to myth has led to impassioned critiques and counter-critiques in volving Marxists, structuralists and a number of prominent European in tellectuals. The issue is perhaps especially important for Polynesianists since so much of the early literature in the region focused on oral nar ratives, recounting the deeds of ancestors whose characteristics ranged from godlike to mundanely human. In large part this body of literature was spawned by European fascination with the problem of Polynesian origins and migrations. Informants were incessantly asked where their ancestors had migrated from, triggering founding myths, stories of epic voyages, and the like, However, it is also apparent that Polynesians found myth a congenial medium for communication, and seem to have felt that they were disclosing truly important information about themselves when relating myths. In attempting to make sense out of Polynesian myths early scholars such as Abraham Fornander, S, Percy Smith and Te Rangi Hiroa treated them as ethnohistory, correct in their main features though possibly incorrect in detail (see, for example, Smith 1910:19), They viewed the narratives as reflective of actual events, some of which, particularly those occurring in the distant past, were overlain with mythical rhetoric. -

The Pacific Islands

American Universities Field Staff THIS FIELDSTAFF REPORT is one of a continuing series The on international affairs and major global issues of our time. Fieldstaff Reports have for twenty-five years American reached a group of readers--both academic and non- academic--who find them a useful source of firsthand Universities observation of political, economic, and social trends in foreign countries. Reports in the series are prepared by Field Staff writers who are full-time Associates of the American Universities Field Staff and occasionally by persons on P.O. Box 150, Hanover, NH 03755 leave from the organizations and universities that are the Field Staff's sponsors. Associates of the Field Staff are chosen for their ability to cut across the boundaries of the academic disciplines in order to study societies in their totality, and for their skill in collecting, reporting, and evaluating data. They combine long residence abroad with scholarly studies relating to their geographic areas of interest. Each Field Staff Associate returns to the United States periodically to lecture on the campuses of the consortium's member institutions. The American Universities Field Staff, Inc., founded in 1951 as a nonprofit organization of American educational institutions, engages in various international activities both at home and in foreign areas. These activities have a wide range and include writing on social and political change in the modern world, the making of documentary films (Faces of Change), and the organizing of seminars and teaching of students at the Center for Mediterranean Studies in Rome and the Center for Asian and Pacific Studies in Singapore. -

For American Samoans, As for Many Pacific Islanders, Traditional Land Tenure Provides Stability in a Fast-Changing World

Individual Land Tenure in American Sâmoa Merrily Stover For American Samoans, as for many Pacific Islanders, traditional land tenure provides stability in a fast-changing world. Yet even in countries where land tenure generally follows traditional practices, land is increas- ingly held by individual or small family units, rather than by large kin- based groups (see Ward and Kingdon 1995). The shift to individually owned lands in many Polynesian societies began with European settle- ment and colonial rule during the nineteenth century.1 Governments fre- quently imposed land registration and private ownership to secure land for settlers and facilitate development of commercial agriculture. Land registration also protected indigenous land rights and gave “order” to the land system. All too frequently, however, crippling land fragmentation, multiple ownership, and even land alienation have resulted. For the most part, such problems have not disturbed American Sâmoa, whose indigenous land tenure system is protected by law. However, like other Pacific Islanders, some American Samoans are choosing private land ownership, which contradicts the indigenous system. Where land is used primarily for residences and small gardens, the new practice gives land ownership to individuals, not groups, and grants owners the right to sell land to other Samoans and to will the land to their heirs. This essay explores this new practice—its geographical and historical roots. It tries to explain why American Samoans embrace this system, even though rhetoric and law support traditional land practices. The essay then briefly reviews land problems of some neighboring Polynesian groups. Finally, it explores factors that have allowed American Samoans to avoid some of those difficulties and suggests actions to maintain suc- cessful land tenure practices in this small island community. -

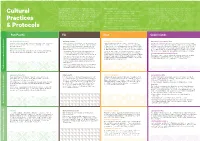

Cultural Practices & Protocols

Engagement that is meaningful is about respecting Advice may be about: By having a general understanding and knowing how to behave in these cultural practices and protocols. Pacific values common to • Formal ceremonies and knowing who and how to address situations shows Pacific communities respect and is a step in the right Cultural all Pacific Islands should always be considered when observing people and their roles in the appropriate manner direction for building good relationships. Below are a few examples any customs. However, among the different islands there are which demonstrate how practices vary from island to island. This is by • Use of island languages and translation by non-English speakers distinct differences in cultural practices, roles of family no means an exhaustive list but is merely intended to give you a basic Practices members, traditional dress and power structures. • Acknowledging and allowing time for elders to contribute introduction only. If you somehow forget everything you read here, • Taking time to observe protocols which uphold spirituality just remember to act respectfully and that it’s okay to ask if you don’t If you’re asked to attend a Pacific event or ceremony, through prayers. understand. it’s anticipated that you be accompanied and/or advised & Protocols by Pacific peoples who can help guide you. Note - A full list of basic greetings can be found at www.mpp.govt.nz - Tonga, Fiji and Samoa are the only Pacific countries that are commonly known for kava ceremony practices. Pan-Pacific Fiji Niue Cook Islands Role of spirituality in meetings Welcoming ceremony Welcoming ceremony and dance Haircutting ceremony (pakoti rouru) Pacific meetings or events usually begin and close with a prayer, and food is blessed Veiqaravi vakavanua is the traditional way to welcome an honoured guest Takalo was traditionally performed before going to war. -

Mitochondrial DNA Variation in the Fijian Archipelago by Diana A

Mitochondrial DNA variation in the Fijian Archipelago By Diana A. Taylor Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Alan J. Redd ________________________________ Dr. James H. Mielke ________________________________ Dr. Maria E. Orive Date Defended: April 5, 2012 The Thesis Committee for Diana A. Taylor certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Mitochondrial DNA variation in the Fijian Archipelago ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Alan J. Redd Date approved: April 18, 2012 ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to explore the evolutionary history of Fijians with respect to maternal ancestry. Geographically situated between Melanesia and Polynesia, Fiji has been a place of cultural exchange between Pacific Islanders for at least three thousand years. Traditionally, Fijians have been classified as Melanesians based on geography, culture, and skin pigmentation. However, Fijians share much in common linguistically, phenotypically, and genetically with Polynesians. Four questions motivated my research. First, are Fijians more Melanesian or Polynesian genetically? Second, is there a relationship between geography and genetic variation? Third, are Rotumans more similar to Fijians or Polynesians? And lastly, are Lau Islanders more similar to Fijians or Tongans? I used maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as my tool of investigation. In addition, I used various lines of anthropological evidence to synthesize my conclusions. I examined a sample of over 100 Fijians from five island populations, namely: Viti Levu, Kadavu, Vanua Levu, the Lau Islands, and Rotuma. In addition, my sample included two Melanesian and two Polynesian island populations.