Trochulus Oreinos (A.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arianta 6, 2018

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Arianta Jahr/Year: 2018 Band/Volume: 6 Autor(en)/Author(s): diverse Artikel/Article: Abstracts Talks Alpine and other land snails 11-27 ARIANTA 6 and correspond ecologically. For instance, the common redstart is a bird species breeding in the lowlands, whereas the black redstart is native to higher altitudes. Some species such as common swift and kestrel, which are originally adapted to enduring in rocky areas, even found a secondary habitat in the house facades and street canyons of towns and big cities. Classic rock dwellers include peregrine, eagle owl, rockthrush, snowfinch and alpine swift. The presentation focuses on the biology, causes of threat as well as conservation measures taken by the national park concerning the species golden eagle, wallcreeper, crag martin and ptarmigan. Birds breeding in the rocks might not be that high in number, but their survival is all the more fascinating and worth protecting as such! Abstracts Talks Alpine and other land snails Arranged in chronological order of the program Rangeconstrained cooccurrence simulation reveals little niche partitioning among rockdwelling Montenegrina land snails (Gastropoda: Clausiliidae) Zoltán Fehér1,2,3, Katharina JakschMason1,2,4, Miklós Szekeres5, Elisabeth Haring1,4, Sonja Bamberger1, Barna PállGergely6, Péter Sólymos7 1 Central Research Laboratories, Natural History Museum Vienna, Austria; [email protected] -

BMC Evolutionary Biology Biomed Central

BMC Evolutionary Biology BioMed Central Research article Open Access A species delimitation approach in the Trochulus sericeus/hispidus complex reveals two cryptic species within a sharp contact zone Aline Dépraz1, Jacques Hausser1 and Markus Pfenninger*2 Address: 1Department of Ecology and Evolution, Biophore – Quartier Sorge, University of Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland and 2Lab Centre, Biodiversity & Climate Research Centre, Biocampus Siesmayerstrasse, D-60054 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Email: Aline Dépraz - [email protected]; Jacques Hausser - [email protected]; Markus Pfenninger* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 21 July 2009 Received: 10 March 2009 Accepted: 21 July 2009 BMC Evolutionary Biology 2009, 9:171 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-171 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/9/171 © 2009 Dépraz et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Mitochondrial DNA sequencing increasingly results in the recognition of genetically divergent, but morphologically cryptic lineages. Species delimitation approaches that rely on multiple lines of evidence in areas of co-occurrence are particularly powerful to infer their specific status. We investigated the species boundaries of two cryptic lineages of the land snail genus Trochulus in a contact zone, using mitochondrial and nuclear DNA marker as well as shell morphometrics. Results: Both mitochondrial lineages have a distinct geographical distribution with a small zone of co-occurrence. -

Pulmonata, Helicidae) and the Systematic Position of Cylindrus Obtusus Based on Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Marker Sequences

© 2013 The Authors Accepted on 16 September 2013 Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research Published by Blackwell Verlag GmbH J Zoolog Syst Evol Res doi: 10.1111/jzs.12044 Short Communication 1Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES), University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; 2Central Research Laboratories, Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria; 33rd Zoological Department, Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria; 4Department of Integrative Zoology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; 5Department of Zoology, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary New data on the phylogeny of Ariantinae (Pulmonata, Helicidae) and the systematic position of Cylindrus obtusus based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA marker sequences 1 2,4 2,3 3 2 5 LUIS CADAHIA ,JOSEF HARL ,MICHAEL DUDA ,HELMUT SATTMANN ,LUISE KRUCKENHAUSER ,ZOLTAN FEHER , 2,3,4 2,4 LAURA ZOPP and ELISABETH HARING Abstract The phylogenetic relationships among genera of the subfamily Ariantinae (Pulmonata, Helicidae), especially the sister-group relationship of Cylindrus obtusus, were investigated with three mitochondrial (12S rRNA, 16S rRNA, Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I) and two nuclear marker genes (Histone H4 and H3). Within Ariantinae, C. obtusus stands out because of its aberrant cylindrical shell shape. Here, we present phylogenetic trees based on these five marker sequences and discuss the position of C. obtusus and phylogeographical scenarios in comparison with previously published results. Our results provide strong support for the sister-group relationship between Cylindrus and Arianta confirming previous studies and imply that the split between the two genera is quite old. The tree reveals a phylogeographical pattern of Ariantinae with a well-supported clade comprising the Balkan taxa which is the sister group to a clade with individuals from Alpine localities. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

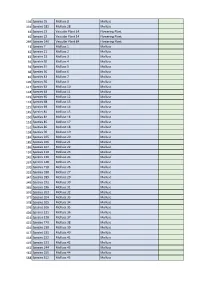

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

A St. Lawrence Iroquoian Village

STEWART: MCKEOWN SITE 17 Faunal Findings from Three Longhouses of the McKeown Site (BeFv-1), A St. Lawrence Iroquoian Village. Frances L. Stewart The 4,536 faunal specimens excavated from three sub-samples from the individual houses were kept houses of the McKeown Site, a St. Lawrence separate to allow a comparison of animal usage Iroquoian village near Maynard, Ontario were between the houses. Related to this was the testing of studied to determine the subsistence pattern of the the hypothesis that foodstuffs might have varied over people living there around 1500 A.D. time. Unusual occurrences in the material were noted From the remains from seven classes of animals, and explanations were offered for the faunal findings, the seasonal exploitation pattern of the villagers was with comparisons to other Iroquoian sites. reconstructed. Of significance to faunal analyses in This paper begins with brief descriptions of the general was the variation in the faunal refuse among techniques of excavation, the site and its the three houses. Of specific interest to Iroquoian environment, and the methods of faunal analysis. studies was the scarcity of dog remains and the After the presentation of the faunal data the results relatively high number of black bear elements. are discussed. The faunal details are ordered from most to least frequently identified remains. The paper ends with a few concluding remarks. Introduction Excavation of exploratory trenches revealed the village's palisades and associated ditches and The McKeown Site (BeFv-1), located on Lot 11, removal of the plough zone with bulldozers and Concession 2, Augusta Township, Grenville County, shovels uncovered twenty-three longhouses. -

Molluscs of the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area

Molluscs of the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area S a b i n e F ISCHER & M i c h a e l D UDA Abstract: Research in the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area (DWA) in the southwest of Lower Austria is mainly concerned with the inventory of flora, fauna and habitats, interdisciplinary monitoring and studies on ecological disturbances and process dynamics. During a four-year qualitative study of non-marine molluscs, 96 sites within the DWA and nearby nature reserves were sampled in cooperation with the “Alpine Land Snails Working Group” located at the Natural History Museum of Vienna. Altogether, 84 taxa were recorded (72 land snails, 12 water snails and mussels) including four endemics and seven species listed in the Austrian Red List of Molluscs. A reference collection (empty shells) of molluscs, which is stored at the DWA administration, was created. This project was the first systematic survey of mollusc fauna in the DWA. Further sampling might provide additional information in the future, particularly for Hydrobiidae in springs and caves, where detailed analyses (e.g. anatomical and genetic) are needed. Key words: Wilderness Dürrenstein, Primeval forest, Benign neglect, Non-intervention management, Mollusca, Snails, Alpine endemics. Introduction manifold species living in the wilderness area – many of them “refugees”, whose natural habitats have almost In concordance with the IUCN guidelines, research is disappeared in today’s over-cultivated landscape. mandatory for category I wilderness areas. However, it may not disturb the natural habitats and communities of the nature reserve. Research in the Dürrenstein The Dürrenstein Wilderness Area Wilderness Area (DWA) focuses on providing invento- (DWA) ries of flora and fauna, on interdisciplinary monitoring The Dürrenstein Wilderness Area (DWA) was as well as on ecological disturbances and process dynamics. -

Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Helicidae)

Ruthenica, 2012, vol. 22, No. 2: 93-100. © Ruthenica, 2012 Published October 20, 2012 http: www.ruthenica.com On the origin of Cochlopupa (= Cylindrus auct.) obtusa (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Helicidae) Anatoly A. SCHILEYKO A.N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninsky Prospect 33, 119071, Moscow, RUSSIA; e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Land snail Cochlopupa obtusa (Drapar- py) is widely-used for the species of Helicidae dur- naud, 1805) is an endemic of Eastern Alps. The mol- ing many tens of years. Unfortunately, this name is lusk has very unusual for helicids pupilloid shell, but invalid because it is junior homonym of Cylindrus its reproductive tract is quite typical for the subfamily Batsch, 1789 (Gastropoda, Conidae) (type species Ariantinae (Helicidae). Neither this species nor any Conus textile Linnaeus, 1758, by subsequent desig- similar forms are totally absent in fossil deposits (the nation Dubois and Bour, 2010). earliest records of C. obtusa conventionally dated by the “pre-Pleistocene”). According to suggested hy- At the same time the generic name Cylindrus pothesis, this species is very young and was formed Fitzinger is a junior objective synonym of Cochlo- within the existing area at the end of Würm glaciation pupa Jan, 1830 with type species Pupa obtusa due to mutation of some representative of Ariantinae. Draparnaud, 1805 (by monotypy). Thus, the correct binomen for the representative of Helicidae in ac- cordance with the rules of the ICZN must be Coch- Introduction lopupa obtusa (Draparnaud, 1805). Some years ago I have written that I directed a In Eastern Alps, on the territory of Austria, lives petition to the International Commission on Zoo- a very peculiar species of the Helicidae family – logical Nomenclature where I ask to conserve the Cochlopupa obtusa (Draparnaud, 1805) (Fig. -

Why Do Snails Have Hairs? a Bayesian Inference of Character Evolution Markus Pfenninger*1, Magda Hrabáková2, Dirk Steinke3 and Aline Dèpraz4

BMC Evolutionary Biology BioMed Central Research article Open Access Why do snails have hairs? A Bayesian inference of character evolution Markus Pfenninger*1, Magda Hrabáková2, Dirk Steinke3 and Aline Dèpraz4 Address: 1Abteilung Ökologie & Evolution, J.W. Goethe-Universität, BioCampus Siesmayerstraße, 60054 Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2Deparment of Zoology, Charles University, Viniènà 7, 128 44 Praha 2, Czech Republic, 3Department of Biology, University of Konstanz, Postbox 5560 M618, 78457 Konstanz, Germany and 4Département d'Ecologie et Evolution, Université de Lausanne, Bâtiment de Biologie, Dorigny, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Email: Markus Pfenninger* - [email protected]; Magda Hrabáková - [email protected]; Dirk Steinke - [email protected]; Aline Dèpraz - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 04 November 2005 Received: 14 July 2005 Accepted: 04 November 2005 BMC Evolutionary Biology 2005, 5:59 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-59 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/5/59 © 2005 Pfenninger et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Costly structures need to represent an adaptive advantage in order to be maintained over evolutionary times. Contrary to many other conspicuous shell ornamentations of gastropods, the haired shells of several Stylommatophoran land snails still lack a convincing adaptive explanation. In the present study, we analysed the correlation between the presence/absence of hairs and habitat conditions in the genus Trochulus in a Bayesian framework of character evolution. -

Plicuteria Lubomirski (Œlósarski, 1881)

Folia Malacol. 21(2): 91–97 http://dx.doi.org/10.12657/folmal.021.010 PLICUTERIA LUBOMIRSKI (ŒLÓSARSKI, 1881) (GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: HYGROMIIDAE), A FORGOTTEN ELEMENT OF THE ROMANIAN MOLLUSC FAUNA, WITH NOTES ON THE CORRECT SPELLING OF ITS NAME 1,* 2 3 4 BARNA PÁLL-GERGELY ,ROLAND FARKAS ,TAMÁS DELI ,FRANCISCO WELTER-SCHULTES 1 Department of Biology, Shinshu University, Matsumoto 390-8621, Japan (e-mail: [email protected]) 2 Aggtelek National Park Directorate, Tengerszem oldal 1, H-3758 Jósvafõ, Hungary (e-mail: [email protected]) 3 Békés Megyei Múzeumok Igazgatósága, Gyulai u 1., H-5600 Békéscsaba, Hungary (e-mail: [email protected]) 4 Zoologisches Institut, Berliner Strasse 28, 37073 Göttingen, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]) * corresponding author ABSTRACT: In this paper two new localities of the hygromiid land snail Plicuteria lubomirski (Œlósarski, 1881) are reported from Romania (Suceava and Harghita Counties). Its presence at the Lacu Roºu (Gyilkos-tó) area rep- resents the southeasternmost occurrence of the species. The only sample of P. lubomirski hitherto reported from Romania (leg. JICKELI in 1888 at Borsec Bai) seems to be lost from museum collections. The northern Carpathian distributional type is suggested for the species. The nomenclatural problem regarding the spelling of the specific name (i.e. lubomirskii or lubomirski) is discussed. The original, but less frequently used spelling (lubomirski) is suggested based on our understanding of the regulations of the ICZN. KEY WORDS: Carpathian species, faunistics, biogeography, Trochulus, anatomy INTRODUCTION Plicuteria lubomirski (Œlósarski, 1881) (often referred Umgebung des Bades Borszék” (=around Borsec Bai). to as Trochulus) is a Carpathian species reported from This record was later mentioned by SOÓS (1943) and Austria (KLEMM 1973, but also see REISCHÜTZ & GROSSU (1983). -

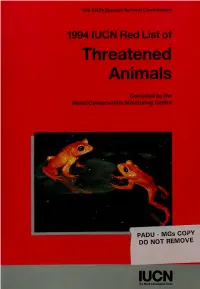

1994 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals

The lUCN Species Survival Commission 1994 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre PADU - MGs COPY DO NOT REMOVE lUCN The World Conservation Union lo-^2^ 1994 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals lUCN WORLD CONSERVATION Tile World Conservation Union species susvival commission monitoring centre WWF i Suftanate of Oman 1NYZ5 TTieWlLDUFE CONSERVATION SOCIET'' PEOPLE'S TRISr BirdLife 9h: KX ENIUNGMEDSPEaES INTERNATIONAL fdreningen Chicago Zoulog k.J SnuicTy lUCN - The World Conservation Union lUCN - The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organisations in a unique world partnership: some 770 members in all, spread across 123 countries. - As a union, I UCN exists to serve its members to represent their views on the world stage and to provide them with the concepts, strategies and technical support they need to achieve their goals. Through its six Commissions, lUCN draws together over 5000 expert volunteers in project teams and action groups. A central secretariat coordinates the lUCN Programme and leads initiatives on the conservation and sustainable use of the world's biological diversity and the management of habitats and natural resources, as well as providing a range of services. The Union has helped many countries to prepare National Conservation Strategies, and demonstrates the application of its knowledge through the field projects it supervises. Operations are increasingly decentralised and are carried forward by an expanding network of regional and country offices, located principally in developing countries. I UCN - The World Conservation Union seeks above all to work with its members to achieve development that is sustainable and that provides a lasting Improvement in the quality of life for people all over the world. -

An Anomaly of the Reproductive Organs in Trochulus Hispidus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Hygromiidae)

Vol. 20(1): 39–41 doi: 10.2478/v10125-012-0002-6 AN ANOMALY OF THE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS IN TROCHULUS HISPIDUS (LINNAEUS, 1758) (GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: HYGROMIIDAE) 1 2 MA£GORZATA PROÆKÓW ,EL¯BIETA KUZNIK-KOWALSKA 1Museum of Natural History, Wroc³aw University, Sienkiewicza 21, 50-335 Wroc³aw, Poland (e-mail: [email protected]) 2Department of Invertebrate Systematics and Ecology, Institute of Biology, Wroc³aw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Ko¿uchowska 5b, 51-631 Wroc³aw, Poland ABSTRACT: A specimen of Trochulus hispidus from Buchenbach, Germany, had its male and female parts of the reproductive system completely separated. The female part lacked auxiliary organs. The male part opened into the genital atrium, but the vas deferens was blind-ended in a way precluding sperm transfer. KEY WORDS: land snail, Trochulus hispidus, Hygromiidae, reproductive organs, anomaly Anomalies of the reproductive organs have been did not differ from the remaining specimens from recorded in several species of pulmonate land snails. that site. On dissection, we found the reproductive or- The vast majority involves the male part of the repro- gans to be abnormal. Two separate parts could be dis- ductive system, while female organs are usually nor- tinguished. One was blind-ended and consisted of the mally developed. Repetition of the penis is the most gonad, the hermaphrodite duct, the albumen gland common anomaly and has been reported in Helix and the spermoviduct which passed into the short pomatia Linnaeus, 1758 (PARAVICINI 1898, PÉGOT spermathecal duct ending with the spermatheca (Fig. 1900, ASHWORTH 1907, LATTMANN 1967), Cernuella 1A). -

High Population Differentiation in the Rock-Dwelling Land Snail (Trochulus Caelatus) Endemic to the Swiss Jura Mountains

Conserv Genet (2010) 11:1265–1271 DOI 10.1007/s10592-009-9956-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE High population differentiation in the rock-dwelling land snail (Trochulus caelatus) endemic to the Swiss Jura Mountains Sylvain Ursenbacher Æ Caren Alvarez Æ Georg F. J. Armbruster Æ Bruno Baur Received: 9 February 2009 / Accepted: 24 June 2009 / Published online: 14 July 2009 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 Abstract Understanding patterns of genetic structure is Introduction fundamental for developing successful management pro- grammes for isolated populations of threatened species. The fragmentation of natural habitat is generally consid- Trochulus caelatus is a small terrestrial snail endemic to ered to be a major threat to many species. Population calcareous rock cliffs in the Northwestern Swiss Jura genetic theory predicts that the isolation of small popula- Mountains. Eight microsatellite loci were used to assess the tions lead to a reduction of genetic diversity. Human effect of habitat isolation on genetic population structure activities are often the main causes of habitat fragmenta- and gene flow among nine populations occurring on dis- tion, but geographical processes and/or specific habitat tinct cliffs. We found a high genetic differentiation among requirements may also contribute to natural segregation of populations (mean FST = 0.254) indicating that the popu- populations. Species with limited dispersal ability partic- lations are strongly isolated. Both allelic richness and ularly suffer from isolation, which may lead to a marked effective population size were positively correlated with genetic divergence among populations (e.g. Conner and the size of the cliffs. Our findings support the hypothesis Hartl 2004).