GEOG 300 Atmospheric Pressure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11 General Circulation

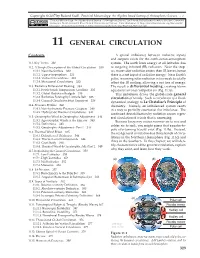

Copyright © 2017 by Roland Stull. Practical Meteorology: An Algebra-based Survey of Atmospheric Science. v1.02 “Practical Meteorology: An Algebra-based Survey of Atmospheric Science” by Roland Stull is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. View this license at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-sa/4.0/ . This work is available at https://www.eoas.ubc.ca/books/Practical_Meteorology/ 11 GENERAL CIRCULATION Contents A spatial imbalance between radiative inputs and outputs exists for the earth-ocean-atmosphere 11.1. Key Terms 330 system. The earth loses energy at all latitudes due 11.2. A Simple Description of the Global Circulation 330 to outgoing infrared (IR) radiation. Near the trop- 11.2.1. Near the Surface 330 ics, more solar radiation enters than IR leaves, hence 11.2.2. Upper-troposphere 331 there is a net input of radiative energy. Near Earth’s 11.2.3. Vertical Circulations 332 poles, incoming solar radiation is too weak to totally 11.2.4. Monsoonal Circulations 333 offset the IR cooling, allowing a net loss of energy. 11.3. Radiative Differential Heating 334 The result is differential heating, creating warm 11.3.1. North-South Temperature Gradient 335 equatorial air and cold polar air (Fig. 11.1a). 11.3.2. Global Radiation Budgets 336 This imbalance drives the global-scale general 11.3.3. Radiative Forcing by Latitude Belt 338 circulation of winds. Such a circulation is a fluid- 11.3.4. General Circulation Heat Transport 338 dynamical analogy to Le Chatelier’s Principle of 11.4. -

Unit 11 Sound Speed of Sound Speed of Sound Sound Can Travel Through Any Kind of Matter, but Not Through a Vacuum

Unit 11 Sound Speed of Sound Speed of Sound Sound can travel through any kind of matter, but not through a vacuum. The speed of sound is different in different materials; in general, it is slowest in gases, faster in liquids, and fastest in solids. The speed depends somewhat on temperature, especially for gases. vair = 331.0 + 0.60T T is the temperature in degrees Celsius Example 1: Find the speed of a sound wave in air at a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius. v = 331 + (0.60) (20) v = 331 m/s + 12.0 m/s v = 343 m/s Using Wave Speed to Determine Distances At normal atmospheric pressure and a temperature of 20 degrees Celsius, speed of sound: v = 343m / s = 3.43102 m / s Speed of sound 750 mi/h Speed of light 670 616 629 mi/h c = 300,000,000m / s = 3.00 108 m / s Delay between the thunder and lightning Example 2: The thunder is heard 3 seconds after the lightning seen. Find the distance to storm location. The speed of sound is 345 m/s. distance = v t = (345m/s)(3s) = 1035m Example 3: Another phenomenon related to the perception of time delays between two events is an echo. In a canyon, an echo is heard 1.40 seconds after making the holler. Find the distance to the canyon wall (v=345m/s) distanceround trip = vt = (345 m/s )( 1.40 s) = 483 m d= 484/2=242m Applications: Sonar, Ultrasound, and Medical Imaging • Ultrasound or ultrasonography is a medical imaging technique that uses high frequency sound waves and their echoes. -

Atmospheric Cold Front-Generated Waves in the Coastal Louisiana

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Atmospheric Cold Front-Generated Waves in the Coastal Louisiana Yuhan Cao 1 , Chunyan Li 2,* and Changming Dong 1,3,* 1 School of Marine Sciences, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences, College of the Coast and Environment, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA 3 Southern Laboratory of Ocean Science and Engineering (Zhuhai), Zhuhai 519000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (C.D.); Tel.: +1-225-578-2520 (C.L.); +86-025-58695733 (C.D.) Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 9 November 2020; Published: 11 November 2020 Abstract: Atmospheric cold front-generated waves play an important role in the air–sea interaction and coastal water and sediment transports. In-situ observations from two offshore stations are used to investigate variations of directional waves in the coastal Louisiana. Hourly time series of significant wave height and peak wave period are examined for data from 2004, except for the summer time between May and August, when cold fronts are infrequent and weak. The intra-seasonal scale variations in the wavefield are significantly affected by the atmospheric cold frontal events. The wave fields and directional wave spectra induced by four selected cold front passages over the coastal Louisiana are discussed. It is found that significant wave height generated by cold fronts coming from the west change more quickly than that by other passing cold fronts. The peak wave direction rotates clockwise during the cold front events. -

A Review of Ocean/Sea Subsurface Water Temperature Studies from Remote Sensing and Non-Remote Sensing Methods

water Review A Review of Ocean/Sea Subsurface Water Temperature Studies from Remote Sensing and Non-Remote Sensing Methods Elahe Akbari 1,2, Seyed Kazem Alavipanah 1,*, Mehrdad Jeihouni 1, Mohammad Hajeb 1,3, Dagmar Haase 4,5 and Sadroddin Alavipanah 4 1 Department of Remote Sensing and GIS, Faculty of Geography, University of Tehran, Tehran 1417853933, Iran; [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (M.H.) 2 Department of Climatology and Geomorphology, Faculty of Geography and Environmental Sciences, Hakim Sabzevari University, Sabzevar 9617976487, Iran 3 Department of Remote Sensing and GIS, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran 1983963113, Iran 4 Department of Geography, Humboldt University of Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, 10099 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (D.H.); [email protected] (S.A.) 5 Department of Computational Landscape Ecology, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research UFZ, 04318 Leipzig, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +98-21-6111-3536 Received: 3 October 2017; Accepted: 16 November 2017; Published: 14 December 2017 Abstract: Oceans/Seas are important components of Earth that are affected by global warming and climate change. Recent studies have indicated that the deeper oceans are responsible for climate variability by changing the Earth’s ecosystem; therefore, assessing them has become more important. Remote sensing can provide sea surface data at high spatial/temporal resolution and with large spatial coverage, which allows for remarkable discoveries in the ocean sciences. The deep layers of the ocean/sea, however, cannot be directly detected by satellite remote sensors. -

Dicionarioct.Pdf

McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Earth Science Second Edition McGraw-Hill New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2003 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be repro- duced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-141798-2 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-141045-7 All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw- Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decom- pile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Download Demo

For DLP, Current Affairs Magazine & Test Series related regular updates, follow us on www.facebook.com/drishtithevisionfoundation www.twitter.com/drishtiias CONTENTS UNIT-I : GEOMORPHOLOGY 1. Introduction to Geography 3-5 2. Origin of Universe, Earth & Life 6-11 3. Our Earth 12-29 4. Rocks & Minerals 30-32 5. Weathering, Mass Movement & Erosion 33-40 6. Landforms 41-51 7. Soil 52-62 UNIT-II : CLIMATOLOGY 8. Weather & Climate 65-67 9. Composition & Structure of Atmosphere 68-71 10. Distribution of Temperature & Heat Budget 72-80 11. Pressure & Wind Systems 81-100 12. Condensation & Precipitation 101-108 13. Classification of Climate 109-114 UNIT-III : OCEANOGRAPHY 14. Oceans 117-130 15. Oceanic Resources 131-136 UNIT-IV : HUMAN & ECONOMIC GEOGRAPHY 16. Population 139-154 17. Human Development 155-160 18. Settlement & Migration 161-173 19. Agriculture 174-201 20. Resources of the World 202-224 21. Location of Industries 225-247 22. Transport 248-254 Previous Years’ UPSC Questions (Solved) 255-261 Practice Questions 262 Pressure & Wind Systems 11 Chapter The weight of a column of air contained in a unit area from the mean sea level to the top of the atmosphere is called the air or atmospheric pressure. The atmospheric pressure is expressed in units of millibar. At sea level the average atmospheric pressure is 1,013.2 millibar. Due to gravity, the air at the surface is denser and hence has higher pressure. Air pressure is measured with the help of a mercury barometer or the aneroid barometer. The pressure decreases with height. At any elevation it varies from place to place and its variation is the primary cause of air motion, i.e. -

Physical Geography Chapter 5: Atmospheric Pressure, Winds, Circulation Patterns

Physical Geography Chapter 5: Atmospheric Pressure, Winds, Circulation Patterns Torricelli – 1643- first Mercury barometer (76 cm, 29.92 in) – measures response to pressure Pressure – millibars- 1013.2 mb, will cause Hg to rise in tube Unequal heating of Earth’s surface is responsible for differences in pressure to! Variations in Atmospheric Pressure 1. Vertical Variations – increase in elevation, less air pressure Mt. Everest – 8848 m (or 29, 028 ft) – 1/3 pressure 2. Horizontal Variations a. Thermal (determined by T) Warm air is less dense – it rises away from the surface at the equator b. Dynamic: Air from the tropics moves northward and then to the east due to the Coryolis Effect. It collects at this latitude, increasing pressure at the surface. Basic Pressure Systems 1. Low – cyclone – converging air pressure decreases 2. High – anticyclone – Divergins air pressure increases Wind Isobars- line of equal pressure Pressure Gradient - significant difference in pressure Wind- horizontal movement of air in response to differences in pressure ¾ Responsible for moving heat toward poles ¾ 38° Lat and lower: radiation surplus If Earth did not rotate, and if there wasno friction between moving air and the Earth’s surface, the air would flow in a straight line from areas of higher pressure to areas of low pressure. Of course, this is not true, the Earth rotates and friction exists: and wind is controlled by three major factors: 1) PGF- Pressure is measured by barometer 2) Coriolis Effect 3) Friction 1) Pressure Gradient Force (PGF) Pressure differences create wind, and the greater these differences, the greater the wind speed. -

Diving Air Compressor - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Diving Air Compressor from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/8/2014 Diving air compressor - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Diving air compressor From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A diving air compressor is a gas compressor that can provide breathing air directly to a surface-supplied diver, or fill diving cylinders with high-pressure air pure enough to be used as a breathing gas. A low pressure diving air compressor usually has a delivery pressure of up to 30 bar, which is regulated to suit the depth of the dive. A high pressure diving compressor has a delivery pressure which is usually over 150 bar, and is commonly between 200 and 300 bar. The pressure is limited by an overpressure valve which may be adjustable. A small stationary high pressure diving air compressor installation Contents 1 Machinery 2 Air purity 3 Pressure 4 Filling heat 5 The bank 6 Gas blending 7 References 8 External links A small scuba filling and blending station supplied by a compressor and Machinery storage bank Diving compressors are generally three- or four-stage-reciprocating air compressors that are lubricated with a high-grade mineral or synthetic compressor oil free of toxic additives (a few use ceramic-lined cylinders with O-rings, not piston rings, requiring no lubrication). Oil-lubricated compressors must only use lubricants specified by the compressor's manufacturer. Special filters are used to clean the air of any residual oil and water(see "Air purity"). Smaller compressors are often splash lubricated - the oil is splashed around in the crankcase by the impact of the crankshaft and connecting A low pressure breathing air rods - but larger compressors are likely to have a pressurized lubrication compressor used for surface supplied using an oil pump which supplies the oil to critical areas through pipes diving at the surface control point and passages in the castings. -

Use of Synthetic Aperture Radar in Finescale Surface Analysis of Synoptic-Scale Fronts at Sea

JUNE 2005 YOUNG ET AL. 311 Use of Synthetic Aperture Radar in Finescale Surface Analysis of Synoptic-Scale Fronts at Sea G. S. YOUNG Department of Meteorology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania T. D. SIKORA Department of Oceanography, United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland N. S. WINSTEAD Applied Physics Laboratory, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland (Manuscript received 8 March 2004, in final form 6 December 2004) ABSTRACT The viability of synthetic aperture radar (SAR) as a tool for finescale marine meteorological surface analyses of synoptic-scale fronts is demonstrated. In particular, it is shown that SAR can reveal the presence of, and the mesoscale and microscale substructures associated with, synoptic-scale cold fronts, warm fronts, occluded fronts, and secluded fronts. The basis for these findings is the analysis of some 6000 RADARSAT-1 SAR images from the Gulf of Alaska and from off the east coast of North America. This analysis yielded 158 cases of well-defined frontal signatures: 22 warm fronts, 37 cold fronts, 3 stationary fronts, 32 occluded fronts, and 64 secluded fronts. The potential synergies between SAR and a range of other data sources are discussed for representative fronts of each type. 1. Introduction sensor can meet all of the analyst’s needs. It is only by using the available sensors synergistically that a fine- Finescale surface analysis of synoptic-scale weather scale marine surface analysis may be prepared. Note systems is a challenging undertaking in the best of cir- C-MAN in Table 1 refers to Coastal–Marine Auto- cumstances, but has proven particularly difficult at sea mated Network. -

Air Pressure and Wind

Air Pressure We know that standard atmospheric pressure is 14.7 pounds per square inch. We also know that air pressure decreases as we rise in the atmosphere. 1013.25 mb = 101.325 kPa = 29.92 inches Hg = 14.7 pounds per in 2 = 760 mm of Hg = 34 feet of water Air pressure can simply be measured with a barometer by measuring how the level of a liquid changes due to different weather conditions. In order that we don't have columns of liquid many feet tall, it is best to use a column of mercury, a dense liquid. The aneroid barometer measures air pressure without the use of liquid by using a partially evacuated chamber. This bellows-like chamber responds to air pressure so it can be used to measure atmospheric pressure. Air pressure records: 1084 mb in Siberia (1968) 870 mb in a Pacific Typhoon An Ideal Ga s behaves in such a way that the relationship between pressure (P), temperature (T), and volume (V) are well characterized. The equation that relates the three variables, the Ideal Gas Law , is PV = nRT with n being the number of moles of gas, and R being a constant. If we keep the mass of the gas constant, then we can simplify the equation to (PV)/T = constant. That means that: For a constant P, T increases, V increases. For a constant V, T increases, P increases. For a constant T, P increases, V decreases. Since air is a gas, it responds to changes in temperature, elevation, and latitude (owing to a non-spherical Earth). -

Aircraft Performance: Atmospheric Pressure

Aircraft Performance: Atmospheric Pressure FAA Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge Chap 10 Atmosphere • Envelope surrounds earth • Air has mass, weight, indefinite shape • Atmosphere – 78% Nitrogen – 21% Oxygen – 1% other gases (argon, helium, etc) • Most oxygen < 35,000 ft Atmospheric Pressure • Factors in: – Weather – Aerodynamic Lift – Flight Instrument • Altimeter • Vertical Speed Indicator • Airspeed Indicator • Manifold Pressure Guage Pressure • Air has mass – Affected by gravity • Air has weight Force • Under Standard Atmospheric conditions – at Sea Level weight of atmosphere = 14.7 psi • As air become less dense: – Reduces engine power (engine takes in less air) – Reduces thrust (propeller is less efficient in thin air) – Reduces Lift (thin air exerts less force on the airfoils) International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) • Standard atmosphere at Sea level: – Temperature 59 degrees F (15 degrees C) – Pressure 29.92 in Hg (1013.2 mb) • Standard Temp Lapse Rate – -3.5 degrees F (or 2 degrees C) per 1000 ft altitude gain • Upto 36,000 ft (then constant) • Standard Pressure Lapse Rate – -1 in Hg per 1000 ft altitude gain Non-standard Conditions • Correction factors must be applied • Note: aircraft performance is compared and evaluated with respect to standard conditions • Note: instruments calibrated for standard conditions Pressure Altitude • Height above Standard Datum Plane (SDP) • If the Barometric Reference Setting on the Altimeter is set to 29.92 in Hg, then the altitude is defined by the ISA standard pressure readings (see Figure 10-2, pg 10-3) Density Altitude • Used for correlating aerodynamic performance • Density altitude = pressure altitude corrected for non-standard temperature • Density Altitude is vertical distance above sea- level (in standard conditions) at which a given density is to be found • Aircraft performance increases as Density of air increases (lower density altitude) • Aircraft performance decreases as Density of air decreases (higher density altitude) Density Altitude 1. -

Barry R.G., Chorley R.J. Atmosphere, Weather and Climate (8Ed

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Atmosphere, Weather and Climate 11 12 13 14 15 16 Atmosphere, Weather and Climate is the essential I updated analysis of atmospheric composition, 17 introduction to weather processes and climatic con- weather and climate in middle latitudes, atmospheric 18 ditions around the world, their observed variability and oceanic motion, tropical weather and climate, 19 and changes, and projected future trends. Extensively and small-scale climates 20 revised and updated, this eighth edition retains its I chapter on climate variability and change has been 21 popular tried and tested structure while incorporating completely updated to take account of the findings of 22 recent advances in the field. From clear explanations the IPCC 2001 scientific assessment 23 of the basic physical and chemical principles of the 24 atmosphere, to descriptions of regional climates and I new more attractive and accessible text design 25 their changes, Atmosphere, Weather and Climate I new pedagogical features include: learning objec- 26 presents a comprehensive coverage of global meteor- tives at the beginning of each chapter and discussion 27 ology and climatology. In this new edition, the latest points at their ending, and boxes on topical subjects 28 scientific ideas are expressed in a clear, non- and twentieth-century advances in the field. 29 mathematical manner. 30 Roger G. Barry is Professor of Geography, University 31 New features include: of Colorado at Boulder, Director of the World Data 32 Center for Glaciology and a Fellow of the Cooperative 33 I new introductory chapter on the evolution and scope Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences.