The Rise and Fall of Crime in Abbotsford British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Vancouver Regional District

Greater Vancouver Regional District The Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) is a partnership of 21 municipalities and one electoral area that make up the metropolitan area of Greater Vancouver.* The first meeting of the GVRD's Board of Directors was held July 12, 1967, at a time when there were 950,000 people living in the Lower Mainland. Today, that number has doubled to more than two million residents, and is expected to grow to 2.7 million by 2021. GVRD's role in the Lower Mainland Amidst this growth, the GVRD's role is to: • deliver essential utility services like drinking water, sewage treatment, recycling and garbage disposal that are most economical and effective to provide on a regional basis • protect and enhance the quality of life in our region by managing and planning growth and development, as well as protecting air quality and green spaces. GVRD structure Because the GVRD serves as a collective voice and a decision-making body on a variety of issues, the system is structured so that each member municipality has a say in how the GVRD is run. The GVRD's Board of directors is comprised of mayors and councillors from the member municipalities, on a Representation by Population basis. GVRD departments are composed of staff and managers who are joined by a shared vision and common goals. Other GVRD entities Under the umbrella of the GVRD, there are four separate legal entities: the Greater Vancouver Water District (GVWD); the Greater Vancouver Sewerage and Drainage District (GVS&DD); the Greater Vancouver Housing Corporation (GVHC), and the Greater Vancouver Regional District. -

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area A collaboration in support of teachers in and around Abbotsford, B.C. in celebration of National Science and Technology Week October 25, 2013 MineralsEd and Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada Led by David Huntley, PhD, GSC and David Thompson, P Geo 1 2 Fraser Valley Geotour Introduction Welcome to the Fraser Valley Geotour! Learning about our Earth, geological processes and features, and the relevance of it all to our lives is really best addressed outside of a classroom. Our entire province is the laboratory for geological studies. The landscape and rocks in the Fraser Valley record many natural Earth processes and reveal a large part of the geologic history of this part of BC – a unique part of the Canadian Cordillera. This professional development field trip for teachers looks at a selection of the bedrock and overlying surficial sediments in the Abbotsford area that evidence these geologic processes over time. The stops highlight key features that are part of the geological story - demonstrating surface processes, recording rock – forming processes, revealing the tectonic history, and evidence of glaciation. The important interplay of these phenomena and later human activity is highlighted along the way. It is designed to build your understanding of Earth Science and its relevance to our lives to support your teaching related topics in your classroom. Acknowledgments We would like to thank our partners, the individuals who led the tour to share their expertise, build interest in the natural history of the area, and inspire your teaching. -

Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford

AFFORDABLE HOUSING Choices For Families Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford The Housing Listings is a resource directory of affordable housing in British Columbia and divides the Lower Mainland into 7 zones. Zone 7 identifies affordable housing in the Fraser Valley, Abbotsford and Chilliwack. The attached listings are divided into two sections. Section #1: Apply to The Housing Registry Section 1 - Lists developments that The Housing Registry accepts applications for. These developments are either managed by BC Housing, Non-Profit societies or Co- operatives. To apply for these developments, please complete an application form which is available from any BC Housing office, or download the form from www.bchousing.org/housing- assistance/rental-housing/subsidized-housing. Section #2: Apply directly to Non-Profit Societies and Housing Co-ops Section 2 - Lists developments managed by non-profit societies or co-operatives which maintain and fill vacancies from their own applicant lists. To apply for these developments, please contact the society or co-op using the information provided under "To Apply". Please note, some non-profits and co-ops close their applicant list if they reach a maximum number of applicants. In order to increase your chances of obtaining housing it is recommended that you apply for several locations at once. Family Housing, Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford August 2021 AFFORDABLE HOUSING SectionSection 1:1: ApplyApply toto TheThe HousingHousing RegistryRegistry forfor developmentsdevelopments inin thisthis section.section. Apply by calling 604-433-2218 or, from outside the Lower Mainland, 1-800-257-7756. You are also welcome to contact The Housing Registry by mail or in person at 101-4555 Kingsway, Burnaby, BC, V5H 4V8. -

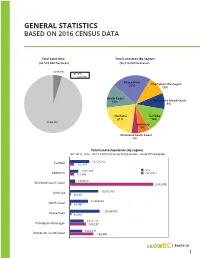

General Statistics Based on 2016 Census Data

GENERAL STATISTICS BASED ON 2016 CENSUS DATA Total Land Area Total Land Area (by region) (92,518,600 hectares) (92,518,600 hectares) 4,615,910 ALR non-ALR Peace River 22% Thompson-Okanagan 10% North Coast 13% Vancouver Island-Coast 9% Nechako Cariboo 21% 14% 87,902,700 Kootenay 6% Mainland-South Coast 4% Total Land & Population (by region) (BC total - Area - 92,518,600 (hectares) & Population - 4,648,055 (people)) Cariboo 13,128,585 156,494 5,772,130 Area Kootenay Population 151,403 3,630,331 Mainland-South Coast 2,832,000 19,202,453 Nechako 38,636 12,424,002 North Coast 55,500 20,249,862 Peace River 68,335 9,419,776 Thompson-Okanagan 546,287 8,423,161 Vancouver Island-Coast 799,400 GROW | bcaitc.ca 1 Total Land in ALR (etare by region) Total Nuber o ar (BC inal Report Number - 4,615,909 hectares) (BC total - 17,528) Cariboo 1,327,423 Cariboo 1,411 Kootenay 381,551 Kootenay 1,157 Mainland-South Coast 161,961 Mainland-South Coast 5,217 Nechako 747 Nechako 373,544 North Coast 116 North Coast 109,187 Peace River 1,335 Peace River 1,333,209 Thompson-Okanagan 4,759 Thompson-Okanagan 808,838 Vancouver Island-Coast 2,786 Vancouver Island-Coast 120,082 As the ALR has inclusions and exclusions throughout the year the total of the regional hectares does not equal the BC total as they were extracted from the ALC database at different times. Total Area o ar (etare) Total Gro ar Reeipt (illion) (BC total - 6,400,549) (BC total - 3,7294) Cariboo 1,160,536 Cariboo 1063 Kootenay 314,142 Kootenay 909 Mainland-South Coast 265,367 Mainland-South Coast 2,4352 -

British Columbia Coast Birdwatch the Newsletter of the BC Coastal Waterbird and Beached Bird Surveys

British Columbia Coast BirdWatch The Newsletter of the BC Coastal Waterbird and Beached Bird Surveys Volume 6 • November 2013 COASTAL WATERBIRD DATA SUPPORTS THE IMPORTANT BIRD AREA NETWORK by Krista Englund and Karen Barry Approximately 60% of British Columbia’s BCCWS data was also recently used to 84 Important Bird Areas (IBA) are located update the English Bay-Burrard Inlet and along the coast. Not surprisingly, many Fraser River Estuary IBA site summaries. BC Coastal Waterbird Survey (BCCWS) Both sites have extensive coastline areas, IN THIS ISSUE sites are located within IBAs. Through the with approximately 40 individual BCCWS • Coastal Waterbird survey, citizen scientists are contributing sites in English Bay Burrard Inlet and 22 Survey Results valuable data to help refine boundaries of in the Fraser River Estuary, although not • Beached Bird IBAs, update online site summaries (www. all sites are surveyed regularly. BCCWS Survey Results ibacanada.ca), and demonstrate that data helped demonstrate the importance • Common Loons these areas continue to support globally of English Bay-Burrard Inlet to Surf • Triangle Island significant numbers of birds. Scoters and Barrow’s Goldeneyes. In the • Forage Fish Fraser River Estuary, BCCWS data was • Tsunami Debris One recent update involved amalgamating particularly useful for demonstrating use • Real Estate three Important Bird Areas near Comox on of this IBA by globally significant numbers Foundation Project Vancouver Island into a single IBA called of Thayer’s Gull, Red-necked Grebe and • Web Resources K’omoks. BCCWS data from up to 52 survey Western Grebe. sites on Vancouver Island, Hornby and Denman Islands helped to identify areas BCCWS surveyors have made great of high bird use and provide rationale contributions to the BC Important Bird for the new boundary, which extends Areas program and we thank all past and from approximately Kitty Coleman Beach present volunteers. -

Agricultural Economy in the Fraser Valley Regional District TABLE of CONTENTS

Image courtesy Chilliwack Economic Partners Corp Regional Snapshot Series: Agriculture Agricultural Economy in the Fraser Valley Regional District TABLE OF CONTENTS A Region Defined by Agriculture Competitive Advantage Economics of Agriculture: A National Perspective Economics of Agriculture: Provincial Context Economics of Agriculture: Regional Context Agricultural Land Reserve Agricultural Diversity Agriculture Challenges Agriculture Opportunities Regional Food Security The Fraser Valley Regional District is comprised of 6 member municipalities and 7 electoral areas. City of Abbotsford, City of Chilliwack, District of Mission, District of Hope, District of Kent, Village of Harrison Hot Springs and Electoral Areas A, B, C, D, E, F and G. Fraser Valley Regional District In partnership with: A NOTE ON CENSUS DATA LIMITATIONS Although every effort has been made in the preparation of the Regional Snapshot Series to present the most up-to-date information, the most recent available Census data is from 2006. The most recent Census of Agriculture took place in May of 2011, however results will not be available until mid-2012. The snapshot will be updated to reflect the 2011 Census of Agriculture results. A REGION DEFINED BY AGRICULTURE CHOICES FOR TODAY AND INTO THE FUTURE OUR FUTURE: Agriculture: A 21st century industry The Fraser Valley Regional District (FVRD) is comprised of six member municipalities our Regional and seven electoral areas and features a variety of diverse communities, from small rural hamlets to the fifth largest city in British Columbia. The FVRD is one of the most Growth Strategy intensively farmed areas in Canada, generating the largest annual farm receipts of any regional district in British Columbia. -

Freestanding Building with Exceptional Exposure Onto Highway 1

1555United Boulevard Coquitlam, BC FOR SALE FEATURED BENEFITS Zoning: B-1 Business Enterprise Freestanding Building with Exceptional Exposure onto Unparalleled access to highways and Highway 1 amenities Asking Price: 10,500,000 1555 UNITED BOULEVARD, COQUITLAM // FOR SALE The Opportunity OPPORTUNITY To acquire a retail/industrial property with over 153’ of frontage along United FAVOURABLE COMMERCIAL Boulevard and in the heart of the Lower Mainland’s furniture, appliance and ZONING home improvement retail node. The property offers holding income and long-term B-1 - Business Enterprise Zone redevelopment to take advantage of the master planned Fraser Mills development that will see 4,700 new homes and very easy access to Trans Canada and Lougheed The City of Coquitlam’s B-1 zone provides for most types Highways. of retail uses, office uses, commercial recreation uses and commercial uses which support industrial activities. HIGHLIGHTS Redevelopment: • 1 acre gross site with over 153 feet of United Boulevard frontage and direct exposure to Highway 1 The B-1 zone allows for a density of 2.0 FSR with a maximum height of 8-storeys. • Flexible B-1 “Business Enterprise” zoning allowing for retail, industrial, office and recreational uses • Centrally located and easily accessible destination retail node with a population of over 1,800,000 within a 30 minute drive • Easy access/egress to the site • Well maintained building currently improved with a home furnishings showroom • 15,015 SF on the main floor of building with a 13,195 SF mezzanine comprised -

Flood Mitigation Planning in BC's Lower Mainland

Flood Mitigation Planning in BC’s Lower Mainland Steve Litke, Senior Program Manager Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction | April 20, 2018 Lower Mainland Flood Management Strategy Presentation Outline: 1. Intro to Fraser Basin and Fraser Basin Council 2. Context – the region & regional flood hazards 3. Regional Flood Strategy – Who, What, Where, When, Why and How? 4. Phase 1 Results 5. Phase 2 – Key Components & Activities 6. The Environment and Climate Change 7. Recap and Outstanding Issues 1. Introduction to the Fraser River and Fraser Basin Council Fraser Basin Council • Fraser River flows ~1400 km from Mt Robson to Vancouver • Area is about 220,000 km2 • Nongovernmental organization with a mandate to advance sustainability • 38-member Board of Directors comprised of the four orders of government, private sector and civil society interests • Impartial role as convener of inclusive and constructive dialogue • Role to assist in resolution of complex, inter-jurisdictional sustainability issues (e.g. flood hazard management) • Three priority areas: 1. Climate Change and Air Quality 2. Healthy Watersheds and Water Resources 3. Sustainable Communities and Regions 2. Context Recent History Lead-up to the regional strategy – a chronology: • Joint Program Committee established in 1998 • Numerous technical projects, practitioners’ network, forum for dialogue & exchange • 2006 Lower Fraser Hydraulic Model and new design flood profile • 2007 freshet • SLR studies and 2012 Cost of Adaptation report • 2013 consultation and business plan • 2013 Alberta and Ontario floods • Several coastal flood events in BC • Support and funding for a regional strategy BC’s Lower Mainland Squamish Fraser River freshet (spring flood) Hope Richmond Coastal storm surge (winter flood) White Rock White Rock Lower Mainland Flood Hazards • Fraser River flood (spring) • Large snowpack (esp. -

Oceanography of the British Columbia Coast

CANADIAN SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF FISHERIES AND AQUATIC SCIENCES 56 DFO - L bra y / MPO B bliothèque Oceanography RI II I 111 II I I II 12038889 of the British Columbia Coast Cover photograph West Coast Moresby Island by Dr. Pat McLaren, Pacific Geoscience Centre, Sidney, B.C. CANADIAN SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF FISHERIES AND AQUATIC SCIENCES 56 Oceanography of the British Columbia Coast RICHARD E. THOMSON Department of Fisheries and Oceans Ocean Physics Division Institute of Ocean Sciences Sidney, British Columbia DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND OCEANS Ottawa 1981 ©Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1981 Available from authorized bookstore agents and other bookstores, or you may send your prepaid order to the Canadian Government Publishing Centre Supply and Service Canada, Hull, Que. K1A 0S9 Make cheques or money orders payable in Canadian funds to the Receiver General for Canada A deposit copy of this publication is also available for reference in public librairies across Canada Canada: $19.95 Catalog No. FS41-31/56E ISBN 0-660-10978-6 Other countries:$23.95 ISSN 0706-6481 Prices subject to change without notice Printed in Canada Thorn Press Ltd. Correct citation for this publication: THOMSON, R. E. 1981. Oceanography of the British Columbia coast. Can. Spec. Publ. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56: 291 p. for Justine and Karen Contents FOREWORD BACKGROUND INFORMATION Introduction Acknowledgments xi Abstract/Résumé xii PART I HISTORY AND NATURE OF THE COAST Chapter 5. Upwelling: Bringing Cold Water to the Surface Chapter 1. Historical Setting Causes of Upwelling 79 Origin of the Oceans 1 Localized Effects 82 Drifting Continents 2 Climate 83 Evolution of the Coast 6 Fishing Grounds 83 Early Exploration 9 El Nifio 83 Chapter 2. -

The High-Wind Climatology of Vancouver and Abbotsford

The High-Wind Climatology of Vancouver and Abbotsford A Exploration of Contrasts Over a Small Spatial Scale, and Some Possible Regional Trends in Windstorm Frequency Wolf Read MSc Candidate in Forest Science University of British Columbia Overview Lower Mainland, BC, High-Wind Storms • Annual Frequency of windstorms at Vancouver and Abbotsford and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) • Westerly windstorms at Vancouver compared to Abbotsford • Trends in Fraser River Valley outflow events (“Arctic outbreaks”) Definitions • Minimum High-Wind Criteria Storm: • 64 km/h (35-knot) 1-min wind* • 93 km/h (50-knot) 1-sec to 3-sec gust • Minimum Catastrophic High-Wind Storm: • 80 km/h (43-knot) 1-min wind • 113 km/h (61-knot) 1-sec to 3-sec gust • To be high-wind criteria, either wind or gust must meet the minimum value. Both are not required. * 63 km/h wind included due to conversion factors: 34-kt = 39.10 mph = 63 km/h 35-kt = 40.15 mph = 65 km/h Methods • Wind speed and direction data from Environment Canada, obtained from “Climate Data Online”. • Observation period: Jan 1955 - Jan 2008. • This sorting filter applied: • All events with a 74 km/h or higher peak gust noted • Interesting events with 69 - 73 km/h peak included • Filter likely captures: • All events with a 93 km/h or higher peak gust • Most events with 63 km/h or higher 1-minute wind • All Fraser outflow events with 74 km/h or higher gust Annual Frequency of High Wind Events at Vancouver International Airport Influenced by the Pacific Decadal Oscillation? Timing of recent PDO cold-phase -

30686 Matsqui Place

FOR SALE ABBOTSFORD MULTI-TENANT INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX FACING HIGHWAY 1 TRANS-CANADA HWY HIGHSTREET SHOPPING CENTRE MT LEHMAN RD 30686 MATSQUI PLACE ABBOTSFORD, BRITISH COLUMBIA KYLE DODMAN CHRIS MACCAULEY PERSONAL REAL ESTATE CORPORATION PERSONAL REAL ESTATE CORPORATION 604.309.9446 | [email protected] 604.662.5190 | [email protected] THE THE OPPORTUNITY LOCATION CBRE Limited is pleased to present the opportunity to acquire a multi-tenant industrial complex This property is strategically located in Abbotsford’s Peardonville Industrial area and boasts excellent with Trans-Canada Highway exposure in the Mt Lehman Industrial area. The complex consist of access and exposure to Highway 1. It is centrally located within a 5 minute drive of the Mount Lehman approximately 27,434 SF over two buildings situated on 1.58 acres of land. Road - Highway 1 interchange, the Clearbrook Road - Highway 1 interchange, and the Abbotsford International Airport. Additionally, the Sumas border crossing is conveniently located 20 minutes The Subject property has varying lease expiries in the coming 12-24 months which creates a great south-east. opportunity for an industrial business to occupy the complex or an investor to acquire it to add-value long term. The site is zoned and designated I-2 General industrial which allows a wide range of industrial The surrounding area is a growing industrial hub with a variety of national and local businesses. The uses including outside storage area is experiencing significant growth with new development occurring surrounding the Abbotsford International Airport as well as infrastructure improvements, including the widening of Mt. Lehman Road and the Marshall Road alignment connecting Marshall Road to 16th avenue and the rest of the Fraser Valley. -

THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE of the LOWER FRASER RIVER July 2014

THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE LOWER FRASER RIVER July 2014 Prepared by the Richmond Chamber of Commerce with the assistance of D.E. Park & Associates Ltd. and with the support of: Richmond Chamber of Commerce Burnaby Board of Trade Maple Ridge & Pitt Meadows Chamber of Commerce Surrey Board of Trade Greater Langley Chamber of Commerce Chilliwack Chamber of Commerce The Vancouver Board of Trade Delta Chamber of Commerce Hope & District Chamber of Commerce Tri-Cities Chamber of Commerce Mission Regional Chamber of Commerce Province of British Columbia, Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure Abbotsford Chamber of Commerce New Westminster Chamber of Commerce THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF THE LOWER FRASER RIVER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Recognition goes to those organizations that funded this endeavour: • Richmond Chamber of Commerce • Surrey Board of Trade • Vancouver Board of Trade • Tri-Cities Chamber of Commerce • Abbotsford Chamber of Commerce • Burnaby Board of Trade • Greater Langley Chamber of Commerce • Delta Chamber of Commerce • Mission Regional Chamber of Commerce • New Westminster Chamber of Commerce • Maple Ridge and Pitt Meadows Chamber of Commerce • Province of British Columbia, Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure Special thanks go to the report’s principal researcher and co-author, Dave Park, of D.E. Park & Associates Ltd., and to co-author Matt Pitcairn, Manager of Policy and Communications at the Richmond Chamber of Commerce, who provided extensive support in data gathering, stakeholder engagement, document preparation and drafting report sections. The experience and detailed knowledge of Allen Domaas, retired CEO of the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, has also added significantly to this report. A number of organizations and knowledgeable individuals were consulted and generously provided input and perspective to this work.