Why Abortion? Entire Booklet Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undue Burden Beyond Texas: an Analysis of Abortion Clinic Closures, Births, and Abortions in Wisconsin

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES UNDUE BURDEN BEYOND TEXAS: AN ANALYSIS OF ABORTION CLINIC CLOSURES, BIRTHS, AND ABORTIONS IN WISCONSIN Joanna Venator Jason Fletcher Working Paper 26362 http://www.nber.org/papers/w26362 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2019 Thanks to Jenny Higgins, Heather Royer, and Scott Cunningham for useful comments on the paper. Thanks to Lily Schultze and Jessica Polos for generous research support in collection of abortion data and timing of policy changes in Wisconsin and to Caitlin Myers for discussions of data collection practices. This study was funded by a grant from a private foundation and by the Herb Kohl Public Service Research Competition. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2019 by Joanna Venator and Jason Fletcher. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Undue Burden Beyond Texas: An Analysis of Abortion Clinic Closures, Births, And Abortions in Wisconsin Joanna Venator and Jason Fletcher NBER Working Paper No. 26362 October 2019 JEL No. I1,I28,J13,J18 ABSTRACT In this paper, we estimate the impacts of abortion clinic closures on access to clinics in terms of distance and congestion, abortion rates, and birth rates. -

The Emerging Use of a Balancing Approach in Casey's Undue Burden

THE EMERGING USE OF A BALANCING APPROACH IN CASEY’S UNDUE BURDEN ANALYSIS Karen A. Jordan* ABSTRACT This Article highlights an important shift occurring in the analytical framework used to assess the constitutional validity of abortion related laws. Specifically, the Article analyzes the adoption by lower courts of a significant modification to the undue burden analysis developed by Justice O’Connor in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. As described by Justice O’Connor, the undue burden analysis focuses on the purpose or legislative basis of an abortion related law, and the effect of the law. If the law is reasonably related to a legitimate state interest, it should be upheld unless the effect of the law presents a substantial obstacle to a woman’s liberty interest in being able to legally decide to have an abortion before viability. Lower courts have recently introduced a balancing inquiry into the Casey analysis, at least as to an abortion related law enacted to serve state interests in health and safety, e.g., laws designed to prevent the potential for substandard care in the context of abortion. The balancing affects both steps of the Casey analysis. In assessing the legislative basis for the law, courts are requiring empirical proof that the law furthers state interests, and also are assessing the extent to which the interests are likely to be advanced. In assessing the effect of the law, a finding that the state has not produced sufficient empirical evidence showing a strong relationship between the law and state interests triggers a diminution of the concept of substantial obstacle. -

Disinformation, and Influence Campaigns on Twitter 'Fake News'

Disinformation, ‘Fake News’ and Influence Campaigns on Twitter OCTOBER 2018 Matthew Hindman Vlad Barash George Washington University Graphika Contents Executive Summary . 3 Introduction . 7 A Problem Both Old and New . 9 Defining Fake News Outlets . 13 Bots, Trolls and ‘Cyborgs’ on Twitter . 16 Map Methodology . 19 Election Data and Maps . 22 Election Core Map Election Periphery Map Postelection Map Fake Accounts From Russia’s Most Prominent Troll Farm . 33 Disinformation Campaigns on Twitter: Chronotopes . 34 #NoDAPL #WikiLeaks #SpiritCooking #SyriaHoax #SethRich Conclusion . 43 Bibliography . 45 Notes . 55 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study is one of the largest analyses to date on how fake news spread on Twitter both during and after the 2016 election campaign. Using tools and mapping methods from Graphika, a social media intelligence firm, we study more than 10 million tweets from 700,000 Twitter accounts that linked to more than 600 fake and conspiracy news outlets. Crucially, we study fake and con- spiracy news both before and after the election, allowing us to measure how the fake news ecosystem has evolved since November 2016. Much fake news and disinformation is still being spread on Twitter. Consistent with other research, we find more than 6.6 million tweets linking to fake and conspiracy news publishers in the month before the 2016 election. Yet disinformation continues to be a substantial problem postelection, with 4.0 million tweets linking to fake and conspiracy news publishers found in a 30-day period from mid-March to mid-April 2017. Contrary to claims that fake news is a game of “whack-a-mole,” more than 80 percent of the disinformation accounts in our election maps are still active as this report goes to press. -

Shameless Sociology

Shameless Sociology Shameless Sociology: Critical Perspectives on a Popular Television Series Edited by Jennifer Beggs Weber and Pamela M. Hunt Shameless Sociology: Critical Perspectives on a Popular Television Series Edited by Jennifer Beggs Weber and Pamela M. Hunt This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Jennifer Beggs Weber, Pamela M. Hunt and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5744-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5744-4 For Nathan, my partner in crime. – Jennifer For Perry and Grace. – Pam TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Pamela M. Hunt and Jennifer Beggs Weber Part 1: Social Class Dominant Hasslin’ and Subordinate Hustlin’: A Content Analysis Using the Generic Processes that Reproduce Inequality ............................ 8 Alexis P. Hilling, Erin Andro, and Kayla Cagwin Shamefully Shameless: Critical Theory and Contemporary Television ... 29 Robert J. Leonard and Kyra -

Shameless Television: Gendering Transnational Narratives

This is a repository copy of Shameless television: gendering transnational narratives. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/129509/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Johnson, B orcid.org/0000-0001-7808-568X and Minor, L (2019) Shameless television: gendering transnational narratives. Feminist Media Studies, 19 (3). pp. 364-379. ISSN 1468-0777 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1468795 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Shameless Television: Gendering Transnational Narratives Beth Johnson ([email protected]) and Laura Minor ([email protected]) School of Media and Communication, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK Abstract The UK television drama Shameless (Channel 4, 2004-2011) ran for eleven series, ending with its 138th episode in 2011. The closing episode did not only mark an end, however, but also a beginning - of a US remake on Showtime (2011-). Eight series down the line and carrying the weight of critical acclaim, this article works to consider the textual representations and formal constructions of gender through the process of adaptation. -

Playing with Fire: an Ethnographic Look at How Polyamory Functions in the Central Florida Burner Community

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2015 Playing with Fire: An Ethnographic Look at How Polyamory Functions in the Central Florida Burner Community Maleia Mikesell University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mikesell, Maleia, "Playing with Fire: An Ethnographic Look at How Polyamory Functions in the Central Florida Burner Community" (2015). HIM 1990-2015. 613. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/613 PLAYING WITH FIRE: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC LOOK AT HOW POLYAMORY FUNCTIONS IN THE CENTRAL FLORIDA BURNER COMMUNITY by MALEIA MIKESELL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Honors in the Major Program in Anthropology In the College of Sciences and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2015 Thesis Chair: Dr. Beatriz Reyes-Foster Abstract This thesis asks the question as to whether polyamory functions as a community glue or solvent for the Central Florida Burner Community. It explores the definition of polyamory and how it relates to the Burner counter-culture. This thesis explores what polyamory’s effects are on the individual and community levels for those who participate in it. The findings concluded that overall the participants reported a perceived positive impact on both the individual level and on community cohesion in this case. -

STUART JOHNSON Electrician/Film&TV Lighting Gaffer

STUART JOHNSON Electrician/Film&TV Lighting Gaffer 07708720366 [email protected] Imdb Stuart Johnson XIII J I B Registered electrician City and Guilds Electrical Installation Part I 1996 & Part II 1997 AM1 & AM2 1998. Vocational Qualification 050(NVQ) 1998. Royal Air Force City and Guilds Electrical/Electronics Competences 2001. 17th Edition IEE Wiring Regs. Full driving licence, HGV Class 2. Ipaf cherry picker licence. 2018 James Arthur & Anne Marie (music vid) Gaffer, Dop Sam Meyer. https://youtu.be/pRfmrE0ToTo Little Joe (Feature Film) Best boy, Gaffer Werner Stibitz. Bureau Films Ltd. The Valley of the Fox (German TV Film) Best boy, Gaffer Roland Schnitter. UFA Fiction Germany. Paul Pogba World Cup interview (Fox USA) Gaffer. Dop Adam Docker, Red Earth Studio. Cancer Awareness (Commercial) Gaffer. Dop Adam Gillham, MTP Ltd. Man City (Spirable promo) Gaffer. The Mob Films. Jessica Hennis-Hill Adidas (Promo) Gaffer. WeAreSocial Ltd. Tadashi Izumi (Japanese promo vid) Gaffer. Turn Productions Ltd. Uber with Mo Salah (Commercial) Rigging Gaffer. WigWam Films. https://youtu.be/-u4jqI4J_yg Angry birds @ Everton FC with Wayne Rooney (Promo) Lighting Tech. The Mob Films. Adidas The Answer (Commercial) Lighting Tech. Iconoclast TV. Gucci (Commercial) Lighting Tech. North Six Europe Ltd. Aleixis Sanchez Man U (Signing promo) Lighting Tech. The Mob Films. Moving on 10 (TV Drama) Lighting Tech. Dop Len Gowing. LA Productions. 2017 The Zoo (Feature Film) Gaffer. DOP Damien Elliott. Northern Ireland, Wee Bun films. https://youtu.be/TSNMPCG8m5M The Souvenir Pt1 (Feature Film). Gaffer. DOP David Raedekker. Cheated (German Feature Film) Best Boy. Gaffer Roland Schnitter. UFA Fiction Germany. Moving on 9 (TV Drama) Best Boy. -

The Abortion Controversy: the Law's Response

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 48 Issue 2 Article 5 October 1971 The Abortion Controversy: The Law's Response Lyle B. Haskin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lyle B. Haskin, The Abortion Controversy: The Law's Response, 48 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 191 (1971). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol48/iss2/5 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. NOTES AND COMMENTS THE ABORTION CONTROVERSY: THE LAW'S RESPONSE I. INTRODUCTION Abortion laws appear to provide a classic example of the law's role in fol- lowing social trends, rather than in leading social advancements. The law has changed from providing for no punishment where a pregnancy is intentionally aborted before "quickening," 1 to charging a felony for inducing abortion, cer- tain exceptions notwithstanding. As a result, the law stands today in a vulner- able position. When courts strike down anti-abortion statutes, a certain segment of the population sees the result as a further decline of traditional morality. When, on the other hand, courts find such statutes constitutional, they are met with a barrage of criticism from those favoring liberalized abortion statutes. The main criticism is that archaic ideas permeate the law and are inflexibly followed de- spite changed social requirements. -

A Guide to Shameless Happiness Ebook Free Download

A GUIDE TO SHAMELESS HAPPINESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Will Ross | 42 pages | 18 Jun 2014 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781499769241 | English | United States A Guide to Shameless Happiness PDF Book Sign in to play Series 1 Episode 1. Over the past couple of seasons, we've seen each of these kids grow into their own and move in their own direction. I just think that it's each one of their individual stories, the narratives going on for each one of them. I absolutely loved what you did with Ian in Cameron Monaghan's final episode , but it did bring up this question of, is it possible for anyone on the show to have a true happy ending or is there always a Shameless twist? S9 E2 Recap. When the family finds Frank started a homeless shelter, Frank turns all but Liam away since they are now against him. Recommendations Discover Listings News. He catches Karen giving oral sex to Ian and becomes enraged. She later tells Frank that she is dying and that she returned in order to leave something behind for the children. He is a heroin addict who struggles to kick the habit. In season 7, he learns that Dominique cheated on him when he tests negative for an STD she contracted, causing the two to break up. Chuckie is presumed to be taken care of by his grandmother when Frank and Debbie leave the commune. Lip's new girlfriend Amanda helps him and his grades improve. Toward the end of the season, she begins seeing a dashing Irish man named Ford. -

Planned Parenthood Federation Of

No. 15-274 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- WHOLE WOMAN’S HEALTH; AUSTIN WOMEN’S HEALTH CENTER; KILLEEN WOMEN’S HEALTH CENTER; NOVA HEALTH SYSTEMS D/B/A REPRODUCTIVE SERVICES; SHERWOOD C. LYNN, JR., M.D.; PAMELA J. RICHTER, D.O.; and LENDOL L. DAVIS, M.D., on behalf of themselves and their patients, Petitioners, v. KIRK COLE, M.D., Commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services; and MARI ROBINSON, Executive Director of the Texas Medical Board, in their official capacities, Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE PLANNED PARENTHOOD FEDERATION OF AMERICA, PLANNED PARENTHOOD OF GREATER TEXAS SURGICAL HEALTH SERVICES, PLANNED PARENTHOOD CENTER FOR CHOICE, AND PLANNED PARENTHOOD SOUTH TEXAS SURGICAL CENTER IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- --------------------------------- CARRIE Y. F LAXMAN Counsel of Record HELENE T. KRASNOFF PLANNED PARENTHOOD FEDERATION OF AMERICA 1110 Vermont Avenue, NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 973-4800 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS -

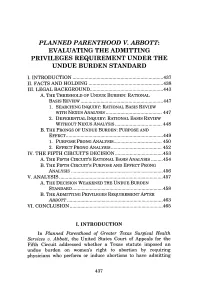

Planned Parenthood V. Abbott: Evaluating the Admitting Privileges Requirement Under the Undue Burden Standard

PLANNED PARENTHOOD V. ABBOTT: EVALUATING THE ADMITTING PRIVILEGES REQUIREMENT UNDER THE UNDUE BURDEN STANDARD I. IN TRO D U CTIO N .................................................................... 437 II. FACTS AND HOLDING ........................................................ 438 III. LEGAL BACKGROUND ....................................................... 443 A. THE THRESHOLD OF UNDUE BURDEN: RATIONAL BASIS R EVIEW .............................................................. 447 1. SEARCHING INQUIRY: RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW WITH NEXUS ANALYSIS .......................................... 447 2. DEFERENTIAL INQUIRY: RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW WITHOUT NEXUS ANALYSIS ................................... 448 B. THE PRONGS OF UNDUE BURDEN: PURPOSE AND E FFE CT ......................................................................... 449 1. PURPOSE PRONG ANALYSIS .................................... 450 2. EFFECT PRONG ANALYSIS ...................................... 452 -V. THE FIFTH CIRCUIT'S DECISION .................................... 453 A. THE FIFTH CIRCUIT'S RATIONAL BASIS ANALYSIS ......... 454 B. THE FIFTH CIRCUIT'S PURPOSE AND EFFECT PRONG A NALYSIS ..................................................................... 456 V . A N ALY SIS .............................................................................. 457 A. THE DECISION WEAKENED THE UNDUE BURDEN STAN DARD .................................................................... 458 B. THE ADMITTING PRIVILEGES REQUIREMENT AFTER A BBO TT ....................................................................... -

Emma Burge Producer

Emma Burge Producer Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes WOLFE Abbottvision / Sky Showrun by Paul Abbott. 2020 6x1 hour series TORVILL AND DEAN Endemol Shine UK / ITV Written by William Ivory, 1 x 2 2018 hour special CLEAN BREAK Octagon/RTE/152 Productions 2 Series 8 x 52 mins Written by Billy Roche Directed by Gillies Mackinnon and Damien O'Donnell THE VILLAGE Company Television Ltd / BBC1 6x1 hour series 2013 Written by Peter Moffat Starring John Simm and Maxine Peake SHAMELESS 12 Company Television Ltd Story lining with Shameless 2012 creator Paul Abbott TIN TOWN Company Television Ltd Series in development 2012 Co-created with Pete Jordi Wood and Tom Bidwell United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes Development Producer Touchpaper Television Development of television drama 2012 ideas Channel 4 COMING UP IWC / Channel 4 7 x 30’ films 2011 As executive producer COMING UP IWC / Channel 4 7 x 30’ films 2010 Written and directed by emerging UK talent TEN SPOT Company Television Ltd Series format 2009 OTHER PEOPLE Company Television Ltd / 30’ comedy pilot 2007 Channel 4 Written by Toby Whitehouse Starring Martin Freeman WHO GETS THE DOG? Company Television / ITV Single drama 2008 Written by Guy Hibbert, directed by Nick Renton Starring Kevin Whately, Alison Steadman SHAMELESS