Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a -

Stand-Up Comedy and Open Mike Nights

____________________________________________________________________ STAND-UP COMEDY AND OPEN MIKE NIGHTS By Steve North, the Comedy Coach _____________________________________________________________________ If you’re trying to get going in standup comedy, open mike nights can be the only early option. Navigating them and doing what works can be tricky, depressing, or sometimes exhilarating and a learning experience. But let’s start with a truth here. Stand up comedy is about the only skill that people jump up on stage to “give it a try” or to “learn.” If you were learning to play the piano, would you go to bars, jump up in front of audiences and start banging on the piano in front of them? Probably not. So first thing, get yourself trained somehow. Not all classes are good, and many teachers don’t know how to teach too well, but you’re still better off learning in a safer environment. Unfortunately, doing an open mike night can be like test driving a racing car on a rutted cracked unmarked race track – many techniques that work in an open mike night would bomb in a real comedy club environment. That said, many will go to open mikes anyway, so here are the goods, bads, and some tips: BAD. So many open mikers use blue words and material so often that the audience becomes de- sensitized, and it makes material that would normally work fine just seem like a boy- scout in a sex club. Women’s material seems to revolve around their vaginas and periods, and it’s hard to find an open miker male who doesn’t use his dick in almost every piece of comedy material. -

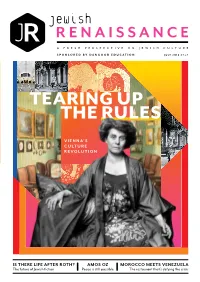

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

Laughing out Loud: Taking a Stand on Standup for the ESL Student Kathy Zimbaldi Westside High School INTRODUCTION I Am a Seconda

Laughing Out Loud: Taking a Stand on Standup for the ESL Student Kathy Zimbaldi Westside High School INTRODUCTION I am a secondary ESL teacher at Westside High School in HISD. I teach 10th, 11th, and 12th grade classes of Advanced and Transitional students, and my class populations are extremely diverse both culturally and linguistically. While many students are native Spanish speakers, most are from South America rather than Mexico. And while some of my Asian students are Chinese or Vietnamese, others are from Thailand, Bangladesh, or India. The native Arab speakers are from Iran, Lebanon, and Palestine, while the African ESL students are from Angola, Cameroon, or Nigeria. Unlike my previous ESL teaching experiences with 100% Mexican populations, my Westside High classroom is a mini-United Nations! While my own learning curve is steep as I seek to meet the needs of this very diverse group, I still try hard to maintain an atmosphere that keeps the affective filter low as my students struggle to learn in a second language. My goal is to promote a stress-free zone that encourages risk- taking; if we are to make steady progress toward language proficiency, then students must be comfortable manipulating that language. I choose to teach with a generous level of flexibility in the ESL curriculum, and I am fortunate to have the full support of my principal in this regard. Like Robin Williams’ students in Good Morning Vietnam or Bill Murray’s in Stripes, my students seem to appreciate any efforts I make to engage and entertain them as we tackle the more daunting lessons in English language learning. -

2016 Sydney Fringe Comedy Program

Sydney’s Best Value Comedy Show 10 COMEDIANS FOR $10 2016 PROGRAM A DIFFERENT LINE-UP OF COMEDIANS EVERY SHOW! ‘10 Comedians for $10’ Shows at 2016 Sydney Fringe Our 2016 Fringe Comedy Shows are at The Bat & Ball Hotel, 495 Cleveland St, Redfern. Click here to get tickets for our Sydney Fringe Comedy Shows. Click on a comedian’s name to view his/her profile. Click on links in right column to see other Fringe shows these comedians are performing. Sally Kimpton Sally Kimpton delights with stand-up that’s clever, edgy and hilarious! Sally has performed at the Melbourne International Comedy Festival in ‘Extreme Blonde’, followed by her one woman show ‘Sally Kimpton - MyStar’ at the Sydney Comedy Festival. She has appeared on and written material for national radio programmes, including on Triple J and Triple M. Sally’s TV appearances include The Comedy Channel’s ‘Headliners’ and ‘Stand-up Australia’. She was a quarter finalist in NBC’s ‘Last Comic Standing’ filmed at the Miami Improv in 2008. She has also been spotted on Network TEN’s ‘Thursday Night Live’ and Channel 7’s ‘Today Tonight’ (don’t ask!) In June 2012 Sally was invited to perform with Rove McManus and Wil Anderson in an Aussie comedy showcase in Los Angeles. Sally specialises as a Master of Ceremonies, Acts in Television and Film Productions and is finalising details for her first comedy book. A popular Headliner and a skilled MC, She has been making them laugh at fine, and not so fine comedy venues nationally and internationally for over 15 years! Website: sallykimpton.com Facebook: fb.com/The.Sally.Kimpton Youtube: youtube.com/sallykimpton 3 CJ Delling CJ is a comedian, cartoonist, podcaster and maker of stuff for the easily amused. -

Comedian Are Entertainers Who Make People Laugh by Using Variety Of

Comedian are entertainers who make people laugh by using variety of techniques to amuse the audience, such as telling jokes, singing humorous songs, doing impersonations and wearing funny costumes. Comedian performs in nightclubs, comedy clubs, theatres, television shows, films, and business functions. Comedians are performers responsible for entertaining people by making them laugh. Comedians have their own specific style, and may use various techniques like puppetry, ventriloquism, and music, to amuse audiences. Comedy is a form of art, and there are different types of comedy routines. When a performer uses a prop to make his/ her viewers laugh, it is known as a prop comedy. On the other hand, in stand-up comedy, the comedian is required to address the audience directly. Stand-up comedy is usually a one-man show where audience feedback plays a decisive role. Character comedy makes use of imaginary characters, while slapstick comedy pertains to the physical antics of the performer. Improvisational comedy can be the right pick for those with superb comic timing as these performances are mostly impromptu. Observational comedy refers to acts where mundane trivialities are exaggerated to make people laugh. Performers can concentrate their comic act on the aspect of word play. One can also choose to perform situational comedy which is now a popular genre on television. Television comedy mostly uses the “cringe” type of humor, where inappropriate actions and words are the source of laughter. Comedians are primarily responsible for writing comic material for their own performances, or for the web, radio, and print media. They need to rehearse their acts and be able to tailor them in accordance with the audiences’ preferences. -

Stand up Comedy and the Essay, Aka Louis C.K

Reinhart 1 EXPLORATIONS INTO STAND-UP COMEDY THROUGH THE MULTIMEDIA ESSAY: “STAND UP COMEDY AND THE ESSAY, AKA LOUIS C.K. MEET MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE” AND “YOU’RE IN THE SUN” A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Arts and Sciences in English By Taylor Reinhart April 2014 Reinhart 2 A. Introduction This thesis is an exploration of the tradition and practice of stand-up comedy. To accomplish this aim, I use the essay in both its traditional and non-traditional forms. My thesis consists of two pieces: “Stand Up Comedy And The Essay AKA Louis C.K. Meet Michel De Montaigne,” published in The Weeklings online magazine, and “You’re In The Sun,” a ten-minute video essay. These pieces each offer an analysis of comedy, but they also investigate the essay as a genre, focusing on the extent to which the video essay is an effective sub-genre for essayistic communication. My focus on the video essay is crucial to my critical introduction. To date, the video essay has a relatively short history as a subgenre and little critical commentary. After reviewing what little history and commentary exists, I offer my own definition and analysis of the video essay. I do so by first discussing the craft of the essay in general, especially as it pertains to stand-up comedy. I then place the video essay in that larger history, reviewing the critical discussion of this subgenre, referring to key video essay works, and showing the relevance of my enhanced definition and analysis. -

Comedy and Distinction: the Cultural Currency of a ‘Good’ Sense of Humour

Sam Friedman Comedy and distinction: the cultural currency of a ‘good’ sense of humour Book (Accepted Version) Original citation: Comedy and distinction: the cultural currency of a ‘good’ sense of humour, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2014, 228 pages. © 2017 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59932/ Available in LSE Research Online: September 2017 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Introduction: Funny to Whom? In January 2011, the scheduling plans of Britain’s biggest TV station, BBC 1, were leaked to the press. After the recent success of BBC comedies such as Outnumbered and My Family, BBC1 Controller Danny Cohen apparently told his team of producers that BBC Comedy was becoming ‘too middle class’, and failing in its responsibility to appeal to working class viewers (Gammell, 2011; Revoir, 2011; Leith, 2011). -

Behrooz Parhami

Behrooz Parhami Home & Contact Behrooz Parhami's Blog & Books Page Page last updated on 2015 December 31 Curriculum Vitae Research This page was created in March 2009 as an outgrowth of the section entitled "Books Read or Heard" in my personal page. The rapid expansion of the list of Computer arithmetic books warranted devoting a separate page to it. Given that the book introductions and reviews constituted a form of personal blog, I decided to title Parallel processing this page "Blog & Books," to also allow discussion of interesting topics Fault tolerance unrelated to books from time to time. Lately, non-book items (such as political Broader research news, tech news, puzzles, oddities, trivia, humor, art, and music) have formed the vast majority of the entries. Research history List of publications Entries in each section appear in reverse chronological order. Teaching Blog entries for 2015 Archived blogs for 2014 ECE1 Freshman sem Archived blogs for 2012-13 ECE154 Comp arch Archived blogs up to 2011 ECE252B Comp arith Blog Entries for 2015 ECE252C Adv dig des 2015/12/31 (Thursday): Here are five items of potential interest. ECE254B Par proc (1) Photographer Angela Pan's fantastic capture of the Vietnam veterans' ECE257A Fault toler memorial in Washington, DC. (2) Muslim sufis play traditional Christmas music. Student supervision (3) Media circus about Bill Cosby: I am so very glad that Bill Cosby has finally Math + Fun! been charged with sexual crimes. I am not glad at all that an ugly media frenzy and trial by pundits has already begun. It was okay to discuss the issue earlier Textbooks because years of accusations by dozens of women were not being taken seriously. -

LOST & FOUND COWBOY – Uplifting Cross-Cultural Online Comedy In

Special Article 7 LOST & FOUND COWBOY – Uplifting Cross-Cultural Online Comedy in the Time of Pandemic (Part 1) By Atsushi Ogata Author Atsushi Ogata COWBOY ® is a one-man sketch comedy series based on my own fish-out-of-water experiences of growing up and living in different countries. My observational comedy turns cultural shocks into laughter. With a cowboy hat, Japanese yukata (a casual, traditional summer garment) and rapid-fire patter, the character Yukata Cowboy drifts across the US, Japan, and Europe. He repeatedly stumbles across more than he bargains for; trying to fit in everywhere he goes. Each episode of YUKATA COWBOY ® is one to three minutes long (30 episodes in total) and takes the format of sketch comedy, focusing on an aspect of the everyday from the perspective of a man who travels his whole life between cultures: elevators, riding trains, bikes, travelling or making friends. In each country, Yukata Cowboy tries to learn the ropes and fit in, but the more he fits in, the more Our globetrotting romantic comedy web series LOST & FOUND COWBOY opens in Tokyo often he is mistaken for someone else. Amidst all his accommodation and travels the world on Twisted Mirror TV! © Globetrot Productions 2020 of perplexing newness, he struggles to find his own voice. I play Yukata Cowboy as well as all the other characters of different ages, gender and nationality. I filmed the series myself with an With the current global pandemic, our daily lives and routines have iPhone. Initially, I started this series as a therapy after my father’s become extremely disrupted and our activities restricted. -

Tell Us a Joke Challenge Instructions

“TELL US A JOKE” CHALLENGE Record a video of you telling three different kinds of jokes, focusing on delivery 1. Check out the “Anatomy of a Joke” and “Types of Jokes” information (below). This video does a great job explaining why there are many kinds of humor and what you can do to improve your joke-telling: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SmrC6W5IgCU 2. Write or find at least three jokes. Try to choose jokes that each fall into a different type of joke category so that you get practice with more than one kind of humor. Write your jokes on the page provided (below). If you’re interested in writing your own jokes, check out this video of Jerry Seinfeld: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=itWxXyCfW5s 3. Check out the “Tips on Delivery” information (below). Here’s a great video on that: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/jun/19/how-tell-jokes-like-pro-leah- green 4. Practice them out loud! First practice saying your joke out loud to yourself. When you feel comfortable, try delivering it to a family member or a recording device. Do a little self-analysis and see if there are delivery improvements to be made. 5. When you’re ready, record yourself. Keep in mind that it can be difficult to tell a joke to a camera without an audience reaction. You may want to film yourself telling a joke to a family member. If you do this, make sure you’re telling them the joke for the first time when you capture it on video. -

COMEDY in the LUDONARRATIVE 8 Comedic Video Games Is Presented

oskari o. kallio COMEDY IN THE LUDONARRATIVE defining a f r a m e w o r k for c ategorization of g a m e s f eaturing h umor t hrough t h e i r l udic and n arrative e lements Master’s Thesis Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture COMEDY IN THE LUDONARRATIVE Defining a Framework for Categorization of Games Featuring Humor Through Their Ludic and Narrative Elements Oskari O. Kallio, 2018 Master’s Thesis (Master of Arts) Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture Department of Media, Visual Communication Design TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 VI 88 Acknowledgements The Three Comical Conflicts 8 VI.I 89 Abstract The Inner Conflict Within a Comical Character 9 VI.I.I 91 Abstrakti Game Design as a Method of Disclosing the Inner Conflict 95 VI.II Interpersonal Conflict Between Two or More Characters 10 VI.II.I 97 I Introduction Stereotype Threat 11 VI.III 99 I.I Foreword Global Conflict Between a Character and a World 12 VI.III.I 101 I.II Thesis Statement & Research Question Absurd Worlds 13 I.III Contents and Objectives 14 VII 106 I.IV Methods of Research Case Studies 108 VII.I Grim Fandango 18 VII.I.I 110 II About Comedy And Humor What’s The Deal With The Dead ? 19 VII.I.II 116 II.I Logic on Leisure Deaths and Dead Ends 21 VII.I.III 119 II.II Video Game Medium as a Template for Comedic Narratives Converting Tragedy into Vigor 23 VII.II 122 II.II.I The Complexity of Ludonarrative Comedy Portal 2 28 VII.II.I 123 II.II.II The Visuality of Ludonarrative Comedy Comedy Is a Performance 126 VII.II.II The Thematic Framework