New Style in Sitcom Exploring Genre Terms of Contemporary American Comedy TV Series Through Their Utilization of Documentary Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

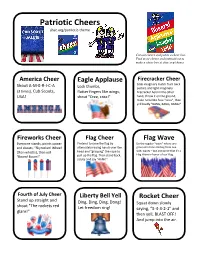

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

What Is Cosplay?

NO, REALLY: WHAT IS COSPLAY? Natasha Nesic A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a B. A. in Anthropology with Honors. Mount Holyoke College May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “In anthropology, you can study anything.” This is what happens when you tell that to an impressionable undergrad. “No, Really: What is Cosplay?” would not have been possible without the individuals of the cosplay community, who gave their time, hotel room space, and unforgettable voices to this project: Tina Lam, Mario Bueno, Rob Simmons, Margaret Huey, Chris Torrey, Chris Troy, Calico Singer, Maxiom Pie, Cassi Mayersohn, Renee Gloger, Tiffany Chang, as well as the countless other cosplayers at AnimeNEXT, Anime Expo, and Otakon during the summer of 2012. A heap of gratitude also goes to Amanda Gonzalez, William Gonzalez, Kimberly Lee, Patrick Belardo, Elizabeth Newswanger, and Clara Bertagnolli, for their enthusiasm for this project—as well as their gasoline. And to my parents, Beth Gersh-Nesic and Dusan Nesic, who probably didn’t envision this eight years ago, letting me trundle off to my first animé convention in a homemade ninja getup and a face full of Watercolor marker. Many thanks as well to the Mount Holyoke College Anthropology Department, and the Office of Academic Deans for their financial support. Finally, to my advisor and mentor, Professor Andrew Lass: Mnogo hvala za sve. 1 Table of Contents Introduction.......................................................................................................................................3 -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

17 Essential Social Skills Every Child Needs to Make & Retain Friends

Thriving Series by MICHAEL GROSE 17 essential social skills every child needs to make & retain friends www.parentingideas.com.au 17 essential social skills every child needs to make and retain friends Contents Skill 1: Ability to share possessions and space 4 Skill 2: Keeping confidences and secrets 4 Skill 3: Offering to help 5 Skill 4: Accepting other’s mistakes 5 Skill 5: Being positive and enthusiastic 6 Skill 6: Holding a conversation 6 Skill 7: Winning and losing well 7 Skill 8: Listening to others 7 Skill 9: Ignoring someone who is annoying you 8 Skill 10: Giving and receiving compliments 8 Skill 11: Approaching and joining a group 9 Skill 12: Leading rather than bossing 9 Skill 13: Arguing well – seeing other’s opinions 10 Skill 14: Bringing others into the group 10 Skill 15: Saying No – resisting peer pressure 11 Skill 16: Dealing with fights and disagreements 11 Skill 17: Being a good host 12 Get a ready-to-go At Home parenting program now at www.parentingideas.com.au 2 17 essential social skills every child needs to make and retain friends First a few thoughts Popularity should not be confused with sociability. A number of studies in recent decades have shown that appearance, personality type and ability impact on a child’s popularity at school. Good-looking, easy-going, talented kids usually win peer popularity polls but that doesn’t necessarily guarantee they will have friends. Those children and young people who develop strong friendships have a definite set of skills that help make them easy to like, easy to relate to and easy to play with. -

Marines Rescue Fishermen

HAWAII MARINE Voluntary payment for delivery to MCAS housing /$I per four week period. VOL. 11 NO. 24 KANEOHE BAY. HAWAII. JUNE 16, 1982 TWENTY-EIGHT PAGES If it NI, Marines rescue fishermen 11 NOR F PREPARE (i') drifted very close to the fiery vessel, so Wright and Lance Corporal Joel by Sgts Pepper Davis 13 L 1; they pushed it away with the rotors. Sauder, SAR swimmers, were able to and Chris Tonegatto "We talked about it and decided to bring the remaining victims to safety try to get them out with the horse within an hour after leaving the air ALli,! Five fishe'rmen were rescued from collar. Corporal (Mike) Murphy (crew station. Lq. nle. the ocean Thursday afternoon by the chief) lowered it, and one of the guys Bongyong Park, 34, captain of the pilots and crews of Marine Medium left the raft and swam to the collar. vessel Pan Am I; passengers Kim Helicopter Squadron-265, and Station After we hoisted him up, the collar was Chekun, 39; Jin Samseon, 32; and Operations Maintenance Squadron. lowered again, but nobody wanted to Heyun Oh, 21, all of Kalihi, were According to Captain Vincent chance leaving the raft to swim to it," treated for minor burns and abrasions Palencia, '265 pilot, he and his copilot, commented Palencia. and released. First Lieutenant Kelly Ellis, were Ellis added: "Our rotor wash kept conducting a functional check flight pushing the raft around and we had to Park explained that the fire started around 3:30 p.m., when they noticed a keep chasing it, so we gave it up." in the engine room around 2:30 p.m. -

Community Guide Activities and Tips to Build Resilience Skills with Children and Families Community Guide a Creation Of

Community Guide Activities and tips to build resilience skills with children and families Community Guide A creation of Little Children, Big Challenges: Senior Vice President, Outreach and Educational Practices: Jeanette Betancourt, Ed.D.; Vice President, Outreach Initiatives and Partners: Lynn The nonprofit educational organization behind Chwatsky; Senior Director, Outreach and Content Design: María del Rocío Galarza; Sesame Street and so much more Curriculum Specialist: Brittany Sommer; Director, Content: Jennifer Schiffman; Project Manager: Christina App; Project Coordinator: Angela Hong; Project Assistant: Andrea Sesame Workshop is the nonprofit educational organization that revolutionized children’s Cody; Spanish Language Editor and Content Manager: Helen Cuesta; Spanish Translator: television programming with the landmark Sesame Street. The Workshop produces local Mario Chávez; Spanish Proofreader: Rosario (Charo) Welle; Director, Domestic Research: Sesame Street programs, seen in over 150 countries, and other acclaimed shows to help David Cohen; Director, Project Finance: Carole Schechner; Writers: Joshua Briggs and bridge the literacy gap, including The Electric Company. Beyond television, the Workshop Rebecca Honig-Briggs; Copy Editor: Diane Rothschild; Proofreader: Evelyn Shoop; produces content for multiple media platforms on a wide range of issues including literacy, Vice President, Creative Services: Theresa Fitzgerald; Production Director, Creative, health, and military deployment. Initiatives meet specific needs to help -

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a Short Story by Jeffrey Eugenides

Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci, with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides Author Marcoci, Roxana Date 2005 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 0870700804 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/116 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art museumof modern art lIOJ^ArxxV^ 9 « Thomas Demand Thomas Demand Roxana Marcoci with a short story by Jeffrey Eugenides The Museum of Modern Art, New York Published in conjunction with the exhibition Thomas Demand, organized by Roxana Marcoci, Assistant Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 4-May 30, 2005 The exhibition is supported by Ninah and Michael Lynne, and The International Council, The Contemporary Arts Council, and The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. This publication is made possible by Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro. Produced by the Department of Publications, The Museum of Modern Art, New York Edited by Joanne Greenspun Designed by Pascale Willi, xheight Production by Marc Sapir Printed and bound by Dr. Cantz'sche Druckerei, Ostfildern, Germany This book is typeset in Univers. The paper is 200 gsm Lumisilk. © 2005 The Museum of Modern Art, New York "Photographic Memory," © 2005 Jeffrey Eugenides Photographs by Thomas Demand, © 2005 Thomas Demand Copyright credits for certain illustrations are cited in the Photograph Credits, page 143. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004115561 ISBN: 0-87070-080-4 Published by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, New York 10019-5497 (www.moma.org) Distributed in the United States and Canada by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, New York Distributed outside the United States and Canada by Thames & Hudson Ltd., London Front and back covers: Window (Fenster). -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace.