Report Small House Eng23 4.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Recognized Villages Under the New Territories Small House Policy

LIST OF RECOGNIZED VILLAGES UNDER THE NEW TERRITORIES SMALL HOUSE POLICY Islands North Sai Kung Sha Tin Tuen Mun Tai Po Tsuen Wan Kwai Tsing Yuen Long Village Improvement Section Lands Department September 2009 Edition 1 RECOGNIZED VILLAGES IN ISLANDS DISTRICT Village Name District 1 KO LONG LAMMA NORTH 2 LO TIK WAN LAMMA NORTH 3 PAK KOK KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 4 PAK KOK SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 5 SHA PO LAMMA NORTH 6 TAI PENG LAMMA NORTH 7 TAI WAN KAU TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 8 TAI WAN SAN TSUEN LAMMA NORTH 9 TAI YUEN LAMMA NORTH 10 WANG LONG LAMMA NORTH 11 YUNG SHUE LONG LAMMA NORTH 12 YUNG SHUE WAN LAMMA NORTH 13 LO SO SHING LAMMA SOUTH 14 LUK CHAU LAMMA SOUTH 15 MO TAT LAMMA SOUTH 16 MO TAT WAN LAMMA SOUTH 17 PO TOI LAMMA SOUTH 18 SOK KWU WAN LAMMA SOUTH 19 TUNG O LAMMA SOUTH 20 YUNG SHUE HA LAMMA SOUTH 21 CHUNG HAU MUI WO 2 22 LUK TEI TONG MUI WO 23 MAN KOK TSUI MUI WO 24 MANG TONG MUI WO 25 MUI WO KAU TSUEN MUI WO 26 NGAU KWU LONG MUI WO 27 PAK MONG MUI WO 28 PAK NGAN HEUNG MUI WO 29 TAI HO MUI WO 30 TAI TEI TONG MUI WO 31 TUNG WAN TAU MUI WO 32 WONG FUNG TIN MUI WO 33 CHEUNG SHA LOWER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 34 CHEUNG SHA UPPER VILLAGE SOUTH LANTAU 35 HAM TIN SOUTH LANTAU 36 LO UK SOUTH LANTAU 37 MONG TUNG WAN SOUTH LANTAU 38 PUI O KAU TSUEN (LO WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 39 PUI O SAN TSUEN (SAN WAI) SOUTH LANTAU 40 SHAN SHEK WAN SOUTH LANTAU 41 SHAP LONG SOUTH LANTAU 42 SHUI HAU SOUTH LANTAU 43 SIU A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 44 TAI A CHAU SOUTH LANTAU 3 45 TAI LONG SOUTH LANTAU 46 TONG FUK SOUTH LANTAU 47 FAN LAU TAI O 48 KEUNG SHAN, LOWER TAI O 49 KEUNG SHAN, -

Right to Adequate Housing There Were No Recommendations Made on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (HKSAR) in the Second UPR Cycle

Right to Adequate Housing There were no recommendations made on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (HKSAR) in the Second UPR Cycle. Framework in HKSAR HKSAR is the most expensive city, worldwide, in which to buy a home. Broadly, housing is categorized into; permanent private housing, public rental housing, and public housing. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) has been extended to HKSAR and its implementation is covered under Article 39 of the Basic Law. The middle income group is squeezed by the rocketing prices, relative to low incomes; particularly given that there is no control to prevent public rental rates being set against the wider commercial property market. The crisis in the affordability of housing in Hong Kong has been noted by successive Chief Executives since 2013. For example, the current Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, said in her Policy Address in October 2017 that “meeting the public’s housing needs is our top priority”. However, despite these statements, since 2013 there has been a continued surge in property prices, rental prices and an increase in the number of homeless. Concerns with the lack of affordable and adequate housing were raised by the ICESCR Committee in their 2014 Concluding Observations on HKSAR. Challenges Cases, facts and comments • The government has not taken • Median property prices are 19.4 times the median sufficient action to protect and salary. promote the right to adequate housing • In the years 2007-2016, property prices in HKSAR under Article 11(1) of ICESCR, including increased by 176.4%, compared to a 42.9% rise in the right to choose one’s residence the median monthly income. -

1171 20180510 AM Final Draft-Clean

Minutes of 1171st Meeting of the Town Planning Board held on 10.5.2018 Present Permanent Secretary for Development Chairperson (Planning and Lands) Ms Bernadette H.H. Linn Professor S.C. Wong Vice-Chairperson Mr Ivan C.S. Fu Mr Sunny L.K. Ho Mr Stephen H.B. Yau Mr David Y.T. Lui Dr Frankie W.C. Yeung Mr Peter K.T. Yuen Dr Lawrence W.C. Poon Mr Wilson Y.W. Fung Mr Thomas O.S. Ho Mr Alex T.H. Lai Professor T.S. Liu Ms Sandy H.Y. Wong Mr Franklin Yu Mr L.T. Kwok - 2 - Mr Daniel K.S. Lau Mr K.W. Leung Professor John C.Y. Ng Professor Jonathan W.C. Wong Assistant Director (Environmental Assessment) Environmental Protection Department Mr C.F. Wong Assistant Director (Regional 1) Lands Department Mr Simon S.W. Wang Chief Engineer (Works) Home Affairs Department Mr Martin W.C. Kwan Chief Traffic Engineer (New Territories East) Transport Department Mr Ricky W.K. Ho Deputy Director of Planning/District Secretary Ms Jacinta K.C. Woo Absent with Apologies Mr Lincoln L.H. Huang Mr H.W. Cheung Dr F.C. Chan Mr Philip S.L. Kan Mr K.K. Cheung Dr C.H. Hau Dr Lawrence K.C. Li Mr Stephen L.H. Liu Miss Winnie W.M. Ng - 3 - Mr Stanley T.S. Choi Ms Lilian S.K. Law Dr Jeanne C.Y. Ng Mr Ricky W.Y. Yu Director of Planning Mr Raymond K.W. Lee In Attendance Assistant Director of Planning/Board Ms April K.Y. -

The Unruly New Territories

The Unruly New Territories Small Houses, Ancestral Estates, Illegal Structures, and Other Customary Land Practices of Rural Hong Kong Malcolm Merry Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong https://hkupress.hku.hk © 2020 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8528-32-5 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents 1. An Unruly Territory 1 2. Treaty, Takeover, and Trouble 13 3. Land Survey and Settlement 24 4. Profile of a Territory 36 5. Preservation of Custom 53 6. Customary Landholding: Skin and Bones 74 7. Customary Transfer of Land 87 8. Customary Institutions 106 9. Regulation of Customary Institutions 134 10. Small Houses 159 11. The Small House Policy 181 12. Exploitation of Ding Rights 196 13. Lawfulness of the Policy 209 14. Article 40 219 15. Property Theft 237 16. Illegal Structures 259 17. Despoliation 269 Acknowledgements 281 Index 282 1 An Unruly Territory Ever since incorporation into Hong Kong at the end of the nineteenth century, the New Territories have been causing trouble. Initially that was in the form of armed resistance to the British takeover of April 1899. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

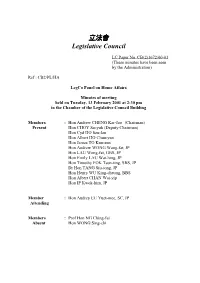

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)1672/00-01 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB2/PL/HA LegCo Panel on Home Affairs Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday, 13 February 2001 at 2:30 pm in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members : Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo (Chairman) Present Hon CHOY So-yuk (Deputy Chairman) Hon Cyd HO Sau-lan Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon Andrew WONG Wang-fat, JP Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, SBS, JP Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP Hon Henry WU King-cheong, BBS Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon IP Kwok-him, JP Member : Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Attending Members : Prof Hon NG Ching-fai Absent Hon WONG Sing-chi - 2 - Public Officers : Item IV Attending Mr Leo KWAN Deputy Secretary for Home Affairs (1) Mr Charles CHAN Principal Assistant Secretary for Home Affairs Mr C M WONG Assistant Secretary for Home Affairs Mr Stephen PANG Commissioner for Rehabilitation Mr David WONG Principal Assistant Secretary for Security Mr Duncan PESCOD Deputy Secretary for the Civil Service Mr Gary YEUNG Principal Assistant Secretary for Planning and Lands (Lands) Mr KWOK Leung-ming Assistant Commissioner of Correctional Services (Human Resources) Mr TANG King-shing Assistant Commissioner of Police (Personnel) Mrs CHAN MAK Kit-ling Assistant Commissioner for Labour Mrs LAI NG Suet-mui Chief Housing Manager (Applications) Housing Department Item V Mr Leo KWAN Deputy Secretary for Home Affairs (1) - 3 - Mr John DEAN Principal Assistant Secretary -

Executive Summary Research Report on Abuse of Small House Policy by Selling Ding Rights

Executive Summary Research report on abuse of small house policy by selling Ding Rights ● The 2015 small house development scam was just a tip of an iceberg: in December 2015, 11 NT Indigenous Villagers were sent to jail for having deceived the Lands Department in order to obtain approvals to build small houses, while what they only wanted was to sell their “ding” rights to developers who turned them into Spanish villas for profits. One could realise the pervasiveness of similar scams by visiting the many NT villages, although its illegality was repeatedly stated by the government. ● The abuse must be curbed: Since 1972, the Small House Policy has caused many problems thanks to the loopholes by which the developers exploit through recruiting villagers who exercise their exclusive “ding” rights. Such practice breaches the original policy intent, not to mention the alleged illegality. However the government appears to be reluctant on reforming the policy. ● Database on “Ding” house villas: Government data on the abuse of the policy is incomplete and scattered. The public, although aware of the rampant abuse, cannot state the exact nature and seriousness of the problem due to the absence of relevant data. This would not help realising policy changes. To give a head start, Liber Research Community has completed a comprehensive database on “Ding” house villas, depicting the number of suspected abuse cases. Link to Database: https://goo.gl/6DTvFn (In Chinese only) ● 1 in every 4 small houses abused: The research team has found at least 9 878 small houses that were built through suspected frontman scheme, through the use of a combination of map tools, paying site visits, analysing judgments of civil court cases, and performing land registry searches. -

Revamping Tradition: Contested Politics of 'The

Revamping Tradition: Contested Politics of ‘The Indigenous’ in Postcolonial Hong Kong 83 Part II People: Whose Indigenity? 84 Whose Tradition? Revamping Tradition: Contested Politics of ‘The Indigenous’ in Postcolonial Hong Kong 85 Chapter 4 Revamping Tradition: Contested Politics of ‘The Indigenous’ in Postcolonial Hong Kong Shu-Mei Huang [Yet] it was unthinkable that anyone not of the village clan could build a house in a village. Denis Bray (2001, p. 164) Using the past, present, and future to emphasize each other is common in commemorations. John Carroll (2005, p. 165) On lunar New Year’s Eve, 2012, the chairman of the Heung Yee Kuk (HYK), Wong-fat Lau, made a drawing in the Che Kung Temple in the presence of many of the elite in the New Territories (NT) – a symbolic gesture to welcome the New Year in Hong Kong. The poem in the drawing read, ‘What is evil and what is divine? It’s so hard to differentiate the evil from the divine’. Chairman Lau was subsequently bombarded by questions from the media about whether the poem alluded to the then-serious competition for Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Lau laughed, without giving any explicit message. About 2 years earlier, during mid-October 2010, I had happened to attend a community meeting in the soon-to-be-demolished village of Choi Yuen. Some sixty people had gathered to witness a significant phone call to Lau, in which the villagers were trying to obtain his assistance in negotiating a right-of-way to enable their relocation plan. -

The Making of Rurality in Hong Kong : Villagers' Changing Perception of Rural Space

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Sociology and Social Policy 4-8-2015 The making of rurality in Hong Kong : villagers' changing perception of rural space Chun On LAI Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/soc_etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lai, C. O. (2015). The making of rurality in Hong Kong: Villagers' changing perception of rural space (Master's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/soc_etd/39/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology and Social Policy at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE MAKING OF RURALITY IN HONG KONG: VILLAGERS’ CHANGING PERCEPTION OF RURAL SPACE LAI CHUN ON MPHIL LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2015 THE MAKING OF RURALITY IN HONG KONG: VILLAGERS’ CHANGING PERCEPTION OF RURAL SPACE by LAI Chun On A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Social Sciences (Sociology) Lingnan University 2015 ABSTRACT The Making of Rurality in Hong Kong: Villagers’ Changing Perception of Rural Space by LAI Chun On Master of Philosophy The study focus on the ongoing disputes over rural development bring to the fore the competing paradigms and representations of rurality on the part of different rural stakeholders in the New Territories. -

Chapter 8 the Government of the Hong Kong Special

CHAPTER 8 THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION CAPITAL WORKS RESERVE FUND GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT Housing, Planning and Lands Bureau GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENT Lands Department Small house grants in the New Territories Audit Commission Hong Kong 15 October 2002 SMALL HOUSE GRANTS IN THE NEW TERRITORIES Contents Paragraphs SUMMARY AND KEY FINDINGS PART 1: INTRODUCTION Background 1.1 – 1.5 Audit review 1.6 PART 2: IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SMALL HOUSE POLICY 2.1 – 2.3 Restriction on alienation of small houses 2.4 – 2.7 Removal of restriction on alienation 2.8 – 2.9 Cases of removal of restriction on alienation 2.10 – 2.12 Concern raised by the Court of Appeal 2.13 – 2.14 Lands D’s actions to address the problem of 2.15 – 2.20 selling the small house right Audit observations on the implementation of 2.21 – 2.24 the small house policy Audit recommendations on the implementation of 2.25 the small house policy Response from the Administration 2.26 – 2.27 PART 3: CHECKING OF INDIGENOUS VILLAGER STATUS 3.1 Indigenous villager status of small house grant applicants 3.2 – 3.4 Checking of indigenous villager status 3.5 – 3.6 Audit observations on checking of indigenous villager status 3.7 – 3.8 — i — Paragraphs Checking of doubtful cases 3.9 – 3.11 Audit observations on checking of doubtful cases 3.12 Audit recommendations on checking of indigenous villager status 3.13 Response from the Administration 3.14 PART 4: PREMIUM ON REMOVAL OF 4.1 RESTRICTION ON ALIENATION Small house grant conditions 4.2 – 4.3 Premium computation inconsistent -

The Female Inheritance Movement in Hong Kong

Current Anthropology Volume 46, Number 3, June 2005 ᭧ 2005 by The Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. All rights reserved 0011-3204/2005/4603-0002$10.00 tice and Getting Even (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), and Urban Danger (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981). She is currently completing a book on international hu- The Female man rights and localization processes. rachel e. stern is a Ph.D. student in the Political Science Inheritance Movement Department at the University of California, Berkeley, and a Na- tional Science Foundation Graduate Fellow. Her previous publications include articles in Asian Survey and the China En- in Hong Kong vironment Series. Her current research deals with environmental activism in China. The present paper was submitted 28 x 03 and accepted 4 viii 04. Theorizing the Local/Global In the spring of 1994, everyone in Hong Kong was talking Interface1 about female inheritance. Women in the New Territories were subject to Chinese customary law and, under Brit- ish colonialism, still unable to inherit land. That year, a group of rural indigenous women joined forces with by Sally Engle Merry and Hong Kong women’s groups to demand legal change. In the plaza in front of the Legislative Council building, Rachel E. Stern amid shining office buildings, the indigenous women, dressed in the oversized hats of farm women, sang folk laments with new lyrics about injustice and inequality. Demonstrators from women’s groups made speeches Human rights concepts dominate discussions about social justice about gender equality and, at times, tore paper chains at the global level, but how much local communities have from their necks to symbolize liberation from Chinese adopted this language and what it means to them are far less customary law (Chan 1995:4). -

The Female Inheritance Movement in Hong Kong

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Unpacking Adaptation: The Female Inheritance Movement in Hong Kong Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7jr115jr Journal Mobilization, 10(3) ISSN 1086-671X Author Stern, Rachel E. Publication Date 2005-10-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNPACKING ADAPTATION: THE FEMALE INHERITANCE MOVEMENT IN HONG KONG* Rachel E. Stern† In 1994, after a year of intense activism by indigenous women and their urban supporters, indigenous women in the New Territories of Hong Kong were legally allowed to inherit land for the first time. In pushing for legislative change, the female inheritance movement adopted key ideas—gender equality, human rights and a critique of patriarchy—from a global vocabulary of feminism and human rights. This article examines this rights frame to understand how, if at all, activists modified international conceptions of discrimination and rights to fit Hong Kong. Overall, the ideology was not fundamentally altered or adapted, but indigenized by local activists through the use of local symbols. More deep-rooted change was not necessary for two reasons: First, in the pre-handover moment, rights arguments derived political currency from their asso- ciation with an international community. Also, critical movement participants, here termed translators, helped encompass the indigenous women’s individual kinship grievances within a broader movement based on rights. In 1993, Hong Kong was engulfed in a debate over female inheritance in the New Territories, a relatively rural area just across the border from Mainland China.1 Female inheritance was discussed on talk shows, in classrooms and around dinner tables. -

Chapter 4 Small House Grants in the New Territories

Chapter 4 Small house grants in the New Territories Audit conducted a review of the Lands Department’s implementation of the small house policy in the New Territories and identified areas where improvements could be made. Need to improve the implementation of the small house policy 2. The Committee noted that in the present review, Audit made the same observation as in its 1987 audit review, that the problem of indigenous villagers selling their small houses soon after the issue of the certificates of compliance (CCs) still existed. Audit found that in 53 cases, the indigenous villagers applied for permission to sell their small houses within an average of three days after the issue of the CCs. Nearly all of the flats of the 53 small houses were sold in about five months after the removal of the restriction on alienation. Audit considered that many indigenous villagers were cashing in on their eligibility for the small house concessionary grants, which the Government considered to be a valuable privilege especially in a rising property market. In June 2001, the Court of Appeal drew the Lands Department’s attention to the issue of alleged illegal agreements on small house grant applications. The Lands Department noted the problem and had taken some actions to address it. 3. The Committee wondered: - whether the problems above constituted an abuse of the privilege to develop small houses, as indigenous villagers were cashing in on their eligibility for concessionary grants; and - whether these problems arose from omission of actions which should have been taken by the Lands Department.