Chapter 3: Natural Heritage Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Saskatchewan River Watershed Authority Watershed Stewards Inc

Saskatchewan South Saskatchewan River Watershed Authority Watershed Stewards Inc. Table of Contents 1. Comments from Participants 1 1.1 A message from your Watershed Advisory Committees 1 2. Watershed Protection and You 2 2.1 One Step in the Multi-Barrier Approach to Drinking Water Protection 2 2.2 Secondary Benefits of Protecting Source Water: Quality and Quantity 3 3. South Saskatchewan River Watershed 4 4. Watershed Planning Methodology 5 5. Interests and Issues 6 6. Planning Objectives and Recommendations 7 6.1 Watershed Education 7 6.2 Providing Safe Drinking Water to Watershed Residents 8 6.3 Groundwater Threats and Protection 10 6.4 Gravel Pits 12 6.5 Acreage Development 13 6.6 Landfills (Waste Disposal Sites) 14 6.7 Oil and Gas Exploration, Development, Pipelines and Storage 17 6.8 Effluent Releases 18 6.9 Lake Diefenbaker Water Levels and the Operation of Gardiner Dam 20 6.10 Watershed Development 22 6.11 Water Conservation 23 6.12 Stormwater Discharge 23 6.13 Water Quality from Alberta 25 6.14 Agriculture Activities 26 6.15 Fish Migration and Habitat 27 6.16 Role of Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Saskatchewan 28 6.17 Wetland Conservation 29 6.18 Opimihaw Creek Flooding 31 6.19 Federal Lands 32 7. Implementation Strategy 33 8. Measuring Plan Success - The Yearly Report Card 35 9. Conclusion 36 10. Appendices 37 Courtesy of Ducks Unlimited Canada 1. Comments from Participants 1.1 A message from your Watershed Advisory Committees North “Safe drinking water and a good supply of water are important to ALL citizens. -

Fisheries Barriers in Native Trout Drainages

Alberta Conservation Association 2018/19 Project Summary Report Project Name: Fisheries Barriers in Native Trout Drainages Fisheries Program Manager: Peter Aku Project Leader: Scott Seward Primary ACA Staff on Project: Jason Blackburn, David Jackson, and Scott Seward Partnerships Alberta Environment and Parks Environment and Climate Change Canada Key Findings • We compiled existing barrier location information within the Peace River, Athabasca River, North Saskatchewan River, and Red Deer River basins into a centralized database. • We catalogued fish habitat and community data for the Narraway River watershed for use in a population restoration feasibility framework. • We identified 107 potential barrier locations within the Narraway River watershed, using Google Earth ©, which will be refined using valley confinement modeling and validated with ground truthing in 2019. Introduction Invasive species pose one of the greatest threats to Alberta native trout species, through hybridization, competition, and displacement. These threats are partially mediated by the presence of natural headwater fish-passage barriers, namely waterfalls, that impede upstream 1 invasions. In Alberta, several sub-populations of native trout remain genetically pure primarily because of waterfalls. Identification and inventory of waterfalls in the Peace River, Athabasca River, North Saskatchewan River, and Red Deer River basins isolating pure populations and their habitats is critical to inform population recovery and build implementation strategies on a stream by stream basis. For example, historical stocking of non-native trout to the Narraway River watershed may be endangering native bull trout and Arctic grayling. Non-native cutthroat trout, rainbow trout, and brook trout have been stocked in the Torrens River, Stetson Creek, and Two Lakes, all of which have connectivity to the Narraway River. -

The Environment

background The Environment Cities across Canada and internationally are developing greener ways of building and powering communities, housing and infrastructure. They are also growing their urban forests, protecting wetlands and improving the quality of water bodies. The history of Saskatoon is tied to the landscape through agriculture and natural resources. The South Saskatchewan River that flows through the city is a cherished space for both its natural functions and public open space. Saskatonians value their environment. However, the ecological footprint of Saskatoon is relatively large. Our choices of where we live, how we travel around the city and the way that we use energy at home all have an impact on the health of the environment. The vision for Saskatoon needs to consider many aspects of the natural environment, from energy and air quality to water and trees. Our ecological footprint Energy sources Cities consume significant quantities of resources and Over half of Saskatoon’s ecological footprint is due to have a major impact on the environment, well beyond their energy use. As Saskatoon is located in a northern climate, borders. One way of describing the impact of a city is to there is a need for heating in the winter. As well, most measure its ecological footprint. The footprint represents Saskatoon homes are heated by natural gas. Although the land area necessary to sustain current levels of natural gas burns cleaner than coal and oil it produces resource consumption and waste discharged by that CO2, a greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere, making it an population. A community consumes material, water, and unsustainable energy source and the supply of natural gas energy, processes them into usable forms, and generates is limited. -

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Submitted to: Submitted by: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Steering Committee a Division of AMEC Americas Limited Lethbridge, Alberta Lethbridge, Alberta 2014 amec.com WATER STORAGE OPPORTUNITIES IN THE SOUTH SASKATCHEWAN RIVER BASIN IN ALBERTA Submitted to: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Lethbridge, Alberta Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 CW2154 SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 Executive Summary Water supply in the South Saskatchewan River Basin (SSRB) in Alberta is naturally subject to highly variable flows. Capture and controlled release of surface water runoff is critical in the management of the available water supply. In addition to supply constraints, expanding population, accelerating economic growth and climate change impacts add additional challenges to managing our limited water supply. The South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009) identified re-management of existing reservoirs and the development of additional water storage sites as potential solutions to reduce the risk of water shortages for junior license holders and the aquatic environment. Modelling done as part of that study indicated that surplus water may be available and storage development may reduce deficits. This study is a follow up on the major conclusions of the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009). It addresses the provincial Water for Life goal of “reliable, quality water supplies for a sustainable economy” while respecting interprovincial and international apportionment agreements and other legislative requirements. -

South Saskatchewan River Legal and Inter-Jurisdictional Institutional Water Map

South Saskatchewan River Legal and Inter-jurisdictional Institutional Water Map. Derived by L. Patiño and D. Gauthier, mainly from Hurlbert, Margot. 2006. Water Law in the South Saskatchewan River Basin. IACC Project working paper No. 27. March, 2007. May, 2007. Brief Explanation of the South Saskatchewan River Basin Legal and Inter- jurisdictional Institutional Water Map Charts. This document provides a brief explanation of the legal and inter-jurisdictional water institutional map charts in the South Saskatchewan River Basin (SSRB). This work has been derived from Hurlbert, Margot. 2006. Water Law in the South Saskatchewan River Basin. IACC Project working paper No. 27. The main purpose of the charts is to provide a visual representation of the relevant water legal and inter-jurisdictional institutions involved in the management, decision-making process and monitoring/enforcement of water resources (quality and quantity) in Saskatchewan and Alberta, at the federal, inter-jurisdictional, provincial and local levels. The charts do not intend to provide an extensive representation of all water legal and/or inter-jurisdictional institutions, nor a comprehensive list of roles and responsibilities. Rather to serve as visual tools that allow the observer to obtain a relatively prompt working understanding of the current water legal and inter-jurisdictional institutional structure existing in each province. Following are the main components of the charts: 1. The charts provide information regarding water quantity and water quality. To facilitate a prompt reading between water quality and water quantity the charts have been colour coded. Water quantity has been depicted in red (i.e., text, boxes, link lines and arrows), and contains only one subdivision, water allocation. -

Land Use, Climate Change and Ecological Responses in the Upper

Land use, climate change and ecological responses in the Upper North 1 Saskatchewan and Red Deer River Basins: A scientific assessment Land use, climate change and ecological responses in the Upper North Saskatchewan and Red Deer River Basins: A scientific assessment Dan Farr, Colleen Mortimer, Faye Wyatt, Andrew Braid, Charlie Loewen, Craig Emmerton, Simon Slater Cover photo: Wayne Crocker This publication can be found at: open.alberta.ca/publications/9781460140697. Comments, questions, or suggestions regarding the content of this document may be directed to: Ministry of Environment and Parks, Environmental Monitoring and Science Division 10th Floor, 9888 Jasper Avenue NW, Edmonton, Alberta, T5J 5C6 Tel: 780-229-7200 Toll Free: 1-844-323-6372 Fax: 780-702-0169 Email: [email protected] Media Inquiries: [email protected] Website: environmentalmonitoring.alberta.ca Recommended citation: Farr. D., Mortimer, C., Wyatt, F., Braid, A., Loewen, C., Emmerton, C., and Slater, S. 2018. Land use, climate change and ecological responses in the Upper North Saskatchewan and Red Deer River Basins: A scientific assessment. Government of Alberta, Ministry of Environment and Parks. ISBN 978-1-4601-4069-7. Available at: open.alberta.ca/publications/9781460140697. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta, as represented by the Minister of Alberta Environment and Parks, 2018. This publication is issued under the Open Government Licence - Alberta open.alberta.ca/licence. Published September 2018 ISBN 978-1-4601-4069-7 Land use, climate change and ecological responses in the Upper North 2 Saskatchewan and Red Deer River Basins: A scientific assessment Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to the external reviewers for providing their technical reviews and feedback, which have enhanced this work. -

South Saskatchewan River Basin Adaptation to Climate Variability Project

South Saskatchewan River Basin Adaptation to Climate Variability Project Climate Variability and Change in the Bow River Basin Final Report June 2013 This study was commissioned for discussion purposes only and does not necessarily reflect the official position of the Climate Change Emissions Management Corporation, which is funding the South Saskatchewan River Basin Adaptation to Climate Variability Project. The report is published jointly by Alberta Innovates – Energy and Environment Solutions and WaterSMART Solutions Ltd. This report is available and may be freely downloaded from the Alberta WaterPortal website at www.albertawater.com. Disclaimer Information in this report is provided solely for the user’s information and, while thought to be accurate, is provided strictly “as is” and without warranty of any kind. The Crown, its agents, employees or contractors will not be liable to you for any damages, direct or indirect, or lost profits arising out of your use of information provided in this report. Alberta Innovates – Energy and Environment Solutions (AI-EES) and Her Majesty the Queen in right of Alberta make no warranty, express or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information contained in this publication, nor that use thereof infringe on privately owned rights. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of AI-EES or Her Majesty the Queen in right of Alberta. The directors, officers, employees, agents and consultants of AI-EES and the Government of Alberta are exempted, excluded and absolved from all liability for damage or injury, howsoever caused, to any person in connection with or arising out of the use by that person for any purpose of this publication or its contents. -

North Saskatchewan River Drainage, Fish Sustainability Index Data Gaps Project, 2015

North Saskatchewan River Drainage, Fish Sustainability Index Data Gaps Project, 2015 The Alberta Conservation Association is a Delegated Administrative Organization under Alberta’s Wildlife Act. North Saskatchewan River Drainage, Fish Sustainability Index Data Gaps Project, 2015 Mike Rodtka, Chad Judd and Andrew Clough Alberta Conservation Association 101 – 9 Chippewa Road Sherwood Park, Alberta, Canada T8A 6J7 Report Editors PETER AKU KELLEY KISSNER Alberta Conservation Association 50 Tuscany Meadows Cr. NW 101 – 9 Chippewa Rd. Calgary, AB T3L 2T9 Sherwood Park, AB T8A 6J7 Conservation Report Series Type Data ISBN: 978-0-9949118-3-4 Disclaimer: This document is an independent report prepared by Alberta Conservation Association. The authors are solely responsible for the interpretations of data and statements made within this report. Reproduction and Availability: This report and its contents may be reproduced in whole, or in part, provided that this title page is included with such reproduction and/or appropriate acknowledgements are provided to the authors and sponsors of this project. Suggested Citation: Rodtka, M., C. Judd, and A. Clough. 2016. North Saskatchewan River drainage, Fish Sustainability Index data gaps project, 2015. Data Report, D-2016-105, produced by Alberta Conservation Association, Sherwood Park, Alberta, Canada. 17 pp + App. Cover photo credit: David Fairless Digital copies of conservation reports can be obtained from: Alberta Conservation Association 101 – 9 Chippewa Rd. Sherwood Park, AB T8A 6J7 Toll Free: 1-877-969-9091 Tel: (780) 410-1998 Fax: (780) 464-0990 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ab-conservation.com i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Alberta Environment and Parks Fish Sustainability Index is a standardized process of assessment that provides a landscape-level overview of fish sustainability within the province and enables broad-scale evaluation of management actions and land-use planning. -

Water Quality in the South SK River Basin

Water Quality in the South SK River Basin I AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SOUTH SASKATCHEWAN RIVER BASIN I.1 The Saskatchewan River Basin The South Saskatchewan River joins the North Saskatchewan River to form one of the largest river systems in western Canada, the Saskatchewan River System, which flows from the headwater regions along the Rocky Mountains of south-west Alberta and across the prairie provinces of Canada (Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba). The Prairie physiographic region is characterized by rich soils, thick glacial drift and extensive aquifer systems, and a consistent topography of broad rolling hills and low gradients which create isolated surface wetlands. In contrast, the headwater region of the Saskatchewan River (the Western Cordillera physiographic region) is dominated by thin mineral soils and steep topography, with highly connected surface drainage systems and intermittent groundwater contributions to surface water systems. As a result, the Saskatchewan River transforms gradually in its course across the provinces: from its oxygen-rich, fast flowing and highly turbid tributaries in Alberta to a meandering, nutrient-rich and biologically diverse prairie river in Saskatchewan. There are approximately 3 million people who live and work in the Saskatchewan River Basin and countless industries which operate in the basin as well, including pulp and paper mills, forestry, oil and gas extraction, mining (coal, potash, gravel, etc.), and agriculture. As the fourth longest river system in North America, the South Saskatchewan River Basin covers an incredibly large area, draining a surface of approximately 405 860 km² (Partners FOR the Saskatchewan River Basin, 2009). Most of the water that flows in the Saskatchewan River originates in the Rocky Mountains of the Western Cordillera, although some recharge occurs in the prairie regions of Alberta and Saskatchewan through year-round groundwater contributions, spring snow melt in March or April, and summer rainfall in May and early July (J.W. -

Northern Leopard Frog Recovery Program

Northern Leopard Frog Recovery Program Year 5 (2003) Kris Kendell In cooperation with: Northern Leopard Frog Recovery Program Year 5 (2003) This publication may be cited as: Kendell, K. 2004. Northern leopard frog recovery program: Year 5 (2003). Unpublished report, Alberta Conservation Association, Edmonton, AB. 14 pp. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ v 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 STUDY AREA ......................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Egg mass collection and frog release sites........................................................................ 2 2.2 Captive rearing site ........................................................................................................... 2 3.0 METHODS ............................................................................................................................... 3 3.1 Captive rearing.................................................................................................................. 3 3.2 Marking............................................................................................................................. 3 3.3 Release (2003) ................................................................................................................. -

Quaternary and Late Tertiary of Montana: Climate, Glaciation, Stratigraphy, and Vertebrate Fossils

QUATERNARY AND LATE TERTIARY OF MONTANA: CLIMATE, GLACIATION, STRATIGRAPHY, AND VERTEBRATE FOSSILS Larry N. Smith,1 Christopher L. Hill,2 and Jon Reiten3 1Department of Geological Engineering, Montana Tech, Butte, Montana 2Department of Geosciences and Department of Anthropology, Boise State University, Idaho 3Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Billings, Montana 1. INTRODUCTION by incision on timescales of <10 ka to ~2 Ma. Much of the response can be associated with Quaternary cli- The landscape of Montana displays the Quaternary mate changes, whereas tectonic tilting and uplift may record of multiple glaciations in the mountainous areas, be locally signifi cant. incursion of two continental ice sheets from the north and northeast, and stream incision in both the glaciated The landscape of Montana is a result of mountain and unglaciated terrain. Both mountain and continental and continental glaciation, fl uvial incision and sta- glaciers covered about one-third of the State during the bility, and hillslope retreat. The Quaternary geologic last glaciation, between about 21 ka* and 14 ka. Ages of history, deposits, and landforms of Montana were glacial advances into the State during the last glaciation dominated by glaciation in the mountains of western are sparse, but suggest that the continental glacier in and central Montana and across the northern part of the eastern part of the State may have advanced earlier the central and eastern Plains (fi gs. 1, 2). Fundamental and retreated later than in western Montana.* The pre- to the landscape were the valley glaciers and ice caps last glacial Quaternary stratigraphy of the intermontane in the western mountains and Yellowstone, and the valleys is less well known. -

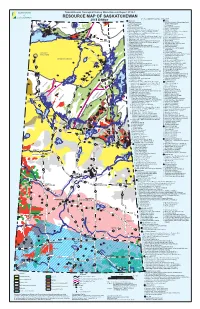

Mineral Resource Map of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Geological Survey Miscellaneous Report 2018-1 RESOURCE MAP OF SASKATCHEWAN KEY TO NUMBERED MINERAL DEPOSITS† 2018 Edition # URANIUM # GOLD NOLAN # # 1. Laird Island prospect 1. Box mine (closed), Athona deposit and Tazin Lake 1 Scott 4 2. Nesbitt Lake prospect Frontier Adit prospect # 2 Lake 3. 2. ELA prospect TALTSON 1 # Arty Lake deposit 2# 4. Pitch-ore mine (closed) 3. Pine Channel prospects # #3 3 TRAIN ZEMLAK 1 7 6 # DODGE ENNADAI 5. Beta Gamma mine (closed) 4. Nirdac Creek prospect 5# # #2 4# # # 8 4# 6. Eldorado HAB mine (closed) and Baska prospect 5. Ithingo Lake deposit # # # 9 BEAVERLODGE 7. 6. Twin Zone and Wedge Lake deposits URANIUM 11 # # # 6 Eldorado Eagle mine (closed) and ABC deposit CITY 13 #19# 8. National Explorations and Eldorado Dubyna mines 7. Golden Heart deposit # 15# 12 ### # 5 22 18 16 # TANTATO # (closed) and Strike deposit 8. EP and Komis mines (closed) 14 1 20 #23 # 10 1 4# 24 # 9. Eldorado Verna, Ace-Fay, Nesbitt Labine (Eagle-Ace) 9. Corner Lake deposit 2 # 5 26 # 10. Tower East and Memorial deposits 17 # ###3 # 25 and Beaverlodge mines and Bolger open pit (closed) Lake Athabasca 21 3 2 10. Martin Lake mine (closed) 11. Birch Crossing deposits Fond du Lac # Black STONY Lake 11. Rix-Athabasca, Smitty, Leonard, Cinch and Cayzor 12. Jojay deposit RAPIDS MUDJATIK Athabasca mines (closed); St. Michael prospect 13. Star Lake mine (closed) # 27 53 12. Lorado mine (closed) 14. Jolu and Decade mines (closed) 13. Black Bay/Murmac Bay mine (closed) 15. Jasper mine (closed) Fond du Lac River 14.