Recording Industry Association of America, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yale-Classical Archives Corpus

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Music & Dance Department Faculty Publication Music & Dance Series 2016 The ale-CY lassical Archives Corpus Christopher William White University of Massachusetts Amherst Ian Quinn Yale University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/music_faculty_pubs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation White, Christopher William and Quinn, Ian, "The ale-CY lassical Archives Corpus" (2016). Empirical Musicology Review. 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/emr.v11i1.4958 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music & Dance at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music & Dance Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Empirical Musicology Review Vol. 11, No. 1, 2016 The Yale-Classical Archives Corpus CHRISTOPHER W M WHITE [1] The University of Massachusetts, Amherst IAN QUINN Yale University ABSTRACT: The Yale-Classical Archives Corpus (YCAC) contains harmonic and rhythmic information for a dataset of Western European Classical art music. This corpus is based on data from classicalarchives.com, a repository of thousands of user- generated MIDI representations of pieces from several periods of Western European music history. The YCAC makes available metadata for each MIDI file, as well as a list of pitch simultaneities (“salami slices”) in the MIDI file. Metadata include the piece’s -

Tamil Flac Songs Free Download Tamil Flac Songs Free Download

tamil flac songs free download Tamil flac songs free download. Get notified on all the latest Music, Movies and TV Shows. With a unique loyalty program, the Hungama rewards you for predefined action on our platform. Accumulated coins can be redeemed to, Hungama subscriptions. You can also login to Hungama Apps(Music & Movies) with your Hungama web credentials & redeem coins to download MP3/MP4 tracks. You need to be a registered user to enjoy the benefits of Rewards Program. You are not authorised arena user. Please subscribe to Arena to play this content. [Hi-Res Audio] 30+ Free HD Music Download Sites (2021) ► Read the definitive guide to hi-res audio (HD music, HRA): Where can you download free high-resolution files (24-bit FLAC, 384 kHz/ 32 bit, DSD, DXD, MQA, Multichannel)? Where to buy it? Where are hi-res audio streamings? See our top 10 and long hi-res download site list. ► What is high definition audio capability or it’s a gimmick? What is after hi-res? What's the highest sound quality? Discover greater details of high- definition musical formats, that, maybe, never heard before. The explanation is written by Yuri Korzunov, audio software developer with 20+ years of experience in signal processing. Keep reading. Table of content (click to show). Our Top 10 Hi-Res Audio Music Websites for Free Downloads Where can I download Hi Res music for free and paid music sites? High- resolution music free and paid download sites Big detailed list of free and paid download sites Download music free online resources (additional) Download music free online resources (additional) Download music and audio resources High resolution and audiophile streaming Why does Hi Res audio need? Digital recording issues Digital Signal Processing What is after hi-res sound? How many GB is 1000 songs? Myth #1. -

Reading Text 1

Reading text A You should spend about 20 minutes answering questions 1 to 10. India slowly gets ready for internet shopping Vipul Modi is a busy lawyer in India's financial capital Mumbai. Like many people, he uses the Internet to buy rail and airline tickets as well as pay his utility bills. Yet when it comes to buying other products online, the 44- year-old has doubts, particularly about the security of his bank account details and other (1) _______________ data. He says that online shopping is not something that people in India feel comfortable with because the (2) _________________of having to pay large sums of money, if your credit card is misused, is for the customer instead of the credit card companies. From books to groceries, Internet shopping has become popular in many Western countries for people with disposable income, busy lifestyles and unpredictable working hours. As Indian society changes, and perhaps as a (3) __________________ of the country's economic expansion, retailers are now looking to follow this shopping trend. Gift shop chain The Bombay Store recently became the latest outlet to launch an online facility, following in the footsteps of major retailers such as Big Bazaar, Pantaloons and shopping websites like www.rediff.com. Online shopping in India is just about to take off, according to Deepa Thomas, a senior manager at the Indian eBay online auction site, which has 2.5 million registered users in nearly 2,500 locations across the country. (4) ____________________, when it comes to buying products online there's still a fairly long way to go. -

Shopping for Classical Music Online

Shopping for Classical Music Online The primary focus of this article concerns finding online sources for purchase of so- called physical media—CDs, SACDs, Blu-Ray Audio discs—and not so much about digital downloads. For those readers interested in digital files and computer audio, I’ve included that as a separate discussion at the end. The ‘online’ part of this essay’s title is really an unnecessary add-on because when was the last time you’ve been in an actual store that sold classical CDs? Today everything is done online, so no need for the qualifier. The last time I was at Barnes and Nobles they only had 26 so-called classical selections which were mostly cheap compilations, crossover titles, and one CD by Bang Bang. I remember the days when I ran the classical section of a large record store and we had sixty titles in the bin just for Beethoven’s Ninth. But I’m not complaining since, in many ways, shopping is now easier both in terms of ordering from the comfort of your home at any time of the day or night, but also in being able sample recordings and find exactly what appeals to your own tastes. I’ve explored several online subscription streaming services, and I continue to buy CDs (and SACDs and DVDs) from a variety of sources which I’ll discuss here. The first question many ask when they see my wall-to-wall room with 6,000 CDs and separate storage room with 3,000 LPs is when am I going to get rid of all this museum stuff and go digital? Well, the answer is probably never. -

Marketing Plan

ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP An Allied Artists Int'l Company MARKETING & PROMOTION MARKETING PLAN: ROCKY KRAMER "FIRESTORM" Global Release Germany & Rest of Europe Digital: 3/5/2019 / Street 3/5/2019 North America & Rest of World Digital: 3/19/2019 / Street 3/19/2019 MASTER PROJECT AND MARKETING STRATEGY 1. PROJECT GOAL(S): The main goal is to establish "Firestorm" as an international release and to likewise establish Rocky Kramer's reputation in the USA and throughout the World as a force to be reckoned with in multiple genres, e.g. Heavy Metal, Rock 'n' Roll, Progressive Rock & Neo-Classical Metal, in particular. Servicing and exposure to this product should be geared toward social media, all major radio stations, college radio, university campuses, American and International music cable networks, big box retailers, etc. A Germany based advance release strategy is being employed to establish the Rocky Kramer name and bona fides within the "metal" market, prior to full international release.1 2. OBJECTIVES: Allied Artists Music Group ("AAMG"), in association with Rocky Kramer, will collaborate in an innovative and versatile marketing campaign introducing Rocky and The Rocky Kramer Band (Rocky, Alejandro Mercado, Michael Dwyer & 1 Rocky will begin the European promotional campaign / tour on March 5, 2019 with public appearances, interviews & live performances in Germany, branching out to the rest of Europe, before returning to the U.S. to kick off the global release on March 19, 2019. ALLIED ARTISTS INTERNATIONAL, INC. ALLIED ARTISTS MUSIC GROUP 655 N. Central Ave 17th Floor Glendale California 91203 455 Park Ave 9th Floor New York New York 10022 L.A. -

M10 Bluos Streaming Amplifier

M10 BluOS Streaming Amplifier The Audio World has shifted. The best quality of music available is now delivered over FEATURES & DETAILS the internet, not via disc. Not only does it sound better, but the entire catalog of recorded music is available at your fingertips; a great convenience. Curated playlists make music BluOS Streaming Amplifier selection and discovery easy and fun. Multi-room wireless audio multiplies the joy. HybridDigital nCore Amplifier With the NAD Masters M10 we combine all of this goodness with state-of-the-art Continuous Power: 100W into 8/4 Ohms amplification to make it an all-in-one solution that only needs speakers to transport you Dynamic Power: 160W into 8 Ohms to your favorite musical destination. 300W into 4 Ohms 32-BIT/384kHz ESS Sabre DAC BluOS MAKES THE M10 SOMETHING SPECIAL 1GHz ARM® CORTEX A9 Processor BluOS is the most advanced network streaming and multi-room operating system available. Part of a growing ecosystem of compatible products, BluOS tightly integrates Dirac Live Room Correction* hardware and software for an unbeatable user experience. The only wireless High Color LCD display Resolution multi-room system available today, BluOS supports the new standard for Supports Amazon Alexa & Google Assistant High Res streaming, Master Quality Authenticated (MQA). BluOS also supports over 15 Voice Control Skills free and paid subscription services as well as supporting locally stored music libraries. AirPlay 2 Integration* Adding additional rooms is easy and affordable using Bluesound all-in-one speakers, or Supports Siri Voice Assistant via AirPlay 2 you can add premium components from NAD, DALI, and others to provide amazing sound throughout your home. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 24/Tuesday, February 5, 2019/Proposed Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 24 / Tuesday, February 5, 2019 / Proposed Rules 1661 Insurance Corporation Improvement Act Dated at Washington, DC, on December 18, statutory deadlines set forth in the of 1991, 12 U.S.C. 1828(o), prescribes 2018. Music Modernization Act, no further standards for real estate lending to be By order of the Board of Directors. extensions of time will be granted in used by FDIC-supervised institutions in Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. this rulemaking. adopting internal real estate lending Valerie Best, ADDRESSES: For reasons of government policies. For purposes of this subpart, Assistant Executive Secretary. efficiency, the Copyright Office is using the term ‘‘FDIC-supervised institution’’ [FR Doc. 2018–28084 Filed 2–4–19; 8:45 am] the regulations.gov system for the means any insured depository BILLING CODE 6714–01–P submission and posting of public institution for which the Federal comments in this proceeding. All Deposit Insurance Corporation is the comments are therefore to be submitted appropriate Federal banking agency LIBRARY OF CONGRESS electronically through regulations.gov. pursuant to section 3(q) of the Federal Specific instructions for submitting Deposit Insurance Act, 12 U.S.C. Copyright Office comments are available on the 1813(q). Copyright Office’s website at https:// ■ 3. Amend § 365.2 by revising 37 CFR Part 201 www.copyright.gov/rulemaking/ paragraphs (a), (b)(1)(iii), (2)(iii) and pre1972-soundrecordings- (iv), and (c) to read as follows: [Docket No. 2018–8] noncommercial/. If electronic submission of comments is not feasible Noncommercial Use of Pre-1972 Sound § 365.2 Real estate lending standards. -

IFPI Digital Music Report 2013 Engine of a Digital World

IFPI Digital Music Report 2013 Engine of a digital world 9 IN 10 MOST LIKED PEOPLE ON FACEBOOK ARE ARTISTS 9 IN 10 OF THE MOST WATCHED VIDEOS ON YOUTUBE ARE MUSIC 7 IN 10 MOST FOLLOWED TWITTER USERS ARE ARTISTS Deezer4artists-HD_acl.pdf 1 26/02/13 17:37 2 Contents Introduction 4-5 Music is an engine of the digital world 22-23 g Plácido Domingo, chairman, IFPI g Fuelling digital engagement g Frances Moore, chief executive, IFPI g Fuelling hardware adoption g Driving the live entertainment industry An industry on the road to recovery: g Attracting customers, driving profits Facts and figures 6-10 Going global: the promise of emerging markets 24-27 Global best sellers 11-13 g Brazil: A market set to surge g Top selling albums g Russia: Hurdles to growth can be overcome g Top selling singles g India: Nearing an all-time high g Strong local repertoire sales g Strong market potential in The Netherlands Digital music fuels innovation 14-17 Engaging with online intermediaries 28-30 g Download stores receive a boost from the cloud g Advertising: tackling a major source of funding for music piracy g Subscription services come of age g Search engines – a vital role to play g Subscription transforming the industry’s business model g Further ISP cooperation needed g Growth for music video g Payment providers step up action on illegal sites g The next generation radio experience g Europe: Licensing helps digital consumers Disrupting illegal online businesses 31 The art of digital marketing 18-21 g Disrupting unlicensed cyberlockers g Reducing pre-release leaks g One Direction mobilise an online army g Dance label harnesses social media Digital music services worldwide 32-34 g A personal video for every fan: Linkin Park g Taking classical digital Cover photo credits: Michel Teló. -

Internet Infrastructure Review Vol.30

3. Technology Trends High-Resolution Audio and Steps Toward Implementing DSD Streaming Although many people enjoy listening to music on portable audio players or smartphones on a daily basis now, there perhaps aren’t so many who are interested in its audio quality. However, it may have occurred to people that “high-resolution audio” seems to be popular now, after finding articles about it in newspapers and magazines, or seeing dedicated space for high-resolution audio in large electronics retail stores over the past few years. “Hi-Res Audio” is a term used to indicate high resolution music content and its compatible audio devices with sound quality in excess of CD (Compact Disc) and DAT (Digital Audio Tape). Here we will discuss what exactly changes when the resolution is increased. ■ What’s Hi-Res Audio? What’s DSD? When converting audio waveforms to digital signals in the PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) format widely used for digital audio, the analog signal is sampled at set intervals (from tens of thousands of cycles per second to hundreds of thousands of cycles per second), and their size is expressed as digital code in certain digits (quantization bits number). That means you could regard the analog signal as being converted to staircase waveform information as shown in the Figure 1. Based on the staircase waveform on the left, we can see at a glance that the staircase waveform on the right with finer time axis and step size is closest to the original analog signal. However, it is also clear that the top staircase waveform with the finer time axis only, as well as the bottom staircase waveform with the finer step size only, are closer to the original analog signal than the staircase waveform on the left. -

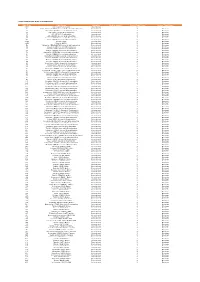

Codes Used in D&M

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

Computer Audio Demystified 2.0 December 2012

Computer Audio Demystified 2.0 December 2012 What is Computer Audio? From iTunes®, streaming music and podcasts to watching YouTube videos, TV shows or movies, today’s computers are the hub that connects people to a vast universe of digital entertainment content. Computer audio playback can be as simple as playing those files or streams on a portable media player like an iPod®, iPad®, or a smart phone device such as the iPhone® or an Android™ phone. Or it can be as sophisticated as a component-based home entertainment system using a high-end Digital-Audio Converter (aka DAC). In this brave new frontier of computer-based digital audio, the current reality is that a lossless 16-bit/44.1kHz digital music file can sound far better than the CD it was ripped from when each is played in real time, and a high-resolution 24-bit/88.2kHz digital music file can truly compete with vinyl’s sonic beauty without our beloved vinyl’s flaws. Notice there is a bunch of “cans” in the line above. Great audio is possible in this new computer audio world, but it is not automatic. Just as adjusting the stylus rake angle properly is critical to getting the best performance from a turntable, knowledge is required to optimize the hardware and software that will define the performance boundaries of your computer audio experience. AudioQuest’s Computer Audio Demystified is a guide created to dispel some of the myths about computer audio and establish some “best practices” in streaming, acquiring and managing digital music. -

Billboard Magazine

Pop's princess takes country's newbie under her wing as part of this season's live music mash -up, May 31, 2014 1billboard.com a girl -powered punch completewith talk of, yep, who gets to wear the transparent skirt So 99U 8.99C,, UK £5.50 SAMSUNG THE NEXT BIG THING IN MUSIC 200+ Ad Free* Customized MINI I LK Stations Radio For You Powered by: Q SLACKER With more than 200 stations and a catalog of over 13 million songs, listen to your favorite songs with no interruption from ads. GET IT ON 0)*.Google play *For a limited time 2014 Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC. Samsung and Milk Music are both trademarks of Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. Appearance of device may vary. Device screen imagessimulated. Other company names, product names and marks mentioned herein are the property of their respective owners and may be trademarks or registered trademarks. Contents ON THE COVER Katy Perry and Kacey Musgraves photographed by Lauren Dukoff on April 17 at Sony Pictures in Culver City. For an exclusive interview and behind-the-scenes video, go to Billboard.com or Billboard.com/ipad. THIS WEEK Special Double Issue Volume 126 / No. 18 TO OUR READERS Billboard will publish its next issue on June 7. Please check Billboard.biz for 24-7 business coverage. Kesha photographed by Austin Hargrave on May 18 at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. FEATURES TOPLINE MUSIC 30 Kacey Musgraves and Katy 5 Can anything stop the rise of 47 Robyn and Royksopp, Perry What’s expected when Spotify? (Yes, actually.) Christina Perri, Deniro Farrar 16 a country ingenue and a Chart Movers Latin’s 50 Reviews Coldplay, pop superstar meet up on pop trouble, Disclosure John Fullbright, Quirke 40 “ getting ready for tour? Fun and profits.