Fictional Uncertainty in Modern Persian Literature: Polyphony, Becoming, and Ambiguity in Shahriar Mandanipour's Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File (Pdf; 3Mb)

Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CINEMACINEMA ● IIndianndian camera,camera, IranianIranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd dramaticdramatic rootsroots ofof thethe IranianIranian NewNew WaveWave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran inin ‘Film‘Film Farsi’Farsi’ popularpopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: socio-politicalsocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed asas villagevillage foolfool ● TThehe nnoiroir worldworld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ofof IranianIranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred Defence’Defence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar Farhadi’sFarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew diasporicdiasporic visionsvisions ofof IranIran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 15 - Number 2 February – March 2019 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: IIRANIANRANIAN CCINEMAINEMA ● IIndianndian ccamera,amera, IIranianranian heartheart ● TThehe lliteraryiterary aandnd ddramaticramatic rootsroots ooff thethe IIranianranian NNewew WWaveave ● DDystopicystopic TTehranehran iinn ‘Film-Farsi’‘Film-Farsi’ ppopularopular ccinemainema ● PParvizarviz SSayyad:ayyad: ssocio-politicalocio-political commentatorcommentator dresseddressed aass vvillageillage ffoolool ● TThehe nnoiroir wworldorld ooff MMasudasud KKimiaiimiai ● TThehe rresurgenceesurgence ooff IIranianranian ‘Sacred‘Sacred DDefence’efence’ CinemaCinema ● AAsgharsghar FFarhadi’sarhadi’s ccinemainema ● NNewew ddiasporiciasporic visionsvisions ooff IIranran ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents -

Persian 1103 Course Change.Pdf

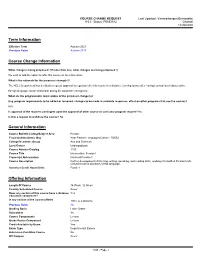

COURSE CHANGE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 1103 - Status: PENDING Chantal 11/20/2020 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2021 Previous Value Autumn 2015 Course Change Information What change is being proposed? (If more than one, what changes are being proposed?) We wish to add the option to offer this course as an online class. What is the rationale for the proposed change(s)? The NELC Department has decided to request approval to regularly offer this course in a distance learning format after having learned much about online foreign language course instruction during the pandemic emergency. What are the programmatic implications of the proposed change(s)? (e.g. program requirements to be added or removed, changes to be made in available resources, effect on other programs that use the course)? N/A Is approval of the requrest contingent upon the approval of other course or curricular program request? No Is this a request to withdraw the course? No General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Persian Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Near Eastern Languages/Culture - D0554 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Undergraduate Course Number/Catalog 1103 Course Title Intermediate Persian I Transcript Abbreviation Intermed Persian 1 Course Description Further development of listening, writing, speaking, and reading skills; reading of simplified Persian texts. Closed to native speakers of this language. Semester Credit Hours/Units Fixed: 4 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 12 Week Flexibly -

The Devils' Dance

THE DEVILS’ DANCE TRANSLATED BY THE DEVILS’ DANCE HAMID ISMAILOV DONALD RAYFIELD TILTED AXIS PRESS POEMS TRANSLATED BY JOHN FARNDON The Devils’ Dance جينلر بازمي The jinn (often spelled djinn) are demonic creatures (the word means ‘hidden from the senses’), imagined by the Arabs to exist long before the emergence of Islam, as a supernatural pre-human race which still interferes with, and sometimes destroys human lives, although magicians and fortunate adventurers, such as Aladdin, may be able to control them. Together with angels and humans, the jinn are the sapient creatures of the world. The jinn entered Iranian mythology (they may even stem from Old Iranian jaini, wicked female demons, or Aramaic ginaye, who were degraded pagan gods). In any case, the jinn enthralled Uzbek imagination. In the 1930s, Stalin’s secret police, inveigling, torturing and then executing Uzbekistan’s writers and scholars, seemed to their victims to be the latest incarnation of the jinn. The word bazm, however, has different origins: an old Iranian word, found in pre-Islamic Manichaean texts, and even in what little we know of the language of the Parthians, it originally meant ‘a meal’. Then it expanded to ‘festivities’, and now, in Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan, it implies a riotous party with food, drink, song, poetry and, above all, dance, as unfettered and enjoyable as Islam permits. I buried inside me the spark of love, Deep in the canyons of my brain. Yet the spark burned fiercely on And inflicted endless pain. When I heard ‘Be happy’ in calls to prayer It struck me as an evil lure. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

The La Trobe Journal No. 91 June 2013 Endnotes Notes On

Endnotes NB: ‘Scollay’ refers to Susan Scollay, ed., Love and Devotion: from Persia and beyond, Melbourne: Macmillan Art Publishing in association with the State Library of Victoria and the Bodleian Library, 2012; reprinted with new covers, Oxford: The Bodleian Library, 2012. Melville, The ‘Arts of the Book’ and the Diffusion of Persian Culture 1 This article is a revised version of the text of the ‘Keynote’ lecture delivered in Melbourne on 12 April 2012 to mark the opening of the conference Love and Devotion: Persian cultural crossroads. It is obviously not possible to reproduce the high level of illustrations that accompanied the lecture; instead I have supplied references to where most of them can be seen. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all those at the State Library of Victoria who worked so hard to make the conference such a success, and for their warmth and hospitality that made our visit to Melbourne an unrivalled pleasure. A particular thanks to Shane Carmody, Robert Heather and Anna Welch. 2 The exhibition Love and Devotion: from Persia and beyond was held in Melbourne from 9 March to 1 July 2012 with a second showing in Oxford from 29 November 2012 to 28 April 2013. It was on display at Oxford at the time of writing. 3 Scollay. 4 For a recent survey of the issues at stake, see Abbas Amanat and Farzin Vejdani, eds., Iran Facing Others: identity boundaries in a historical perspective, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; the series of lectures on the Idea of Iran, supported by the Soudavar Memorial Foundation, has now spawned five volumes, edited by Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis and Sarah Stewart, vols. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

The Danger of a Single Story‟: Reading (More Than) Lolita in Tehran Saiyma Aslam1

Kashmir Journal of Languager Research, Vol. 23 No. 1 (2020) 79 „The Danger of a Single Story‟: Reading (more than) Lolita in Tehran Saiyma Aslam1 Abstract „The danger of a single story‟ is incalculable especially when it shapes judgments in support of Western imperial aggression in the name of War on Terror. Following Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie‟s stand on discursive dangers of a single story, Peter McLaren‟s take on the need of critical pedagogy to study who benefits from popularization of certain accounts and why and Hilde Lindemann Nelson‟s research on developing “counterstory” to offset the negative image an oppressive story conveys, I argue that a contrapuntal study of Azar Nafisi‟s Reading Lolita in Tehran is needed to expose its reductive, decontextualized and neo-orientalist details about Iranian women, culture and politics. For that, I draw comparisons with Fatemeh Keshavarz‟s Jasmine and stars: Reading more than Lolita in Tehran (2007), Shirin Ebadi‟s Iran awakening: A memoir of revolution and hope (2006) and Azadeh Moaveni‟s Lipstick jihad: A memoir of growing up Iranian in America and American in Iran (2005). This article argues for a critical dialogue between memoirs and their social and political settings to offset the negative implications of reductive and decontextualized accounts and encourage greater circulation of multiple perspectives on any situation. Keywords: post 9/11, counter story, critical pedagogy, neo-orientalism, memoir. 1. Introduction The Muslim woman is a “semiotic subject” and an unfixed signifier that has been “produced and reproduced” in orientalist and neo-orientalist discourses to further the interests of the West (Zayzafoon, 2005, p.2).2 Never has this had such an unsettling repercussions than in the case of new positioning(s) she has received through a double bind: how our elite group of neo-orientalists/neo-comprador intelligencia ties horns with the US liberal, neo conservative agenda tuned more 1 Assistant Professor, Department of English, IIU, Islamabad. -

The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: a Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran

The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: A Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran by Samad Josef Alavi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Shahwali Ahmadi, Chair Professor Muhammad Siddiq Professor Robert Kaufman Fall 2013 Abstract The Poetics of Commitment in Modern Persian: A Case of Three Revolutionary Poets in Iran by Samad Josef Alavi Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shahwali Ahmadi, Chair Modern Persian literary histories generally characterize the decades leading up to the Iranian Revolution of 1979 as a single episode of accumulating political anxieties in Persian poetics, as in other areas of cultural production. According to the dominant literary-historical narrative, calls for “committed poetry” (she‘r-e mota‘ahhed) grew louder over the course of the radical 1970s, crescendoed with the monarch’s ouster, and then faded shortly thereafter as the consolidation of the Islamic Republic shattered any hopes among the once-influential Iranian Left for a secular, socio-economically equitable political order. Such a narrative has proven useful for locating general trends in poetic discourses of the last five decades, but it does not account for the complex and often divergent ways in which poets and critics have reconciled their political and aesthetic commitments. This dissertation begins with the historical assumption that in Iran a question of how poetry must serve society and vice versa did in fact acquire a heightened sense of urgency sometime during the ideologically-charged years surrounding the revolution. -

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY for IRANIAN STUDIES انجمن بین املللی ایران شناسی ISIS Newsletter Volume 37, Number 1 May 2016

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR IRANIAN STUDIES انجمن بین املللی ایران شناسی www.societyforiranianstudies.org ISIS Newsletter Volume 37, Number 1 May 2016 PRESIDENT’S NOTE Although the festivities of Nowruz 1395 have come to an end, nevertheless I would like to take this opportunity to wish all members of our society a very happy and prosperous 1395! Since the publication of the last issue of the newsletter, the online election for the new president was held and my good friend Touraj Daryaee now stands as the President-Elect. Also, Elena Andreeva and Afshin Marashi joined the Council. I am very grateful to the collective team of colleagues on the board for their commitment to our society. Preparation for the forthcoming Eleventh Biennial Conference of The International Society for Iranian Studies is underway and the head of the Conference Committee, Florian Schwarz, and Programme Committee Chair Camron Amin together with their colleagues on both committees are doing their best to make the Eleventh Biennial another successful conference, this time in Vienna. I look forward to seeing all our members at the beginning of August in Vienna. Touraj Atabaki Amsterdam, April 2016 The International Society for Iranian Studies Founded in 1967 ISIS 2016 OFFICERS ISIS Newsletter Volume 37, Number 1 May 2016 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The second reason is that some years ago when we were on summer vacation 2016 AFRO-IRANIANS: in Iran with family and friends, I saw an Afro-Iranian man for the first time. We went to a football match between Bargh Shiraz FC and Aluminium Hormozgan FC. The TOURAJ ATABAKI AN ELEMENT IN A MOSAIC PRESIDENT man was the fan leader of the Hormozgan team and I was quickly drawn to the way the fans joyfully and rhythmically chanted for their team. -

Focalization and Knowledge Dissemination in the Story of “Khosrow and Shirin” in Shahnameh

Journal of Research Literary Studies (Peer-reviewed Journal) Vol 52, No. 1 (2019) 11 Focalization and Knowledge Dissemination in the Story of “Khosrow and Shirin” in Shahnameh Dr. Najmeh Hosseini Sarvari1*, Dr. Mahmood Modabberi2, Mohammad Jafari3 1 Associate Professor, Department of Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran. 2 Professor, Department of Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran. 3Ph.D.Candidate in Persian Language and Literature, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran. (Received: December 13, 2018 Accepted: December 4, 2019) Extended Abstract 1. Introduction Focalization is a way of communicating or acquiring knowledge (information) in narratives. Studying ways of focalization in narrative means understanding and analyzing how the narrator distributes information. In different scenes of the story, the narrator, depending on the reaction he expects from the reader, gives the reader more information, equal to or less than the characters in the story. If the reader's knowledge is more than personalities, the result is suspense and if the reader's knowledge is equal to the characters, his reaction to the events and actions of the story’s characters is curiosity. And if the reader knows less about the story's characters than about the events, he is surprised. The purpose of this study is to investigate the ways of information distribution in the Shahnameh narrative of Khosrow and Shirin's story. It tries to explain methods and techniques of information distribution in the story and its impact on the reader. -

KHERAD-DISSERTATION-2013.Pdf

Copyright by Nastaran Narges Kherad 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Nastaran Narges Kherad Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY Committee: M.R. Ghanoonparvar, Supervisor Kamran Aghaie Kristen Brustad Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Faegheh Shirazi RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY by Nastaran Narges Kherad, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication Dedicated to my son, Manai Kherad-Aminpour, the joy of my life. May you grow with a passion for literature and poetry! And may you face life with an adventurous spirit and understanding of the diversity and complexity of humankind! Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation could not have been possible without the ongoing support of my committee members. First and for most, I am grateful to Professor Ghanoonparvar, who believed in this project from the very beginning and encouraged me at every step of the way. I thank him for giving his time so generously whenever I needed and for reading, editing, and commenting on this dissertation, and also for sharing his tremendous knowledge of Persian literature. I am thankful to have the pleasure of knowing and working with Professor Kamaran Aghaei, whose seminars on religion I cherished the most. -

Forugh Farrojzad Y Alejandra Pizarnik: Obra Literaria Y Contexto Social

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA ESPAÑOLA FORUGH FARROJZAD Y ALEJANDRA PIZARNIK: OBRA LITERARIA Y CONTEXTO SOCIAL. ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: Nafiseh Zifan Dirigida por: Dra. Dña. Selena Millares Martín Madrid 2019 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA ESPAÑOLA FORUGH FARROJZAD Y ALEJANDRA PIZARNIK: OBRA LITERARIA Y CONTEXTO SOCIAL. ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: Nafiseh Zifan Dirigida por: Dra. Dña. Selena Millares Martín Madrid 2019 A mis padres, me gustaría agradecérles de todo corazón, pero para ustedes, mi querida esperanza, mi corazón no tiene fondo. i AGRADECIMIENTOS A Dios, el ser omnipotente que me ha dado la vida y me lleva cada día de las manos, por las grandes oportunidades que me da irradiando. A la admirable profesora, Dra. Selena Millares Martín, por su confianza en mi trabajo, su sabia dirección, sus valiosas aportaciones y su apoyo constante, así como por la amabilidad y el cariño que ha mostrado durante esta larga andadura por los caminos del conocimiento y de la complicidad intelectual. A mis padres y hermanos, por su colaboración y compasión, y su apoyo incondicional en cumplir con excelencia el desarrollo de esta tesis. Espero que este diminuto trabajo pueda agradecer una pequeña parte de sus esfuerzos. A mi amiga Karina, por su compañía y atención en este trabajo. A todas aquellas personas que de una u otra forma estuvieron relacionadas y me apoyaron de manera desinteresada. A todos ellos muchas gracias. ii ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 1 I. LA POESÍA A ESCALA GLOBAL: SITUACIÓN SOCIAL E HISTÓRICA DE LAS POETAS CONTEMPORÁNEAS 1.