(Q. 3:64): the Ten Commandments and the Qur'an

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths

Messiah University Mosaic Bible & Religion Educator Scholarship Biblical and Religious Studies 1-1-2011 The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths Larry Poston Messiah College, [email protected] Linda Poston Messiah College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/brs_ed Part of the Library and Information Science Commons, and the Religion Commons Permanent URL: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/brs_ed/6 Recommended Citation Poston, Larry and Poston, Linda, "The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths" (2011). Bible & Religion Educator Scholarship. 6. https://mosaic.messiah.edu/brs_ed/6 Sharpening Intellect | Deepening Christian Faith | Inspiring Action Messiah University is a Christian university of the liberal and applied arts and sciences. Our mission is to educate men and women toward maturity of intellect, character and Christian faith in preparation for lives of service, leadership and reconciliation in church and society. www.Messiah.edu One University Ave. | Mechanicsburg PA 17055 Running head: THE WORDPoston AND and WORDS Poston: The Word and Words in Abrahamic Faiths “The Word and Words in the Abrahamic Faiths” Linda and Larry Poston Nyack College Published by Digital Commons @ Kent State University Libraries, 2011 1 Advances in the Study of Information and Religion, Vol. 1 [2011], Art. 2 THE WORD AND WORDS Abstract Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are “word-based” faiths. All three are derived from texts believed to be revealed by God Himself. Orthodox Judaism claims that God has said everything that needs to be said to humankind—all that remains is to interpret it generation by generation. Historic Christianity roots itself in “God-breathed scriptures” that are “useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness.” Islam’s Qur’an is held to be a perfect reflection of the ‘Umm al-Kitab – the “mother of Books” that exists with Allah Himself. -

Fisher, Memories of The

Memories of the Ark: Texts, Objects, and the Construction of the Biblical Past By Daniel Shalom Fisher A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ronald Hendel, Chair Professor Robert Alter Professor Benjamin Porter Professor Daniel Boyarin Professor Ann Swidler Summer 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Daniel Shalom Fisher, All Rights Reserved. 1 Abstract Memories of the Ark: Texts, Objects, and the Construction of the Biblical Past by Daniel Shalom Fisher Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Ronald Hendel, Chair This dissertation constructs a cultural biography of the Ark of the Covenant, exploring through it the close, but often complicated, relationships that have existed between objects and collective memory in Biblical and ancient Jewish societies. The project considers the different ways in which Biblical writers and interpreters have remembered the Ark as a “real thing,” forming it, mobilizing it, and making meaning with it—largely in its absence after its likely loss in the 6th century BCE. From Exodus to Chronicles and in works of biblical interpretation through the Mishnah, this project explores how these writers reimagine the Ark to craft visions for their people’s future through their people’s past. The project is structured around five interrelated case studies from the Ark’s mnemohistory, considering different dimensions of cultural memory’s entanglement in material culture. Each case study draws upon and enriches text-, source-, and redaction-critical approaches, investigating the growth and reshaping of biblical writings as creative memory work. -

Exodus 20: 1-17 March 7, 2021 – Lent 3 Stacy Carlson Mystery And

Exodus 20: 1-17 March 7, 2021 – Lent 3 Stacy Carlson Mystery and Meaning in Stone Good morning everyone. No matter what tradition we come from, most of us probably know this passage from Exodus, at least as the headline we call the Ten Commandments. These are ten rules or laws for how we should behave. They seem especially important during Lent, don't they? Yes, but perhaps not in the way we might think, because when a story is familiar, sometimes it doesn’t seem as meaningful the second and third time around as it was the first. We think we have learned all there is to know. So it might be with the Ten Commandments. But today, let’s try to look at them differently. One way is to think more about the stone tablets. Were they gray? Brown? Were they red clay? How much did they weigh? Did God chisel them letter by letter, or in a big flash all at once? Do we know if the commandments were divided equally – five and five -- between the tablets? And don't we wonder what the Israelites thought when Moses came down carrying stone tablets from a mountain shrouded in clouds, but also bursting with thunder and fire? Even if we knew the answers to all those questions, what new lesson can we learn today? I believe there is still mystery and meaning in these two stone tablets. What if we imagine the world after the pandemic? Imagine we're gathered outside a Metro station in DC. Let's say Dupont Circle. -

Exodus 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Exodus 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The Hebrew title of this book (we'elleh shemot) originated from the ancient practice of naming a Bible book after its first word or words. "Now these are the names of" is the translation of the first two Hebrew words. "The Hebrew title of the Book of Exodus, therefore, was to remind us that Exodus is the sequel to Genesis and that one of its purposes is to continue the history of God's people as well as elaborate further on the great themes so nobly introduced in Genesis."1 Exodus cannot stand alone, in the sense that the book would not make much sense without Genesis. The very first word of the book, translated "now," is a conjunction that means "and." The English title "Exodus" is a transliteration of the Greek word exodus, from the Septuagint translation, meaning "exit," "way out," or "departure." The Septuagint translators gave the book this title because of the major event in it, namely, the Israelites' departure from Egypt. "The exodus is the most significant historical and theological event of the Old Testament …"2 DATE AND WRITER Moses, who lived from about 1525 to 1405 B.C., wrote Exodus (17:14; 24:4; 34:4, 27-29). He could have written it, under the inspiration of the 1Ronald Youngblood, Exodus, pp. 9-10. 2Eugene H. Merrill, Kingdom of Priests, p. 57. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. Constable www.soniclight.com 2 Dr. Constable's Notes on Exodus 2021 Edition Holy Spirit, any time after the events recorded (after about 1444 B.C.). -

Joshua 5:13-6:27 INTRODUCTION: Jericho Was a City Near the Dead Sea and the Jordan River

Joshua and the Conquest of Jericho TEXT: Joshua 5:13-6:27 INTRODUCTION: Jericho was a city near the Dead Sea and the Jordan River. As the Israelites crossed over the Jordan River, they came first to the city of Jericho. They would not be able to go any further into the Promised Land unless they went through Jericho. They knew. God knew it. Jericho would be a city specifically cursed by the Lord. The Jews were to conquer the city, but they were not to take any of the possessions of the city for themselves. However, the city had huge walls. The border of the city was actually two huge walls, one inside the other. The walls were so thick that six horses and a chariot could travel along the top of the walls. Houses were built into and between the walls, and many people, such as Rahab the harlot, lived in these houses. God commanded Joshua and Israel conquer this city. Bear in mind, they had no army. They had been in the wilderness for forty years. They simply had God’s command to take the city, and God gave it to them in a miraculous way. How could an untrained band of wilderness wandering travelers defeat a well-armed army in a fortified city? It happened because…. I. THEY HAD FAITH IN GOD’S COMMANDER A. The people knew God put Joshua in charge – They had all seen when God met with Moses and Joshua and turned over the leadership of the nation from Moses to Joshua. -

Why Did Moses Break the Tablets (Ekev)

Thu 6 Aug 2020 / 16 Av 5780 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Torah discussion on Ekev Why Did Moses Break the Tablets? Introduction In this week's portion, Ekev, Moses recounts to the Israelites how he broke the first set of tablets of the Law once he saw that they had engaged in idolatry by building and worshiping a golden calf: And I saw, and behold, you had sinned against the Lord, your God. You had made yourselves a molten calf. You had deviated quickly from the way which the Lord had commanded you. So I gripped the two tablets, flung them away with both my hands, and smashed them before your eyes. [Deut. 9:16-17] This parallels the account in Exodus: As soon as Moses came near the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, he became enraged; and he hurled the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain. [Exodus 32:19] Why did he do that? What purpose did it accomplish? -Wasn’t it an affront to God, since the tablets were holy? -Didn't it shatter the authority of the very commandments that told the Israelites not to worship idols? -Was it just a spontaneous reaction, a public display of anger, a temper tantrum? Did Moses just forget himself? -Why didn’t he just return them to God, or at least get God’s approval before smashing them? Yet he was not admonished! Six explanations in the Sources 1-Because God told him to do it 1 The Talmud reports that four prominent rabbis said that God told Moses to break the tablets. -

THE ARK of the COVENANT the Ark of the Testimony Was the Chief Piece of Furniture in the Tabernacle

THE ARK OF THE COVENANT The Ark of the testimony was the chief piece of furniture in the tabernacle. It was a chest. In Hebrew the word for this “Ark” was a different word from the one for Noah’s Ark, and from the basket where Moses was placed as a baby in the Nile. It was 2½ x 1½ x 1½ cubits, made of acacia wood and overlaid inside and outside with pure gold. A rim of gold encircled it at the top. On each side at the bottom there were two golden rings. Poles of acacia wood covered with gold were put through these rings so that Levites of the family of Kohath could carry it. On solemn occasions priests carried it. It was covered by a lid of solid gold, called the “mercy seat” or “the atonement cover:” Two cherubim of gold stood on the cover, of one piece with the mercy seat, one on each side, spreading their wings so as to overshadow it. They were symbols of the presence of the Lord. There the LORD dwelt in the midst of His people. The Ark was made especially to hold the two tablets of the Law. God Himself had written His Ten Commandments on tablets of stone. The popular custom of calling commandments I-III “the first table” and commandments IV-X “the second table” is mistaken. When people of old made a covenant, as when people sign an important document today, each party kept a copy. There were two full sets of the Ten Commandments, God’s copy, and the people’s copy, and both were kept in the Ark of the Covenant. -

An Order for the Worship of God Entrance Gathering Of

AN ORDER FOR THE WORSHIP OF GOD ANTHEM Rise, Shine! Wood For you alone are the Holy One, Chancel Choir you alone are the Lord, ENTRANCE you alone are the Most High, * GOSPEL LESSON Matthew 17:1-9 Jesus Christ, GATHERING OF THE CHURCH Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter and James and his brother with the Holy Spirit, John and led them up a high mountain, by themselves. And he was PRELUDE Fairest Lord Jesus McDonald in the glory of God the Father. Amen. transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his * GREETING adapted from Psalm 99 clothes became dazzling white. Suddenly there appeared to them * THE GLORIA PARTI Leader: The Lord reigns; let the peoples tremble! Moses and Elijah, talking with him. Then Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, Glory be to the Father People: The Lord sits enthroned; let the earth quake! it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will make three dwellings And to the Son and to the Holy Ghost; Leader: The Lord is great and exalted over all the peoples. Let us here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” While he was As it was in the beginning, praise your holy and wondrous name! still speaking, suddenly a bright cloud overshadowed them, and from Is now and ever shall be, People: God is a mighty Ruler, establishing equity, executing the cloud a voice said, “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am World without end. Amen. Amen. justice and righteousness. -

Kebra Nagast

TheQueenofShebaand HerOnlySonMenyelek (KëbraNagast) translatedby SirE.A.WallisBudge InparenthesesPublications EthiopianSeries Cambridge,Ontario2000 Preface ThisvolumecontainsacompleteEnglishtranslationofthe famousEthiopianwork,“TheKëbraNagast,”i.e.the“Gloryof theKings[ofEthiopia].”Thisworkhasbeenheldinpeculiar honourinAbyssiniaforseveralcenturies,andthroughoutthat countryithasbeen,andstillis,veneratedbythepeopleas containingthefinalproofoftheirdescentfromtheHebrew Patriarchs,andofthekinshipoftheirkingsoftheSolomonic linewithChrist,theSonofGod.Theimportanceofthebook, bothforthekingsandthepeopleofAbyssinia,isclearlyshown bytheletterthatKingJohnofEthiopiawrotetothelateLord GranvilleinAugust,1872.Thekingsays:“Thereisabook called’KiveraNegust’whichcontainstheLawofthewholeof Ethiopia,andthenamesoftheShûms[i.e.Chiefs],and Churches,andProvincesareinthisbook.IÊprayyoufindout whohasgotthisbook,andsendittome,forinmycountrymy peoplewillnotobeymyorderswithoutit.”Thefirstsummary ofthecontentsofthe KëbraNagast waspublishedbyBruceas farbackas1813,butlittleinterestwasrousedbyhissomewhat baldprécis.And,inspiteofthelaboursofPrætorius,Bezold, andHuguesleRoux,thecontentsoftheworkarestill practicallyunknowntothegeneralreaderinEngland.Itis hopedthatthetranslationgiveninthefollowingpageswillbe ii Preface ofusetothosewhohavenotthetimeoropportunityfor perusingtheEthiopicoriginal. TheKëbraNagast isagreatstorehouseoflegendsand traditions,somehistoricalandsomeofapurelyfolk-lore character,derivedfromtheOldTestamentandthelater Rabbinicwritings,andfromEgyptian(bothpaganand -

Studies in the Life of Solomon ∙ Lesson 1 ∙ Text: 1 Kings 1; 2 Chronicles

Studies in the Life of Solomon ∙ Lesson 1 ∙ Text: 1 Kings 1; 2 Chronicles Introduction: There are many reasons one could give for choosing to study the life of Solomon. I began with the thought of using this study as a follow-up to our study, The Life of King David. Secondly, we have always greatly benefited from our studies of biblical characters (Daniel, Esther, Ruth, Elijah to name some). But perhaps what drew me most to Solomon was my reading of a study by Dr. Philip Graham Ryken on the life of Solomon, which we will use to guide us in our study along with Tyndale’s Cornerstone Biblical Commentary by William Barnes, The Expositors Bible Commentary by R. D. Patterson, and Focus on the Bible series by Dr. Dale Ralph Davis. It should be noted that we will not be studying the entire book of 1 Kings, only the life of Solomon, which is covered in the first 11 chapters of 1 Kings. It should also be noted that the book of 2 Chronicles will be used as an additional source for our study as it provides insights not provided by the writers of 1 Kings. One final note, by William Barnes regarding the authorship of 1 Kings: “As is the case with many of the books of the Old Testament, the author (or authors) of the books of 1-2 Kings is unknown. The title “Kings” clearly has to do with the content of Kings, not with the identity of the author. This is also the case, for example, with 1-2 Samuel, in which Samuel the prophet himself is last mentioned in 1 Samuel 28, when he was already dead and called up from the grave!. -

A Political Interpretation of Exodus 17:8-16 and Related Texts

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 70 Issue 4 Symposium on Ancient Law, Economics & Society Part I: The Development of Law in Classical and Early Medieval Europe / Article 17 Symposium on Ancient Law, Economics & Society Part I: The Development of Law in the Ancient Near East June 1995 J as Constitutionalist: A Political Interpretation of Exodus 17:8-16 and Related Texts Geoffrey P. Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Geoffrey P. Miller, J as Constitutionalist: A Political Interpretation of Exodus 17:8-16 and Related Texts, 70 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 1829 (1995). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol70/iss4/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. J AS CONSTITUTIONALIST: A POLITICAL INTERPRETATION OF EXODUS 17:8-16 AND RELATED TEXTS GEOFFREY P. MILLER* In this Article, I argue that the pericope in Exodus 17:8-16, which recounts a wilderness battle between the Israelites and the Amalekites, should be interpreted as a political document written within the framework of the royal court in Jerusalem. The purpose of the text is to define power relations among four important institutions in the government: the king, the professional military, the priests of the official cult, and the bureaucracy of the royal court. -

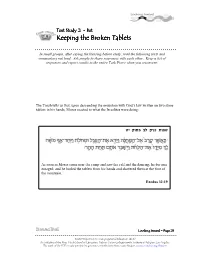

Text-Study-Keeping-The-Broken-Tablets

Text Study c --- Bet Keeping the Broken Tablets In small groups, after saying the blessing before study, read the following texts and commentary out loud. Ask people to share responses with each other. Keep a list of responses and report results to the entire Task Force when you reconvene. The Torah tells us that, upon descending the mountain with God’s law written on two stone tablets in his hands, Moses reacted to what the Israelites were doing: yh euxp ck erp ,una As soon as Moses came near the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, he became enraged; and he hurled the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain. Exodus 32:19 Looking Inward ––– Page 282828 ©2007 Experiment in Congregational Education (ECE) An Initiative of the Rhea Hirsch School of Education, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Los Angeles. The work of the ECE is made possible by generous contributions from many funders. www.eceonline.org/funders Much later, near the end of his life, Moses describes how God replaced those original tablets: v-t euxp h erp ohrcs Thereupon the Lord said to me, “Carve out two tablets of stone like the first, and come up to Me on the mountain; and make an ark of wood. I will inscribe on the tablets the commandments that were on the first tablets that you smashed, and you shall deposit them in the ark.” I made an ark of acacia wood and carved out two tablets of stone like the first; I took the two tablets with me and went up the mountain.