Shooting Sharp Images: Gear and Techniques You Need

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Tripod Head

thank you for choosing magnus. One (1) year limited warranty Congratulations on your purchase of the VPH-20 This MAGNUS product is warranted to the original purchaser Video Pan Head by Magnus. to be free from defects in materials and workmanship All Magnus Video Heads are designed to balance under normal consumer use for a period of one (1) year features professionals want with the affordability they from the original purchase date or thirty (30) days after need. They’re durable enough to provide many years replacement, whichever occurs later. The warranty provider’s of trouble-free service and enjoyment. Please carefully responsibility with respect to this limited warranty shall be read these instructions before setting up and using limited solely to repair or replacement, at the provider’s your Video Pan Head. discretion, of any product that fails during normal use of this product in its intended manner and in its intended VPH-20 Box Contents environment. Inoperability of the product or part(s) shall be determined by the warranty provider. If the product has • VPH-20 Video Pan Head Owner’s been discontinued, the warranty provider reserves the right • 3/8” and ¼”-20 reducing bushing to replace it with a model of equivalent quality and function. manual This warranty does not cover damage or defect caused by misuse, • Quick-release plate neglect, accident, alteration, abuse, improper installation or maintenance. EXCEPT AS PROVIDED HEREIN, THE WARRANTY Key Features PROVIDER MAKES NEITHER ANY EXPRESS WARRANTIES NOR ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED Tilt-Tension Adjustment Knob TO ANY IMPLIED WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY Tilt Lock OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. -

Sky-Watcher Star Adventurer Mini (SAM)

SAMStar Adventurer Mini User Guide • Astrophotography • Time-Lapse Photography • DSLR Camera Control Quite Possibly The Most Compact and Versatile Camera Tracking Platform in the Known Universe! Thank You For Purchasing This Sky-Watcher Product The Sky-Watcher Star Adventurer Mini (SAM) is a compact high-precision camera tracking platform that is ideal for long exposure astrophotography as well as time-lapse photography in daytime and nighttime settings. SAM easily fits in your backpack or camera bag, making it a convenient travel companion that can venture with you into remote locations. SAM comes with built-in WiFi and the free Star Adventurer mini Console App for Android and iOS platforms. SAM is easy to set up and easy to operate in all of its modes. The more you use it, the more you’ll love it! For your Safety To prevent damage to your Sky-Watcher product or injury to yourself or to others, all users of this product should first read the following safety precautions entirely before using this equipment. WARNING: • Do not look at the sun through the polar scope. Viewing the sun or other strong light sources through the polar scope could cause permanent visual impairment. • Do not use in the presence of flammable gas. Do not use electronic equipment in the presence of flammable gas, as this could result in explosion or fire. • Keep out of reach of children. Failure to do so could result in injury. Moreover, note that small parts constitute a choking hazard. Consult a physician immediately if a child swallows any part of this equipment. -

Pan/Tilt Head Tripod Manual #93612

PAN/TILT HEAD TRIPOD MANUAL #93612 ENGLISH INTRODUCTION Thank you for purchasing your Celestron Ultima A Pan/Tilt Head Tripod. This tripod will provide you with B C years of enjoyment and faithful service. Before using D K E your tripod for the first time, read these instructions F carefully to ensure proper use and care. G L FEATURES H M (A) Quick release plate (H) Aluminum legs (B) Quick release plate lock lever (I) Leg lock levers I (C) Bubble level (J) Rubber feet N (D) Tilt control knob (K) Pan/tilt head (E) Panning tension knob (L) Center column adjustment handle (F) Pan/tilt handle (M) Center column (G) Center column lock knob (N) Balance hook Carry case J ENGLISH I 1 USING YOUR TRIPOD The Ultima tripod will provide you with a stable platform for your spotting scope, binocular or camera in the field. With three leg sections and an adjustable center column, the tripod can be set in multiple configurations to get the exact height needed for your terrain and conditions. The Ultima is the perfect tripod for any outdoor excursion from bird watching to stargazing and everything in between. ADJUSTING THE PAN/TILT HEAD The pan/tilt head of the Ultima tripod has two control knobs. To pan with the tripod, loosen the panning tension knob until the head moves smoothly around the horizontal plane. To tilt the mounting platform, loosen the tilt control knob and adjust the mounting platform to the desired Pan/tilt handle position. Once the tripod is in position, tighten Tilt control the tension knobs to secure. -

Camera Support Equipment

CAMERA SUPPORT EQUIPMENT www.libec-global.com Heads, Tripod Systems & Monopod Pedestal Systems Jib, Remote Head & Tracking Rails Remote Controls Tripods & Cases Accessories Specifications are subject to change without notice. The colors in this brochure may differ from actual products because of the printing color inks or photographic conditions. 17/03 2017/18 CONTENTS 3 Heads,Tripod Systems & Monopod 49 Tracking Rails 4 Counterbalance 50 Remote Controls, Tripods & Accessories 6 RSPLUS 51 Remote Controls 13 RS 54 Tripods 19 LX 57 Tripod Cases 23 LIBEC ALLEX 59 Accessories 29 TH-X 61 Specications Beyond Quality Support 32 HFMP 37 Pedestal Systems 41 Jib, Remote Head & Tracking Rails 42 SWIFT JIB 45 REMOTE HEAD 2014 tv asahi/TOEI AG/TOEI 1 2 Heads, Tripod Systems & Monopod Counterbalance Importance of Counterbalance When looking for a suitable tripod head for your camera, one of the most important aspects to consider is counterbalancing capability. The counterbalancing function provides a counterforce to keep the balance between the & Monopod Systems Tripod Heads, tripod head and the camera that is mounted on it. If the right counterbalance is maintained, the camera remains stationary at any angle of tilt. You do not need to worry about holding the camera by hand and yet are able to maintain precise control of the camera. RS/RSPLUS Counterbalancing Capability The RS/RSPLUS is equipped with an excellent counterbalancing system that provides a perfect counterforce that corresponds to the weight and angle of the camera. A special innerspring mechanism is used for this Fine-tunable counterbalance knob system. When the strength of a spring is insufficient, the head cannot bear the weight of the camera. -

Ricoh Theta S in Astronomy Erwin Matys, Karoline Mrazek

Ricoh Theta S in Astronomy Erwin Matys, Karoline Mrazek The Theta S camera is a valuable tool for a multitude of applications in astronomy and astrophotography. The Ricoh Theta S is a completely new type of camera. With two fisheye lenses it records a 360° full-sphere panorama in only one single shot. The recorded images can be further processed and viewed either with the player provided by the manufacturer or with any third-party panorama viewer or web service that supports full-sphere panoramas. When used stand-alone, the camera works only in automatic mode. Controlling the camera with the provided app on a mobile device gives the user much more options: Long exposures, timed exposure series, HDR shooting, image download, immediate viewing as a sphere on the mobile device, etc. For a more thorough introduction to the camera system and to view some terrestrial sample shots, visit the manufacturer's Theta S website theta360.com. Night Sky Suitability of the Theta S Image: Ricoh press release Before we discuss some astronomical applications in more detail, here are the basic facts about the camera's suitability for night sky photography: First of all, to use the manual mode and to set exposure time, ISO and white balance individually (as it is required for night sky photography) the camera must be controlled by the provided app running on a smartphone or tablet. This procedure is straightforward, the camera connects with the mobile device via Wi-Fi and the app is easy to understand and simple to use. For night sky photography the camera must be mounted on a tripod - for this, the camera provides a standard 1/4" thread in the base. -

Using a Tripod

Using a Tripod PUBLISHED - 28 APR 2016 Tripods were absolutely essential in the early days of photography, when exposures were made on glass plates with sensitivity as low as just ISO 1-3. These days, with many Nikon cameras able to capture a black cat in a coal cellar hand-held, thanks to the incredible leaps ISO capability has made, you might be thinking, do I really need a tripod? But the answer is still 'yes' for many types of images and situations – find out why in our comprehensive guide… So why use a tripod? Tripods come in handy for many different reasons - read on to find out when you might need one.... Sharper images The more pixels your camera's sensor packs, the more likely it is that tiny movements will be recorded as blur in your shots, so with a high-megapixel DSLR such as the D810, it's definitely worth using it tripod-mounted at anything under 1/125sec. Even at fast shutter speeds, blur is less likely with the camera rock-steady on a tripod (always using a cable release to fire the shutter) – and the larger you're intending to display your image, the more important this becomes. 1 of 5 Spot-on composition Using a tripod slows you down a bit, giving you the time and space to perfect your composition, getting everything level and double-checking the exposure, the depth of field, and what's in and out of frame. If you want to shoot multiple frames at different exposure settings, such as for high-dynamic range (HDR) images, using a tripod is the best way to ensure you keep the composition perfectly the same between frames; it also enables you to shoot panoramas with each component shot on the same plane. -

L E N S E S & a C C E S S O R I

P. 4 P. 5 P. 6 P. 7 Scott Grant / Hai Tre / Jeff Carter / Gathot Subroto / Canada Vietnam UK Indonesia P. 8 P. 9 P.10 Matt Hart / Bert Stephani / Max De Martino / UK Belgium Italy P.11 P.12 P.13 P.14 Omar Z Robles / Simone Sbarglia / Pål Laukli / LS Trung / U.S.A. Italy Norway Vietnam P.15 P.16 P.17 Yonghui Wang / Supalerk Fabian De Backer / China Narubetkrausee / Belgium Thailand P.18 P.19 P.20 Taeyoung An / Joe Ng / Chalit Padoongcheep / Korea Canada Thailand P.21 P.21 Torwong Salwala / Giulia Torra / Thailand Italy Cover_P.2-3 Jonas Dyhr Rask / Denmark Specifications are subject to change without notice. LENSES & ACCESSORIES For more information, please visit our website: http://www.http://fujifilm-x.com/en/accessories/ c 2016 FUJIFILM Corporation P2-3/P36 The vision of the X Series, the choice for X Series owners A collection of creativity-oriented lenses, which complement the X-Trans CMOS sensor perfectly and eliminate the low-pass filter for ultimate sharpness. X Mount Lenses _ P.4-21 Accessories _ P.23-29 Technology _ P.30-33 Specifications _ P.34-35 2 3 P4-5/P36 XF14mmF2.8 R XF16mmF1.4 R WR X-T2 : F11 1/4 sec. ISO200 Scott Grant / Canada High resolving power across the frame from the centre to the edges. This ultra-wide-angle lens, which has a diagonal angle of view greater than 90°, produces extraordinary images. Distortion has been kept to a measured value of zero, with sharpness right across the frame, even when the subject is near the edges. -

Panoramas Made Simple How to Create Beautiful Panoramas with the Equipment You Have—Even Your Phone Hudson Henry

PANORAMAS MADE SIMPLE HOW TO CREATE BEAUTIFUL PANORAMAS WITH THE EQUIPMENT YOU HAVE—EVEN YOUR PHONE HUDSON HENRY PANORAMAS MADE SIMPLE How to create beautiful panoramas with the equipment you have—even your phone By Hudson Henry Complete Digital Photography Press Portland, Oregon Copyright ©2017 Hudson Henry All rights reserved. First edition, November 2017 Publisher: Rick LePage Design: Farnsworth Design Published by Complete Digital Photography Press Portland, Oregon completedigitalphotography.com All photography ©Hudson Henry Photography, unless otherwise noted. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE MY PASSION FOR PANORAMAS 1 3 CAPTURING THE FRAMES 26 How is this book organized? Lens selection Exposure metering AN INTRODUCTION TO PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY 1 5 Use a tripod Go wide and with more detail The importance of being level Simple panoramas defined Orient your camera Not all panoramas are narrow slices Focus using live view Equipment for simple panoramas Beware of polarizers or graduated filters Advanced panoramas Marking your panoramas Compose wide and use lots of overlap 2 THINKING ABOUT LIGHT, FOCUS AND SETUP 12 Move quickly and carefully Light and composition: the rules still apply Watch out for parallax 4 ASSEMBLING YOUR PANORAMA 35 Finding the infinity distance My workflow at a glance Learning how to lock your camera settings Building panoramas with Lightroom Classic CC Why shouldn’t I use my phone’s automatic panorama mode? Working with Photoshop CC to create panoramas Why is manual exposure so important? Building panoramas in ON1 Photo RAW 2018 5 RESOURCES 52 Links PREFACE MY PASSION FOR PANORAMAS My first panorama, I GREW UP WITH ADVENTURESOME EXTENDED FAM- with image quality. -

E-Image Tripod User Manual

User s Manual PREFACE FLUID HEAD Thank you for purchasing E-IMAGE professional heads and The E-IMAGE GENTING Series is an upgraded generation tripods. This manual is an important tool for personnel who of E-Image fluid heads with international operate and maintain this equipment. Inside, you will influences, innovative designs, and more advanced find detailed information about E-IMAGE tripods and functions. We refined the counterbalance and drag heads, and their proper use. We highly recommend you read systems, making balancing faster and simpler. This new the manual carefully and familiarize yourself with each series can handle a wider payload range, from 8.8 to 55 section. There is also a section about safety and pounds, and works with many different styles of camera. Pan maintenance to help you keep your equipment in perfect handles with rubber grips are included for precise camera condition and extend its life. movements and are extendable in some models. Each head also has an installed bubble level, and advanced Please keep this manual for reference while operating and heads have an LED light installed for making maintaining your equipment. adjustments in the dark. CONTENTS CONTENTS Fluid Head Specifications.………………….......... 1 Tripod Specifications…………………………………………..15-16 Parts(GH03)……………………………….................. 2 Parts(AT7402A) ……………………………………………...........17 Set up & Use..............……………………….......... 3-5 Use AT7402A ……………………………………………...........18-19 1. Installing the Pan Handle.……………...................... 3 1. Releasing and Locking the Legs.....……………….......................18 2. Remov …....................... 3 ing the Quick Release Plate 2. Adjusting Tripod Height…………..………………..........................18 3. Adjusting Tilt Position……………….......................... 4 3. Anti-Slip Rubber Feet……………………………............................18 4. Adjusting Pan Position………………......................... 4 4. Folding the Tripod for Storage...………………........................... -

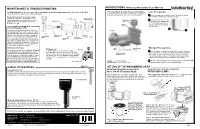

MH-100) MAINTENANCE & TROUBLESHOOTING: the Monogimbal Has Been Designed and Constructed to Handle Many Maintenance Free Years in the Field

INSTRUCTIONS: Wimberley MonoGimbal Head (MH-100) MAINTENANCE & TROUBLESHOOTING: The MonoGimbal has been designed and constructed to handle many maintenance free years in the field. It is important to read these instructions. Lens Prerequisites There should be no need for any routine maintenance. Setting up the MonoGimbal Head is not difficult, but reading these instructions will allow you to get the most out of the product. 1 Your lens must have a rotation collar if you wish to quickly If your head has been exposed to a large switch between landscape and portrait modes Stainless Steel amount of salt water, sand or grit it can be Thrust Washer easily disassembled and rinsed. If you need to Captivating Screw Quick-Release 2 Your lens must have an Arca- Nylon Washer Knob disassemble the tilt mechanism refer to the Knob Swiss style quick-release plate drawing to the right or a Lens Replacement Foot Moving with an integrated Arca-Swiss Jaw IF YOU HAVE A PROBLEM WITH style dovetail. YOUR MONOGIMBAL HEAD: 1 Few things are likely to go wrong with the Wimberley Tilt Knob 2 MonoGimbal Head However, if the head is in need of repair, we ask that you return the head to us for inspec- tion and service. (International customers should con- Stainless Steel Cover for tact the dealer who sold you the MonoGimbal Head). Quick-Release Tilt Shaft Clamp Radial Roller Bearing Assembly Safety Stop Thrust Bearing If you need a head for a trip or shoot while yours is be- Screw ing repaired, let us know and we can send you one on loan. -

Nikon's D800 Technical Guide

Technical GuideTechnical Guide Introduction Table of Contents This “Technical Guide” details the principal techniques used IIntroductionntroduction ii to create two of the more technically advanced photographs in the D800/D800E catalog. Enjoy this opportunity to admire SShootinghooting TTechniquesechniques 1 the skills of professional photographers who have mastered the D800/D800E. Static Subjects ...........................................................................1 • Lesson 1: Use a Tripod ..................................................................2 While its high pixel count of 36 megapixels gives the D800/ D800E resolution unrivalled by previous digital SLR cameras, • Lesson 2: Use Live View ............................................................... 3 a side eff ect is that bokeh and blur are made that much more • Lesson 3: Don’t Stop Aperture Down Too Far ......................5 obvious. Realizing the full potential of a camera with over • Same Shot, No Live View .............................................................6 30 million pixels involves a thorough appreciation of bokeh Portrait Subjects........................................................................7 and blur, careful selection of settings and of tools (such as • Lesson 1: Choose the Right Focus Settings ..........................8 lenses and tripods), and working with the best possible sub- • Lesson 2: Choose the Right Exposure Settings ...................9 jects. • Learning from Failure: Same Shot, Diff erent Focus .........10 QQuickuick -

Appendix a Planning an Astrophotography Imaging Session

Appendix A Planning an Astrophotography Imaging Session One way to obtain a high percentage of successful photographs is to look at imaging a deep space object as a project. The first step of any project is to define the project’s goals and objectives followed by detailed planning and then executing the plan. Perhaps the best way to explain an astrophotography project is by an example. For our example, let’s assume a location at 38° north latitude in a suburban area with moderate levels of light pollution with a skyglow of magnitude 19 per arcsec- ond squared. The imaging kit is an Orion ST-80A 80 mm f/5 refractor, a Canon EOS T3/1100D camera with an interval timer and a Celestron 4 SE mount on a wedge. The current time of the year is early summer and we see an image of the galaxy NGC 2403 posted by someone on an internet forum, in an astronomy maga- zine, etc. The galaxy looks interesting and we decide that we would like to make our own image of it. Before getting heavily involved in planning we need answers to the following questions: • Is the galaxy visible at our viewing location? • When is the optimum time to photograph the galaxy? • Is our equipment capable of capturing a decent image of NGC 2403? The literature tells us that NGC 2403 has an apparent magnitude 8.4, an apparent size of 21.4 × 10.7 arcminutes, and is located in the Constellation Camelopardalis. It is object number 7 in the Caldwell list for small telescopes and is often observed with a pair of binoculars.