Milton Friedman on Freedom and the Negative Income Tax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rent-Seeking Contests with Incomplete Information

Rent-Seeking Contests with Incomplete Information Mark Fey∗ Department of Political Science University of Rochester September, 2007 Abstract We consider rent-seeking contests with two players that each have private information about their own cost of effort. We consider both discrete and continuous distributions of costs and give results for each case, focusing on existence of equilibria. JEL Classification: D72; C72 Keywords: rent-seeking, contests, conflict, private information, equi- librium existence ∗Harkness Hall, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, 14618. Office: 585-275-5810. Fax: 585-271-1616. Email: [email protected]. 1 Introduction A rent-seeking contest is a situation in which players expend costly effort to gain a reward. Many conflict situations can be described by rent-seeking contests, including political campaigns, patent races, war fighting, lobbying efforts, labor market competition, legal battles, and professional sports. The reward in a rent-seeking contest may be indivisible, such as electoral office or a patent right, or it may be divisible, such as market share or vote share. In the former case, expending more effort increases the probability that a player will win the prize. In the latter case, expending more effort increases the share of the prize. An important vehicle for investigating the logic of rent-seeking contests is the model of Tullock (1980). This work has spawned a large literature, some of which is surveyed in Lockard and Tullock (2001) and Corch´on (2007). In this paper, we contribute to this literature by developing a model of rent- seeking contests in which players have incomplete information about the cost of effort to other players. -

Buchanan, James and Tullock, Gordon. the Calculus of Consent

BOOKS AUTHORED AND CO-AUTHORED Tullock, Gordon. The Logic of the Law (New York: Basic (page 1: 1965-1980) Books Inc., 1971). University Press of America, 1988. Buchanan, James and Tullock, Gordon. The Calculus of Tullock, Gordon. The Social Dilemma: The Economics of Consent: Logical Foundations of a Constitutional War and Revolution (Blacksburg, VA: Center for Study Democracy (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, of Public Choice, 1974). 1962). Paperback, 1965. Japanese Translation, 1979. Spanish Translation, 1980. Slovenian Translation, March 1997. Japanese Translation, 1980. Russian Translation, 2001 McKenzie, Richard B. and Tullock, Gordon. The New World Chinese Translation (by Yi Xianrong), forthcoming of Economics: Explorations into the Human Korean Translation (by Sooyoun Hwang), Forward Experience (Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, Inc., French Translation, forthcoming 1975). 2nd Edition, 1978. 3rd Edition, 1980. 4th Edition, 1984. Chapter 4, “Competing monies,” (Irwin, 1984, Tullock, Gordon. The Politics of Bureaucracy (Washington 4th ed. Pp. 52-65). 5th Edition, 1989. Revised Aug. D.C.: Public Affairs Press, 1965). Paperback, 1975. 1994 and retitled: The Best of the New World of University Press of America, 1987. Economics… and Then Some. 5th Edition reissued, 1994, The New World of Economics. McGraw-Hill). Tullock, Gordon. The Organization of Inquiry (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1966). University Press of Spanish Translation, 1980. America, 1987. Japanese Translation, 1981. German Translation, 1984. Tullock, Gordon. Toward a Mathematics of Politics (Ann Chinese Translation, 1992. Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1967). Paperback, 1972. [Reviewed by Kenneth J. Arrow. McKenzie, Richard B. and Tullock, Gordon. Modern Political “Tullock and an Existence Theorem,” Public Choice, Economy: An Introduction to Economics (New York: VI: 105-11.] McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1978). -

Taxation Paradigms: JOHN WEBB SUBMISSION APRIL 2009

Taxation Paradigms: What is the East Anglian Perception? JOHN WEBB A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SUBMISSION APRIL 2009 BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY What we calf t[ie beginningis oftenthe end And to makean endis to makea beginning ?fie endis wherewe start ++++++++++++++++++ Weshall not ceasefrom exploration And the of exploring end .. Wilt to arrivewhere we started +++++++++++++++++ 7.S f: Cwt(1974,208: 209) ? fie Four Quartets,Coffected Poems, 1909-1962 London: Faderand Fader 2 Acknowledgements The path of a part time PhD is long and at times painful and is only achievablewith the continued support of family, friends and colleagues. There is only one place to start and that is my immediate family; my wife, Libby, and daughter Amy, have shown incredible patienceover the last few years and deserve my earnest thanks and admiration for their fantastic support. It is far too easy to defer researchwhilst there is pressingand important targets to be met at work. My Dean of Faculty and Head of Department have shown consistent support and, in particular over the last year my workload has been managedto allow completion. Particularthanks are reservedfor the most patientand supportiveperson - my supervisor ProfessorPhilip Hardwick.I am sure I am one of many researcherswho would not have completed without Philip - thank you. ABSTRACT Ever since the Peasant'sRevolt in 1379, collection of our taxes has been unpopular. In particular when the taxes are viewed as unfair the population have reacted in significant and even violent ways. For example the Hearth Tax of 1662, Window Tax of 1747 and the Poll tax of the 1990's have experiencedpublic rejection of these levies. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

The Macroeconomics Effects of a Negative Income

The Macroeconomics e¤ects of a Negative Income Tax Martin Lopez-Daneri Department of Economics The University of Iowa February 17, 2010 Abstract I study a revenue neutral tax reform from the actual US Income Tax to a Negative Income Tax (N.I.T.) in a life-cycle economy with individual heterogeneity. I compare di¤erent transfers in a stationary equilibrium. I …nd that the optimal tax rate is 19.51% with a transfer of 11% of GDP per capita, roughly $5,172.79. The average welfare gain amounts to a 1.7% annual increase of individual consumption. All agents bene…t from the reform. There is a 17.52% increase in GDP per capita and a decrease of 13% in Capital per labor. Capital per Output declines 10.22%. 1 Introduction The actual US Income Tax has managed to become increasingly complex, because of its numerous tax credits, deductions, overlapping provisions and increasing marginal rates. The Income Tax introduces a considerable number of distortions in the economy. There have been several proposals to simplify it. However, this paper focuses on one of them: a Negative Income Tax (NIT). In this paper, I ask the following questions: What are the macroeconomic e¤ects of replacing the Income Tax with a Negative Income Tax? Speci…cally, is there any welfare gain from this Revenue-Neutral Reform? Particularly, I am considering a NIT that taxes all income at the same marginal rate and 1 makes a lump-sum transfer to all households. Not only does the tax proposed is simple but also all households have a minimum income assured. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Forms of Government

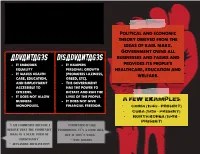

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

![The Selected Works of Gordon Tullock, Vol. 3 the Organization of Inquiry [1966]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4622/the-selected-works-of-gordon-tullock-vol-3-the-organization-of-inquiry-1966-444622.webp)

The Selected Works of Gordon Tullock, Vol. 3 the Organization of Inquiry [1966]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Gordon Tullock, The Selected Works of Gordon Tullock, vol. 3 The Organization of Inquiry [1966] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Volume 3: Value-Added

re Volume 3 Value-Added Tax Office of- the Secretary Department of the Treasury November '1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume Three Page Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter 2: THE NATURE OF THE VALUE-ADDED TAX I. Introduction TI. Alternative Forms of Tax A. Gross Product Type B. Income Type C. Consumption Type 111. Alternative Methods of Calculation: Subtraction, Credit, Addition 7 A. Subtraction Method 7 8. Credit Method 8 C. Addition Method 8 D. Analysis and Summary 10 IV. Border Tax Adjustments 11 V. Value-Added Tax versus Retail Sales Tax 13 VI. Summary 16 Chapter -3: EVALUATION OF A VALUE-ADDED TAX 17 I. Introduction 17 11. Economic Effects 17 A. Neutrality 17 B. saving 19 C. Equity 19 D. Prices 20 E. Balance of Trade 21 III. Political Concerns 23 A. Growth of Government 23 B. Impact on Income Tax 26 C. State-Local Tax Base 26 Iv. European Adoption and Experience 27 Chapter 4: ALTERNATIVE TYPES OF SALES TAXATION 29 I. Introduction 29 11. Analytic Framework 29 A. Consumption Neutrality 29 E. Production and Distribution Neutrality 30 111. Value-Added Tax 31 IV. Retail Sales Tax 31 V. Manufacturers and Other Pre-retail Taxes 33 VI. Personal Exemption Value-Added Tax 35 VII. Summary 38 iii Page Chapter 5: MAJOR DESIGN ISSUES 39 I. Introduction 39 11. Zero Rating versus Exemption 39 A. Commodities 39 B. Transactions 40 C. Firms 40 D. Consequences of zero Rating or Exemption 41 E. Tax Credit versus Subtraction Method 42 111. The Issue of Regressivity 43 A. Adjustment of Government Transfer Payments 43 B. -

GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58Th Street, Chicago, Ill

THE PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF ECONOMICS Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December, 1982 by GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58th Street, Chicago, Ill. 60637, USA In the work on the economics of information which I began twenty some years ago, I started with an example: how does one find the seller of automobiles who is offering a given model at the lowest price? Does it pay to search more, the more frequently one purchases an automobile, and does it ever pay to search out a large number of potential sellers? The study of the search for trading partners and prices and qualities has now been deepened and widened by the work of scores of skilled economic theorists. I propose on this occasion to address the same kinds of questions to an entirely different market: the market for new ideas in economic science. Most economists enter this market in new ideas, let me emphasize, in order to obtain ideas and methods for the applications they are making of economics to the thousand problems with which they are occupied: these economists are not the suppliers of new ideas but only demanders. Their problem is comparable to that of the automobile buyer: to find a reliable vehicle. Indeed, they usually end up by buying a used, and therefore tested, idea. Those economists who seek to engage in research on the new ideas of the science - to refute or confirm or develop or displace them - are in a sense both buyers and sellers of new ideas. They seek to develop new ideas and persuade the science to accept them, but they also are following clues and promises and explorations in the current or preceding ideas of the science. -

Liberty, Property and Rationality

Liberty, Property and Rationality Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Master’s Thesis Hannu Hästbacka 13.11.2018 University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts General History Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Hannu Hästbacka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Liberty, Property and Rationality. Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Yleinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma year 100 13.11.2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) on yksi keskeisimmistä modernin libertarismin taustalla olevista ajattelijoista. Rothbard pitää yksilöllistä vapautta keskeisimpänä periaatteenaan, ja yhdistää filosofiassaan klassisen liberalismin perinnettä itävaltalaiseen taloustieteeseen, teleologiseen luonnonoikeusajatteluun sekä individualistiseen anarkismiin. Hänen tavoitteenaan on kehittää puhtaaseen järkeen pohjautuva oikeusoppi, jonka pohjalta voidaan perustaa vapaiden markkinoiden ihanneyhteiskunta. Valtiota ei täten Rothbardin ihanneyhteiskunnassa ole, vaan vastuu yksilöllisten luonnonoikeuksien toteutumisesta on kokonaan yksilöllä itsellään. Tutkin työssäni vapauden käsitettä Rothbardin anarko-kapitalistisessa filosofiassa. Selvitän ja analysoin Rothbardin ajattelun keskeisimpiä elementtejä niiden filosofisissa, -

Hayek's Relevance: a Comment on Richard A. Posner's

HAYEK’S RELEVANCE: A COMMENT ON RICHARD A. POSNER’S, HAYEK, LAW, AND COGNITION Donald J. Boudreaux* Frankness demands that I open my comment on Richard Posner’s essay1 on F.A. Hayek by revealing that I blog at Café Hayek2 and that the wall-hanging displayed most prominently in my office is a photograph of Hayek. I have long considered myself to be not an Austrian economist, not a Chicagoan, not a Public Choicer, not an anything—except a Hayekian. So much of my vi- sion of reality, of economics, and of law is influenced by Hayek’s works that I cannot imagine how I would see the world had I not encountered Hayek as an undergraduate economics student. I do not always agree with Hayek. I don’t share, for exam- ple, his skepticism of flexible exchange rates. But my world view— my weltanschauung—is solidly Hayekian. * Chairman and Professor, Department of Economics, George Mason University. B.A. Nicholls State University, Ph.D. Auburn University, J.D. University of Virginia. I thank Karol Boudreaux for very useful comments on an earlier draft. 1 Richard A. Posner, Hayek, Law, and Cognition, 1 NYU J. L. & LIBERTY 147 (2005). 2 http://www.cafehayek.com (last visited July 26, 2006). 157 158 NYU Journal of Law & Liberty [Vol. 2:157 I have also long admired Judge Posner’s work. (Indeed, I regard Posner’s Economic Analysis of Law3 as an indispensable resource.) Like so many other people, I can only admire—usually with my jaw to the ground—Posner’s vast range of knowledge, his genius, and his ability to spit out fascinating insights much like I imagine Vesuvius spitting out lava.