Reading from Experience: Toward an Ethnography of Reading at Tulalip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory

Where the Water Meets the Land: Between Culture and History in Upper Skagit Aboriginal Territory by Molly Sue Malone B.A., Dartmouth College, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Molly Sue Malone, 2013 Abstract Upper Skagit Indian Tribe are a Coast Salish fishing community in western Washington, USA, who face the challenge of remaining culturally distinct while fitting into the socioeconomic expectations of American society, all while asserting their rights to access their aboriginal territory. This dissertation asks a twofold research question: How do Upper Skagit people interact with and experience the aquatic environment of their aboriginal territory, and how do their experiences with colonization and their cultural practices weave together to form a historical consciousness that orients them to their lands and waters and the wider world? Based on data from three methods of inquiry—interviews, participant observation, and archival research—collected over sixteen months of fieldwork on the Upper Skagit reservation in Sedro-Woolley, WA, I answer this question with an ethnography of the interplay between culture, history, and the land and waterscape that comprise Upper Skagit aboriginal territory. This interplay is the process of historical consciousness, which is neither singular nor sedentary, but rather an understanding of a world in flux made up of both conscious and unconscious thoughts that shape behavior. I conclude that the ways in which Upper Skagit people interact with what I call the waterscape of their aboriginal territory is one of their major distinctive features as a group. -

SKAGIT COOPERATIVE WEED MANAGEMENT AREA Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Program 2013 Season Ending Report

SKAGIT COOPERATIVE WEED MANAGEMENT AREA Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Program 2013 Season Ending Report Sauk River during 2013 knotweed surveys. Prepared by: Michelle Murphy Stewardship Manager Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group PO Box 2497 Mount Vernon, WA 98273 Introduction In the 2013 season, the Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group (SFEG) and our partners with the Skagit Cooperative Weed Management Area (CWMA) or Skagit Knotweed Working Group, completed extensive surveys of rivers and streams in the Upper Skagit watershed, treating knotweed in a top-down, prioritized approach along these waterways, and monitoring a large percentage of previously recorded knotweed patches in the Upper Skagit watershed. We continued using the prioritization strategy developed in 2009 to guide where work is completed. SFEG contracted with the Washington Conservation Corps (WCC) crew and rafting companies to survey, monitor and treat knotweed patches. In addition SFEG was assisted by the DNR Aquatics Puget Sound Corps Crew (PSCC) in knotweed survey and treatment. SFEG and WCC also received on-the-ground assistance in our efforts from several Skagit CWMA partners including: U.S. Forest Service, Seattle City Light and the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe. The Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe received a grant from the EPA in 2011 to do survey and treatment work on the Lower Sauk River and in the town of Darrington through 2013. This work was done in coordination with SFEG’s Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Project. The knotweed program met its goal of surveying and treating both the upper mainstem floodplains of the Sauk and Skagit Rivers. SFEG and WCC surveyed for knotweed from May through June and then implemented treatment from July until the first week of September. -

B.18: Skagit County Public Utilities District (PUD)

B.18: Skagit County Public Utilities District (PUD) www.skagitpud.org Skagit Public Utility District Number 1 (Skagit PUD) Resource conservation and stewardship are increasing concerns of the operates the largest water system in the county, PUD. Recognizing the value of water resources in Skagit County, the providing 9,000,000 gallons of piped water to PUD is a member of the Skagit Watershed Council and is actively approximately 70,000 people every day. The PUD participating in efforts to protect ins-stream flows. maintains nearly 600 miles of pipelines and has over 31,000,000 gallons of storage volume. The vision of the PUD - is to be recognized as an outstanding regional leader and innovative utility provider that embodies environmental Mount Vernon, Burlington, and Sedro-Woolley receive the majority of stewardship and sound economic practices. the PUD’s water. Due to public demand for quality water, the PUD also provides service to unincorporated and remote areas of the county. The mission of the PUD - is to provide quality, safe, reliable, and The District’s service area includes part of Fidalgo Island at the west affordable utility services to its customers in an environmentally- end of the county and extends as far east as Marblemount. From north responsible, collaborative manner. to south, the District’s service area starts in Conway and extends north to Alger/Lake Samish. The values of the PUD are: PUD water originates in the protected Cultus Mountain watershed area Quality east of Clear Lake from 4 streams. Melting snow and season rainfall Reliability are diverted from an uninhabited, 9 square mile, forested area, located Environmental responsibility high about the mountains. -

Monte Cristo Road Map MONTE CRISTO PRESERVATION ASSOCIATION (4 Miles Not to Scale) in the 1890S Monte Cristo Lay Far from Any Road Or Navigable River

WWW.MCPA.US photographs, and ruins. and photographs, Visit our website at: website our Visit keep this guide handy to help identify the signs, signs, the identify help to handy guide this keep Everett, WA. 98206 WA. Everett, yards. As you walk the once-bustling streets and trails, trails, and streets once-bustling the walk you As yards. P.O. Box 471 Box P.O. along Dumas Street or the lower area below the railway railway the below area lower the or Street Dumas along Monte Cristo Preservation Association Preservation Cristo Monte a school, a newspaper, and residences, mostly situated situated mostly residences, and newspaper, a school, a Provided by the the by Provided required by an isolated industrial town: stores, five hotels, five stores, town: industrial isolated an by required the railway. At the townsite were all the support services services support the all were townsite the At railway. the concentrator (pictured right) for processing and then to then and processing for right) (pictured concentrator carried the minerals down the steep mountainsides to the the to mountainsides steep the down minerals the carried Wilmans and Foggy peaks, from which aerial tramways tramways aerial which from peaks, Foggy and Wilmans Most of the miners lived high above the town on on town the above high lived miners the of Most built to connect the mines with their smelter at Everett. at smelter their with mines the connect to built South Fork Sauk River, and a standard guage railway was railway guage standard a and River, Sauk Fork South peninsula between Glacier and 76 creeks at the head of the of head the at creeks 76 and Glacier between peninsula millions of dollars in ore, a town sprang up on the on up sprang town a ore, in dollars of millions A Gold Mining Town of the 1890s the of Town Mining Gold A then and 1907 the mines above the town produced produced town the above mines the 1907 and then bearing ore at a site soon named Monte Cristo. -

Geologic Map of Washington - Northwest Quadrant

GEOLOGIC MAP OF WASHINGTON - NORTHWEST QUADRANT by JOE D. DRAGOVICH, ROBERT L. LOGAN, HENRY W. SCHASSE, TIMOTHY J. WALSH, WILLIAM S. LINGLEY, JR., DAVID K . NORMAN, WENDY J. GERSTEL, THOMAS J. LAPEN, J. ERIC SCHUSTER, AND KAREN D. MEYERS WASHINGTON DIVISION Of GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-50 2002 •• WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF 4 r Natural Resources Doug Sutherland· Commissioner of Pubhc Lands Division ol Geology and Earth Resources Ron Telssera, Slate Geologist WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Ron Teissere, State Geologist David K. Norman, Assistant State Geologist GEOLOGIC MAP OF WASHINGTON NORTHWEST QUADRANT by Joe D. Dragovich, Robert L. Logan, Henry W. Schasse, Timothy J. Walsh, William S. Lingley, Jr., David K. Norman, Wendy J. Gerstel, Thomas J. Lapen, J. Eric Schuster, and Karen D. Meyers This publication is dedicated to Rowland W. Tabor, U.S. Geological Survey, retired, in recognition and appreciation of his fundamental contributions to geologic mapping and geologic understanding in the Cascade Range and Olympic Mountains. WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-50 2002 Envelope photo: View to the northeast from Hurricane Ridge in the Olympic Mountains across the eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca to the northern Cascade Range. The Dungeness River lowland, capped by late Pleistocene glacial sedi ments, is in the center foreground. Holocene Dungeness Spit is in the lower left foreground. Fidalgo Island and Mount Erie, composed of Jurassic intrusive and Jurassic to Cretaceous sedimentary rocks of the Fidalgo Complex, are visible as the first high point of land directly across the strait from Dungeness Spit. -

Mapping of Major Latest Pleistocene to Holocene Eruptive Episodes from the Glacier Peak Volcano, Washington—A Record of Lahar

MAPPING OF MAJOR LATEST PLEISTOCENE TO HOLOCENE ERUPTIVE EPISODES FROM THE GLACIER PEAK VOLCANO, WASHINGTON—A RECORD OF LAHARIC INUNDATION OF THE PUGET LOWLANDS FROM DARRINGTON TO THE PUGET SOUND 123° 122° 121° 49° Benjamin W. Stanton and Joe D. Dragovich, Washington Department of Natural Resouces, Division of Geology and Earth Resources, 1111 Washington St SE, Olympia, WA 98504-7007, [email protected] and [email protected] map area Bellingham SAN WHA TCOM 20 JUAN Volcanic hazards in the Pacific Northwest are typically associated with more visible stratovolcanoes, such as Mount Rainier. Glacier Peak, a North Cascade dacitic stratovolcano near Darrington, Washington, has produced at least three large eruptive episodes See Figure 2 14 path of lahars since the culmination of the last continental glaciation with each episode likely lasting a few hundred years. Data from recent detailed geologic mapping, new C ages, stratigraphic relations, clast petrographic analyses, geochemical analyses, and laharic SKAGIT to lower Skagit Valley ISLAND sand composition indicate that three large eruptive episodes occurred in the latest Pleistocene and Holocene—the information refines and expands on the pioneering work of Beget (1981). These voluminous events traveled up to 135 km downvalley of the path of lahars to lower Stillaguamish Valley Glacier Peak edifice and reached the Puget Sound via the ancient Skagit and Stillaguamish deltas. Glacier Peak has erupted dacite of similar composition throughout its history. Hypersthene-hornblende-(augite)-phyric vesicular lahar clasts found from Glacier Peak to La volcano 48° SNOHMISH Conner, Washington have similar geochemistry to dacite flows sampled on the volcano. Radiocarbon dating of the White Chuck assemblage shows an eruptive episode of ~11,900 yrs B.P. -

1. Skagit Basin Overview

1. Skagit Basin Overview Abstract Since the 1850s, the Skagit River basin has been altered by human activities such as logging, diking, and the construction of dams, roads, levees, and tide gates. Logging and construction of levees and dikes converted coniferous forest and wetlands to farmland, industrial, and urban/suburban residential development. Dams constructed in the Skagit River not only generate hydropower but also provide flood control, recreation opportunities, and diverse ecosystem services. Major highways constructed through Skagit County promoted both economic and population growth in Skagit County. These human developments have dramatically impacted the hydrology and geomorphology of the basin and have impacted or reduced habitat for a wide range of species, including multiple species of native anadromous fish historically reliant on Skagit River Basin tributaries. Low-lying farms, urban development, and other lands in the floodplain are currently vulnerable to river flooding and sea level rise. The economy of the Skagit River basin in the 19th and early 20th centuries was focused primarily on logging, mining, and agriculture, but has diversified through the second half of the 20th century. Rapid increases in population in the 21st century are projected for Skagit Co., which, under the Growth Management Act and the Skagit County Comprehensive Plan, will direct future growth primarily in urban areas. 1.1 Overview of the Skagit River Basin The Skagit River basin is located in southwestern British Columbia in Canada and northwestern Washington in the United States (Figure 1.1) and drains an area of 3,115 square miles (Pacific International Engineering, 2008). Major tributaries in the basin are the Baker River, Cascade River, and Sauk River. -

Each Grantee for 04 Must Submit A

SKAGIT COOPERATIVE WEED MANAGEMENT AREA Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Program 2015 Season Ending Report 10/06/2015 Sauk River during 2015 knotweed surveys. Prepared by: Michelle Murphy Stewardship Manager Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group PO Box 2497 Mount Vernon, WA 98273 Introduction In the 2015 season, the Skagit Fisheries Enhancement Group (SFEG) and our partners with the Skagit Cooperative Weed Management Area (CWMA) or Skagit Knotweed Working Group, completed extensive surveys of rivers and streams in the Upper Skagit watershed, treating knotweed in a top-down, prioritized approach along these waterways, and monitoring a large percentage of previously recorded knotweed patches in the Upper Skagit watershed. We continued using the prioritization strategy developed in 2009 to guide where work is completed. SFEG contracted with the Washington Conservation Corps (WCC) crew and rafting companies to survey, monitor and treat knotweed patches. In addition SFEG also received on-the-ground assistance in our efforts from several Skagit CWMA partners including: U.S. Forest Service, Seattle City Light, National Park Service and the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe. The Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe received a grant from the EPA in 2011 to perform survey and treatment work on the Lower Sauk River and in the town of Darrington through 2015. This work was done in coordination with SFEG’s Upper Skagit Knotweed Control Program. The knotweed program met its goal of surveying and treating both the upper mainstem floodplains of the Sauk and Skagit Rivers. SFEG and WCC surveyed for knotweed in June and then implemented treatment from July until the first week of September. -

USGS Geologic Investigation Series I-2592, Pamphlet

GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE SAUK RIVER 30- BY 60-MINUTE QUADRANGLE, WASHINGTON By R.W. Tabor, D.B. Booth, J.A. Vance, and A.B. Ford But lower, in every dip and valley, the forest is dense, of trees crowded and hugely grown, impassable with undergrowth as toughly woven as a fisherman’s net. Here and there, unnoticed until you stumble across them, are crags and bouldered screes of rock thickly clothed with thorn and creeper, invisible and deadly as a wolf trap.1 The Hollow Hills by Mary Stewart, 1973 INTRODUCTION AND Ortenburger for office and laboratory services. R.W. Tabor ACKNOWLEDGMENTS prepared the digital version of this map with considerable help from Kris Alvarez, Kathleen Duggan, Tracy Felger, Eric When Russell (1900) visited Cascade Pass in 1898, he Lehmer, Paddy McCarthy, Geoffry Phelps, Kea Umstadt, Carl began a geologic exploration which would blossom only after Wentworth, and Karen Wheeler. three-quarters of a century of growing geologic theory. The Paleontologists who helped immensely by identifying region encompassed by the Sauk River quadrangle is so struc- deformed, commonly recrystallized, and usually uninspiring turally complex that when Misch (1952) and his students fossils are Charles Blome, William Elder, Anita Harris, David began their monumental studies of the North Cascades in L. Jones, Jack W. Miller, and Kate Schindler. Chuck Blome 1948, the available geologic tools and theories were barely has been particularly helpful (see table 1). adequate to start deciphering the history. Subsequently, Bryant We thank John Whetten, Bob Zartman, and John Stacey (1955), Danner (1957), Jones (1959), Vance (1957a), Ford and his staff for unpublished U-Pb isotopic analyses (cited (1959), and Tabor (1961) sketched the fundamental outlines of in table 2). -

Snohomish County Hiking Guide

2015- 2016 TO OUTDOOR ADVENTURE! 30 GREAT HIKES • DRIVING DIRECTIONS MAPS • ACCOMMODATIONS • LOCAL RESOURCES photo by Scott Morris PB | www.snohomish.org www.snohomish.org | 1 SCTB Print - Hiking Guide Cover 5.5” x 8.5” - Full Color 5-2015 HIKE NAME 1 Hike subtitle ROUNDTRIP m ile ELEVATION GAIN m ile HIKING SEASON m ile MAP m ile NOTES m ile DRIVING DIRECTIONS m ile CONTACT INFO m ile Hard to imagine, but one of the finest beaches River Delta. A fairly large lagoon has developed on in all of Snohomish County is just minutes from the island where you can watch for sandpipers, downtown Everett! And this two mile long sandy osprey, kingfishers, herons, finches, ducks, and expanse was created by man, not nature. Beginning more. in the 1890s, the Army Corp of Engineers built a You won’t be able to walk around the island as the jetty just north of Port Gardiner—then commenced channel side contains no beach. But the beach to dredge a channel. The spoils along with silt and on Possession Sound is wide and smooth and you sedimentation from the Snohomish River eventually can easily walk 4 to 5 miles going from tip to tip. created an island. Sand accumulated from tidal Soak up views of the Olympic Mountains; Whidbey, influences, birds arrived and nested, and plants Camano, and Gedney Islands; and downtown Everett soon colonized the island. against a backdrop of Cascades Mountains. In the 1980s the Everett Parks and Recreation Department began providing passenger ferry service to the island. Over 50,000 folks visit this sandy gem each year. -

Sediment Load and Distribution in the Lower Skagit River, Skagit County, Washington

A Study by the U.S. Geological Survey Coastal Habitats in Puget Sound (CHIPS) Project Sediment Load and Distribution in the Lower Skagit River, Skagit County, Washington Scientific Investigations Report 2016–5106 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Front Cover: Downstream view of the Skagit River near Mount Vernon, Washington, September 28, 2012. Photograph by Eric Grossman, U.S. Geological Survey. Back Cover: Downstream view of the North Fork Skagit River at the bifurcation near Skagit City, Washington, September 14, 2012. Photograph by Eric Grossman, U.S. Geological Survey. Sediment Load and Distribution in the Lower Skagit River, Skagit County, Washington By Christopher A. Curran, Eric E. Grossman, Mark C. Mastin, and Raegan L. Huffman A Study by the U.S. Geological Survey Coastal Habitats in Puget Sound (CHIPS) Project Scientific Investigations Report 2016–5106 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

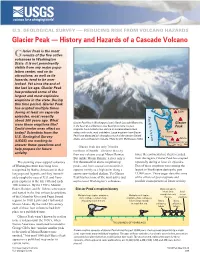

Glacier Peak — History and Hazards of a Cascade Volcano

USG S U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY — REDUCING RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS Glacier Peak — History and Hazards of a Cascade Volcano lacier Peak is the most Gremote of the five active volcanoes in Washington State. It is not prominently visible from any major popu- lation center, and so its attractions, as well as its hazards, tend to be over- looked. Yet since the end of the last ice age, Glacier Peak has produced some of the largest and most explosive eruptions in the state. During this time period, Glacier Peak has erupted multiple times during at least six separate Baker episodes, most recently Pacific Ocean about 300 years ago. What Glacier Peak lies in Washington State’s North Cascade Mountains, were these eruptions like? Glacier in the heart of a wilderness area bearing its name. Its past Peak Could similar ones affect us eruptions have melted snow and ice to inundate downstream today? Scientists from the valleys with rocks, mud, and debris. Large eruptions from Glacier Rainier U.S. Geological Survey Peak have deposited ash throughout much of the western United St. Helens States and southwestern Canada. Photo by D.R. Mullineaux, USGS. Adams (USGS) are working to WASHINGTON answer these questions and Glacier Peak lies only 70 miles help prepare for future northeast of Seattle—closer to that city activity. than any volcano except Mount Rainier. Since the continental ice sheets receded But unlike Mount Rainier, it rises only a from the region, Glacier Peak has erupted The stunning snow-capped volcanoes few thousand feet above neighboring repeatedly during at least six episodes.