Abstracts and Cvs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 12-26, 2019

JEWISH CONGREGATION OF NEW PALTZ PRESENTS theGLORY OF ISRAEL MAY 12-26, 2019 ramon crater tel aviv caesarea ariel sharon park jaffa SUNDAY, MAY 12 - Depart Newark with El Al nonstop flight #26 Visit Tel Aviv’s old city of Jaffa. Continue to the nearby, beautifully to Tel Aviv, leaving at 9:00pm. renovated Tahana (railroad station), with shops and cafes. MONDAY, MAY 13 - TEL AVIV (D) WEDNESDAY, MAY 15 - TEL AVIV (B) Upon arrival at Tel Aviv Ben Gurion Airport at 2:25pm, you will Visit the Ariel Sharon Park, one of the biggest environmental be met by a Ya’lla Tours USA Israel representative and transferred rehabilitation projects in the world. This once polluted land to your hotel for overnight. TAL BY THE BEACH is located just is now a flourishing park and the green lung of the country’s steps away from Metzizim Beach and Tel Aviv’s vibrant port, most densely populated urban region. Start with a short shopping, dining and nightlife areas. www.atlas.co.il/tal-hotel-tel-aviv lecture, followed by a film detailing the change from the Evening: dinner in one of Tel Aviv best restaurants on the beach. most famous garbage hill to a thriving modern green park. Drive to the Ayalon Institute, an underground ammunition TUESDAY, MAY 14 - TEL AVIV (B) factory that operated in 1948 in defiance of the British, You will be met in the hotel lobby by your private guide. Start your who prevented the Jews from buying or manufacturing tour today with an orientation tour of Tel Aviv, the largest and weapons in anticipation of the Arab invasion. -

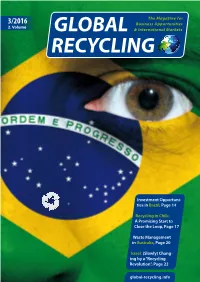

GLOBAL RECYCLING 3/2016 1 | This Issue

The Magazine for 3/2016 Business Opportunities 2. Volume GLOBAL & International Markets RECYCLING Investment Opportuni- ties in Brazil, Page 14 Recycling in Chile: A Promising Start to Close the Loop, Page 17 Waste Management in Australia, Page 20 Israel: (Slowly) Chang- ing by a “Recycling Revolution“, Page 23 global-recycling.info Editorial “Brexit“ and the Potential Implications GLOBAL RECYCLING The Magazine for Business Opportunities & International Markets Since the vote of the UK citizens to leave the European Union, the ‘Brexit’ was an important issue in the British, European ISSN-Print 2365-7928 and international waste and resource management indus- ISSN-Internet 2365-7936 try. You would almost think that the new government of the Publisher: United Kingdom is absolutely determined to implement this MSV Mediaservice & Verlag GmbH decision. If they realize this goal, there will be a huge uncer- Responsible for the Content: tainty in the future, according to experts. Oliver Kürth Editors: David Newman, President of ISWA (International Solid Waste Association), thinks Brigitte Weber (Editor-in-Chief) that Britain may become more isolated and return to the economic decline it had Tel.: +49 (0) 26 43 / 68 39 E-Mail: [email protected] before joining the EU. Furthermore, he sees the risk that some of the remaining countries also want to leave the EU. But there is another aspect: In waste and envi- Dr. Jürgen Kroll ronmental management, policies matter a lot. The industry is driven by regulations, Tel.: +49 (0) 51 51 / 86 92 E-Mail: [email protected] government intervention, government mandated taxation, targets, fines, penal- ties, enforcement. -

Rehabilitation of the Hiriya Landfill, Tel Aviv

Rehabilitation of the Hiriya Landfill, Tel Aviv Tilman Latz Latz + Partner Landscape Architecture Urban Planning, Kranzberg, Germany [email protected] ri-vista 01 2018 Abstract Hiriya, a closed domestic waste landfill, is situated on the wide river plain in the southeast of Tel Aviv. The impressive landmark is part of the future Ariel Sharon Park. It is getting rehabilitat- seconda serie ed since 2004. Aim is to preserve its captivating silhouette and to develop the landscape of and around the mountain by using construction techniques that take into consideration the waste tip’s instability and make use of local materials whilst incorporating the region’s traditional land uses and specific climatic conditions. The artificial appearance of the landscape and its origins become a part of a positive experience of the site – a convergence of nature and culture. Keywords Landfill Rehabilitation, Stormwater Retention, Resilient Park Landscape, Recycling & Educa- tion, Transformation Received: April 2018 / Accepted: April 2018 © The Author(s) 2018. This article is published with Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0 Firenze University Press. 54 DOI: 10.13128/RV-22991 - www.fupress.net/index.php/ri-vista/ Latz The Hiriya landfill, possibly the largest waste tip in through the centre of the city alongside which rail- the Near East, came to be in 1952 on the site of a way tracks and the Highway 1 and Highway 20 mo- Palestinian village abandoned in the Arab-Israe- torways were aligned. Due to extensive soil sealing li War. It is situated on an agricultural plain in the and the resultant reduction of water retention ca- southeast of Tel Aviv and is encircled by the two pacity within the river catchment area as well as the rivers Ayalon and Shapirim (fig. -

Tourism in Tel Aviv Vision and Master Plan

2030TOURISM IN TEL AVIV VISION AND MASTER PLAN Mayor: Ron Huldai Mina Ganem –Senior Division Head for Strategic Planning and Director General: Menahem Leiba Policy, Ministry of Tourism Deputy Director General and Head of Operations: Rubi Zluf Alon Sapan – Director, Natural History Museum Deputy Director General of Planning, Organization and Shai Deutsch – Marketing Director, Arcadia Information Systems: Eran Avrahami Daphne Schiller – Tel Aviv University Deputy Director General of Human Resources: Avi Peretz Shana Krakowski – Director, Microfy Eviatar Gover – Tourism Entrepreneur Tourism in Tel Aviv 2030 is the Master Plan for tourism in Uri Douek – Traveltech Entrepreneur the city, which is derived from the City Vision released by the Lilach Zioni – Hotel Management Student Municipality in 2017. The Master Plan was formulated by Tel Yossi Falach –Lifeguard Station Manager, Tel Aviv Aviv Global & Tourism and the Strategic Planning Unit at the Leon Avigad – Owner, Brown Hotels Company Tel Aviv Municipality. Gannit Mayslits-Kassif – Architect and City Planner The Plan was written by two consulting firms, Matrix Dr. Avi Sasson – Professor of Israel Studies, Ashkelon College and AZIC, and facilitated by an advisory committee of Shiri Meir – Booking.com Representative professionals from the tourism industry. We wish to take this Yoram Blumenkranz – Artist opportunity to thank all our partners. Imri Galai – Airbnb Representative Tali Ginot –The David Intercontinental Hotel, Tel Aviv Tel Aviv Global & Tourism - Eytan Schwartz - CEO, Lior Meyer, -

Oregoninnovators

NOVEMBER 2012 SERVING OREGON AND SW WASHINGTON Special SectionS JewiSh professionalS LAWYERS, DOCTORS ... ASTRONAUTS? S eniorS GREAT OPTIONS FOR THE GOLDEN YEARS oreGon innoVATORS NATIONAL FELLOWSHIP RECIPIENTS SARAH BLATTNER & STEVE EISENBACH-BUDNER JewiSh Book Month A REAL PAGE TURNER Turning 65 and have questions about Medicare? • What are my options? • Which plan is right for me? • Which company will best meet my needs? • How do I choose? Humana can help. We offer a variety of Medicare health plans and the experience to help you find the right Humana plan that meets your needs. Humana has been serving people just like you for over 50 years. We provide Medicare health plans, including prescription drug plans, to more than 4 million people across the country. Let’s talk. TO ARRANGE A PERSONAL APPOINTMENT, PLEASE CA.LL US TODAY 1-800-537-3692 (TTY: 711) 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., seven days a week Humana is a Medicare Advantage organization with a Medicare contract. Y0040_GHHHCZTHH CMS Accepted TRUSTWORTHY COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTIONS Contact Gretchen today for your one hour free consultation GRETCHEN STANGIER, CFP® WWW.STANGIERWEALTHMANAGEMENT.COM 9955 SE WASHINGTON, SUITE 101 • PORTLAND, OR 97216 • TOLL FREE 877-257-0057 • [email protected] Securities and advisory services offered through lpl financial. a registered investment advisor. Member finra/sipc. Bugatti’s Ristoranté - Bugatti’s Ristoranté serving West Linn lunch beginning mid November Mon - Sun 11:30a - 2p Happy Hour 4p - 6p & 8p-Close Dinner 5p daily crisp pear salad RISTORANTÉ -

Spot - English

SPOT - ENGLISH About Us We provide our clients with decades of experience in the fields of media relations consulting, communications and strategic advice in the highest levels. Spot Communications and Strategy (www.spotpr.co.il) is a leading strategic and media consultancy firm, dealing in tourism, leisure, culture and commerce. Our thorough knowledge of the media in these fields, enables us to provide accurate and targeted services to our clients. The team at Spot PR has years of experience and vast knowledge in accompanying decision making processes, in instigating and implementing strategic plans. Spot PR’s team is experienced in consulting to leading public and private organizations holding leading positions as spokespersons in the organizations. Spot Communications and Strategy provides its clients with a broad and comprehensive services package, including: building a media strategy, spokesmanship and public relations services, media relations consultancy, social networking, campaign management and crisis management. In addition, we offer our clientele graphic services as well as provide acquisition services of media and other additional services in the communications and media fields, both within the office and by cooperating with other professionals. Each client receives a tailored services package, designed to match their specific needs. We are committed in offering each and every client the most suitable frame of activities. Spot PR offers entrepreneurship, innovative, creative and “out of the box” thinking, while remaining totally committed to our clients. Together, we will determine where you want to go, and find the way to get you there. Our Team Lior Rotbart, Partner. Specializes in strategic media consulting, consulting to clients in the tourism and commerce industry; in managing political and educational campaigns. -

803ECE CECI CONF.10 2.Pdf

United Nations ECE/CECI/CONF.10/2 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 13 September 2011 Original: English Economic Commission for Europe Committee on Economic Cooperation and Integration International Conference "Promoting Eco-innovation: Policies and Opportunities" Tel Aviv, Israel, 11-13 July 2011 Report on the International Conference "Promoting Eco- innovation: Policies and Opportunities" I. Format and attendance 1. The International Conference "Promoting Eco-innovation: Policies and Opportunities" was held in Tel Aviv from 11 to 13 July 2011, in response to a proposal by the Government of Israel. This activity was in line with the Programme of Work for 2011 of the Committee on Economic Cooperation and Integration (CECI) of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), which was adopted at the fifth session of CECI held on 1-3 December 2010. The Conference was organized in cooperation with the Prime Minister's Office and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the State of Israel. 2. The main objective of the International Conference was to provide a platform for a discussion and broad exchange of experiences and lessons learned among policymakers, representatives of business and academia and other experts and practitioners. Participants considered how innovation policies can contribute to address environmental and energy challenges, the existing barriers for eco-innovation and the ways in which the public and private sectors can collaborate to overcome these difficulties and to take advantage of emerging opportunities in this area. 3. The main outcomes of the Conference will be used as an input to the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), which will take place in Brazil on 4-6 June 2012. -

Funding Environmental Stewardship in Israel

GREENBOOK A Guide to Intelligent Giving Volume 3 June 2015 Funding Environmental Stewardship in Israel WRITTEN BY AMIT ASHKENAZY & TZRUYA CALVÃO CHEBACH Funding Environmental Stewardship in Israel WRITTEN BY AMIT ASHKENAZY & TZRUYA CALVÃO CHEBACH Greenbooks are research reports written specifically for the funding community. Each unbiased, comprehensive guide focuses on a problem currently facing the Jewish community, maps out the relevant history, and details a wide range of approaches being taken to address the problem. Greenbooks are produced by the Jewish Funders Network, with a target publication of two guides annually. Greenbooks are available for download at www.jfunders.org/Greenbooks. www.jfunders.org For all of its geographical beauty and diversity, Israel is beset by constant pressure to safeguard its environment. How best to do so raises critical questions about the country’s evolving relationship to sustainability and social justice. Over the past two decades, philanthropic foundations—in partnership with civil society—have been instrumental in forging a vision of social environmental change in Israel, and in dramatically raising public awareness of environmental concerns. Looking at the emerging social environmental field today, it is clear that investing in the environment is no longer about nature conservation alone, but more broadly about investing in social justice, equality, education, and societal- environmental health. This shift has opened up wide channels in philanthropic potential. To mention just a few: Environmental concerns bring together people from a wide spectrum of Israeli society: Jews and Arabs, religious and secular, wealthy and poor, young and old. Addressing those concerns, therefore, can serve to bridge gaps in Israeli society. -

Ri-Vista 2018 Ricerche Per La Progettazione Del Paesaggio Seconda Serie

Special Issue 01 OUT OF WASTE LANDSCAPES ri-vista 2018 Ricerche per la progettazione del paesaggio seconda serie FIRENZE UNIVERSITY PRESS ri-vista Ricerche per la progettazione del paesaggio Rivista scientifica digitale semestrale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze seconda serie Research for landscape planning Digital semi-annual scientific journal University of Florence second series Fondatore Giulio G. Rizzo Direttori scientifici I serie Giulio G. Rizzo (2003-2008) Gabriele Corsani (2009-2014) Anno XVI n. 1/2018 Direttore responsabile II serie Registrazione Tribunale di Firenze Saverio Mecca n. 5307 del 10.11.2003 Direttore scientifico II serie Gabriele Paolinelli ISSN 1724-6768 COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Daniela Colafranceschi (Italia) Hassan Laghai (Iran) Christine Dalnoky (France) Jean Paul Métailié (France) Fabio Di Carlo (Italia) Valerio Morabito (Italia / USA) Pompeo Fabbri (Italia) Carlo Natali (Italia) Enrico Falqui (Italia) Carlo Peraboni (Italia) Roberto Gambino (Italia) Maria Cristina Treu (Italia) Gert Groening (Germany) Kongjian Yu (Cina) REDAZIONE Associate Editors: Claudia Cassatella, Anna Lambertini, Tessa Matteini, Emanuela Morelli, Section Editors: Debora Agostini, Enrica Campus, Sara Caramaschi, Gabriele Corsani, Elisabetta Maino, Ludovica Marinaro, Emma Salizzoni, Antonella Valentini Managing Editor: Michela Moretti CONTATTI Ri-Vista. Ricerche per la progettazione del paesaggio on-line: www.fupress.net/index.php/ri-vista/ [email protected] Ri-Vista, Dipartimento di Architettura Via della Mattonaia 14, 50121, Firenze in copertina The landscape of waste. © The Author(s) 2018. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0). If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original (CC BY-SA 4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode). -

Ecology, Environment, Sustainability: the Development of the Environmental Movement in Israel1

Cultural and Religious Studies, April 2016, Vol. 4, No. 4, 238-253 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2016.04.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Ecology, Environment, Sustainability: The Development of the Environmental Movement in Israel1 Benny Furst Ministry of Environmental Protection, Jerusalem, Israel The article surveys the development of the environmental movement in Israel from the establishment of the state through the present day. Based on trends and transformations in the institutional planning system, it appears that activism by environmental movement organizations in Israel can be divided into three sub-periods: the establishment period, marked by the Sharon Plan, the founding of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel and MALRAZ—Council for the Prevention of Noise and Air Pollution in Israel, and the enactment of the Kanovitch Law and the National Parks and Nature Reserves Law (1963). The next phase of institutionalization is characterized by the establishment of designated institutional bodies—the Nature Reserves Authority, the National Parks Authority and the Environmental Protection Service, and their integration into the national planning system. The institutionalization period concludes with the establishment of the Ministry of the Environment (1989) and the transition to the third period, sustainability. Prominent during this period is a trend toward multidimensional proactive environmental planning and policymaking, reaching across many areas and including extensive regulation. As far as environmental organizations are concerned, these three periods comprised a framework of cultural action in which they developed, acted and shaped environmental discourse and practice in Israel. Based on other studies, the article offers a model that illustrates the development of the environmental movement while emphasizing the interaction between individual actors, local organizing and national organizations. -

Mogućnosti Prenamjene Prostora Jakuševca Nakon Zatvaranja Odlagališta Otpada

SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU AGRONOMSKI FAKULTET MOGUĆNOSTI PRENAMJENE PROSTORA JAKUŠEVCA NAKON ZATVARANJA ODLAGALIŠTA OTPADA DIPLOMSKI RAD Beatrica Perkec Zagreb, listopad, 2018. SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU AGRONOMSKI FAKULTET Diplomski studij: Krajobrazna arhitektura MOGUĆNOSTI PRENAMJENE PROSTORA JAKUŠEVCA NAKON ZATVARANJA ODLAGALIŠTA OTPADA DIPLOMSKI RAD Beatrica Perkec Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Iva Rechner Dika Zagreb, listopad, 2018. SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU AGRONOMSKI FAKULTET IZJAVA STUDENTA O AKADEMSKOJ ČESTITOSTI Ja, Beatrica Perkec, JMBAG 0178089860, rođen/a dana 06.03.1993. u Virovitici, izjavljujem da sam samostalno izradila/izradio diplomski rad pod naslovom: MOGUĆNOSTI PRENAMJENE PROSTORA JAKUŠEVCA NAKON ZATVARANJA ODLAGALIŠTA OTPADA Svojim potpisom jamčim: da sam jedina autorica/jedini autor ovoga diplomskog rada; da su svi korišteni izvori literature, kako objavljeni tako i neobjavljeni, adekvatno citirani ili parafrazirani, te popisani u literaturi na kraju rada; da ovaj diplomski rad ne sadrži dijelove radova predanih na Agronomskom fakultetu ili drugim ustanovama visokog obrazovanja radi završetka sveučilišnog ili stručnog studija; da je elektronička verzija ovoga diplomskog rada identična tiskanoj koju je odobrio mentor; da sam upoznata/upoznat s odredbama Etičkog kodeksa Sveučilišta u Zagrebu (Čl. 19). U Zagrebu, dana _______________ ______________________ Potpis studenta / studentice SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU AGRONOMSKI FAKULTET IZVJEŠĆE O OCJENI I OBRANI DIPLOMSKOG RADA Diplomski rad studenta/ice Beatrice Perkec, JMBAG 0178089860, naslova MOGUĆNOSTI PRENAMJENE PROSTORA JAKUŠEVCA NAKON ZATVARANJA ODLAGALIŠTA OTPADA obranjen je i ocijenjen ocjenom ___________________ , dana _______________ . Povjerenstvo: potpisi: 1. doc. dr. sc. Iva Rechner Dika ____________________ 2. Izv. prof. art. Stanko Stergaršek, dipl. ing. arh. ____________________ 3. doc. dr. sc. Petra Pereković ____________________ Zahvaljujem mentorici doc.dr.sc. Ivi Rechner Diki na inspiraciji, sugestijama i svim konstruktivnim kritikama kojima me potakla da ovaj rad učinim što boljim. -

INTEGRATING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING and LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE to FACILITATE ENGAGEMENT and AWARENESS of WASTE LANDSCAPES by YING

INTEGRATING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE TO FACILITATE ENGAGEMENT AND AWARENESS OF WASTE LANDSCAPES by YING CHEN (Under the Direction of Douglas Pardue) ABSTRACT This thesis examines the potential role that landscape architects can play in increasing awareness of waste practices from experiential learning perspectives. My research question asks, how can landscape architecture facilitate experiential learning in waste landscapes? Facing the great waste challenges around urban areas, people start to realize that waste has become an inevitable part of our lives. For the purpose of increasing understanding of waste and engagement in waste landscapes, landscape architecture design is applied to create an integrated design framework with experiential learning. Following case studies and the literature review, a discussion about the availability of conceptual design approaches will take place. INDEX WORDS: Waste, Waste landscape, Landscape architecture, Experiential learning, Experiential learning space, Landscape engagement INTEGRATING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE TO FACILITATE ENGAGEMENT AND AWARENESS OF WASTE LANDSCAPES by YING CHEN Bachelor of Landscape Architecture, Southwest University, 2009 Master of Landscape Architecture, Nanjing Forestry University, 2013 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 YING CHEN All Rights Reserved INTEGRATING EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING AND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE TO FACILITATE ENGAGEMENT AND AWARENESS OF WASTE LANDSCAPES by YING CHEN Major Professor: Douglas Pardue Committee: Katherine Melcher Pratt Cassity Suki Janssen Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2017 DEDICATION I dedicated my thesis to my parents, who give incredible love and support all the way of my life, and many friends who have constantly encouraged me throughout this process.