= "SUPPOSENOBODYCARED" a Suppose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poems About Poets

1 BYRON’S POEMS ABOUT POETS Some of the funniest of Byron’s poems spring with seeming spontaneity from his pen in the middle of his letters. Much of this section comes from correspondence, though there is some formal verse. Several pieces are parodies, some one-off squibs, some full-length. Byron’s distaste for most of the poets of his day shines through, with the recurrent and well-worn traditional joke that their books will end either as stuffing in hatshops, wrapped around pastries, or as toilet-tissue. Byron admired the English poets of the past – the Augustans especially – much more than he did any of his contemporaries. Of “the Romantic Movement” he knew no more than did any of the other writers supposed now to have been members of it. Southey he loathed, as a dreadful doppelgänger – see below. Of Wordsworth he also had a low opinion, based largely on The Excursion – to the ambitions of which Don Juan can be regarded as a riposte (there are as many negative comments about Wordsworth in Don Juan as there are about Southey). He was as abusive of Keats as it’s possible to be, and only relented (as he said), when Shelley showed him Hyperion. Of the poetry of his friend Shelley he was very guarded indeed, and compensated by defending Shelley’s moral reputation. Blake he seems not to have known (“Blake” was him the name of a well-known Fleet Street barber). The only poet of whom his judgement and modern estimate coincide is Coleridge: he was strong in his admiration for The Ancient Mariner, Kubla Khan, and Christabel; about the conversational poems he seems blank, and he feigns total incomprehension of the Biographia Literaria (see below). -

Blue Banner Faith and Life

BLUE BANNER FAITH AND LIFE J. G. VOS, Editor and Manager Copyright © 2016 The Board of Education and Publication of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America (Crown & Covenant Publications) 7408 Penn Avenue • Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15208 All rights are reserved by the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America and its Board of Education & Publication (Crown & Covenant Publications). Except for personal use of one digital copy by the user, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. This project is made possible by the History Committee of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America (rparchives.org). BLUE BANNER FAITH AND LIFE VOLUME 9 JANUARY-MARCH, 1954 NUMBER 1 “A wonderful and horrible thing is committed in the land; the prophets prophesy falsely, and the priests bear rule by their means; and my people love to have it so: and what will ye do in the end thereof?” Jeremiah 5:30,31 A Quarterly Publication Devoted to Expounding, Defending and Applying the System of Doctrine set forth in the Word of God and Summarized in the Standards of the Reformed Presbyterian (Covenanter) Church. Subscription $1.50 per year postpaid anywhere J. G. Vos, Editor and Manager Route 1 Clay Center, Kansas, U.S.A. Editorial Committee: M. W. Dougherty, R, W. Caskey, Ross Latimer Published by The Board of Publication of the Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America Agent for Britain and Ireland: The Rev. -

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 a Sermon Preached Before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 A sermon preached before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26. of November, 1645 / by Jer.Burroughus. - London : printed for R.Dawlman, 1646. -[6],48p.; 4to, dedn. - Final leaf lacking. Bound with r the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S. SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 438 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons assembled in Parliament at their publique thanksgiving September 7 1641 for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. - [8],64p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : Gauden, J. The love of truth and peace. London, 1641. 1S.SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons, September 7.1641, for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. - London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. -[8],54p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S.SERMONS BURT, Edward, fl.1755 D 695-6 Letters from a gentleman in the north of Scotland to his friend in London : containing the description of a capital town in that northern country, likewise an account of the Highlands. - A new edition, with notes. - London : Gale, Curtis & Fenner, 1815. - 2v. (xxviii, 273p. : xii,321p.); 22cm. - Inscribed "Caledonian Literary Society." 2.A GENTLEMAN in the north of Scotland. 3S.SCOTLAND - Description and travel I BURTON, Henry, 1578-1648 K 140 The bateing of the Popes bull] / [by HenRy Burton], - [London?], [ 164-?]. -

Religious Leaders and Thinkers, 1516-1922

Religious Leaders and Thinkers, 1516-1922 Title Author Year Published Language General Subject A Biographical Dictionary of Freethinkers of All Ages and Nations Wheeler, J. M. (Joseph Mazzini); 1850-1898. 1889 English Rationalists A Biographical Memoir of Samuel Hartlib: Milton's Familiar Friend: With Bibliographical Notices of Works Dircks, Henry; 1806-1873. 1865 English Hartlib, Samuel Published by Him: And a Reprint of His Pamphlet, Entitled "an Invention of Engines of Motion" A Boy's Religion: From Memory Jones, Rufus Matthew; 1863-1948. 1902 English Jones, Rufus Matthew A Brief History of the Christian Church Leonard, William A. (William Andrew); 1848-1930. 1910 English Church history A Brief Sketch of the Waldenses Strong, C. H. 1893 English Waldenses A Bundle of Memories Holland, Henry Scott; 1847-1918. 1915 English Great Britain A Chapter in the History of the Theological Institute of Connecticut or Hartford Theological Seminary 1879 English Childs, Thomas S A Christian Hero: Life of Rev. William Cassidy Simpson, A. B. (Albert Benjamin); 1843-1919. 1888 English Cassidy, William A Church History for the Use of Schools and Colleges Lòvgren, Nils; b. 1852. 1906 English Church history A Church History of the First Three Centuries: From the Thirtieth to the Three Hundred and Twenty-Third Mahan, Milo; 1819-1870. 1860 English Church history Year of the Christian Era A Church History. to the Council of Nicaea A.D. 325 Wordsworth, Christopher; 1807-1885. 1892 English Church history A Church History. Vol. II; From the Council of Nicaea to That of Constantinople, A.D. 381 Wordsworth, Christopher; 1807-1885. 1892 English Church history A Church History. -

Francis Cranmer Penrose

FRANCIS CRANMER PENROSE 1817 – 1903 Architect of St Helen’s Church, Escrick J. P. G. Taylor 2018 FRANCIS CRANMER PENROSE 1817 – 1903 Architect of St Helen’s Church, Escrick Escrick enjoys the unusual, perhaps unique, distinction amongst English villages of having had three parish churches on different sites in the course of three-quarters of a century. The first was the Romanesque and Gothic church which stood close to the manor house in the centre of the old village at the top of the moraine and which served the parish for at least six hundred years. The second, the work of John Carr of York, succeeded the medieval church in the 1780s. Its site was a little to the west of the present third church which was consecrated in 1857 and was designed by the subject of this essay, Francis Cranmer Penrose. There would have been a small number of parishioners who knew all three churches. It is in fact quite possible that there were a few who were christened in the medieval church, married in the Georgian church and buried in the Victorian one. In the margin of the parish register for burials for 1857 - when the Victorian church must have been nearing completion - against the name of Ann Carr, widow, who died aged 90 on 18 January, the Rev Stephen Lawley, occupant of the new Penrose vicarage, has written in his neat hand: She could recollect the old Church wh was removed by the Act of Parl. in 17—1 by B Thompson esq. Almost nothing remains of the two earlier churches, the third happily survives, an unmissable landmark on the York/Selby road, to outward appearance much as F C Penrose would have known it more than a hundred and fifty years ago, though internally, thanks largely to a devastating fire in 1923, much changed. -

Affiliate Program-Middle School Flyer.Indd

Teachers COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS INITIATIVE Catalog EXEMPLAR TEXTS • MIDDLE SCHOOL EDITION • www.doverpublications.com Fall 2013 The World’s Greatest Literature for Your Middle School Classroom The Dover Book Club Great Books for Children, Valuable Rewards for Their School ith the Dover Book Club, you can access a huge Teachers can then use the rewards for discounts on Common Wselection of educational and entertaining books at Core State Standards exemplar texts, classic literature and affordable prices as you help your child’s school save on poetry, and thousands of other outstanding books. high-quality learning materials. This special collection includes a hand-picked selection of When you use the shopping link provided by your child’s Dover bestsellers for your child — you can choose from over teacher, every Dover order you place earns a classroom 10,000 more titles at our website. Please remember, you must reward equal to 25% of the purchase value. use your teacher’s exclusive shopping link when ordering. Welcome to the Dover Book Club. We hope that you fi nd it a rewarding experience! Common Core Standards: The Common Core State Standards Initiative is a state-led effort coordinated by the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The standards were developed in collaboration with teachers, school administrators, and experts to provide a clear and consistent framework to prepare our children for college and the workforce. Dover is proud to offer a wide variety of the exemplar texts chosen by the NGA and CCSSO, many of which can be found below and on page 3. -

Literary Deans Transcript

Literary Deans Transcript Date: Wednesday, 21 May 2008 - 12:00AM LITERARY DEANS Professor Tim Connell [PIC1 St Paul's today] Good evening and welcome to Gresham College. My lecture this evening is part of the commemoration of the tercentenary of the topping-out of St Paul's Cathedral.[1] Strictly speaking, work began in 1675 and ended in 1710, though there are those who probably feel that the task is never-ending, as you will see if you go onto the website and look at the range of work which is currently in hand. Those of you who take the Number 4 bus will also be aware of the current fleeting opportunity to admire the East end of the building following the demolition of Lloyd's bank at the top of Cheapside. This Autumn there will be a very special event, with words being projected at night onto the dome. [2] Not, unfortunately, the text of this lecture, which is, of course, available on-line. So why St Paul's? Partly because it dominates London, it is a favourite landmark for Londoners, and an icon for the City. [PIC2 St Paul's at War] It is especially significant for my parents' generation as a symbol of resistance in wartime, and apart from anything else, it is a magnificent structure. But it is not simply a building, or even (as he wished) a monument to its designer Sir Christopher Wren, who was of course a Gresham Professor and who therefore deserved no less. St Paul's has been at the heart of intellectual and spiritual life of London since its foundation 1400 years ago. -

Alt Context 1861-1896

1861 – Context – 168 Agnes Martin; or, the fall of Cardinal Wolsey. / Martin, Agnes.-- 8o..-- London, Oxford [printed], [1861]. Held by: British Library The Agriculture of Berkshire. / Clutterbuck, James Charles.-- pp. 44. ; 8o..-- London; Slatter & Rose: Oxford : Weale; Bell & Daldy, 1861. Held by: British Library Analysis of the history of England, (from William Ist to Henry VIIth,) with references to Hallam, Guizot, Gibbon, Blackstone, &c., and a series of questions / Fitz-Wygram, Loftus, S.C.L.-- Second ed.-- 12mo.-- Oxford, 1861 Held by: National Library of Scotland An Answer to F. Temple's Essay on "the Education of the World." By a Working Man. / Temple, Frederick, Successively Bishop of Exeter and of London, and Archbishop of Canterbury.-- 12o..-- Oxford, 1861. Held by: British Library Answer to Professor Stanley's strictures / Pusey, E. B. (Edward Bouverie), 1800-1882.-- 6 p ; 22 cm.-- [Oxford] : [s.n.], [1861] Notes: Caption title.-- Signed: E.B. Pusey Held by: Oxford Are Brutes immortal? An enquiry, conducted mainly by the light of nature into Bishop Butler's hypotheses and concessions on the subject, as given in part 1. chap. 1. of his "Analogy of Religion." / Boyce, John Cox ; Butler, Joseph, successively Bishop of Bristol and of Durham.-- pp. 70. ; 8o..-- Oxford; Thomas Turner: Boroughbridge : J. H. & J. Parker, 1861. Held by: British Library Aristophanous Ippes. The Knights of Aristophanes / with short English notes [by D.W. Turner] for the use of schools.-- 56, 58 p ; 16mo.-- Oxford, 1861 Held by: National Library of Scotland Arnold Prize Essay, 1861. The Christians in Rome during the first three centuries. -

![The History of the Jews [By H.H. Milman]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7394/the-history-of-the-jews-by-h-h-milman-5117394.webp)

The History of the Jews [By H.H. Milman]

r-He weLL read mason li""-I:~I=-•I cl••'ILei,=:-,•• Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Literature, Religion, and Postsecular Studies Lori Branch, Series Editor Joanna Southcott (1812)

Literature, Religion, and Postsecular Studies Lori Branch, Series Editor Joanna Southcott (1812). Engraving by William Sharp © Trustees of the British Museum AKE L ETHODISM Polite LiteratureM and Popular Religion in England, 1780–1830 JASPER CRAGWALL THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2013 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cragwall, Jasper Albert, 1977– Lake Methodism : polite literature and popular religion in England, 1780–1830 / Jasper Cragwall. p. cm. (Literature, religion, and postsecular studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1227-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1227-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9329-4 (cd) 1. English literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Religion and literature—Great Britain—History—19th century. 3. English literature—18th century—History and criticism. 4. Religion and literature—Great Britain—History—18th century. 5. Romanticism—Great Britain. 6. Methodism in literature. 7. Methodism—History. 8. Methodism—Influence. 9. Great Brit- ain—Intellectual life—19th century. 10. Great Britain—Intellectual life—18th century. I. Title. II. Series: Literature, religion, and postsecular studies. PR468.R44C73 2013 820.9'382—dc23 2013004710 Cover design by Juliet Williams Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Sabon Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence -

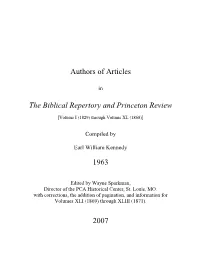

Authors of Articles in the Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review

Authors of Articles in The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review [Volume I (1829) through Volume XL (1868)] Compiled by Earl William Kennedy 1963 Edited by Wayne Sparkman, Director of the PCA Historical Center, St. Louis, MO. with corrections, the addition of pagination, and information for Volumes XLI (1869) through XLIII (1871). 2007 INTRODUCTION This compilation is designed to make possible the immediate identification of the author(s) of any given article (or articles) in the Princeton Review. Unless otherwise stated, it is based on the alphabetical list of authors in the Index Volume from 1825 to 1868 (published in 1871), where each author‘s articles are arranged chronologically under his name. This Index Volume list in turn is based upon the recollections of several men closely associated with the Review. The following account is given of its genesis: ―Like the other great Reviews of the periods the writers contributed to its pages anonymously, and for many years no one kept any account of their labours. Dr. [Matthew B.] Hope [died 1859] was the first who attempted to ascertain the names of the writers in the early volumes, and he was only partially successful. With the aid of his notes, and the assistance of Dr. John Hall of Trenton, Dr. John C. Backus of Baltimore, and Dr. Samuel D. Alexander of New York, the companions and friends of the Editor and his early coadjutors, the information on this head here collected is as complete as it is possible now to be given.‖ (Index Volume, iii; of LSM, II, 271n; for meaning of symbols, see below) The Index Volume is usually but not always reliable. -

Miller Collection Thurso Main Title Personal Author Date BRN Handbook of the History of Philosophy / by Dr

Miller Collection Thurso Main Title Personal Author Date BRN Handbook of the History of Philosophy / by Dr. Albert Schwegler and Translated and annotatedSchwegler, by Friedrich James Hutchinson Carl Albert; Stirling. Stirling, James Hutchison, 1820-19091888 1651588 An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations / by Adam Smith. Smith, Adam, 1723-1790; McCulloch, J. R. (John Ramsay), 1789-18641850 1651587 Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Vol. 1 / by John Wright and Edited by James E.Bright, Thorold John, Rogers. Right Hon; Rogers, James E. Thorold (James Edwin1869 Thorold),1651586 1823-1890 Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Vol. 2 / by John Wright and Edited by James E.Bright, Thorold John, Rogers. Right Hon; Rogers, James E. Thorold (James Edwin1869 Thorold),1651585 1823-1890 John Knox / by W.M. Taylor. Taylor, William M. (William Mackergo), 1829-1895; Knox, John,1884 ca. 1514-15721651584 Italian Pictures, drawn with pen and pencil / by Samuel Manning. Manning, Samuel, LL.D.; Green, Samuel Gosnell 1885 1651583 Morag: a tale of Highland life / by Mrs. Milne Rae. Rae, Milne, Mrs 1872 1650801 The Crossing / by Winston Churchill, with illustrations by Sydney Adamson and Lillian Bayliss.Churchill, Winston, 1871-1947 1924 1650800 Memoir of the Rev. Henry Martyn / by John Sargent. Sargent, John, Rector of Lavington 1820 1650799 Life of the late John Duncan, LL.D. [With a portrait.] / by David Brown. Brown, David, Principal of the Free Church College, Aberdeen 1872 1650798 On Teaching: its ends and means / by Henry Calderwood. Calderwood, Henry, L.L.D., F.R.S.E. 1881 1650797 Indian Polity: a view of the system of administration in India.