Servitude, Slavery, and Ideology in the 17Th-And 18Th-Century Anglo-American Atlantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

" Ht Tr H" : Trtp Nd N Nd Tnf P Rhtn Th

ht "ht Trh": trtp nd n ndtn f Pr ht n th .. nnl Ntz, tth r Minnesota Review, Number 47, Fall 1996 (New Series), pp. 57-72 (Article) Pblhd b D nvrt Pr For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mnr/summary/v047/47.newitz.html Access provided by Middlebury College (11 Dec 2015 16:54 GMT) Annalee Newitz and Matthew Wray What is "White Trash"? Stereotypes and Economic Conditions of Poor Whites in the U.S. "White trash" is, in many ways, the white Other. When we think about race in the U.S., oftentimes we find ourselves constrained by cat- egories we've inherited from a kind of essentialist multiculturalism, or what we call "vulgar multiculturalism."^ Vulgar multiculturalism holds that racial and ethic groups are "authentically" and essentially differ- ent from each other, and that racism is a one-way street: it proceeds out of whiteness to subjugate non-whiteness, so that all racists are white and all victims of racism are non-white. Critical multiculturalism, as it has been articulated by theorists such as those in the Chicago Cultural Studies Group, is one example of a multiculturalism which tries to com- plicate and trouble the dogmatic ways vulgar multiculturalism has un- derstood race, gender, and class identities. "White trash" identity is one we believe a critical multiculturalism should address in order to further its project of re-examining the relationships between identity and social power. Unlike the "whiteness" of vulgar multiculturalism, the whiteness of "white trash" signals something other than privilege and social power. -

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

DISENCHANTING the AMERICAN DREAM the Interplay of Spatial and Social Mobility Through Narrative Dynamic in Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Wolfe

DISENCHANTING THE AMERICAN DREAM The Interplay of Spatial and Social Mobility through Narrative Dynamic in Fitzgerald, Steinbeck and Wolfe Cleo Beth Theron Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr. Dawid de Villiers March 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this thesis/dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2013 Copyright © Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the long-established interrelation between spatial and social mobility in the American context, the result of the westward movement across the frontier that was seen as being attended by the promise of improving one’s social standing – the essence of the American Dream. The focal texts are F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and Thomas Wolfe’s You Can’t Go Home Again (1940), journey narratives that all present geographical relocation as necessary for social progression. In discussing the novels’ depictions of the itinerant characters’ attempts at attaining the American Dream, my study draws on Peter Brooks’s theory of narrative dynamic, a theory which contends that the plotting operation is a dynamic one that propels the narrative forward toward resolution, eliciting meanings through temporal progression. -

Chartrand Madeleine J O 201

Gendered Justice: Women Workers, Gender, and Master and Servant Law in England, 1700-1850 Madeleine Chartrand A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History York University Toronto, Ontario September 2017 © Madeleine Chartrand, 2017 ii Abstract As England industrialized in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, employment relationships continued to be governed, as they had been since the Middle Ages, by master and servant law. This dissertation is the first scholarly work to conduct an in-depth analysis of the role that gender played in shaping employment law. Through a qualitative and quantitative examination of statutes, high court rulings, and records of the routine administration of the law found in magistrates’ notebooks, petty sessions registers, and lists of inmates in houses of correction, the dissertation shows that gendered assumptions influenced the law in both theory and practice. A tension existed between the law’s roots in an ideology of separate spheres and the reality of its application, which included its targeted use to discipline a female workforce that was part of the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution. A close reading of the legislation and judges’ decisions demonstrates how an antipathy to the notion of women working was embedded in the law governing their employment relationships. An ideological association of men with productivity and women with domesticity underlay both the statutory language and key high court rulings. Therefore, although the law applied to workers of both sexes, women were excluded semantically, and to some extent substantively, from its provisions. -

Worcester Banner 12-1839.Pdf (3.937Mb)

" HE H THE FBBBMAN, WHOM THE TROTH MAKES FREE.'' VOL. It. SNOW-HILL, WORCESTER COtWVTF, MD. TUESDAY, DECEMBER 3rd. 1839 M III. *• WALTER? ned he.buried his roWels in his steed, and went had suddenly attacked the toWQruhe night be- ^ricd Agnes with clasped hands, as she, day wore on, and the sun wheeled his broad uir- TEAMS long the rocky road, followed by his fote, carried it by overwhelm" ^umbers,p|un- (caught fight of them,"there is the crest of Wal- co in the bosom of the. Rhine, lengthening the i:nd and-their followers pell-mel), their armor d>red, sacked, and tired it, 8?/'rv .~Ml mornir.g at ter, the very scarf I broiilercd for him,tho sainis shadows of ihe hills around/and burying the tORCEbTER BAM ,_ ibhctl «lll<fee dollar" Per *>n tied by ringing and<clashing,atid the fire Hying Inoin the dawn had departed, bearing oft '4th them their be praised lor his timely succor?' and unable to valhes in the gloom of twilight. The breeze fo,, and fifty cenn in rocks beneath their impalieni hoois. , booty, and carrying away (tie weeping Agues sustain her feelings, she fell buck almost fainting came damp frouHhe river, and the birds, re in advance, lor A few minutes continued their worst fears. ;and her hand-maid as prisoners,'i^terving them. against the ruinous wall. turning to their nests^ailed slowly by. I,, vain will be taken lor a- wiiinoflthBjarul no paper will As they gained the fool of the Ascent, which led for a fate more drcadlul (han even death itself. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

The Hardening Plight of the American Ex-Convict

WHEN THE PAST IS A PRISON: THE HARDENING PLIGHT OF THE AMERICAN EX-CONVICT Roger Roots University of Nevada, Las Vegas Department of Sociology ABSTRACT Today’s American criminal justice system is generating more ex-criminals than ever before, due to increasingly punitive sentencing, the increasing criminalization of formerly noncriminal acts, and the increasing federalization of criminal matters. At the same time, advances in record-keeping and computer technology have made life more difficult for ex-convicts. This article examines the hardships faced by American ex- convicts reentering the non-custodial community both at present and in the past. It concludes that modern ex-convicts face more difficulties than those of past generations, because 1) a greater number of laws that restrict their occupational and social lives, and 2) better data collection and transfer among criminal justice jurisdictions make evading or escaping from one’s criminal past more difficult. The result of these coalescing trends is that American society is increasingly forming a hierarchical order of citizenship, with long-term negative economic and social consequences for both ex-offenders and the broader community. 2 INTRODUCTION Criminal convictions have always carried collateral consequences in addition to their formal penalties. During much of American history—and, indeed, the history of the English legal system—convicted felons suffered a loss of social standing, disenfranchisement, and in some cases, “civil death,” a state in which they were denied all rights of citizenship including marriage, inheritance, and public office. In contrast, contemporary American ex-convicts retain their citizenship, their rights of property ownership, and their marriage and family rights, but are denied a host of other rights and privileges such as bearing arms and working in various occupations. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

1 1. Suppression of the Atlantic Slave Trade

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Leeds Beckett Repository 1. Suppression of the Atlantic slave trade: Abolition from ship to shore Robert Burroughs This study provides fresh perspectives on criticalaspects of the British Royal Navy’s suppression of the Atlantic slave trade. It is divided into three sections. The first, Policies, presents a new interpretation of the political framework underwhich slave-trade suppression was executed. Section II, Practices, examines details of the work of the navy’s West African Squadronwhich have been passed over in earlier narrativeaccounts. Section III, Representations, provides the first sustained discussion of the squadron’s wider, cultural significance, and its role in the shaping of geographical knowledge of West Africa.One of our objectives in looking across these three areas—a view from shore to ship and back again--is to understand better how they overlap. Our authors study the interconnections between political and legal decision-making, practical implementation, and cultural production and reception in an anti-slavery pursuit undertaken far from the metropolitan centres in which it was first conceived.Such an approachpromises new insights into what the anti-slave-trade patrols meant to Britain and what the campaign of ‘liberation’ meant for those enslaved Africans andnavalpersonnel, including black sailors, whose lives were most closely entangled in it. The following chapters reassess the policies, practices, and representations of slave- trade suppression by building upon developments in research in political, legal and humanitarian history, naval, imperial and maritime history, medical history, race relations and migration, abolitionist literature and art, nineteenth-century geography, nautical literature and art, and representations of Africa. -

A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries

History in the Making Volume 1 Article 7 2008 A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries Adam D. Wilsey CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Wilsey, Adam D. (2008) "A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries," History in the Making: Vol. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol1/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 78 CSUSB Journal of History A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries Adam D. Wiltsey Linschoten, South and West Africa, Copper engraving (Amsterdam, 1596.) Accompanying the dawn of the twenty‐first century, there has emerged a new era of historical thinking that has created the need to reexamine the history of slavery and slave resistance. Slavery has become a controversial topic that historians and scholars throughout the world are reevaluating. In this modern period, which is finally beginning to honor the ideas and ideals of equality, slavery is the black mark of our past; and the task now lies History in the Making 79 before the world to derive a better understanding of slavery. In order to better understand slavery, it is crucial to have a more acute awareness of those that endured it. -

Transportation from Britain and Ireland, 1615–1875." a Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish. "Transportation from Britain and Ireland, 1615–1875." A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies. Ed. Clare Anderson. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. 183–210. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350000704.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 20:57 UTC. Copyright © Clare Anderson and Contributors 2018. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 7 Transportation from Britain and Ireland, 1615–1875 Hamish Maxwell-Stewart Despite recent research which has revealed the extent to which penal transportation was employed as a labour mobilization device across the Western empires, the British remain the colonial power most associated with the practice.1 The role that convict transportation played in the British colonization of Australia is particularly well known. It should come as little surprise that the UNESCO World Heritage listing of places associated with the history of penal transportation is entirely restricted to Australian sites.2 The manner in which convict labour was utilized in the development of English (later British) overseas colonial concerns for the 170 years that proceeded the departure of the First Fleet for New South Wales in 1787 is comparatively neglected. There have been even fewer attempts to explain the rise and fall of transportation as a British institution from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. In part this is because the literature on British systems of punishment is dominated by the history of prisons and penitentiaries.3 As Braithwaite put it, the rise of prison has been ‘read as the enduring central question’, sideling examination of alternative measures for dealing with offenders. -

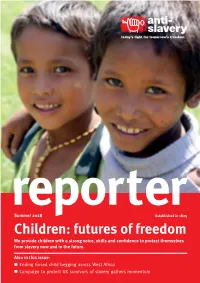

Reporter Magazine Was Our Vision Is a World Free from Slavery Seem Small Because of How Much There Established in 1825 and Has Is Left to Do

reporter Summer 2018 Established in 1825 Children: futures of freedom We provide children with a strong voice, skills and confidence to protect themselves from slavery now and in the future. Also in this issue: Ending forced child begging across West Africa Campaign to protect UK survivors of slavery gathers momentum reporter reporter summer 2018 summer 2018 2 comment 3 Tackling root causes for long term change I am delighted to introduce this issue of the Reporter for the first time as the new Chief Executive of Anti-Slavery International. Jasmine O’Connor Anti-Slavery’s work addresses not only immediate Chief Executive situations of exploitation, but tackles the roots causes. This is one of the reasons I am so excited about taking up this role. Nowhere is this approach more acute than in our work with children. We want children to have a strong voice, skills and confidence to be better equipped to protect themselves from exploitation now and in the future. You can read about how we work to achieve this in our features on pages 8 to 14. Young girls are commonly exploited in clothing Eradicating slavery is far from factories in India. simple. Sometimes the challenging Photo: Dev Gogoi circumstances in which we operate can We want children to have make even the most hard-fought wins a strong voice, skills and The Reporter magazine was Our vision is a world free from slavery seem small because of how much there established in 1825 and has is left to do. But every piece of progress confidence to be better been continuously published Anti-Slavery International works to eliminate we make, for example in protecting equipped to protect since 1840.