Chronic Cluster Headache with a Pediatric Onset: the First Japanese Case Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-(4-Amino-Cyclohexyl)

(19) & (11) EP 1 598 339 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 211/04 (2006.01) C07D 211/06 (2006.01) 24.06.2009 Bulletin 2009/26 C07D 235/24 (2006.01) C07D 413/04 (2006.01) C07D 235/26 (2006.01) C07D 401/04 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 05014116.7 C07D 401/06 C07D 403/04 C07D 403/06 (2006.01) A61K 31/44 (2006.01) A61K 31/48 (2006.01) A61K 31/415 (2006.01) (22) Date of filing: 18.04.2002 A61K 31/445 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) (54) 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE DERIVATIVES AND RELATED COMPOUNDS AS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGS AND ORL1 LIGANDS FOR THE TREATMENT OF PAIN 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ON DERIVATE UND VERWANDTE VERBINDUNGEN ALS NOCICEPTIN ANALOGE UND ORL1 LIGANDEN ZUR BEHANDLUNG VON SCHMERZ DERIVÉS DE LA 1-(4-AMINO-CYCLOHEXYL)-1,3-DIHYDRO-2H-BENZIMIDAZOLE-2-ONE ET COMPOSÉS SIMILAIRES POUR L’UTILISATION COMME ANALOGUES DU NOCICEPTIN ET LIGANDES DU ORL1 POUR LE TRAITEMENT DE LA DOULEUR (84) Designated Contracting States: • Victory, Sam AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU Oak Ridge, NC 27310 (US) MC NL PT SE TR • Whitehead, John Designated Extension States: Newtown, PA 18940 (US) AL LT LV MK RO SI (74) Representative: Maiwald, Walter (30) Priority: 18.04.2001 US 284666 P Maiwald Patentanwalts GmbH 18.04.2001 US 284667 P Elisenhof 18.04.2001 US 284668 P Elisenstrasse 3 18.04.2001 US 284669 P 80335 München (DE) (43) Date of publication of application: (56) References cited: 23.11.2005 Bulletin 2005/47 EP-A- 0 636 614 EP-A- 0 990 653 EP-A- 1 142 587 WO-A-00/06545 (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in WO-A-00/08013 WO-A-01/05770 accordance with Art. -

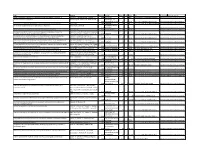

Preventive Report Appendix

Title Authors Published Journal Volume Issue Pages DOI Final Status Exclusion Reason Nasal sumatriptan is effective in treatment of migraine attacks in children: A Ahonen K.; Hamalainen ML.; Rantala H.; 2004 Neurology 62 6 883-7 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115105.05966.a7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Seasonal variation in migraine. Alstadhaug KB.; Salvesen R.; Bekkelund SI. Cephalalgia : an 2005 international journal 25 10 811-6 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01018.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Flunarizine, a calcium channel blocker: a new prophylactic drug in migraine. Amery WK. 1983 Headache 23 2 70-4 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1983.hed2302070 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the control of migraine. Anthony M.; Lance JW. Proceedings of the 1970 Australian 7 45-7 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Prostaglandins and prostaglandin receptor antagonism in migraine. Antonova M. 2013 Danish medical 60 5 B4635 Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex extended-release in adolescent migraine prophylaxis: results of a Apostol G.; Cady RK.; Laforet GA.; Robieson randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. WZ.; Olson E.; Abi-Saab WM.; Saltarelli M. 2008 Headache 48 7 1012-25 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01081.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Divalproex sodium extended-release for the prophylaxis of migraine headache in Apostol G.; Lewis DW.; Laforet GA.; adolescents: results of a stand-alone, long-term open-label safety study. Robieson WZ.; Fugate JM.; Abi-Saab WM.; 2009 Headache 49 1 45-53 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01279.x Deemed irrelevant in initial screening Safety and tolerability of divalproex sodium extended-release in the prophylaxis of Apostol G.; Pakalnis A.; Laforet GA.; migraine headaches: results of an open-label extension trial in adolescents. -

Sample Chapter from Martindale

670 Antimigraine Drugs Antimigraine Drugs periods. Other drugs under investigation include gabapen- 4. Anonymous. Management of medication overuse headache. Drug Ther Bull Cluster headache, p. 670 tin, melatonin, and topiramate.4,9-11,13 2010; 48: 2–6. 5. Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive acute migraine medication use and Medication-overuse headache, p. 670 Paroxysmal hemicrania is a rare variant of cluster migraine progression. Neurology 2008; 71: 1821–8. Migraine, p. 670 headache and differs mainly in the high frequency and 6. British Association for the Study of Headache. Guidelines for all Post-dural puncture headache, p. 671 shorter duration of individual attacks. One of its features, healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, which may be diagnostic, is its invariable response to tension-type, cluster and medication-overuse headache. 3rd edn. Tension-type headache, p. 671 (issued 18th January, 2007; 1st revision, September 2010). Available at: 10 indometacin. http://217.174.249.183/upload/NS_BASH/2010_BASH_Guidelines.pdf 1. Dodick DW, Capobianco DJ. Treatment and management of cluster (accessed 01/12/10) headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2001; 5: 83–91. 7. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Diagnosis and management This chapter reviews the management of headache, in 2. Zakrzewska JM. Cluster headache: review of literature. Br J Oral of headache in adults (issued November 2008). Available at: http:// particular migraine and cluster headache, and the drugs Maxillofac Surg 2001; 39: 103–13. www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign107.pdf (accessed 26/01/09) Drug Safety used mainly for their treatment. The mechanisms of head 3. Ekbom K, Hardebo JE. -

Calcium Channels As Novel Therapeutic Targets for Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Calcium Channels as Novel Therapeutic Targets for Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells 1,2, 1,2, 3, 1 1 Heejin Lee y , Jun Woo Kim y, Dae Kyung Kim y, Dong Kyu Choi , Seul Lee , Ji Hoon Yu 1,2, Oh-Bin Kwon 1, Jungsul Lee 4, Dong-Seok Lee 2,* , Jae Ho Kim 3,* and Sang-Hyun Min 1,* 1 New Drug Development Center, DGMIF, 80 Chumbok-ro, Dong-gu, Daegu 41061, Korea; [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (J.W.K.); [email protected] (D.K.C.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (J.H.Y.); [email protected] (O.-B.K.) 2 School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, BK21 Plus KNU Creative BioResearch Group, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 41566, Korea 3 Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Pusan National University, Yangsan 50612, Korea; [email protected] 4 3 billion Inc., Seocho-gu, Seoul 06621, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.-S.L.); [email protected] (J.H.K.); [email protected] (S.-H.M.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 5 March 2020; Accepted: 24 March 2020; Published: 27 March 2020 Abstract: Drug resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is reportedly attributed to the existence of cancer stem cells (CSC), because in most cancers, CSCs still remain after chemotherapy. To overcome this limitation, novel therapeutic strategies are required to prevent cancer recurrence and chemotherapy-resistant cancers by targeting cancer stem cells (CSCs). We screened an FDA-approved compound library and found four voltage-gated calcium channel blockers (manidipine, lacidipine, benidipine, and lomerizine) that target ovarian CSCs. -

Inhibitory Effect of Lomerizine, a Diphenylpiperazine Ca2+ -Channel Blocker, on Ba2+ Current Through Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channels in PC 12 Cells

Inhibitory Effect of Lomerizine, a Diphenylpiperazine Ca2+ -Channel Blocker, on Ba2+ Current through Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channels in PC 12 Cells Tomokazu Watanol, Hideaki Hara2,* and Takayuki Sukamoto2 1 Department of Pharmacology, New Drug Discovery Research Laboratory, Kanebo Ltd., 1-5-90 Tomobuchi-cho,of Pharmacology, Miyakojima-ku, New Drug Osaka R & 534,D Laboratory, Japan2Department Kanebo Ltd., 1-5-90 Tomobuchi-cho, Miyakojima-ku, Osaka 534, Japan Received July 8, 1997 Accepted August 22, 1997 ABSTRACT-We investigated the effect of lomerizine, an anti-migraine drug, on the Ba2+ current through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells using a whole-cell voltage-clamp tech nique. Lomerizine inhibited the Ba2+ current with an IC50 value of 1.9 ƒÊM. Lomerizine and nicardipine were > 4 times more potent than flunarizine, diltiazem, verapamil and dimetotiazine. The time course of inactivation induced by lomerizine was similar to that induced by nicardipine and flunarizine. These data indicate that lomerizine may inhibit the Ca2+ channel in a similar manner to nicardipine and flunarizine, and its potency is almost equal to that of nicardipine. Keywords: Lomerizine , Voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, PCl2 cell Calcium channel blockers are mainly divided into three Bio Medical, Kyoto) containing 7° fetal bovine serum types, namely, 1,4-dihydropyridine, phenylalkylamine (Moregate, Melbourne, Australia), 7% heat-inactivated and benzothiazepine types, from their structure (1). horse serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 2 MM L Lomerizine, 1-[bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-4-(2,3,4 glutamine (Wako, Osaka) and 50 pg/ml gentamicin sul trimethoxybenzyl)piperazine dihydrochloride has been fate (Wako) at 37C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. -

Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias CQ IV-1

IV Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias CQ IV-1 How are trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias classified and typed? Recommendation The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition (beta version; ICHD-3 beta) classifies cluster headache together with related diseases under “Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias”. Furthermore, “Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias” is further divided into five subtypes: cluster headache, paroxysmal hemicrania, short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks, hemicrania continua and probable trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia. Grade A Background and Objective The objective of this section is to classify Trigeminal“ autonomic cephalalgias” according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition (beta version; ICHD-3 beta).1)2) Comments and Evidence Cluster headache and related diseases are characterized by short-lasting, unilateral headache attacks accompanied by cranial parasympathetic autonomic symptoms including conjunctival injection, lacrimation, and rhinorrhea. These syndromes support the involvement of trigeminal-parasympathetic reflex activation, and ICHD-3 beta introduces the concept of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) (Table 1). TACs comprise the following subtypes: 3.1 cluster headache, 3.2 paroxysmal hemicrania, 3.3 short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks, 3.4 hemicrania continua, and 3.5 probable trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgia. Table 1. Classification of “3.Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias” 3.1 Cluster headache 3.1.1 Episodic cluster -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

Real World Effectiveness and Tolerability of Candesartan

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Real world efectiveness and tolerability of candesartan in the treatment of migraine: a retrospective cohort study Carmen Sánchez‑Rodríguez1, Álvaro Sierra2, Álvaro Planchuelo‑Gómez3, Enrique Martínez‑Pías2, Ángel L. Guerrero1,2,4* & David García‑Azorín2,4 To date, two randomized, controlled studies support the use of candesartan for migraine prophylaxis but with limited external validity. We aim to evaluate the efectiveness and tolerability of candesartan in clinical practice and to explore predictors of patient response. Retrospective cohort study including all patients with migraine who received candesartan between April 2008‑February 2019. The primary endpoint was the number of monthly headache days during weeks 8–12 of treatment compared to baseline. Additionally, we evaluated the frequency during weeks 20–24. We analysed the percentage of patients with 50% and 75% response rates and the retention rates after three and 6 months of treatment. 120/4121 patients were eligible, aged 45.9 [11.5]; 100 (83.3%) female. Eighty‑four patients (70%) had chronic migraine and 53 (42.7%) had medication‑overuse headache. The median number of prior prophylactics was 3 (Inter‑quartile range 2–5). At baseline, patients had 20.5 ± 8.5 headache days per month, decreasing 4.3 ± 8.4 days by 3 months (weeks 12–16) and by 4.7 ± 8.7 days by 6 months (paired Student’s t‑test, p < 0.001). The percentage of patients with a 50% response was 32.5% at 3 months and 31.7% at 6 months, while the retention rate was 85.0% and 58.3%. -

Combined Poziotinib with Manidipine Treatment Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Stem-Cell Proliferation and Stemness

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Combined Poziotinib with Manidipine Treatment Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Stem-Cell Proliferation and Stemness Heejin Lee 1,2, Jun Woo Kim 1,2, Dong-Seok Lee 2 and Sang-Hyun Min 1,* 1 New Drug Development Center, Daegu Gyeongbuk Medical Innovation Foundation (DGMIF), 80 Chumbok-ro, Dong-gu, Daegu 41061, Korea; [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (J.W.K.) 2 BK21 Plus KNU Creative BioResearch Group, School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 41566, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Fax: +82-53-790-5799 Received: 11 September 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 6 October 2020 Abstract: Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most lethal gynecological malignancy in women worldwide, with an overall 5 year survival rate below 30%. The low survival rate is associated with the persistence of cancer stem cells (CSCs) after chemotherapy. Therefore, CSC-targeting strategies are required for successful EOC treatment. Pan-human epidermal growth factor receptor 4 (HER4) and L-type calcium channels are highly expressed in ovarian CSCs, and treatment with the pan-HER inhibitor poziotinib or calcium channel blockers (CCBs) selectively inhibits the growth of ovarian CSCs via distinct molecular mechanisms. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that combination treatment with poziotinib and CCBs can synergistically inhibit the growth of ovarian CSCs. Combined treatment with poziotinib and manidipine (an L-type CCB) synergistically suppressed ovarian CSC sphere formation and viability compared with either drug alone. Moreover, combination treatment synergistically reduced the expression of stemness markers, including CD133, KLF4, and NANOG, and stemness-related signaling molecules, such as phospho-STAT5, phospho-AKT, phospho-ERK, and Wnt/β-catenin. -

Efficacy of Candesartan in the Treatment of Migraine in Hypertensive Patients

441 Case Report Efficacy of Candesartan in the Treatment of Migraine in Hypertensive Patients Kiyoshi OWADA*,** Triptans are usually administered for migraine, but cannot be given to patients with malfunctioning cardiac or cerebral vascular systems, which commonly accompany hypertension. This article focuses on 8 cases in which treatment with candesartan was successful in reducing both the incidence and severity of headache in hypertensive patients with migraine. The cases reported in this article showed a mean improvement in Mi- graine Disability Assessment score from 29.4 to 9 points and in blood pressure from 154.9/90.4 to 129.5/81.9 mmHg, suggesting that candesartan is an extremely attractive option for the treatment of mi- graine. Although recent studies have reported the efficacy of candesartan for treating migraine, there has been no description of its potential advantages over other prophylactic drugs. The present study included patients who could not tolerate triptans for whom triptans were contraindicated, several patients for whom other migraine prophylactic drugs showed little or no effect, and one patient for whom candesartan was pre- scribed initially for hypertension, but was also found to be therapeutic for migraines. Thus candesartan is considered to be a unique, attractive choice of prophylactic agent for migraine complicated by hyperten- sion. (Hypertens Res 2004; 27: 441–446) Key Words: angiotensin II receptor blocker, candesartan, migraine, hypertension ache intensity and duration when administered during the Introduction headache phase of the migraine (2, 3). However, these drugs are associated with specific adverse drug reactions (ADRs) Migraine affects approximately 10% of the adult population such as precordial distress and drowsiness, which cannot be and is particularly common in women. -

Study Protocol

CLINICAL STUDY PROTOCOL A Multicenter, Randomized, Open-label Trial Evaluating the Long-term Safety and Tolerability of Subcutaneous Administration of TEV-48125 for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine NCT Number: NCT03303105 PRT NO.: 406-102-00003 Version Date: 08 July 2019 (Version 5.0) Protocol 406-102-00003 <English Translation of Japanese Original> Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Investigational Medicinal Product TEV-48125 CLINICAL PROTOCOL A Multicenter, Randomized, Open-label Trial Evaluating the Long-term Safety and Tolerability of Subcutaneous Administration of TEV-48125 for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine Protocol No.: 406-102-00003 CONFIDENTIAL – PROPRIETARY INFORMATION Clinical Development Phase: 3 Sponsor: Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Immediately Reportable Event: PAREXEL International Global Medical Services, Pharmacovigilance E-mail address: [email protected] Issue Date (Original): 10 Aug 2017 Amendment 1: 30 Nov 2017 Amendment 2: 19 Jun 2018 Amendment 3: 28 Feb 2019 Amendment 4: 08 Jul 2019 Version No.: 5.0 (English translation, 06 Aug 2019) Protocol 406-102-00003 Protocol Synopsis Name of Sponsor: Otsuka Pharmaceutical Protocol No.: 406-102-00003 Co., Ltd. Name of Investigational Medicinal Product: TEV-48125 Protocol Title: A Multicenter, Randomized, Open-label Trial Evaluating the Long-term Safety and Tolerability of Subcutaneous Administration of TEV-48125 for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine Clinical Phase/ Phase 3 long-term safety trial Trial Type: Treatment Indication: Preventive treatment of chronic migraine (CM) and episodic migraine (EM) Objectives: To evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of subcutaneous administration of TEV-48125 (at 225 mg once monthly [except for a loading dose of 675 mg for CM patients] or at 675 mg every 3 months) for the preventive treatment of CM and EM patients Trial Design: A multicenter, randomized, open-label trial Subject Population: (1) 40 males or females with CM or EM, aged 18 to 70 years, inclusive. -

Medication-Overuse Headache CQ VI-1

VI Medication-overuse headache CQ VI-1 How is medication-overuse headache diagnosed? Recommendation Medication-overuse headache (MOH) is diagnosed according to the diagnostic criteria for “8.2 Medication-overuse headache” described in The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version), which was published in Cephalagia in 2013. Grade A Background and Objective The diagnostic criteria for medication-overuse headache described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-II)1) published in 2004 were revised in 20052) and 2006.3) This section discusses the changes as well as the issues concerning the diagnostic criteria for medication-overuse headache. Comments and Evidence In the International Classification of Headache Disorders 2nd Edition (ICHD-II) published in 2004,1) medication- overuse headache (MOH) is classified within the group of secondary headaches, under 8.Headache attributed to a substance or its withdrawal. MOH is characterized by: headache present on at least 15 days of a month, regular overuse of medications for over 3 months, headache developing or exacerbating markedly during medication overuse, and resolution of pain or returning to the previous pattern within 2 months after overuse is stopped. The subforms consist of headaches caused by individual medications: intake of ergotamine, triptan, opioid or combination analgesics on 10 or more days per month for over 3 months; or intake of simple analgesic on 15 or more days per month for over 3 months. The criteria