Nijinsky's Bloomsbury Ballet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Schooltime Performance Series Nutcracker

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the nutcracker National Ballet Theatre of Odessa about the meet the cultural A short history on ballet and promoting performance composer connections diversity in the dance form Prepare to be dazzled and enchanted by The Nutcracker, a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) was an important Russian timeless and beloved ballet performance that is perfect for children composer who is famous for his romantic, melodic and emotional Ballet’s roots In the 20th century, ballet continued to evolve with the emergence of of all ages and adults who have grown up watching it during the musical works that are still popular and performed to this day. He Ballet has its roots in Italian Renaissance court pageantry. During notable figures, such as Vaslav Nijinsky, a male ballet dancer virtuoso winter holiday season. is known for his masterful, enchanting compositions for classical weddings, female dancers would dress in lavish gowns that reached their who could dance en pointe, a rare skill among male dancers, and George Balanchine, a giant in ballet choreography in America. The Nutcracker, held all over the world, varies from one production ballet, such as The Nutcracker, Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty. ankles and dance before a crowd of aristocrats, wealthy merchants, and company to another with different names for the protagonists, Growing up, he was clearly musically gifted; Tchaikovsky politically-connected financiers, such as the Medici family of Florence. Today, ballet has morphed to include many different elements, besides traditional and classical. Contemporary ballet is based on choreography, and even new musical additions in some versions. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Claude Debussy in 2018: A Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies I. Debussy Perspectives, 1918-2018 RNCM, Manchester Monday, 19 March Paper session A: Debussy’s Style in History, Conference Room, 2.00-5.00 Chair: Marianne Wheeldon 2.00-2.30 – Mark DeVoto (Tufts University), ‘Debussy’s Evolving Style and Technique in Rodrigue et Chimène’ Claude Debussy’s Rodrigue et Chimène, on which he worked for two years in 1891-92 before abandoning it, is the most extensive of more than a dozen unfinished operatic projects that occupied him during his lifetime. It can also be regarded as a Franco-Wagnerian opera in the same tradition as Lalo’s Le Roi d’Ys (1888), Chabrier’s Gwendoline (1886), d’Indy’s Fervaal (1895), and Chausson’s Le Roi Arthus (1895), representing part of the absorption of the younger generation of French composers in Wagner’s operatic ideals, harmonic idiom, and quasi-medieval myth; yet this kinship, more than the weaknesses of Catulle Mendès’s libretto, may be the real reason that Debussy cast Rodrigue aside, recognising it as a necessary exercise to be discarded before he could find his own operatic voice (as he soon did in Pelléas et Mélisande, beginning in 1893). The sketches for Rodrigue et Chimène shed considerable light on the evolution of Debussy’s technique in dramatic construction as well as his idiosyncratic approach to tonal form. Even in its unfinished state — comprising three out of a projected four acts — the opera represents an impressive transitional stage between the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1890) and the full emergence of his genius, beginning with the String Quartet (1893) and the Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (1894). -

The Exemplary Daughterhood of Irina Nijinska

ven before her birth in 1913, Irina Nijinska w.as Choreographer making history. Her uncle, Vaslav Nijinsky, Bronislava Nijinska in Revival: E was choreographing Le Sacre du Printemps, with her mother, Bronislava Nijinska, as the Chosen Maiden. But Irina was on the way, and Bronislava had The Exemplary to withdraw. If Sacre lost a great performance, Bronis lava gained an heir. Thanks to Irina, Nijinska's long neglected career has finally received the critical and Daughterhood public recognition it deserves. From the start Irina was that ballet anomaly-a of Irina Nijinska chosen daughter. Under her mother's tutelage, she did her first plies. At six, she stayed up late for lectures at the Ecole de Mouv.ement, Nijinska's revolutionary stu by Lynn Garafola dio in Kiev. In Paris, where the family settled in the 1920s, Irina studied with her mother's student Eugene Lipitzki, graduating at fifteen to her mother's own cla~s The DTH revival of , for the Ida Rubinstein company, where she also sat in Rondo Capriccioso, Nijinska's on rehearsals. Irina made her professional debut in London in last ballet, is ·her daugther 1930. The company was headed by Olga Spessivtzeva, Irina's latest project. and Irina danced under the name Istomina, the bal lerina beloved by Pushkin. That year, too, she toured with the Opera Russe a Paris, one of many ensembles · associated with her mother in which she performed. These included the Rubinstein company, as well as Theatre de la Danse Nijinska, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and the Polish Ballet. -

Ballets Russes Press

A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE THEY CAME. THEY DANCED. OUR WORLD WAS NEVER THE SAME. BALLETS RUSSES a film by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller Unearthing a treasure trove of archival footage, filmmakers Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine have fashioned a dazzlingly entrancing ode to the rev- olutionary twentieth-century dance troupe known as the Ballets Russes. What began as a group of Russian refugees who never danced in Russia became not one but two rival dance troupes who fought the infamous “ballet battles” that consumed London society before World War II. BALLETS RUSSES maps the company’s Diaghilev-era beginnings in turn- of-the-century Paris—when artists such as Nijinsky, Balanchine, Picasso, Miró, Matisse, and Stravinsky united in an unparalleled collaboration—to its halcyon days of the 1930s and ’40s, when the Ballets Russes toured America, astonishing audiences schooled in vaudeville with artistry never before seen, to its demise in the 1950s and ’60s when rising costs, rock- eting egos, outside competition, and internal mismanagement ultimately brought this revered company to its knees. Directed with consummate invention and infused with juicy anecdotal interviews from many of the company’s glamorous stars, BALLETS RUSSES treats modern audiences to a rare glimpse of the singularly remarkable merger of Russian, American, European, and Latin American dancers, choreographers, composers, and designers that transformed the face of ballet for generations to come. — Sundance Film Festival 2005 FILMMAKERS’ STATEMENT AND PRODUCTION NOTES In January 2000, our Co-Producers, Robert Hawk and Douglas Blair Turnbaugh, came to us with the idea of filming what they described as a once-in-a-lifetime event. -

The Institute of Modern Russian Culture

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 61, February, 2011 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089‐4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740‐2735 or (213) 743‐2531 Fax: (213) 740‐8550; E: [email protected] website: hƩp://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the sixty-first biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue which appeared in August, 2010. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the fall and winter of 2010. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2010 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 for overseas airmail). RUSSIA If some observers are perturbed by the ostensible westernization of contemporary Russia and the threat to the distinctiveness of her nationhood, they should look beyond the fitnes-klub and the shopping-tsentr – to the persistent absurdities and paradoxes still deeply characteristic of Russian culture. In Moscow, for example, paradoxes and enigmas abound – to the bewilderment of the Western tourist and to the gratification of the Russianist, all of whom may ask why – 1. the Leningradskoe Highway goes to St. Petersburg; 2. the metro stop for the Russian State Library is still called Lenin Library Station; 3. there are two different stations called “Arbatskaia” on two different metro lines and two different stations called “Smolenskaia” on two different metro lines; 4. -

A'level Dance Knowledge Organiser Christopher

A’LEVEL DANCE KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER CHRISTOPHER BRUCE Training and background Influences • Christopher Bruce's interest in varied forms of • Walter Gore: Bruce briefly performed with Walter Gore’s company, London Ballet, in 1963, whilst a student at the Ballet choreography developed early in his career from his own Rambert School in London. Gore was a pupil of Massine and Marie Rambert in the 1930s before becoming one of Ballet exposure to classical, contemporary and popular dance. Rambert’s earliest significant classical choreographers. His influence on Bruce is seen less in classical technique and more in the • Bruce's father who introduced him to dance, believing it abstract presentation of social and psychological realism. This can of course be a characteristic of Rambert Ballet’s ‘house could provide a useful career and would help strengthen style’, post-1966. his legs, damaged by polio. • His early training, at the Benson Stage Academy, • Norman Morrice: As Associate Artistic Director of Ballet Rambert in 1966, Morrice was interested in exploring contemporary Scarborough, included ballet, tap and acrobatic dancing - themes and social comment. He was responsible for the company’s change in direction to a modern dance company as he all elements which have emerged in his choreography. introduced Graham technique to be taught alongside ballet. • At the age of thirteen he attended the Ballet Rambert School and Rambert has provided the most consistent • Glen Tetley: Glen Tetley drew on balletic and Graham vocabulary in his pieces, teaching Bruce that ‘the motive for the umbrella for his work since. movement comes from the centre of the body … from this base we use classical ballet as an extension to give wider range and • After a brief spell with Walter Gore's London Ballet, he variety of movement’. -

We Warred Over Art: Pandemonium at Le Sacre Du Printemps

We Warred Over Art: Pandemonium at Le Sacre du Printemps Elizabeth Blair Davis Honors Art History Thesis April 3, 2015 Table of Contents I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………1-9 II. Chapter I: The World of Russian Art...………………………………………………10-20 III. Chapter II: The Russian Orient….……………………………………………………21-33 IV. Chapter III: Russia’s ‘Primitive’ Roots.....……………………………………….…..34-48 V. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………49-51 VI. Bibliography………………………………………………………………………….52-55 VII. Images…………………………………………………………………………...……56-86 1 Introduction Standing in her box, her tiara askew, the old comtesse de Pourtalès brandished her fan and cried red-faced: ‘This is the first time in sixty years that anyone has dared make fun of me!’ The worthy lady was sincere; she thought it was a hoax. — Jean Cocteau1 On the evening of May 29, 1913, in the Théatre des Champs Elysées in Paris, the Ballets Russes’ premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps, inspired magnificent scandal. The ballet, translated into English as The Rite of Spring, depicted a Russian pagan ritual of human sacrifice. It completely departed from the expectations of twentieth-century French viewers, leading quite literally to a riot in the theater.2 Scholars including Thomas Kelly, Theodore Ziolkowski, Lynn Garafola, and Alexander Schouvaloff have discussed the premiere of The Rite of Spring extensively in terms of music and dance history, and yet, despite its commonalities with modern art of the period, it has not been discussed in terms of an art historical context. As the primary liaison between French and Russian artistic spheres, Sergei Diaghilev possessed the responsibility of presenting Russian culture in a manner that appealed to French audiences. -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Barbara Barry, Musicologist-Head of Music History

PROGRAM NOTES by Barbara Barry, musicologist-head of music history Claude Debussy (1862 -1918) Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun It may seem strange at first to think of Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun as a revolutionary work. Revolutions are usually thought of as loud and explosive, breaking free from whatever the chains are – political, ideological or emotional repression. But there are other kinds of revolution, quieter, more subtle, that equally change the way we view and understand the world. L’après midi d’un faune (1894) is a case study in this kind of soft revolution. A recreation rather than influenced by Mallarmé’s poem of 1876 about a faun on a warm summer afternoon, with all the mythological associations with Pan and Syrinx, and more recently the tales of Narnia. The faun gradually emerges from sleep. Sensuously stretching his limbs, he views the world through eyes now half-opened, now half-closed. Debussy wrote about his poetic, dream-like piece: “The music of this prelude is a very free illustration of Mallarmé’s beautiful poem. By no means does it claim to be a synthesis of it. Rather there is a succession of scenes through which pass the desires and dreams of the faun in the heat of the afternoon. Then, tired of pursuing the timorous flight of nymphs and naiads, he succumbs to intoxicating sleep, in which he can finally realize his dreams of possession in universal Nature.” Debussy’s music recreates Mallarmé’s sensuous half-world between dreaming and waking at the intersection of the human and the mythological. -

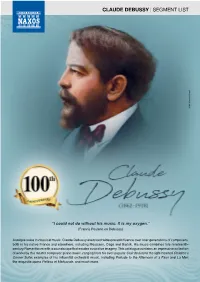

CLAUDE DEBUSSY | SEGMENT LIST © HNH International

CLAUDE DEBUSSY | SEGMENT LIST © HNH International “I could not do without his music. It is my oxygen.” (Francis Poulenc on Debussy) A unique voice in classical music, Claude Debussy exercised widespread influence over later generations of composers, both in his native France and elsewhere, including Messiaen, Cage and Bartók. His music combines late nineteenth- century Romanticism with a soundscape that exudes evocative imagery. This catalogue contains an impressive collection of works by this master composer: piano music, ranging from his ever-popular Clair de lune to the light-hearted Children’s Corner Suite; examples of his influential orchestral music, including Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun and La Mer; the exquisite opera Pelléas et Mélisande, and much more. © 2018 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 1 of 2 LABEL CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS UPC A Musical Journey DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 2.110544 FRANCE: A Musical Tour of Provence Various Artists 747313554454 (1862–1918) Music by Debussy and Ravel [DVD] DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.556663 BEST OF DEBUSSY Various Artists 0730099666329 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Cello Recital – Cello Sonata Tatjana Vassiljeva, Cello / Naxos 8.555762 0747313576227 (1862–1918) (+STRAVINSKY / BRITTEN / DUTILLEUX) Yumiko Arabe, Piano DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.556788 Chill With Debussy Various Artists 0730099678827 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Clair de lune and Other Piano Favorites • Naxos 8.555800 Francois-Joël Thiollier, Piano 0747313580026 (1862–1918) Arabesques • Reflets dans l'eau DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.509002 Complete Orchestral Works [9CDs Boxed Set] Various Artists 747313900237 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Early Works for Piano Duet – Naxos 8.572385 Ivo Haah, Adrienne Soos, Piano 747313238576 (1862–1918) Printemps • Le triomphe de Bacchus • Symphony in B Minor DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.578077-78 Easy-Listening Piano Classics (+RAVEL) [2CDs] Various Artists 747313807772 (1862–1918) DEBUSSY, Claude Naxos 8.572472 En blanc et noir (+MESSIAEN) Håkon Austbø, Ralph van Raat, Piano 747313247271 (1862–1918) Four-Hand Piano Music, Vol. -

Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony Release All-Debussy Album on Sfs Media October 28, 2016

Press Contacts: Public Relations National Press Representation: San Francisco Symphony Shuman Associates (415) 503-5474 (212) 315-1300 [email protected] [email protected] www.sfsymphony.org/press FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE / SEPTEMBER 27, 2016 (High resolution images available for download from the SFS Media’s Online Press Kit) MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS AND THE SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY RELEASE ALL-DEBUSSY ALBUM ON SFS MEDIA OCTOBER 28, 2016 Album Includes Images pour orchestre, Jeux, and La plus que lente Pre-order September 27 on iTunes.com/SFSymphony and SFSymphony.org/Debussy SAN FRANCISCO, September 27, 2016 – Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT) and the San Francisco Symphony (SFS) will release an all-Debussy album featuring three works that illustrate the French composer’s mastery with orchestration including Images pour orchestre, Jeux, and La plus que lente, on the Orchestra’s Grammy Award- winning SFS Media label on Friday, October 28, 2016. The recording will be available for pre-order on iTunes.com/SFSymphony and SFSymphony.org/Debussy on Tuesday, September 27, 2016. This recording is presented by SFS Media in premium audio hybrid SACD as well as studio master-quality download. Michael Tilson Thomas comments, “Right from the start of my musical life, Debussy’s music captivated me. He had a genius for sensing the essential quality of a particular instrument’s voice and creating for it evocative solos that have become emblematic. His sense of unusual blends of different instruments was also original and highly