Mass Fires and Fire Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Module 4: Fire Management

Module 4: Fire Management Photo: Michal Bukowski Statue of St. Florian, the patron saint of firefighters, erected in the XIX century after a great fire in the village of Lipnica Murowana, in Lesser Poland. Module 4: Fire Management Proposed Agenda Time Section name 8:00 8:30 Welcome 8:30 9:00 Introduction and Objectives 9:00 9:30 Activity I and discussion 9:30 10:00 Break 10:00 10:30 History and Policies 10:30 11:00 Standards and Orders 11:00 11:30 1910 revisited 11:30 12:00 How Things Change 12:00 12:30 Lunch 12:30 1:30 Incident Command System 1:30 2:00 Wildland Fires 2:00 2:30 Structural Fires 2:30 3:30 Risk and Safety 3:30 4:00 Lessons Learned 4:00 4:30 Egos, Personalities, and Politics 4:30 5:00 Wrap-up 5:00 5:30 Discuss plans for the fire field trip 2 Module 4: Fire Management Overview Content Outline This module focuses on the history and social ■ Introduction contexts of fire management, how those contexts ■ History and Policies influence policies, how fire management evolved ❏ The Incident Command System over time, and basic fire management objectives. ❏ The NWCG ❏ More tragedies mean more adaptation Learning Objectives ❏ Standardization ■ Wildland and Structural Fires ■ Understand the history of wildland fire ❏ Wildland fires fighting in a cultural, political, and social ❏ Structure fires context ❏ Risk ■ Identify and define different approaches to ■ Put it out suppressing and controlling fire ❏ Fire prevention ■ Understand the management objectives for ❏ Fire control fire suppression (wildland and structure) ❏ Fire exclusion ■ Compare and contrast the uses of fire con- ❏ Fire suppression trol vs. -

Preparation for Initial Company Operations-Student Manual

Preparation for Initial Company Operations PICO-Student Manual 1st Edition, 5th Printing-April 2014 FEMA/USFA/NFA PICO-SM April 2014 Preparation for Initial Company Operations 1st Edition, 5th Printing Preparation for Initial Company Operations PICO-Student Manual 1st Edition, 5th Printing-April 2014 This Student Manual may contain material that is copyright protected. USFA has been granted a license to use that material only for NFA-sponsored course deliveries as part of the course materials, and it shall not be duplicated without consent of the copyright holder. States wishing to use these materials as part of state-sponsorship and/or third parties wishing to use these materials must obtain permission to use the copyright material(s) from the copyright holder prior to teaching the course. PREPARATION FOR INITIAL COMPANY OPERATIONS NOTICE: This material has been developed by the National Fire Academy (NFA) of the United States Fire Administration (USFA) for use by State and metropolitan fire training programs. NFA endorsement of this material is conditional on use without modification. NFA material, whether printed text or software, may not be used in any manner that would mislead or that would suggest or imply endorsement by NFA of any commercial product, process, or service. ii PREPARATION FOR INITIAL COMPANY OPERATIONS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY UNITED STATES FIRE ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL FIRE ACADEMY FOREWORD The U.S. Fire Administration (USFA), an important component of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), serves the leadership of this Nation as the DHS's fire protection and emergency response expert. The USFA is located at the National Emergency Training Center (NETC) in Emmitsburg, Maryland, and includes the National Fire Academy (NFA), National Fire Data Center (NFDC), and the National Fire Programs (NFP). -

Sunrise Fire Rescue Operations and Policy Manual

UPDATED ON 6/21/2016 OPERATIONS AND POLICIES MANUAL Sunrise Fire Rescue Operations & Policies Manual Index June 21, 2016 SECTION 1 ORGANIZATION 100.00 Mission Statement August 4, 2003 100.01 Organizational Structure October 1, 2013 100.02 Operations & Policies Manual (OPM) February 3, 2014 SECTION 2 HUMAN RESOURCES 200.00 Duties & Responsibilities 200.01 Firefighter/EMT December 23, 2014 200.02 Firefighter/Paramedic December 23, 2014 200.03 Fire Inspector December 23, 2014 200.04 Driver Operator December 23, 2014 200.05 Rescue Lieutenant – Section 1 Shift December 23, 2014 200.05 Rescue Lieutenant – Section 2 Non Shift December 23, 2014 200.06 Fire Captain December 23, 2014 Sect. 1 Fire Captain EMS Shift Supervisor December 23, 2014 Sect. 2 Fire Captain EMS Non Shift December 23, 2014 Sect. 3 Fire Captain Fire Life Safety December 23, 2014 Sect. 4 Fire Captain Plan Review December 23, 2014 Sect. 5 Fire Captain Logistics December 23, 2014 Sect. 6 Fire Captain Special Operations July 28, 2010 Sect. 7 Fire captain Training April 30, 2013 200.07 Fire Marshal April 27, 2011 200.08 Battalion Chief April 30, 2013 Sect. 1 Support Battalion Chief April 30, 2013 Sect 2 Emergency Management Battalion Chief April 30, 2013 200.09 Fire Division Chief April 30, 2013 201.00 Promotional Qualifications 201.01 Entry Level/Firefighter December 23, 2014 201.02 Driver Operator December 23, 2014 201.03 Rescue Lieutenant December 23, 2014 201.04 Fire Captain December 23, 2014 201.06 Battalion Chief December 23, 2014 201.07 Special Operations Team Member April -

Francis Marion Plan FEIS Chapters 1 to 4

In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. -

Countrytime - Best of 320 Titel, 20,1 Std., 1,88 GB

Seite 1 von 13 -CountryTime - Best Of 320 Titel, 20,1 Std., 1,88 GB Name Dauer Album Künstler 1 Absence of the heart 3:31 Everything's Gonna Be Alright - Deana Carter - 1998 (RS) Carter Deana 2 Ain't i the lucky one 2:14 The Essential Marty Robbins: Robbins Marty 3 All i have to do is dream 2:33 Duets - 36 of the Worlds Greatest Ever Duets - Comp 1997 (CD… Gentry Bobbie & Campbell Glen 4 All of that love from here 3:25 Wynonna - Wynonna Judd - 1992 (RS) Judd Wynonna 5 All the things we've never done 3:25 Wild Angels - Martina McBride - 1995 (RS) McBride Martina 6 Already gone 4:36 Love On The Inside - Sugarland - 2008 (RS) Sugarland 7 Already somebody's lover 3:36 Lila - Lila McCann - 1997 (VA) McCann Lila 8 Always on your side 4:15 Wildflower - Sheryl Crow - 2005 (RS-VBR) Crow Sheryl 9 Always on your side (ft Sting) 4:11 Hits And Rarities - Sheryl Crow - Comp 2007 CD1 (RS-VBR) Crow Sheryl 10 Amoureuse 3:39 Music Makes My Day - Olivia Newton-John - 1973 (RS) Newton-John Olivia 11 Angels in waiting 3:37 Tammy Cochran - Tammy Cochran - 2001 (VA) Cochran Tammy 12 Any woman 3:21 Just The Same - Terri Clark - 1996 (RS) Clark Terri 13 Anyone who had a heart 4:02 Sing: Chapter 1 - Wynonna Judd - 2009 (RS) Judd Wynonna 14 Anyone who had a heart 3:17 Indigo - Women Of Song - Olivia Newton-John - 2004 (RS) Newton-John Olivia 15 Anyway 4:41 Waking Up Laughing - Martina McBride - 2007 (RS) McBride Martina 16 At the end of the day 3:36 Lisa Brokop- Lisa Brokop - 1995 (IS) Brokop Lisa 17 Attention 3:35 Back With A Heart - Olivia Newton-John - 1998 -

An Early History of Southern Barbecue

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 Smokin' Out the Truth: An Early History of Southern Barbecue Morgan Vivianne Di Santo Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the American Material Culture Commons, and the United States History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Di Santo, Morgan Vivianne, "Smokin' Out the Truth: An Early History of Southern Barbecue" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 131. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/131 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Smokin’ Out the Truth: An Early History of Southern Barbecue Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Morgan Di Santo Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2016 In loving memory of James Gregan. Acknowledgements I would first like to express my deep gratitude to my advisor, Christian Crouch. I am forever grateful for her patience, compassion, and wisdom. She believed in me and reminded me to have confidence in my own abilities. -

Tanya Tucker

Tanya Tucker │Biography │ One of country music’s greatest legends, Tanya Tucker, has just released her much anticipated new CD, My Turn, on Saguaro Road Records. On this new album Tucker takes classic country songs originally recorded by the all time great male legends of the time and turns the tables, giving classics such as “You Don’t Know Me” and “Oh, Lonesome Me” a powerful reconstruction from a woman’s point of view. Only 13 when her provocative “Delta Dawn” caused a nationwide stir and became a Top 10 country hit, Tucker has built one of the most successful and compelling careers in music. Considered one of the very few females of the “outlaw” country movement, she holds a Grammy award, two Country Music Association awards, Two Academy of Country Music awards, and three CMT Awards. 23 of her albums have landed in the country Top 40 chart since her 1972 debut, and she has amassed 10 #1 country singles, 33 that have reached the Top 5, and 41 in the Top 10. Always reinventing herself, Tanya again became a media darling in 2005 as the star of her own television reality series, Tuckerville. The primetime series was a huge hit for TLC, generating the cable network’s highest Neilsen ratings ever, and guaranteed the show’s return in 2006. Having sold over 50 million records over the last three decades, country music icon Tanya Tucker is among the all-time best selling female vocalists in country music. “Surprisingly mature at a very young age, Tanya Tucker continues to grow today, taming and conquering tunes long assumed to be a man’s territory. -

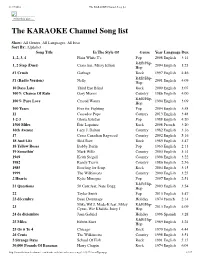

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Social and Economic Issues of the Hayman Fire

Social and Economic Issues of the Hayman Fire Brian Kent, Krista Gebert, Sarah McCaffrey, Wade Martin, David Calkin, Ervin Schuster, Ingrid Martin, Holly Wise Bender, Greg Alward, Yoshitaka Kumagai, Patricia J. Cohn, Matt Carroll, Dan Williams, Carol Ekarius Introduction ____________________ frequency and magnitude of wildfires has increased, especially in lower elevation Ponderosa pine and mixed On June 26, 2002, U.S. Representative Mark Udall conifer forests because of significant fuel buildups and wrote the US Forest Service Chief, requesting that the extreme drought, more wildfires are causing signifi- Forest Service conduct an analysis of the Hayman cant damage and disruption to both social and eco- Fire. In response to the Congressman’s letter, five nomic systems. This trend ensures that the interplay teams were established in August, 2002 to analyze between wildland fire management and human di- various aspects of the Hayman Fire experience. This mensions issues takes on far greater importance than report describes the Hayman Fire analysis work con- it did historically. As pointed out in (Machlis and ducted by the social/economic team and presents our others 2002): findings. The human dimension of Federal wildland fire man- When a fire the size and intensity of the Hayman agement – the relationship of people and wildland fire in Fire occurs largely in an urban/wildland area as highly America – is an important and driving force in how Federal agencies respond to wildland fire, now and in the developed as the Colorado Front Range, the social and future. In many ways, it is the critical element, for the economic effects or consequences will be extensive, management of wildland fire is very much the manage- complex, and long lasting. -

A Preliminary Inventory of the Willie Nelson Recording Collection 1954

A Preliminary Inventory of the Willie Nelson Recording Collection 1954-2010 Collection 066 Descriptive Summary Creator: Artificial Collection Title: The Willie Nelson Recording Collection Dates: 1954-2010 Abstract: The Willie Nelson Recording Collection spans 1954-2010, chronicling the career of renowned Texas singer, songwriter, and bandleader. The collection contains 877 recordings, including LPs, 45 rpms, audio cassettes, compact discs, VHS cassettes, and DVDs. Identification: Collection 066 Extent: 33 boxes (13 linear feet) Language: English. Repository: Southwestern Writers Collection, The Wittliff Collections, Alkek Library, Texas State University-San Marcos Scope and Contents Note The Willie Nelson Recording Collection spans 1954-2010, chronicling the career of renowned Texas singer, songwriter, and bandleader. The collection contains 877 recordings, including LPs, 45 rpms, audio cassettes, compact discs, VHS cassettes, and DVDs. Included in the collection are recordings under Nelson’s leadership as well as recordings on which he is a guest musician, producer, or songwriter. Highlights from the collection include Nelson’s first 45 rpm record released under his name, “No Place For Me” b/w “Lumberjack” (pictured above), numerous live recordings, studio demos, and deluxe-edition CDs with rare and previously unreleased material. Some of Nelson’s earliest recordings as a guest musician and songwriter are featured in the collection that represents the bulk of Nelson’s official discography. The collection is arranged chronologically by publication date. Not every recording is dated, and some are listed with an approximate date of release. Some recordings are listed by their original release date, not the date of production of that particular disc, cassette, etc. For example, The Troublemaker was originally released on LP in 1976. -

Fire Management Plan

National park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area Oneida, Tennessee Fire Management Plan For Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area September 2004 U.S. Department of the Interior National park Service Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area Kentucky and Tennessee EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA 1.0 INTRODUCTION The management policies (Directors Order – 18, November 1998 and Reference Manual – RM – 18, February 1999) for the National Park Service (NPS) require that all Park Service areas with vegetation capable of supporting fire develop a Fire Management Plan1. The use of fire to achieve resource management objectives is addressed in the National Area’s Resource Management Plan (1996). This plan implements the selected management actions from the Resource Management Plan, with over-all guidance provided by the General Management Plan (2000). The purpose of this plan is to outline in as detailed a manner as possible, actions that will be taken by Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area (National Area) in meeting the fire management goals established for the area. Authority for carrying out a fire management program at the National Area originates with the Organic Act of the National Park System, August 25, 1916. The Organic Act states the primary goal of the National Park Service is to preserve and protect the natural and cultural resources found on lands under its management in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future generations. The Organic Act -

Rhythm & Blues...47

COUNTRY .......................2 POP.............................79 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............14 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................87 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......15 LATIN ............................91 WESTERN..........................17 JAZZ .............................91 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................18 SOUNDTRACKS .....................92 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........18 SWING ...........................93 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....19 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE.......19 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............94 BLUEGRASS ........................22 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............99 INSTRUMENTAL .....................24 OLDTIME ..........................25 BOOKS/BÜCHER ................101 HAWAII ...........................26 DISCOGRAPHIES ....................109 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................26 CHARTS ..........................110 FOLK .............................27 SINGLES ..........................110 CD SINGLES .......................106 ROCK & ROLL ...................30 POSTER ...........................106 LABEL R&R .........................40 R&R SOUNDTRACKS .................41 DVD ............................109 R&R SPECIAL COLLECTIONS............41 VINYL...........................120 ELVIS .............................42 RHYTHM & BLUES...............47 ARTIST INDEX...................122 BLUES ............................51 ORDER TERMS/VERSANDBEDINGUNGEN..127 GOSPEL ...........................52 SOUL.............................53 PRICELIST/PREISLISTE ...........128 VOCAL GROUPS ....................55 LABEL