Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Freston, Viacom Inc. Co-President, Co-Chief Operating

Tom Freston, Viacom Inc. Co-President, Co-Chief Operating Officer Presentation Transcript Merrill Lynch Media and Entertainment Conference Event Date/Time: September 13, 2005, 4:45pm E.D.S.T. Filed by: Viacom Inc. Pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended Commission File No.: 001-09533 Subject Company: Viacom Inc. - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Jessica Reif Cohen - Analyst - Merrill Lynch All right, we will get started with the afternoon. With the split up of Viacom expected no later than the first quarter of 2006, Tom Freston's role will change again. Having led the most successful cable network for the past 25-plus years, although he doesn't look it, Tom Freston's challenge is to extend this brand success with consumers across multiple platforms, both wired and wireless, while satisfying investors' demand for growth across multiple metrics. We certainly believe that management is up to this task. Please welcome Tom Freston, Co-President and Co-COO of Viacom. But before Tom takes the stage, we have a video to show you. (shows video, playing "Desire" by U2) - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Tom Freston - Viacom - Co-President, Co-COO Well, that ought to wake you a little bit after lunch. Good afternoon, everybody. I'm Tom Freston. Thank you, Jessica. It's nice to be here in Pasadena. This time last year, Leslie Moonves and I were settling into our new positions in a Company that was a really wide conglomeration of media assets with varying growth rates and prospects. You can see them all up there now. And by now, most of you are familiar with the rationale behind the split of Viacom, which we expect to happen at the end of this year or the beginning of next year. -

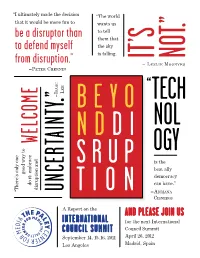

Be a Disruptor Than to Defend Myself from Disruption.”

“I ultimately made the decision “The world that it would be more fun to wants us be a disruptor than to tell them that to defend myself the sky is falling. from disruption.” IT’s NOT.” – Le s L i e Mo o n v e s –Pe t e r Ch e r n i n aac e e s i ” – L “ . BEYO TECH NOL WELCOME NDDI OGY SRUP is the best ally democracy can have.” disruption and UNCERTAINTY good way to do it: embrace “There’s only one TION –Ad r i A n A Ci s n e r o s A Report on the AND PLEASE JOIN US INTERNATIONAL for the next International COUNCIL SUMMIT Council Summit September 14, 15, 16, 2011 April 26, 2012 Los Angeles Madrid, Spain CONTENTS A STEP BEYOND DISRUPTION 3 | A STEP BEYOND DISRUPTION he 2011 gathering of The Paley Center for Me- Tumblr feeds, and other helpful info. In addi- dia’s International Council marked the first time tion, we livestreamed the event on our Web site, 4 | A FORMULA FOR SUCCESS: EMBRacE DISRUPTION in its sixteen-year history that we convened in reaching viewers in over 140 countries. Los Angeles, at our beautiful home in Beverly To view archived streams of the sessions, visit 8 | SNAPSHOTS FROM THE COCKTAIL PaRTY AT THE PaLEY CENTER Hills. There, we assembled a group of the most the IC 2011 video gallery on our Web site at http:// influential thinkers in the global media and en- www.paleycenter.org/ic-2011-la-livestream. -

Filing Under Rule 425 Under the Securities Act of 1933, As Amended Subject Company: Viacom Inc

Filing under Rule 425 under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended Subject Company: Viacom Inc. Subject Company's Commission File No.: 001-09553 TO: All Viacom Employees FROM: Sumner Redstone DATE: June 14, 2005 We have some very exciting and important news to share with you. Today, the Viacom Board of Directors approved the creation of two separate publicly traded companies from Viacom's businesses through a spin-off to Viacom shareholders. Even for a company with a history of industry-leading milestones and significant successes, this is a landmark announcement. This decision was the result of careful and thorough deliberation by the Viacom Board of Directors, who, working with me and with the Viacom management team, considered a number of strategic options that we felt could maximize the future growth of our businesses and unlock the value of our assets. Viacom's businesses are vibrant and we believe that the creation of two separate companies will not only enhance our strength, but also improve our strategic, operational and financial flexibility. In many ways, today's decision is a natural extension of the path we laid out in creating Viacom. We are retaining the significant advantages we captured in the Paramount and CBS mergers and, at the same time, recognizing the need to adapt to a changing competitive environment. We are proud of what we have created here at Viacom, and want to ensure we can efficiently capitalize on our skills and our innovative ideas, as well as all the business opportunities that arise -- while recognizing the significant untapped business and investment potential of our brands. -

Schapiro Exhibit

Schapiro Exhibit 195 Subject: Re: Vanity Fair/Sumner Redstone From: Robinson, Carole -:EX:/O=VIACOM/OU=MTVUSA/CN=RECIPIENTS/CN= ROBINSOC;: To: Freston, Tom Cc: Date: Wed, 01 Nov 2006 02:46:10 +0000 -----Original Message----- From: Freston, Tom To: Robinson, Carole Sent: Tue Oct 31 21:29:322006 Subject: Re: Vanity Fair/Sumner Redstone -----Original Message----- From: Robinson, Carole To: Freston, Tom Sent: Tue Oct 3121:16:032006 Subject: Re: Vanity Fair/Sumner Redstone -----Original Message----- From: Freston, Tom To: Robinson, Carole Sent: Tue Oct 31 18:58:592006 Subject: Re: Vanity Fair/Sumner Redstone -----Original Message----- Highly Confidential VIA09076933 From: Robinson, Carole To: Freston, Tom Sent: Tue Oct 3111:25:52 2006 Subject: Vanity Fair/Sumner Redstone The New Establishment Sumner Redstone and one of the saltwater fishtanks in his home in Beverly Park, California, on October 6. Photograph by Don Flood. Sleeping with the Fishes Happy at last, Sumner Redstone is still far from mellow-witness his public trashing of superstar Tom Cruise and firing of Viacom C.EO, Tom Freston. At home in Beverly Hills, the 83-year-old tycoon and his new wife, Paula, reveal their love story, her role in the Cruise decision, and what he claims was Freston's big mistake. by Bryan Burrough December 2006 High on the slopes above Beverly Hills, so high the clouds sometimes waft beneath it, one of the most exclusive enclaves in Southern California hides behind a pair of mammoth iron gates. If you're expected, a security guard will push a button and the gates will slowly open. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 June 1, 2004 --------------------------------------------------- Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) VIACOM INC. --------------------------------------------------- (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-09553 04-2949533 - ------------------------------ ------------------------ --------------------------------------- State or other jurisdiction of (Commission File Number) (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number) incorporation) 1515 Broadway, New York, NY 10036 --------------------------------------------------- (Address of principal executive offices) (zip code) (212) 258-6000 --------------------------------------------------- (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Item 5. Other Events. On June 1, 2004, the Board of Directors of Viacom Inc. ("Viacom") announced that Tom Freston and Leslie Moonves have been appointed Co-Presidents and Co-Chief Operating Officers of Viacom. Mr. Freston and Mr. Moonves succeed Mel Karmazin, who has resigned. In addition, the Viacom Board of Directors announced a corporate succession plan. Attached hereto as Exhibit 99.1 is a press release issued by Viacom on June 1, 2004, which is incorporated herein by reference. Also attached hereto (1) as Exhibit 3.1 are Amended and Restated By-laws of Viacom Inc., adopted on June 1, 2004 and (2) as Exhibit 10.1 is an Agreement, dated as of June 1, 2004, by and between Viacom and Mr. Karmazin. Item 7. Financial Statements and Exhibits. (c) Exhibits. Exhibit Number Description of Exhibit 3.1 Amended and Restated By-laws of Viacom Inc., adopted June 1, 2004 10.1 Agreement, dated as of June 1, 2004, by and between Viacom Inc. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549-1004 ______________________________________ FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): APRIL 22, 2003 VIACOM INC. ________________________________________ (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 1-9553 04-2949533 --------------- ------------ -------------- (State or other Commission (IRS Employer jurisdiction File Number Identification of incorporation) Number) 1515 Broadway, New York, NY 10036 ----------------------------------------------------- (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (212) 258-6000 ------------------------------------- (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Item 5. Other Events ------------ On April 22, 2003, Viacom Inc. ("Viacom" or the "Registrant") announced that it had agreed to acquire from AOL Time Warner Inc. ("AOL") the remaining 50% partnership interest of Comedy Partners, a New York general partnership ("Comedy Partners"), that it does not already own for $1.225 billion in cash. Comedy Partners, which operates the cable channel Comedy Central, is currently a joint venture between wholly-owned subsidiaries of Viacom and AOL. The acquisition is expected to close in the second quarter of 2003, and is subject to the expiration of antitrust waiting periods. A copy of the press release issued by Viacom dated April 22, 2003 relating to the above-described transaction is attached hereto as Exhibit 99. Item 7. Financial Statements and Exhibits --------------------------------- (c) Exhibits Exhibit No. 99 Press release issued by the Registrant dated April 22, 2003. SIGNATURE Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the Registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned hereunto duly authorized. -

United Technologies / Viacom Letter Re

233503 April 21,2005 via Federal Express Mr. Brad W. Bradley EPA Project Coordinator U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region V, Mailcode SR-6J 77 W. Jackson Boulevard Chicago, IL 60604 W Re: In the Matter of Little Mississinewa Site CERCLA Docket No. V-W-'05-C-812 Dear Mr. Bradley: I. Introduction On or about April 4, 2005, the United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region V ("EPA"), issued an Administrative Order for Remedial Action (Docket No. V-W-'05-C-812) (the "Order" or "Unilateral Order") to Viacom Inc. ("Viacom") and United Technologies Corporation on behalf of Lear Corporation Automotive Systems ("UTC") (collectively, "Respondents"), directing those parties to implement the approved remedial design for the Little Mississinewa Site in Union , City, Indiana (the "Site"). The purposes of this letter are: (1) to advise EPA, pursuant to Section XXIV of the Order, of Respondents' intention to comply with the terms of the Order to the extent such compliance is required under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act ("CERCLA"), 42 U.S.C. §§9601, et seq., and its implementing regulations, namely the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan ("NCP"), 40 C.F.R. Part 300; and (2) to outline several objections and defenses that Respondents have to the Order, as issued. II. General Objections and Reservation of Rights As an initial matter, it should be noted that by setting forth any objections or defenses in this letter, or by submitting this letter at all, Respondents do not waive, and hereby specifically reserve their rights to raise additional or different objections and defenses to the Order at some later time, or to provide additional information and evidence in support of any position that they may respectively or collectively take in Mr. -

The Big 6 Entertainment Corporations

THE BIG 6 ENTERTAINMENT CORPORATIONS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ News Corporation (abbreviated to News Corp) (NYSE: NWS) is one of the world's largest media conglomerates. Its chief executive officer is Rupert Murdoch, an influential and controversial media tycoon. News Corporation is a public company listed on the New York Stock Exchange and as a secondary listing on the London Stock Exchange (LSE: NCRA). Formerly incorporated in Adelaide, Australia, the company was re- incorporated in the United States state of Delaware after a majority of shareholders approved the move on 12 November 2004. The company is still listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX: NWS). News Corporation's United States headquarters is on Sixth Avenue (Avenue of the Americas) in New York City, in the 1960s-1970s portion of the Rockefeller Center complex. Revenue for the year ended 30 June 2005 was $23.859 billion. This does not include News Corporation's share of the revenue of businesses in which it owns a minority stake, which include two of its most important assets, DirecTV and BSkyB. Almost 70% of the company's sales come from its US businesses. Holdings: Film/TV Production and Distribution 20th Century Fox 20th Century Fox Home 20th Century Fox TV Fox Filmed Entertainment Fox 2000 Blue Sky Studios Fox Searchlight Pictures Fox Animation Studios(defunct) Fox Family World Wide Fox Sports Fox News IGN Entertainment Inc New World Communications Direct TV News Papers/Magazines/Publishers (select) New York Post The Times(Eng) The Sun (Eng) HarperCollins Ecco Press Perennial The Weekly Standard TV Guide Radio/Multimedia (select) Sky Radio Fox Sports Radio News American The Street.com Line One Orbis ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The Walt Disney Company (most commonly known as Disney) (NYSE: DIS) is one of the largest media and entertainment corporations in the world. -

Q2 2005 Viacom Earnings Conference Call Event Date/Time

Conference Call Transcript VIA - Q2 2005 Viacom Earnings Conference Call Event Date/Time: Aug. 04. 2005 / 4:30PM ET Event Duration: 53 min 1 Filed by: Viacom Inc. Pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended Commission File No.: 001-09553 Subject Company: Viacom Inc. - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Operator Good day, everyone, and welcome to the Viacom second-quarter earnings release teleconference. Today's call is being recorded. At this time, I would like to turn the call over to the Senior Vice President of Investor Relations, Mr. Marty Shea. Please go ahead, sir. - -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Marty Shea - Viacom Inc. - EVP, IR Good afternoon, everyone. Thank you for taking time to join us for our conference call today. Joining me for today's discussion will be Sumner Redstone, our Chairman and CEO; Tom Freston and Les Moonves, our Co-Presidents and Co-COOs; and Michael Dolan, Executive Vice President and CFO. Sumner will have some opening remarks and then we will turn the call over to Mike for some specific financial issues. We will then hear from Tom and Les for a discussion of strategy and operations, and then we will open the call up to questions. Let me note that statements on this conference call relating to matters which are not historical facts are forward-looking statements which involve risks and uncertainties and that could cause actual results to differ. Risks and uncertainties are disclosed in Viacom's security filings. This call contains information relating to the proposed separation of Viacom into two publicly traded companies. In connection with that proposed transaction, Viacom intends to file a registration statement on Form S-4 with the SEC. -

C Magazine October 2007 Volume 3/Number 2 Is Published 10 Times/Year by C Publishing, LLC

Naomi Watts a NeW mom oN the a-list the art World’s falleN stars a charmed couple’s CALIFORNIA STYLE mysterious C demise HOmE Special golden state glamOuR mIxing mOdern dESIgN and classic style from SAN FRANCISCO and san dIEgO to THE HOLLYWOOd HILLS Lehman told his realtor, “Take me back to that house with the tree poking through the roof.” OPPOSITE In the entryway, a gold-accented Grosfield House pedestal table echoes the shape of a BDDW mirror hanging above. Los ANgELES AERIE pERCHEd higH IN THE HOLLYWOOd HILLS, NEW YORK TRANSpLANTS Dana Goodyear and BillY lehman’S LOFTY NEST mIxES WORLdLY WHImSY WITH FRESH, CLEAN dESIgN by sally schultheiss photographed by lisa romereiN C 80 C 81 In the living room, a ceramic Jeff Koons terrier vase rests atop a Blackman Cruz glass-and-bronze coffee table, next to a custom sofa from L.A.’s Lawson- Fenning. OPPOSITE The breezy dining room opens to the verdant outdoors, accented with a Kaare Nygaard horse sculpture and a wood credenza from BDDW. f houses embody life stages—the childhood home; September 11th, 2001. “I felt great from the minute I got the bachelor pad; the midlife remodel—then Billy here,” he says. “L.A. is an amazing place to remake your- Lehman and Dana Goodyear’s light-filled residence self.” He bought a mid-century house with good bones, hovering above the Chateau Marmont in the Holly- checked into the Beverly Hilton and began renovations. wood Hills is most definitely the honeymoon suite. There was only one thing holding him back from Everything about the couple’s first shared living taking a full emotional leap into life on the West Coast: space has the blush of new romance and the excite- He had only months earlier met Goodyear, a poet and ment of joining respective passions and interests. -

TELEVISION PARADIGM SHIFTS: BROADCAST to CABLE

PARADIGM SHIFTS in FILM and TELEVISION From Broadcast to Cable/Satellite TV MAJOR TRANSFORMATIONS in Film & Television Update • Exam #1: Thurs 2/28 • No make ups! • Review guide 2/21 • Review session: 2/26 + packets • Today: Major Transformations in Film - TV - Video BROADCAST TV DOMINANCE 1950-1985 •The DOMINANT TV BROADCASTERS! 1. CBS - Columbia Broadcasting System • 20 YEARSTHE DOMINANT NETWORK 1950-1970s • “Eye Network • Ed Sullivan show, The Andy Griffith show, The Beverly Hillbillies. • 60 Minutes • The Late Show -David Letterman • Provides more than 200 programs to its affiliates across the globe • Syndicates and SYNDICATION - 5 SEASONS of a TV Show (package deal) 2. NBC 3. ABC (Wide World of Sports) 1961 4. PBS (1969, Boston Public Broadcasting ACT-- Sesame Street) 5. FOX (1986) Rupert Murdoch (Australian) The Simpsons, The X-Files, Cops, Fox News Leading new network TV series in the United States in the 2016-17 season, by number of viewers (in millions) Most watched new network TV series in the U.S. 2016 20 18 17.64 16 14.41 14.21 14 12 10.83 10.44 9.99 9.8 10 9.39 8.56 8.16 8 Number of viewers in millions inviewers Number of 6 4 2 0 Bull (CBS) Designated This is Us (NBC) Kevin Can Wait Macgyver (CBS) Timeless (NBC) Lethal Weapon The Great Indoors Pure Genius (CBS) Speechless (ABC) Survivor (ABC) (CBS) (FOX) (CBS) Series (network) Note: United States; September 19, 2016 to November 13, 2016; 2 years and older; live and 7-day DVR-delayed viewing Further information regarding this statistic can be found on page 8. -

The Evolution of MTV Music Programs an Analysis of the MTV Artists Program Huiming Zhang

The Evolution of MTV Music Programs An Analysis of the MTV Artists Program A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Huiming Zhang in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science August 2014 © Copyright 2014 Huiming Zhang. All Rights Reserved i Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................... ii Abstract ........................................................................................................................ iii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 Background and Need ........................................................................................................... 5 Purpose of the Study ........................................................................................................... 10 Research Questions ............................................................................................................. 11 CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 12 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 12 Body of the Review ............................................................................................................