An Introduction to the Gospel of Matthew Trinity Cathedral Matthew Groups by the Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L E N T E N P R O G R a M 2 0

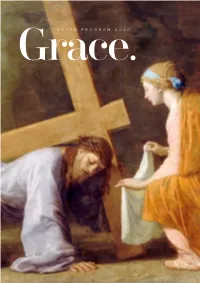

LENTEN PROGRAM 2020 Grace. 12 TheFIRST Temptation. SUNDAY OF LENT CONTENTS 22 The SECONDTransfiguration. SUNDAY OF LENT 4 Leading the weekly sessions 5 Contributor biographies Sunday reflections 32 Fr Christopher G Sarkis The Samaritan Sr Anastasia Reeves OP THIRD SUNDAYwoman. OF LENT Mgr Graham Schmitzer 6 Contributor biographies Weekday reflections 42 Sr Susanna Edmunds OP Healing the Fr Damian Ference blind man. Peter Gilmore FOURTH SUNDAY OF LENT Michael “Gomer” Gormley Sr Mary Helen Hill OP Fr Antony Jukes OFM Sr Elena Marie Piteo OP 53 Sr Magdalen Mather OSB Darren McDowell RaisingFIFTH SUNDAY Lazarus. OF LENT Trish McCarthy Matthew Ockinga Fr Chris Pietraszko Mother Hilda Scott OSB 62 Professor Eleonore Stump Michelle Vass ThePALM Passion. SUNDAY 74 HeEASTER is risen. SUNDAY 3 The Temptation.FIRST SUNDAY OF LENT 4 ARTWORK REFLECTION He was born of a poor family, and his mother had hoped he would become a priest. He was involved in the insurrection of 1848 which erupted in Naples. After his death, he was labelled as one of the warrior artists of Italy. Is this reflected in the painting we are contemplating—a battle? The landscape is desert, not a slice of green to be seen. Christ seems to be in a completely relaxed mode, an attitude of prayer, engrossed in conversation with his Father. Fasting has not emaciated him. He seems completely in control. The Temptation of Christ But, on the left is the Tempter. In Latin, “left” is Domenico Morelli (1823–1901) sinistra, from which we get our word “sinister”. It “The Temptation of Christ”, c. -

Matthew 25 Bible Study the Gospel and Inclusivity

Matthew 25 Bible Study The Gospel and Inclusivity Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Presbyterian Mission The Gospel and Inclusivity A Matthew 25 Bible Study by Rev. Samuel Son If you don’t know the kind of person I am and I don’t know the kind of person you are a pattern that others made may prevail in the world and following the wrong god home we may miss our star. – William Stafford, “A Ritual to Read to Each Other” I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting the one who called you in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel—not that there is another gospel, but there are some who are confusing you and want to pervert the gospel of Christ. – Paul, “Letter to the Galatians” The big problem that confronts Christianity is not Christ’s enemies. Persecution has never done much harm to the inner life of the Church as such. The real religious problem exists in the souls of those of us who in their hearts believe in God, and who recognize their obligation to love Him and serve Him – yet do not! – Thomas Merton, in “Ascent to Truth” Contents How to Use This Study................................................................................................ 4 Section 1 ......................................................................................................................5 Purpose of this Study ...............................................................................................5 My Journey of Rediscovering the Gospel ..................................................................5 How Did We Get Here? -

Small Group Study Guide Contents

SMALL GROUP STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS Welcome 4 About This Guide 6 Session 1 9 Blessed are the poor in spirit Session 2 17 Blessed are those who mourn Session 3 25 Blessed are the meek Session 4 33 Blessed are those who hunger Copyright + Acknowledgments Session 5 41 Blessed are the merciful Written by Janet Branham, Bob Hayes, Kristen Shunk, and Chris Walker Session 6 49 Blessed are the pure in heart Edited by Tanya Emley Session 7 57 Blessed are the peacemakers Copyright © 2019 Ward Church, all rights reserved Session 8 65 Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations Blessed are those who are persecuted are from the New International Version 2011 Appendix A 72 Group Agreement Production by Greenman’s Printing and Imaging Appendix B 74 Group Calendar Appendix C 76 Contact Information 2 FALL 2019 STUDY GUIDE 3 WELCOME Welcome to our eight-week series on the Beatitudes! We’ve worked on The Beatitudes remind us that things aren’t always what they seem. this curriculum for months and are so excited to put it in your hands! Things that seem upside down in the world are made right side up in God’s economy. These teachings of Jesus provide comfort and assurance We invite you to travel back in time almost two millennia and sit at the for sure, but those willing to take His words to heart will find plenty of feet of Jesus. Learn with us from the Master, the greatest teacher, the challenging ideas that prompt life change. You see, this journey isn’t just greatest man who ever lived. -

Authentic Prayer” Matthew 6:7-13, 7:7-11

3-4-18 Pastor Tom “Authentic Prayer” Matthew 6:7-13, 7:7-11 Matthew 6:7-13 - And when you pray, do not keep on babbling like pagans, for they think they will be heard because of their many words. 8 Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him. 9 “This, then, is how you should pray: “‘Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name, 10 your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. 11 Give us today our daily bread. 12 And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. 13 And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one.’ Skip ahead to Matthew 7:7-11 - Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you.8 For everyone who asks receives; the one who seeks finds; and to the one who knocks, the door will be opened. 9 “Which of you, if your son asks for bread, will give him a stone? 10 Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a snake? 11 If you, then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good gifts to those who ask him! Finally! We’ve been going through the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus is telling us everything we need to do. But this week, we finally get something out of this whole Christianity thing! He says if we just ask, seek, and knock, we will receive, find, and the door will be opened for us! So here comes the big question: What are you gonna ask for? The guy who turns water into wine, who heals the sick, raises the dead, and does a ton of other miracles says, “ask and it will be given to you.” Man, “Well, Jesus, where do I start? Car, vacation, house… I guess I should throw in world peace, too…” This actually reminds me of a commercial from a few years ago where some people got whatever they asked for. -

PDF Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of MARK Part of the Holy Bible A Translation From the Greek by David Robert Palmer https://bibletranslation.ws/palmer-translation/ ipfs://drpbible.x ipfs://ebibles.x To get printed edtions on Amazon go here: http://bit.ly/PrintPostWS With Footnotes and Endnotes by David Robert Palmer July 23, 2021 Edition (First Edition was March 1998) You do not need anyone's permission to quote from, store, print, photocopy, re-format or publish this document. Just do not change the text. If you quote it, you might put (DRP) after your quotation if you like. The textual variant data in my footnote apparatus are gathered from the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament 3rd Edition (making adjustments for outdated data therein); the 4th Edition UBS GNT, the UBS Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, ed. Metzger; the NA27 GNT; Swanson’s Gospels apparatus; the online Münster Institute transcripts, and from Wieland Willker’s excellent online textual commentary on the Gospels. The readings for Φ (043) I obtained myself from Batiffol, Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. PAG E 1 The Good News According to MARK Chapter 1 John the Baptizer Prepares the Way 1The beginning of the good news about Jesus Christ, the Son of God.1 2As2 it is written in the prophets: 3 "Behold, I am sending my messenger before your face, who will prepare your way," 3"a voice of one calling in the wilderness, 'Prepare the way for the Lord, make the paths straight for him,'4" 4so5 John the Baptizer appeared in the wilderness, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. -

JESUS QUESTIONS the PHARISEES Whose Son Is Christ

JESUS QUESTIONS THE PHARISEES Micah prophesied that the Messiah would be born in Whose Son Is Christ? Bethlehem and come from the clan of David (Micah 5:2). Matthew 22:41-46 Ezekiel prophesied the reuniting of Israel into one nation I. THE INQUIRING QUESTION: (vs. 41-42a)...a probing question following their division (Israel and Judah) and that there would Now while the Pharisees were gathered together, Jesus asked be one king for all of them and that king would be from His servant David (Ezekiel 21-25). them a question: “What do you think about the Christ, whose son is He?” (vs. 41-42a)... Throughout his gospel, Matthew focused on Jesus being the Son of David: After conclusively answering the three questions that the Jewish leaders had asked designed to entrap Him (Matthew 22:15-40)... Begins with the genealogy (Matthew 1:6; Luke 3:31). Jesus continued to teach in the Temple where He had been since Matthew recorded Jesus being hailed by various groups as the early that morning (Matthew 21:23). Son of David throughout His earthly ministry. After all that has previously taken place that morning, He then took At the Triumphal Entry the people shouted and called Him, the opportunity to ask them a question about the Christ. Notice Son of David (Matthew 21:9). that He didn’t ask this question directly about Himself...instead He asked it in the second person. Even though He had often declared The two blind men in Galilee cried out, “Have mercy on us, Son of David” (Matthew 9:27). -

September 20, 2020

September 20, 2020 The mission of The First Presbyterian Church in Germantown is to reflect the loving presence of Christ as we serve others faithfully, worship God joyfully and share life together in a diverse and generous community. September 20, 2020 "Above all the grace and gifts that Christ gives to his beloved is that of overcoming self." - Francis of Assisi ORDER OF MORNING WORSHIP AT 10:00 AM GATHERING AS GOD’S FAMILY Prelude: And Can it Be? Dan Forrest trans. Isaac Dae Young Welcome and Announcements †*Call to Worship Rev. Kevin Porter One: Coming from places that have seen better days, Many: God bids us to celebrate this day, a day full of new possibilities. One: Coming with our breath taken away by grief, Many: the Holy Spirit breathes new life within us, renewing our connection with God and with one another. One: Coming to worship seeking a hope that will endure, Many: Christ unbinds the fetters that hold us in death, speaking in word and sacrament, and building community for holy service. One: Coming to worship seeking a hope that will endure, All: Coming together even as we are apart. Coming to worship the Lord! *Hymn 464: Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee FAITHFULNESS Joyful, joyful, we adore Thee, God of glory, Lord of love; Hearts unfold like flowers before Thee, Opening to the sun above, Melt the clouds of sin and sadness; Drive the dark of doubt away; Giver of immortal gladness, Fill us with the light of day! All Thy works with joy surround Thee, Earth and heaven reflect Thy rays, Stars and angels sing around Thee, Center of unbroken praise; Field and forest, vale and mountain, Flowery meadow, flashing sea, Chanting bird and flowing fountain Call us to rejoice in Thee. -

The Temptation of Christ

The Temptation of Christ REDEMPTION SERIES # 2 Ellen G. White 1877 Contents Confrontation in the Desert Adam and Eve and their Eden home The Test of Probation Paradise Lost. Plan of Redemption Sacrificial Offerings Appetite and Passion A Threat to Satan's Kingdom The Temptation Christ as a Second Adam Terrible Effects of Sin upon Man The First Temptation of Christ Significance of the Test Christ did no Miracle for Himself He Parleyed not with Temptation Victory through Christ The Second Temptation The Sin of Presumption Christ our Hope and Example The Third Temptation Christ's Temptation Ended Christian Temperance. Self-indulgence in Religion's Garb More Than One Fall. Health and Happiness. Strange Fire. Presumptuous Rashness and Intelligent Faith. Spiritism Character Development Confrontation in the Desert After the baptism of Jesus in Jordan He was led by the Spirit into the wilderness, to be tempted of the devil. When He had come up out of the water, He bowed upon Jordan's banks and pleaded with the great Eternal for strength to endure the conflict with the fallen foe. The opening of the heavens and the descent of the excellent glory attested His divine character. The voice from the Father declared the close relation of Christ to His Infinite Majesty: "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased." The mission of Christ was soon to begin. But He must first withdraw from the busy scenes of life to a desolate wilderness for the express purpose of bearing the threefold test of temptation in behalf of those He had come to redeem. -

King of Kings (Matthew 2)

washington,wa s h i n g t o n , dcd c KING OF KINGS Epiphany 2019 Matthew 2:1-12 Dan Claire The story of the Wise Men is the sequel to Matthew’s account of the birth of Jesus, and it begins with two important details that weren’t mentioned in chapter one: namely, the place and the time. Matthew writes: “Now after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the east came to Jerusalem.” (2:1) The place and the time of a story usually aren’t all that exciting, but if it’s a good story, these details are often essential for understanding what the story is all about. That’s certainly the case in Matthew’s story. The place where Jesus was born, Matthew tells us, was Bethlehem–not Jerusalem. Isn’t it odd that Matthew didn’t mention this earlier, when he told the story of Jesus' birth? Matthew was saving this detail until now, until the story of the Wise Men. Most people would have expected the new king to be born in the royal palace in Jerusalem, ~5 miles to the north, and that’s exactly where the Wise Men looked first. They arrived and asked, “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.” (2:2) But Jesus wasn’t there. He was in the City of David, in Bethlehem and not in Jerusalem. -

Gospel of Mark Study Guide

Gospel of Mark Study Guide Biblical scholars mostly believe that the Gospel of Mark to be the first of the four Gospels written and is the shortest of the four Gospels, however the precise date of when it was written is not definitely known, but thought to be around 60-75 CE. Scholars generally agree that it was written for a Roman (Latin) audience as evidenced by his use of Latin terms such as centurio, quadrans, flagellare, speculator, census, sextarius, and praetorium. This idea of writing to a Roman reader is based on the thinking that to the hard working and accomplishment-oriented Romans, Mark emphasizes Jesus as God’s servant as a Roman reader would relate better to the pedigree of a servant. While Mark was not one of the twelve original disciples, Church tradition has that much of the Gospel of Mark is taken from his time as a disciple and scribe of the Apostle Peter. This is based on several things: 1. His narrative is direct and simple with many vivid touches which have the feel of an eyewitness. 2. In the letters of Peter he refers to Mark as, “Mark, my son.” (1 Peter 5:13) and indicates that Mark was with him. 3. Peter spoke Aramaic and Mark uses quite a few Aramaic phrases like, Boanerges, Talitha Cumi, Korban and Ephphatha. 4. St Clement of Alexandria in his letter to Theodore (circa 175-215 CE) writes as much; As for Mark, then, during Peter's stay in Rome he wrote an account of the Lord's doings, not, however, declaring all of them, nor yet hinting at the secret ones, but selecting what he thought most useful for increasing the faith of those who were being instructed. -

Sermon on the Mount Commentaries

Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Sermon on the Mount Study Guide: Questions and Answers Sermon on the Mount Commentary Matthew 5-7 Table of Contents Verse by Verse In Depth Commentary Conservative, Literal, Evangelical Sermon on the Mount Commentary Matthew 5:1-11 The Beatitudes Matthew 5:1 Matthew 5:2 Matthew 5:3 Matthew 5:4 Matthew 5:5 Matthew 5:6 Matthew 5:7 Matthew 5:8 Matthew 5:9 Matthew 5:10 Matthew 5:11 Matthew 5:12 Sermon on the Mount Commentary Matthew 5:13-16 Salt and Light Matthew 5:13 Matthew 5:14 Matthew 5:15 Matthew 5:16 Sermon on the Mount Commentary Matthew 5:17-20 Jesus Teaches on Righteousness Necessary to Enter The Kingdom of Heaven Matthew 5:17 Matthew 5:18 Matthew 5:19 Matthew 5:20 Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Matthew 5:21-22 Jesus Teaches on Murder and Anger Matthew 5:21 Matthew 5:22 Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Matthew 5:23-26 Jesus Teaches on Reconciliation Matthew 5:23 Matthew 5:24 Matthew 5:25 Matthew 5:26 Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Matthew 5:27-30 Jesus Teaches on Adultery Matthew 5:27 Matthew 5:28 Matthew 5:29 Matthew 5:30 Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Matthew 5:31-32 Jesus Teaches on Divorce Matthew 5:31 Matthew 5:32 Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Matthew 5:33-37 Jesus Teaches on Oaths and Vows Matthew 5:33 Matthew 5:34 Matthew 5:35 Matthew 5:36 Matthew 5:37 Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Matthew 5:38-42 Jesus Teaches on Revenge and Non-Resistance (An Eye for an Eye) Matthew 5:38 Matthew 5:39 Matthew 5:40 Matthew 5:41 Matthew 5:42 Sermon on the Mount Commentaries Matthew 5:43-48 Jesus Teaches -

The Earliest Magdalene: Varied Portrayals in Early Gospel Narratives

Chapter 1 The Earliest Magdalene: Varied Portrayals in Early Gospel Narratives Edmondo Lupieri In the early writings produced by the followers of Jesus, Mary Magdalene is connected with key events in the narrative regarding Jesus: his death on the cross, his burial, and his resurrection.1 At first sight, her figure seems to grow in importance through time. Her name and figure, indeed, are completely ab- sent from the oldest extant texts written by a follower of Jesus, the authentic letters of Paul.2 This is particularly striking, since 1 Cor 15:5–8 contains the ear- liest known series of witnesses to the resurrection, but only men are named specifically.3 1 All translations are the author’s. The Greek text of the New Testament is from Eberhard Nestle et al., eds., Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th ed. (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1993). 2 This phenomenon seems to parallel the minimal importance of the mother of Jesus in Paul’s letters. He mentions her only once and indirectly, when stressing that Jesus was born “of a woman” and “under the Law” (Gal 4:4). Besides using her existence to reaffirm the humanity (and Jewishness) of Jesus (for a similar use of a similar expression to describe the humanity of John the Baptist, see Luke 7:28 / Matt 11:11), Paul does not seem to care about who that “woman” was. This does not mean that Paul is particularly uninterested in Mary Magdalene or in Jesus’s mother, but that generally in his letters Paul does not seem to be interested in any detail regarding the earthly life of Jesus or in the persons who were around him when he was in his human flesh (see further n.