Musical Resonances Between Argyll and Antrim Stuart Eydmann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Frommer's Scotland 8Th Edition

Scotland 8th Edition by Darwin Porter & Danforth Prince Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Authors Darwin Porter has covered Scotland since the beginning of his travel-writing career as author of Frommer’s England & Scotland. Since 1982, he has been joined in his efforts by Danforth Prince, formerly of the Paris Bureau of the New York Times. Together, they’ve written numerous best-selling Frommer’s guides—notably to England, France, and Italy. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Carradale to Campbeltown

Carradale to Campbeltown 22 miles, 35.4 km allow 8-10 hours – it is recommended that you walk from Carradale back to Campbeltown It is possible to split this section by walking down to the road at Saddell, where you can visit the Abbey, Castle and beach, before catching a bus No Carradale Service Sat or Sun Stone carvings at take a walk on the wild side From Campbeltown Saddel Abbey Carradale to Campbeltown Secon 5 Out (No.300/445) Depart Campbeltown, Bus Terminal near Aqualibrium, 09.30 arrive Carradale Carradale to Dr's Surgery 10.07 Campbeltown Campbeltown to Carradale Return (Nos. 300/445) Depart Carradale outside Dr's Surgery, 16.52 / 18.17 arrive Campbeltown 17.25 / 18.55 EXPLORECarradale, Torrisdale Timetables can be viewed at bus stops or online and Saddell www.westcoastmotors.co.uk www.travelinescotland.com 2020 - Check all bus times with operator Campbeltown Cinema and cafe Taxis available in Campbeltown Taxis – the rocky coastlineENJOY at Waterfoot, woodland walks though Torrisdale Refreshments Carradale - there is a tea room at the Network Carradale to Campbeltown estate and the forest track to Centre just beside the way and there are hotels in Loch Lussa before descending to the village. Campbeltown – well served with cafes southwards over Waterfoots rocky Campbeltown and hotels, open year round coastline pass Torrisdale Castle Estate Please ensure you have sufficient food & water - with Beinn an Tuirc Gin Disllery no shops between Carradale and Campbeltown descend to Ifferdale and Saddell James T M Towill (cc-by-sa/2.0) James T M Towill Castle through the forest around DISCOVER ckwo Lussa Loch, descend to Campbeltown Bein an Tuirc Disllery, Saddell r © Photo du th ( via cc with its Picture House, swimming Abbey and catch sight of the yl -b s y -s pool and gym and accommodaon Antony Gormley figure, Grip, © a o / t 2 looking out to sea at Saddell bay o . -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

Traditional Fiddle Music of the Scottish Borders

CD Included Traditional Fiddle Music of the Scottish Borders from the playing of Tom Hughes of Jedburgh Sixty tunes from Tom’s repertoire inherited from a rich, regional family tradition fully transcribed with an analysis of Tom’s old traditional style. by Peter Shepheard Traditional Fiddle Music of the Scottish Borders from the playing of Tom Hughes of Jedburgh A Player’s Guide to Regional Style Bowing Techniques Repertoire and Dances Music transcribed from sound and video recordings of Tom Hughes and other Border musicians by Peter Shepheard scotlandsmusic 13 Upper Breakish Isle of Skye IV42 8PY . 13 Breacais Ard An t-Eilean Sgitheanach Alba UK Taigh na Teud www.scotlandsmusic.com • Springthyme Music www.springthyme.co.uk [email protected] www.scotlandsmusic.com Taigh na Teud / Scotland’s Music & Springthyme Music ISBN 978-1-906804-80-0 Library Edition (Perfect Bound) ISBN 978-1-906804-78-7 Performer’s Edition (Spiral Bound) ISBN 978-1-906804-79-4 eBook (Download) First published © 2015 Taigh na Teud Music Publishers 13 Upper Breakish, Isle of Skye IV42 8PY www.scotlandsmusic.com [email protected] Springthyme Records/ Springthyme Music Balmalcolm House, Balmalcolm, Cupar, Fife KY15 7TJ www.springthyme.co.uk The rights of the author have been asserted Copyright © 2015 Peter Shepheard Parts of this work have been previously published by Springthyme Records/ Springthyme Music © 1981 A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. The writer and publisher acknowledge support from the National Lottery through Creative Scotland towards the writing and publication of this title. All Rights Reserved. -

Join Us Aboard the Lady of Avenel for Sessions and Sail 2020 – Argyll

Join us aboard the Lady of Avenel for Sessions and Sail 2020 – Argyll This two-masted, Brigantine-rigged tall ship will be your home for the week as we step aboard in Oban and sail the waters south of Mull and the coast of Argyll and the islands. The ship will be your base for a voyage of exploration and music with sessions, workshops, sailing and more. See the spectacular Paps of Jura from the sea, feel the tide course through the Sound of Islay, visit Colonsay, Gigha and more. You will learn tunes from the rich local tradition under the guidance of some of Scotland’s best musicians in the bright saloon aboard Lady of Avenel; later, we will walk ashore to a local pub or village hall to play sessions with local musicians and meet the communities. Throughout the trip we will enjoy locally sourced food, beautifully prepared by our on-board chef. Some of our likely destinations are outlined overleaf. We look forward to having you join us! 1 Sessions and Sail - Nisbet Marine Services Ltd, Lingarth, Cullivoe, Yell, Shetland ZE2 9DD Tel: +44 (0)7775761149 Email: [email protected] Web: www.sessionsandsail.com If you are a keen musician playing at any level - whether beginner, intermediate or expert - with an interest in the traditional and folk music of Scotland, this trip is for you. No sailing experience is necessary, but those keen to participate will be encouraged to join in the sailing of the ship should they wish to, whether steering, helping set and trim the sails, or even climbing the mast for the finest view of all. -

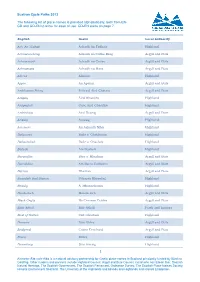

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

The History of the Celtic Language May Be Turned To

'^^'& msw 6iW. l(o?^ )^. HISTORY CELTIC LANGUAGE; WHEKEIX IT IS SHOWN TO BE BASED UPON NATURAL PRINCIPLES, AXD, ELEMENTARILY CONSIDERED, CONTEMPORANEOUS WITH THE INFANCY OF THE HUMAN FAMILY : LIZEWISE SHOWING ITS IMPORTANCE IN ORDER TO THE PROPER UNDERSTANDING OF THE CLASSICS, INCLUDING THE SACRED TEXT, THE HIEROGLYPHICS, THE CABALA, ETC. ETC. BY L. MACLEAN, F.O.S, kuthnr of" Historical Account of lona," " Sketches of St Kilda," &c. Sec. LONDON: SMITH, ELDER, and CO.; EDINBURGH: M'LACHLAN, STEWART, and CO. GLASGOW: DUGALD MOORE. MDCCCXL. " IT CONTAINS MANY TRUTHS WHICH ARE ASTOUNDING, AND AT WHICH THE IGNORANT MAY SNEER; BUT THAT WILL NOT TAKE PROM THEIR ACCURACY. "_SEB SIR WILLIAM BETHAM's LETTER TO THE AUTHOR IN REFERENCE TO THE GAELIC EDITION. " WORDS ARE THE DAUGHTERS OF EARTH—THINGS ARE THE SONS OF HEAVEN."—SAMUEL JOHNSON, GLASGOW: — F.nWAKi) KHII.I., I'Hl NTER TO THE U M VERSITV. ^' D IBtKication^ RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR ROBERT PEEL, baronet, m.p. Sir, An ardent admirer of your character, public and private, I feel proud of the permission you have kindly granted me to Dedicate to you this humble Work. The highest and most noble privilege of great men is the opportunity their station affords them of fostering the Fine Arts, and amplifying the boundaries of useful knowledge. That this spirit animates your bosom, each successive day is adding proof: nor is the fact IV DEDICATION. unknown, that whilst your breast glows with the fire of the patriot, beautifully harmonizing with the taste of the scholar, your energies are likewise engaged on the side of that pure religion of your fathers, with which your own mind has been so early imbued, and which, joined with Education, is, as has properly been said, " the cheapest defence of a nation;" as it is the only solid foundation whereon to build our hopes of bliss in a world to come. -

3•5 Carradale to Campbeltown 51 55 Following the Course of Allt Na Caillich

• The path drops steeply. At a junction on the right, continue downhill, generally 3•5 Carradale to Campbeltown 51 55 following the course of Allt na Caillich. Eventually, turn right along a vehicle track. Distance 199 miles (32.1 km) • Just past the playing field, there’s a choice of route: bear left and you soon come to Terrain roadside and woodland paths, minor roads then shoreline rock-hopping; forest roads, a parking area after which it’s only 50 m to the B879 road where you can turn left for lengthy forest road walk from Lussa Loch to Corrylach; then tarmac in Campbeltown the village of Carradale and some of its facilities: see below. Grade stiff ascent from Torrisdale and descent to Ifferdale, then tough climb to 285 m/935 ft before dropping down to Lussa Loch and gentler gradients • Otherwise, the Way continues for ¾ mile (over 1 km) along the forest track, Food & drink none between Carradale and Campbeltown descending to the B879 at the Network Carradale Heritage Centre and excellent tea Summary a very long and demanding, but generally rewarding day; tide awareness essential room. The shop and other facilities are about 200 m to the right. for Carradale Bay; varied views from forest and minor roads Carradale (population 400) lies at the head of Carradale Bay on the Kilbrannan Sound. 5.8 Ifferdale Cottage 2.8 3.0 Lussa Loch 4.7 Calliburn 3.6 . Its name reflects Norse origins and means ‘brush-wood valley’. There’s a limited Carradale 9 3 4 5 4 9 Strathduie Water 7 6 5 8 Campbeltown range of accommodation, a small shop, bakery, and a bus stop. -

Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications 12Th July 2019.Pdf

Weekly Planning list for 12 July 2019 Page 1 Argyll and Bute Council Planning Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week ending 12 July 2019 12/7/2019 9:14 Weekly Planning list for 12 July 2019 Page 2 Bute and Cowal Reference: 19/00955/PP Officer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 08 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Installation of replacement windows Location: 3Wellpar k Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute, PA20 9JY Applicant: Miss J McCusker 3Wellpar k Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute , PA20 9JY Ag ent: Kenneth Wotherspoon 1Holm Street, Crossford, Carluke, ML8 5GR Development Type: N01 - Householder developments Grid Ref: 210598 - 665259 Reference: 19/01273/PP Officer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 08 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Erection of timber outdoor classroom Location: Apple Tree Nursery, 10MackinlayStreet, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute,PA20 0AY Applicant: Apple Tree NurseryLimited Apple Tree Nursery, 10MackinleyStreet, Rothesay, Scotland, PA20 0AY Ag ent: James Wilson Spr ingbank, 7Chapelhill Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,PA20 0BJ Development Type: N10B - Other developments - Local Grid Ref: 208309 - 665074 Reference: 19/01292/PP Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 07 - Dunoon Community Council: Dunoon Community Council Proposal: Installation of 1 x 7kW dual outlet vehicle charging unit, erec- tion of protection barriers and for mation of 2 appropriately signed bays within -

300 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

300 bus time schedule & line map 300 Campbeltown - Carradale View In Website Mode The 300 bus line (Campbeltown - Carradale) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Campbeltown: 4:45 PM (2) Carradale: 7:10 AM - 9:30 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 300 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 300 bus arriving. Direction: Campbeltown 300 bus Time Schedule 11 stops Campbeltown Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:45 PM Pier, Carradale Tuesday 4:45 PM Post O∆ce, Carradale Airds, Scotland Wednesday 4:45 PM Port Righ Road End, Carradale Thursday 4:45 PM Friday 4:45 PM Surgery, Carradale Saturday Not Operational Lodge, Torrisdale Millers Park, Saddell Road End, Ugadale 300 bus Info Direction: Campbeltown Forestry Road End, Ballochgair Stops: 11 Trip Duration: 40 min Bus Shelter, Peninver Line Summary: Pier, Carradale, Post O∆ce, Carradale, Port Righ Road End, Carradale, Surgery, Carradale, Lodge, Torrisdale, Millers Park, Saddell, Auchinlee, Campbeltown Road End, Ugadale, Forestry Road End, Ballochgair, Bus Shelter, Peninver, Auchinlee, Campbeltown, Bus Bus Terminus, Campbeltown Terminus, Campbeltown Direction: Carradale 300 bus Time Schedule 17 stops Carradale Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:10 AM - 9:30 AM Bus Terminus, Campbeltown Tuesday 7:10 AM - 9:30 AM Lorne And Lowland Church, Campbeltown Wednesday 7:10 AM - 9:30 AM Fiddlers Inn, Campbeltown Thursday 7:10 AM - 9:30 AM Lochend Street, Campbeltown Friday 7:10 AM - 9:30 AM Tesco,