Anterior Segment Inflammation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre Feasibility Report for Manufacturing of Apis

Pre Feasibility Report For Manufacturing of APIs Cipla Limited Plot No. M12 & M14, Misc. Zone, Phase II, Sector III, Indore SEZ, Pithampur, District Dhar (M.P). - 454775 1 1. IDENTIFICATION OF PROJECT AND PROJECT PROPONENT: CIPLA Ltd is established in the year 1935 as a listed Public Limited Company. CIPLA is engaged in manufacturing of Bulk Drugs and Formulations of wide range of products in the form of tablets, injections, inhalers, capsules, ointment, powder, topical preparations, liquid, syrup drops, sprays, gels, suppositories etc. The company is having its registered office at Mumbai Central, Mumbai – 400 008. 80 years later, the company has become a front runner in the pharmaceutical industry, wielding the latest technology to combat disease and suffering in many ways, touching the lives of thousands the world over.The company’s products are manufactured in 25 state-of- art units. The company is having its manufacturing facilities at following locations: Locations Product Category Vikhroli- Mumbai R&D Virgonagar (Bangalore) Bulk Drugs and Formulations Bommasandra (Bangalore) Bulk Drug Patalganga Bulk Drugs and Formulations Kurkumbh Bulk Drugs and Formulations Goa Formulations Baddi Formulations Sikkim Formulations Indore Formulations The company is having well defined board of directors followed by managerial and technical team looking after entire operation. Management Council- 1. Mr. Umang Vohra - Managing Director and Global Chief Executive Officer 2. Mr. PrabirJha - Global Chief People Officer 3. Mr. KedarUpadhye - Global Chief Financial Officer 4. Dr. Ranjana Pathak - Global Head – Quality 5. Geena Malhotra - Global Head - Integrated Product Development 6. Mr. Raju Subramanyam – Global Head - Operations List of Key Executives- 1. -

Formulary Updates Effective January 1, 2021

Formulary Updates Effective January 1, 2021 Dear Valued Client, Please see the following lists of formulary updates that will apply to the HometownRx Formulary effective January 1 st , 2021. As the competition among clinically similar products increases, our formulary strategy enables us to prefer safe, proven medication alternatives and lower costs without negatively impacting member choice or access. Please note: Not all drugs listed may be covered under your prescription drug benefit. Certain drugs may have specific restrictions or special copay requirements depending on your plan. The formulary alternatives listed are examples of selected alternatives that are on the formulary. Other alternatives may be available. Members on a medication that will no longer be covered may want to talk to their healthcare providers about other options. Medications that do not have alternatives will be available at 100% member coinsurance . Preferred to Non -Preferred Tier Drug Disease State /Drug Class Preferred Alternatives ALREX Eye inflammation loteprednol (generic for LOTEMAX) APRISO 1 Gastrointestinal agent mesalamine (generic for APRISO) BEPREVE Eye allergies azelastine (generic for OPTIVAR) CIPRODEX 1 Ear inflammation ciprofloxacin-dexamethasone (generic for CIPRODEX) COLCRYS 1 Gout colchicine (generic for COLCRYS) FIRST -LANSOPRAZOLE Gastrointestinal agent Over-the-counter lansoprazole without a prescription FIRST -MOUTHWASH BLM Mouth inflammation lidocaine 2% viscous solution (XYLOCAINE) LOTEMAX 1 Eye inflammation loteprednol etabonate (generic -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

Wednesday, June 12, 2019 4:00Pm

Wednesday, June 12, 2019 4:00pm Oklahoma Health Care Authority 4345 N. Lincoln Blvd. Oklahoma City, OK 73105 The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center COLLEGE OF PHARMACY PHARMACY MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS MEMORANDUM TO: Drug Utilization Review (DUR) Board Members FROM: Melissa Abbott, Pharm.D. SUBJECT: Packet Contents for DUR Board Meeting – June 12, 2019 DATE: June 5, 2019 Note: The DUR Board will meet at 4:00pm. The meeting will be held at 4345 N. Lincoln Blvd. Enclosed are the following items related to the June meeting. Material is arranged in order of the agenda. Call to Order Public Comment Forum Action Item – Approval of DUR Board Meeting Minutes – Appendix A Update on Medication Coverage Authorization Unit/Use of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor (ACEI)/ Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (ARB) Therapy in Patients with Diabetes and Hypertension (HTN) Mailing Update – Appendix B Action Item – Vote to Prior Authorize Aldurazyme® (Laronidase) and Naglazyme® (Galsulfase) – Appendix C Action Item – Vote to Prior Authorize Plenvu® [Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-3350/Sodium Ascorbate/Sodium Sulfate/Ascorbic Acid/Sodium Chloride/Potassium Chloride] – Appendix D Action Item – Vote to Prior Authorize Consensi® (Amlodipine/Celecoxib) and Kapspargo™ Sprinkle [Metoprolol Succinate Extended-Release (ER)] – Appendix E Action Item – Vote to Update the Prior Authorization Criteria For H.P. Acthar® Gel (Repository Corticotropin Injection) – Appendix F Action Item – Vote to Prior Authorize Fulphila® (Pegfilgrastim-jmdb), Nivestym™ (Filgrastim-aafi), -

By Ron Melton, Od, and Randall Thomas, Od, Mph

BY RON MELTON, OD, AND RANDALL THOMAS, OD, MPH Supported by an Unrestricted Grant from FC_DG0515_me.indd 4 4/27/15 3:33 PM Why Drug Costs are Skyrocketing By Agustin Gonzalez, OD drug shortage list in 2012.4,5 A tab- a price decrease while one-third let that cost as little as 6 cents early noted price increases. Only 6% of or the last few years, patients in 2012 was being retailed at $4+ the medications doubled in cost, have complained of price by November 2013—when it was and only about 12 medications and F increases and even shortages even available.5 dosages had increases in cost by 20 of some medications, which has How did this increase happen? times or more.8 frustrated many clinicians. Unfortu- The costly 12 were represented nately, price increases and inflation Reasons for the Rise as various forms and/or dosages of are a common problem affecting Analysts and politicians have cited just four molecules. The leader in everyday life, and medications are many factors—including greed, cost was doxycycline, followed by no exception.1,2 But more recently, FDA regulations and the Afford- the asthma medication albuterol. In shortages of doxycycline and the in- able Care Act—but industry experts the ophthalmic arena, doxycycline creased cost of generic prednisolone attribute price increases for these was not alone; a tube of erythro- formulations have perhaps hit eye medications to consolidation, short- mycin ointment that retailed for $4 care harder than any other medical ages in ingredients and decreased in 2012 cost more than $25 by late group.3 manufacturing.6, 7 2013. -

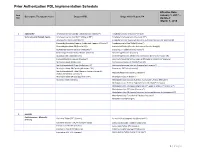

Prior Authorization PDL Implementation Schedule

Prior Authorization PDL Implementation Schedule Effective Date: Item January 1, 2017 – Descriptive Therapeutic Class Drugs on PDL Drugs which Require PA Nbr Updated: March 1, 2018 1 ADD/ADHD Amphetamine Salt Combo Tablet ( Generic Adderall®) Amphetamine ODT (Adzenys® XR ODT) Stimulants and Related Agents Amphetamine Salt Combo ER (Adderall XR®) Amphetamine Suspension (Dyanavel XR®) Atomoxetine Capsule (Strattera®) Amphetamine Salt Combo ER (Generic; Authorized Generic for Adderall XR) Dexmethylphenidate (Generic; Authorized Generic of Focalin®) Amphetamine Sulfate Tablet (Evekeo®) Dexmethylphenidate ER (Focalin XR®) Armodafinil Tablet (Generic; Authorized Generic; Nuvigil®) Dextroamphetamine Solution (Procentra®) Clonidine ER Tablet (Generic; Kapvay®) Dextroamphetamine Sulfate Tablet (Generic) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin®) Guanfacine ER Tablet (Generic) Dexmethylphenidate XR (Generic; Authorized Generic for Focalin XR) Lisdexamfetamine Capsule (Vyvanse®) Dextroamphetamine Sulfate Capsule ER (Generic; Dexedrine®Spansule) Methylphenidate IR (Generic) Dextroamphetamine IR Tablet (Zenzedi®) Methylphenidate ER Chew (Quillichew ER®) Dextroamphetamine Solution (Generic for Procentra®) Methylphenidate ER Capsule (Metadate CD®) Guanfacine ER Tablet (Intuniv®) Methylphenidate ER Tablet (Generic; Generic Concerta®; Methamphetamine (Generic; Desoxyn®) Authorized Generic Concerta®) Methylphenidate ER Susp (Quillivant XR®) Methylphenidate IR (Ritalin®) Modafinil Tablet (Generic) Methylphenidate Solution (Generic; Authorized Generic; Methylin®) Methylphenidate -

Uveitis Therapy: the Corticosteroid Options

Drugs https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-020-01314-y REVIEW ARTICLE Uveitis Therapy: The Corticosteroid Options Lianna M. Valdes1 · Lucia Sobrin1 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 Abstract Uveitis is characterized by intraocular infammation involving the uveal tract; its etiologies generally fall into two broad categories: autoimmune/infammatory or infectious. Corticosteroids are a powerful and important class of medications ubiquitous in the treatment of uveitis. They may be given systemically or locally, in the form of topical drops, periocular injection, intravitreal suspension, or intravitreal implant. This review describes each of the currently available corticosteroid treatment options for uveitis, including favorable and unfavorable characteristics of each as well as applicable clinical trials. The main advantage of corticosteroids as a whole is their ability to quickly and efectively control infammation early on in the course of uveitis. However, they can have serious side efects, whether localized to the eye (such as cataract and elevated intraocular pressure) or systemic (such as osteonecrosis and adrenal insufciency) and in the majority of cases of uveitis are not an appropriate option for long-term therapy. Key Points Clinical features of uveitis include keratic precipitates, ante- rior chamber cell and fare, anterior and posterior synechiae, Corticosteroids are an important mainstay in the treat- iris nodules, snowballs, snowbanks, vitreous haze and cells, ment of uveitis. choroidal lesions, and choroidal thickening. Uncontrolled uveitis can be complicated by cystoid macular edema, retinal Corticosteroids can be given systemically or locally, in vasculitis, optic nerve head edema, and subretinal fuid. A the form of topical drops, periocular injection, intravit- mainstay of treatment for uveitis and its sequelae is the use real suspension, or intravitreal implant; each option has of corticosteroids. -

LOTEMAX®Loteprednol Etabonateophthalmic Suspension

LOTEMAX- loteprednol etabonate suspension/ drops Bausch & Lomb Incorporated ---------- LOTEMAX® loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5% STERILE OPHTHALMIC SUSPENSION Rx only DESCRIPTION LOTEMAX® (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension) contains a sterile, topical anti- inflammatory corticosteroid for ophthalmic use. Loteprednol etabonate is a white to off-white powder. Loteprednol etabonate is represented by the following structural formula: C24H31ClO7 Mol. Wt. 466.96 Chemical Name: chloromethyl 17α-[(ethoxycarbonyl)oxy]-11β-hydroxy-3-oxoandrosta-1,4-diene-17β-carboxylate Each mL contains ACTIVE: Loteprednol Etabonate 5 mg (0.5%); INACTIVES: Edetate Disodium, Glycerin, Povidone, Purified Water and Tyloxapol. Hydrochloric Acid and/or Sodium Hydroxide may be added to adjust the pH. The suspension is essentially isotonic with a tonicity of 250 to 310 mOsmol/kg. PRESERVATIVE ADDED: Benzalkonium Chloride 0.01%. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Corticosteroids inhibit the inflammatory response to a variety of inciting agents and probably delay or slow healing. They inhibit the edema, fibrin deposition, capillary dilation, leukocyte migration, capillary proliferation, fibroblast proliferation, deposition of collagen, and scar formation associated with inflammation. There is no generally accepted explanation for the mechanism of action of ocular corticosteroids. However, corticosteroids are thought to act by the induction of phospholipase A2 inhibitory proteins, collectively called lipocortins. It is postulated that these proteins control the biosynthesis of potent mediators of inflammation such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes by inhibiting the release of their common precursor arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is released from membrane phospholipids by phospholipase A2. Corticosteroids are capable of producing a rise in intraocular pressure (IOP). Loteprednol etabonate is structurally similar to other corticosteroids. However, the number 20 position ketone group is absent. -

Product-Specific Recommendations for Generic Drug Development

Guidances (Drugs) > Product-Specific Recommendations for Generic Drug Development U.S. Food and Drug Administration Home Drugs Guidance, Compliance & Regulatory Information Guidances (Drugs) Product-Specific Recommendations for Generic Drug Development SHARE TWEET LINKEDIN PIN IT EMAIL PRINT To successfully develop and manufacture a generic drug product, an applicant should consider that their product is expected to be: pharmaceutically equivalent to its reference listed drug (RLD), i.e., to have the same active ingredient, dosage form, strength, and route of administration under the same conditions of use, bioequivalent to the RLD, i.e., to show no significant difference in the rate and extent of absorption of the active pharmaceutical ingredient; and, consequently, therapeutically equivalent, i.e., to be substitutable for the RLD with the expectation that the generic product will have the same safety and efficacy as its reference listed drug. According 21 CFR 320.24, different types of evidence may be used to establish bioequivalence for pharmaceutically equivalent drug products, including in vivo or in vitro testing, or both. The selection of the method used to demonstrate bioequivalence depends upon the purpose of the study, the analytical methods available, and the nature of the drug product. Under this regulation, applicants must conduct bioequivalence testing using the most accurate, sensitive, and reproducible approach available among those set forth in 21 CFR 320.24. As the initial step for selecting methodology for generic drug product development, applicants are referred to the following draft guidance: Draft Guidance for Industry on Bioequivalence Studies With Pharmacokinetic Endpoints for Drugs Submitted Under an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) (Dec. -

WO 2015/168523 Al 5 November 2015 (05.11.2015) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2015/168523 Al 5 November 2015 (05.11.2015) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C07J 75/00 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/US20 15/028748 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 1 May 2015 (01 .05.2015) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (25) Filing Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 61/987,012 1 May 2014 (01.05.2014) (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicant: INTEGRAL BIOSYSTEMS LLC [US/US]; GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, 19A Crosby Drive, Suite 200, Bedford, Massachusetts TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, 01730 (US). -

WO 2007/061454 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (43) International Publication Date (10) International Publication Number 31 May 2007 (31.05.2007) PCT WO 2007/061454 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agents: DEL BUONO, BRIAN J. et al.; STERNE, C07D 403/12 (2006.01) KESSLER, GOLDSTEIN & FOX P.L.L.C, 1100 New York Avenue, N.w., Washington, District Of Columbia (21) International Application Number: 20005 (US). PCT/US2006/027435 (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, (22) International Filing Date: 14 July 2006 (14.07.2006) AT,AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, (25) Filing Language: English GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, (26) Publication Language: English LU, LV,LY,MA, MD, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, SY, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW 11/284,109 22 November 2005 (22.1 1.2005) US PCT/US2005/042362 (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 22 November 2005 (22. 11.2005) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): MED- ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, TM), POINTE HEALTHCARE INC. -

Lotemax (Loteprednol Etabonate) – Expanded Indication

Lotemax® (loteprednol etabonate) – Expanded indication • On July 20, 2018, the FDA announced the approval of Bausch and Lomb’s Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate) ophthalmic gel 0.5%, for the treatment of post-operative inflammation and pain following ocular surgery. — The expanded indication allows for pediatric use of Lotemax. — Previously, Lotemax was approved only in adult patients for the same indication. • Lotemax 0.5% is also available as an ophthalmic suspension and an ointment. — Lotemax suspension is indicated for certain steroid-responsive inflammatory conditions when the inherent hazard of steroid use is accepted to obtain an advisable diminution in edema and inflammation. — Lotemax ointment carries the same indication as Lotemax gel, but is only indicated in adults. • Loteprednol is also available as a branded ophthalmic 0.2% suspension (Alrex®) and a branded combination suspension (Zylet® [loteprednol 0.5%/tobramycin 0.3%]). — Alrex is indicated for the temporary relief of the signs and symptoms of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. — Zylet is indicated for steroid-responsive inflammatory ocular conditions for which a corticosteroid is indicated and where superficial bacterial ocular infection or a risk of bacterial ocular infection exists. • The expanded indication for Lotemax was based on a safety and efficacy study of 107 patients from birth to < 11 years of age undergoing cataract surgery. Patients were randomized to receive either Lotemax or prednisolone acetate ophthalmic suspension 1% four times daily for 14 days. — At day 14, the percentage of patients with complete clearing of anterior chamber inflammation was 57% in the Lotemax group vs. 63% in the prednisolone group. — In addition, pediatric use of Lotemax is also supported by evidence from adequate and well- controlled trials of Lotemax in adults.