Maud De Chaworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area

I Contrebis 2000 The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area. Phil Hudson Introduction This paper hopes to provide a chronological outline of the events which were important in creating the landscape changes in the Quernmore forest area. There was movement into the area by prehistoric man and some further incursions in the Anglo- Saxon and the Norse periods leading to Saxon estates and settled agricultural villages by the time of the Norman Conquest. These villages and estates were taken over by the Normans, and were held of the King, as recorded in Domesday. The Post-Nonnan conquest new lessees made some dramatic changes and later emparked, assarted and enclosed several areas of the forest. This resulted in small estates, farms and vaccaries being founded over the next four hundred years until these enclosed areas were sold off by the Crown putting them into private hands. Finally there was total enclosure of the remaining commons by the 1817 Award. The area around Lancaster and Quernmore appears to have been occupied by man for several thousand years, and there is evidence in the forest landscape of prehistoric and Romano-British occupation sites. These can be seen as relict features and have been mapped as part of my on-going study of the area. (see Maps 1 & 2). Some of this field evidence can be supported by archaeological excavation work, recorded sites and artif.act finds. For prehistoric occupation in the district random finds include: mesolithic flints,l polished stone itxe heads at Heysham;'worked flints at Galgate (SD 4827 5526), Catshaw and Haythomthwaite; stone axe and hammer heads found in Quernmore during the construction of the Thirlmere pipeline c1890;3 a Neolithic bowl, Mortlake type, found in Lancaster,o a Bronze Age boat burial,s at SD 5423 5735: similar date fragments of cinerary urn on Lancaster Moor,6 and several others discovered in Lancaster during building works c1840-1900.7 Several Romano-British sites have been mapped along with finds of rotary quems from the same period and associated artifacts. -

Philippa of Hainaut, Queen of England

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY VMS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/philippaofhainauOOwhit PHILIPPA OF HAINAUT, QUEEN OF ENGLAND BY LEILA OLIVE WHITE A. B. Rockford College, 1914. THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1915 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL ..%C+-7 ^ 19</ 1 HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ftlil^ &&L^-^ J^B^L^T 0^ S^t ]J-CuJl^^-0<-^A- tjL_^jui^~ 6~^~~ ENTITLED ^Pt^^L^fifi f BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF CL^t* *~ In Charge of Major Work H ead of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination CONTENTS Chapter I Philippa of Hainaut ---------------------- 1 Family and Birth Queen Isabella and Prince Edward at Valenciennes Marriage Arrangement -- Philippa in England The Wedding at York Coronation Philippa's Influence over Edward III -- Relations with the Papacy - - Her Popularity Hainauters in England. Chapter II Philippa and her Share in the Hundred Years' War ------- 15 English Alliances with Philippa's Relatives -- Emperor Louis -- Count of Hainaut Count of Juliers Vow of the Heron Philippa Goes to the Continent -- Stay at Antwerp -- Court at Louvain -- Philippa at Ghent Return to England Contest over the Hainaut Inherit- ance -- Battle of Neville's Cross -- Philippa at the Siege of Calais. Chapter III Philippa and her Court -------------------- 29 Brilliance of the English Court -- French Hostages King John of France Sir Engerraui de Coucy -- Dis- tinguished Visitors -- Foundation of the Round Table -- Amusements of the Court -- Tournaments -- Hunting The Black Death -- Extravagance of the Court -- Finan- cial Difficulties The Queen's Revenues -- Purveyance-- uiuc s Royal Manors « Philippa's Interest in the Clergy and in Religious Foundations — Hospital of St. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Family Tree Maker

Ancestors of Ulysses Simpson Grant Generation No. 1 1. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY. He was the son of 2. Jesse Root Grant and 3. Hannah Simpson. He married (1) Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. She was born 26 Jan 1826 in White Haven Plantation, St. Louis Co. MO, and died 14 Dec 1902 in Washington, D. C.. She was the daughter of "Colonel" Frederick Fayette Dent and Ellen Bray Wrenshall. Generation No. 2 2. Jesse Root Grant, born 23 Jan 1794 in Greensburg, Westmoreland Co., PA; died 29 Jan 1873 in Covington, Campbell Co., KY. He was the son of 4. Noah Grant III and 5. Rachel Kelley. He married 3. Hannah Simpson 24 Jun 1821 in The Simpson family home. 3. Hannah Simpson, born 23 Nov 1798 in Horsham, Philadelphia Co., PA; died 11 May 1883 in Jersey City, Coventry Co., NJ. She was the daughter of 6. John Simpson, Jr. and 7. Rebecca Weir. Children of Jesse Grant and Hannah Simpson are: 1 i. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY; married Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. ii. Samuel Simpson Grant iii. Orville Grant iv. Clara Grant v. Virginia "Nellie" Grant vi. Mary Frances Grant Generation No. 3 4. Noah Grant III, born 20 Jun 1748; died 14 Feb 1819 in Maysville, Mason Co., KY. He was the son of 8. -

The Eructavit Is Generally Linked with Marie of Champagne. I Should Like

淡江人文社會學刊【第十期】 The Eructavit is generally linked with Marie of Champagne. I should like to demonstrate, however, that this Old French metrical paraphrase of Psalm XLIV (in the Vulgate edition) is inextricably linked with Marie of Brabant as well. In pursuing this link, I believe I can explain both the occasion and the content of (Paris, BN) Arsenal 3142, the manuscript generally thought to have been composed for Marie of Brabant. Furthermore, in so doing, I should like to establish a possible dating, as well as an occasion, for the Eructavit and for the Arsenal Manuscript 3142. In order to do this, I should like to introduce the setting in which the Eructavit was written, the people surrounding its production, and the familial ties connecting the existing manuscripts of the Eructavit to the Arsenal Manuscript 3142. I should then like to deal with the form of the Arsenal Manuscript in terms of the Eructavit and the 44th Psalm. Marie of France, the eldest daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine and of Louis VII of France, was given in marriage in 1154 to Henry I, called the Liberal, of Champagne.(1) Henry of Champagne was a learned man, a recipient of sermons, commentaries on the Psalms, and liturgical pieces, including ten sequences (Benton, 1961, p. 556). John of Salisbury (who at the time of the Becket case was exiled from England and staying with his friend Pierre de Celle, then abbot of Saint-Remi-de Reims and friend as well of Henry) tells us of the “great pleasure which the Count Henry took in discussing literary subjects with learned men.”(2) Furthermore, Chretien de Troyes, Evrat, Gace Brule, Gautier d’Arras, and Simon Chevre d’Or, all known poets, acknowledge the personal intervention of Henry or Marie in their work.(3) The court of Champagne was well established as a center of learning and patronage. -

Report and Accounts Year Ended 31St March 2019

Report and Accounts Year ended 31st March 2019 Preserving the past, investing for the future LLancaster Castle’s John O’Gaunt gate. annual report to 31st March 2019 Annual Report Report and accounts of the Duchy of Lancaster for the year ended 31 March 2019 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall (Accounts) Act 1838. annual report to 31st March 2019 Introduction Introduction History The Duchy of Lancaster is a private In 1265, King Henry III gifted to his estate in England and Wales second son Edmund (younger owned by Her Majesty The Queen brother of the future Edward I) as Duke of Lancaster. It has been the baronial lands of Simon de the personal estate of the reigning Montfort. A year later, he added Monarch since 1399 and is held the estate of Robert Ferrers, Earl separately from all other Crown of Derby and then the ‘honor, possessions. county, town and castle of Lancaster’, giving Edmund the new This ancient inheritance began title of Earl of Lancaster. over 750 years ago. Historically, Her Majesty The Queen, Duke of its growth was achieved via In 1267, Edmund also received Lancaster. legacy, alliance and forfeiture. In from his father the manor of more modern times, growth and Newcastle-under-Lyme in diversification have been delivered Staffordshire, together with lands through active asset management. and estates in both Yorkshire and Lancashire. This substantial Today, the estate covers 18,481 inheritance was further enhanced hectares of rural land divided into by Edmund’s mother, Eleanor of five Surveys: Cheshire, Lancashire, Provence, who bestowed on him Staffordshire, Southern and the manor of the Savoy in 1284. -

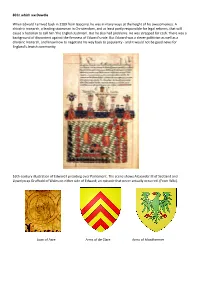

80 in Which We Dawdle When Edward I Arrived Back in 1289 from Gascony, He Was in Many Ways at the Height of His Awesomeness

80 In which we Dawdle When Edward I arrived back in 1289 from Gascony, he was in many ways at the height of his awesomeness. A chivalric monarch, a leading statesman in Christendom, and at least partly responsible for legal reforms, that will cause a historian to call him 'the English Justinian'. But he also had problems. He was strapped for cash. There was a background of discontent against the firmness of Edward's rule. But Edward was a clever politician as well as a chivalric monarch, and knew how to negotiate his way back to popularity - and it would not be good news for England's Jewish community. 16th-century illustration of Edward I presiding over Parliament. The scene shows Alexander III of Scotland and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales on either side of Edward; an episode that never actually occurred. (From Wiki). Joan of Acre Arms of de Clare Arms of Monthermer Northampton Charing Cross Geddington Plaque at Northampton Eleanor of Castile 81 The Great Cause Through a stunning piece of bad luck, Alexander III left no heirs. And now there was no clear successor to his throne of Scotland. For the search for the right successor, the Scottish Guardians of the Realm turned to Scotland's friend - England. But Edward had other plans - for him this was a great opportunity to revive the claims of the kings of England to be overlords of all Britain. The Maid of Norway Coronation Chair and Stone of Scone Stain Glass window Lerwick Town Hall King Edward's Chair today sans the Stone of Destiny. -

Open Finalthesis Weber Pdf.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES FRACTURED POLITICS: DIPLOMACY, MARRIAGE, AND THE LAST PHASE OF THE HUNDRED YEARS WAR ARIEL WEBER SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Medieval Studies with honors in Medieval Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Benjamin T. Hudson Professor of History and Medieval Studies Thesis Supervisor/Honors Adviser Robert Edwards Professor of English and Comparative Literature Thesis Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The beginning of the Hundred Years War came about from relentless conflict between France and England, with roots that can be traced the whole way to the 11th century, following the Norman invasion of England. These periods of engagement were the result of English nobles both living in and possessing land in northwest France. In their efforts to prevent further bloodshed, the monarchs began to engage in marriage diplomacy; by sending a young princess to a rival country, the hope would be that her native people would be unwilling to wage war on a royal family that carried their own blood. While this method temporarily succeeded, the tradition would create serious issues of inheritance, and the beginning of the last phase of the Hundred Years War, and the last act of success on the part of the English, the Treaty of Troyes, is the culmination of the efforts of the French kings of the early 14th century to pacify their English neighbors, cousins, and nephews. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Plantagenet Claim to France................................................................................... -

Notes on the Lancaster Estates in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

NOTES ON THE LANCASTER ESTATES IN THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES BY DOROTHEA OSCHINSKY, D.Phil., Ph.D. Read 24 April 1947 UR knowledge of mediaeval estate administration is O based mainly on sources which relate to ecclesiastical estates, because these are easier of access and, as a rule, more complete. The death of an abbot affected a monastic estate only in so far as his successor might be a better or a worse husbandman; the estate was never divided between heirs, was not diminished by the endowment of widows and daughters, and was not doubled by prudent marriages as were seignorial estates. Furthermore, the ecclesiastics had frequently been granted their lands in frankalmoin, and no rent or service was rendered in return. With few exceptions their manors lay near the centre of the estate; and, finally, the clerics had sufficient leisure to supervise their estates themselves and little difficulty in providing a staff trained to work the estates intensively and profitably. Therefore we realise that any conclusions which are based on ecclesiastical estates only must necessarily be one-sided, and that before we can draw a general picture of the estate administration in the Middle Ages, we have to work out the estate adminis tration on at least some of the more important seignorial estates. The Lancaster estates with their changing fate are well able to reveal the chief characteristics of a seignorial estate, its extent, management and administration. The vastness of the estates of the Earls of Lancaster, and the importance of the family in the political history of the country, accen tuated and multiplied the difficulties of the estate adminis tration. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

The Red Rose of Lancaster? JOHN ASHDOWN—HILL In the fifteenth century the rival houses of Lancaster and York fought the ‘Wars of the Roses’ for possession of the crown. When, in 1485, the new Tudor monarch, Henry VII, brought these wars to an end, he united, by his mam'age to Elizabeth of York, the red rose of Lancaster and the white rose of York, to create a new emblem and a new dynasty. Thus was born the Tudor rose. So might run a popular account, and botanists, searching through the lists of medieval rose cultivars, have even proposed identifications of the red rose of Lancaster with Rosa Gallica and the white rose of York with Rosa Alba, while the bi-coloured Tudor rose is linked to the naturally occurring variegated sport of Rosa Gallica known as ‘Rosa Mundi’ (Rosa Gallica versicolor), or alternatively, to the rather paler Rosa Damascena versicolor. It should, perhaps, be observed that Rosa Gallica, while somewhat variable in colour. is more likely to be a shade of pink than bright red, and Rosa Alba, while generally white in colour, also occurs in shades of pink, so that in nature the colour~distinction between the two roses is not always clear. ‘Rosa Mundi’ is also strictly speaking variegated in two shades of pink, rather than being literally red and white.‘ The label ‘Wars of the Roses’was a late invention, first employed only in 1829, by Sir Walter Scott, in his romantic novel Anne of Geierstein.2 The story of the rose emblems might appear on casual inspection to be well-founded, for we find ample evidence of Tudor roses bespattering Tudor coinage and royal architecture, for example, at Hampton Court, the Henry VII chapel at Westminster, and at Cambridge, on the gates of Christ’s and St John’s Colleges, and in King’s College chapel. -

El Impacto De Las Relaciones Familiares Y Conyugales En Los Reinados De Las Reinas Titulares De Navarra (1274-1517)

ANUARIO DE ESTUDIOS MEDIEVALES 46/1, enero-junio de 2016, pp. 167-201 ISSN 0066-5061 doi:10.3989/aem.2016.46.1.05 RULING & RELATIONSHIPS: THE FUNDAMENTAL BASIS OF THE EXERCISE OF POWER? THE IMPACT OF MARITAL & FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS ON THE REIGNS OF THE QUEENS REGNANT OF NAVARRE (1274-1517)1 PODER Y PARENTESCO: ¿LOS FUNDAMENTOS DE REINAR? EL IMPACTO DE LAS RELACIONES FAMILIARES Y CONYUGALES EN LOS REINADOS DE LAS REINAS TITULARES DE NAVARRA (1274-1517) ELENA WOODACRE University of Winchester Summary: Family relationships were the Resumen: Las relaciones familiares cons- foundation of dynastic monarchy and tituyeron el fundamento de la monarquía provided a crucial basis for the support dinástica y proporcionaron una base de of the rule of a reigning queen, who was apoyo crucial en el gobierno de una reina arguably in a far more vulnerable position con potestad propia, que se encontraba en than that of her male counterparts. This una posición mucho más vulnerable que article will examine the situation of the sus homólogos masculinos. Este artículo queens regnant of Navarre, between 1274 examinará la situación de las reinas titulares and 1517 with particular regard to their de Navarra entre 1274 y 1517, con especial relationship with their natal and marital énfasis en su relación con sus familias, tanto families. It will highlight various exam- de origen como política. Estudiaremos va- ples which demonstrate the key support rios ejemplos que ponen de manifi esto la that reigning queens received from their importancia de los apoyos que las reinas go- family members, which was especially bernadoras recibieron de los miembros de vital in times of crisis. -

Katherine Swynford : the Story of John of Gaunt and His Scandalous Duchess Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KATHERINE SWYNFORD : THE STORY OF JOHN OF GAUNT AND HIS SCANDALOUS DUCHESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alison Weir | 496 pages | 29 Jun 2011 | Vintage Publishing | 9780712641975 | English | London, United Kingdom Katherine Swynford : The Story of John of Gaunt and His Scandalous Duchess PDF Book Visitor Guest Admin. His status was high and he was in search of a fortune to match. There was much anger against the government, most of it directed at John of Gaunt, who was held responsible for England's poor prowess in the war and the crippling poll tax. Richard was an attractive child, with golden hair, blue eyes and pink cheeks, intelligent and well educated, and hopes were expressed that, as he grew to manhood, he would emulate his famous father. The king kneeled and was crouched down just in front of me. The late duke of York had been recognised as rightful king of England. In Hugh Chisholm. Already there was widespread discontent at the dismal way the war was going. He was an important figure in royal circles. Incidentally, Joan Beaufort, her daughter, chose to be buried in a monument next to her mother at Lincoln, rather than resting with either of her two husbands, Sir Robert Ferrers and Ralph Neville, the Earl of Westmorland, so for both women, an identity of their own outweighed conformity and eternal rest with their married families. Whereupon the Duke muttered, 'Rather than endure this, I should take him by the hair and drag him out of the church. The winner of Britain's prestigious Whitbread Prize and a bestseller there for months, this wonderfully readable biography offers a rich, rollicking picture of late-eighteenth-century British aristocr… More.