Out of Reach: Regressive Trends in Credit Card Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEO 312, Credit CARD Act: Interest Rate Increases and Rules on Unfair

Office of Thrift Supervision Montrice Godard Yakimov RESCINDEDDepartment of the Treasury Managing Director, Compliance and Consumer Protection 1700 G Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20552 • (202) 906-6173 July 13, 2009 MEMORANDUM FOR: CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICERS FROM: Montrice Godard Yakimov, Managing Director Compliance and Consumer Protection SUBJECT: Credit CARD Act: Interest Rate Increases and Rules on Unfair Practices On May 22, 2009, President Obama signed into law the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 (Credit CARD Act). In addition to providing a number of other important protections for consumers, the Credit CARD Act will address interest rate reductions on open end consumer credit plans. It will require institutions to: (1) Maintain reasonable methodologies for assessing the credit risk of the obligor, market conditions, or other factors upon which an annual percentage rate (APR) increase is based; (2) Not less frequently than once every six months, review accounts for which an APR has been increased since January 1, 2009 to assess whether such factors have changed, including whether any risk has declined (“Look Back” provision); (3) Reduce an APR previously increased when a reduction is indicated by the review; and (4) Provide written notice of the reasons when an increase is indicated by the review. These provisions do not become effective until August 2010. However, OTS strongly encourages institutions under its supervision to consider them now as preparations are made to comply with the Credit CARD Act, particularly with respect to the requirements of the Look Back provision. The Credit CARD Act also expands the prohibition against five practices that the OTS, the Federal Reserve Board (FRB), and the National Credit Union Administration recently found to be unfair under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which prohibits unfair or deceptive acts and practices. -

The Credit CARD Act of 2009: What Did Banks Do?

No. 13-7 The Credit CARD Act of 2009: What Did Banks Do? Vikram Jambulapati and Joanna Stavins Abstract The Credit CARD Act of 2009 was intended to prevent practices in the credit card industry that lawmakers viewed as deceptive and abusive. Among other changes, the Act restricted issuers’ account closure policies, eliminated certain fees, and made it more difficult for issuers to change terms on credit card plans. Critics of the Act argued that because of the long lag between approval and implementation of the law, issuing banks would be able to take preemptive actions that might disadvantage cardholders before the law could take effect. Using credit bureau data as well as individual data from a survey of U.S. consumers, we test whether banks closed consumers’ credit card accounts or otherwise restricted access to credit just before the enactment of the CARD Act. Because the period prior to the enactment of the CARD Act coincided with the financial crisis and recession, causality in this case is particularly difficult to establish. We find evidence that a higher fraction of credit card accounts were closed following the Federal Reserve Board’s adoption of its credit card rules. However, we do not find evidence that banks closed credit card accounts or deteriorated terms of credit card plans at a higher rate between the time when the CARD Act was signed and when its provisions became law. JEL Codes: D14, D18, G28 When this paper was written Vikram Jambulapati was a research assistant at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. He is now a Ph.D. -

Visa's Annual Report

Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 Mission Statement To connect the world through the most innovative, reliable and secure digital payment network that enables individuals, businesses and economies to thrive. Financial Highlights (GAAP) In millions (except for per share data) FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 Operating revenues $13,880 $15,082 $18,358 Operating expenses $4,816 $7,199 $6,214 Operating income $9,064 $7, 883 $12,144 Net income $6,328 $5,991 $6,699 Stockholders' equity $29,842 $32,912 $32,760 Diluted class A common stock earnings per share $2.58 $2.48 $2.80 Financial Highlights (ADJUSTED)1 In millions (except for per share data) FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 Operating revenues $13,880 $15,082 $18,358 Operating expenses $4,816 $5,060 $6,022 Operating income $9,064 $10,022 $12,336 Net income $6,438 $6,862 $8,335 Diluted class A common stock earnings per share $2.62 $2.84 $3.48 Operational Highlights² 12 months ended September 30 (except where noted) 2015 2016 2017 Total volume, including payments and cash volume³ $7.4 trillion $8.2 trillion $10.2 trillion Payments volume³ $4.9 trillion $5.8 trillion $7.3 trillion Transactions processed on Visa's networks 71.0 billion 83.2 billion 111.2 billion Cards⁴ 2.4 billion 2.5 billion 3.2 billion Stock Performance The accompanying graph and chart compares the cumulative total return on $350 Visa’s common stock with the cumulative total return on Standard & Poor’s 500 Index and the Standard & Poor’s 500 Data Processing Index from September 30, $300 2012 through September 30, 2016. -

GET the FACTS! Capital One’S Business Practices Raise Concerns About Its Corporate Governance

GET THE FACTS! Capital One’s Business Practices Raise Concerns about its Corporate Governance Decision-makers and advocates need to know the critical facts about Capital One and its corporate practices. Empire Building at its Best? In less than 5 years, Capital One is poised to triple its asset base. Total Assets (in millions) 300 292 200 198 170 150 151 166 100 89 0 2005 2007 2009 2011 (Projected) u Since Capital One became a banking institution in 2005, it has pursued an aggressive growth strategy that has been described by analysts as “empire building at its best.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition • 727 15th St, NW, Washington, DC 20005 • 202-628-8866 • http://www.ncrc.org 1 The Rejection of Diversification in Favor of a High-Risk, Monoline Strategy: 75 percent of Capital One’s income, and 66 percent of its revenue, comes from a single source: credit cards. 2010 Income Analysis: 2010 Revenue Analysis: -3% -10% 5% 9% 30% 75% 28% 66% Credit Cards Credit Cards Consumer Banking Consumer Banking Commercial Banking Commercial Banking Other Other u Diversification allows a bank to reduce risk by relying on varied products for income and revenue, shielding it from downturns. Capital One, however, rejects diversification in favor of a monoline strategy. This high-risk approach—and the institutions that embraced it— were at the heart of America’s last financial crisis. National Community Reinvestment Coalition • 727 15th St, NW, Washington, DC 20005 • 202-628-8866 • http://www.ncrc.org 2 Capital One’s Idea of Consumer Banking? Give the Public Subprime Auto-Loans. -

Concise Encyclopedia of the Great Recession, 2007-2010

THE CONCISE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE GREAT RECESSION 2007–2010 Jerry M. Rosenberg The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2010 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2010 by Jerry M. Rosenberg All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosenberg, Jerry Martin. The concise encyclopedia of the great recession 2007–2010 / Jerry M. Rosenberg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-7660-6 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7661-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7691-0 (ebook) 1. Financial crises—United States—History—21st century—Dictionaries. 2. Recessions—United States—History—21st century—Dictionaries. 3. Financial institutions—United States—History—21st century—Dictionaries. I. Title. HB3743.R67 2010 330.9'051103—dc22 2010004133 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Ellen Celebrating fifty years of love and adventure. She is my primary motivation. As a lifelong partner, Ellen keeps me spirited and vibrant. -

Creating a Consumer Financial Protection Agency: a Cornerstone of America’S New Economic Foundation

S. HRG. 111–274 CREATING A CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION AGENCY: A CORNERSTONE OF AMERICA’S NEW ECONOMIC FOUNDATION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON THE CREATION OF A CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION AGENCY TO BE THE CORNERSTONE OF AMERICA’S NEW ECONOMIC FOUNDATION JULY 14, 2009 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Available at: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate/senate05sh.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 54–789 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut, Chairman TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama JACK REED, Rhode Island ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JIM BUNNING, Kentucky EVAN BAYH, Indiana MIKE CRAPO, Idaho ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey MEL MARTINEZ, Florida DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii BOB CORKER, Tennessee SHERROD BROWN, Ohio JIM DEMINT, South Carolina JON TESTER, Montana DAVID VITTER, Louisiana HERB KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE JOHANNS, Nebraska MARK R. WARNER, Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado EDWARD SILVERMAN, Staff Director WILLIAM D. DUHNKE, Republican Staff Director AMY S. FRIEND, Chief Counsel JONATHAN N. MILLER, Professional Staff Member KARA STEIN, Legislative Assistant RANDALL FASNACHT, GAO Detailee MARK OESTERLE, Republican Chief Counsel ANDREW J. OLMEM, JR., Republican Counsel DAWN RATLIFF, Chief Clerk DEVIN HARTLEY, Hearing Clerk SHELVIN SIMMONS, IT Director JIM CROWELL, Editor (II) CONTENTS TUESDAY, JULY 14, 2009 Page Opening statement of Chairman Dodd ................................................................. -

Making Prepaid Safe for Consumers: a Framework for Providing Deposit Insurance and Regulation E Protections

ARTICLE 5 (WILSON).DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 6/16/15 11:51 AM MAKING PREPAID SAFE FOR CONSUMERS: A FRAMEWORK FOR PROVIDING DEPOSIT INSURANCE AND REGULATION E PROTECTIONS Catherine Lee Wilson* General purpose reloadable prepaid cards are part of a larger trend to- ward a cashless society. This market offers significant benefits to both tra- ditional depository institutions and new non-bank entrants in the payments industry. Electronic transfers significantly reduce the costs associated with paper-based payment systems. To balance the benefits received by pay- ment providers, consumer protections must be established to prevent con- sumers from becoming the sole bearers of the risks inherent in any payment system. Simple protections, those traditionally afforded to mainstream banking clients using checking accounts and debit cards, must be adopted for the GPR prepaid product to ensure long-term product safety for con- sumers. GPR prepaid cards are a new product, so deposit insurance should simply be extended to maintain the historical principles underlying deposit insurance. Likewise, the extension of Regulation E protections to GPR prepaid cards would simply complete work initiated by the Federal Reserve eighteen years ago. Both the EFTA and Dodd-Frank give the CFPB the au- thority to extend these consumer protections. Part I of this Article will provide a brief overview of the prepaid card industry and consumer use of the GPR prepaid product. In Part II, the Article outlines the gaps in the regulatory scheme for prepaid cards and highlights the initial steps federal regulators have taken to close the gaps. Part III outlines reasons for ex- tending consumer protections to GPR prepaid cards by illustrating that con- sumers are unable to protect against risks inherent in GPR prepaid card programs. -

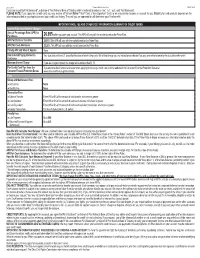

How We Will Calculate Your Balance:We Use a Method Called “Average Daily Balance (Including New Purchases)”. Index and When

232 - 121144 Platinum Edition® Visa® Card T-GULF-2005 Cards are issued by First Bankcard®, a division of First National Bank of Omaha, which is referred to below as “we”, “us”, “our”, and “First Bankcard”. PLEASE NOTE: If you apply for a credit card, you may receive a Platinum Edition® Visa® Card, a Visa Signature® Card, or we may decline to open an account for you. Eligibility for card products depends on the information provided in your application and your credit card history. The card you are approved for will determine your Visa benefits. IMPORTANT RATE, FEE AND OTHER COST INFORMATION (SUMMARY OF CREDIT TERMS) Interest Rates and Interest Charges Annual Percentage Rate (APR) for Purchases 26.99% when you open your account. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Balance Transfers 26.99% This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Cash Advances 25.24%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. Penalty APR and When it Applies None How to Avoid Paying Interest on Your due date is at least 21 days after the close of each billing cycle. We will not charge you any interest on purchases if you pay your entire balance by the due date each month.1 Purchases Minimum Interest Charge If you are charged interest, the charge will be no less than $1.75. For Credit Card Tips from the To learn more about factors to consider when applying for or using a credit card, visit the website of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau at Consumer Financial Protection Bureau www.consumerfinance.gov/learnmore. -

Global Payments 2020-30 a Quantium Shift in the Next Decade Australia's Challenge

McLean Roche Consulting Group Global Payments 2020-30 A quantium shift in the next decade Australia’s challenge – to keep up 1 Submission To RBA Payments Boards – Future of Payments – January 2020 McLean Roche Consulting Group AUSTRALIA’S PAYMENT CHALLENGE Australian payments will see more change in the next 10 years than the last 40 years combined. Australia has an expensive US/Anglo legacy based retail payments system which will be challenge by new technology, new data uses, new players and the need to protect consumer rights and data. Consumer retail payments total $975.7 billion in 2019 and will reach $3.2 trillion by 2030. A faster rate of expansion will occur in SME and Corporate payments. Payments are a very high volume, low margin business with even the smallest changes in revenues or margins delivering significant changes in actual dollars. Regulators around the globe will be challenged by forces of change and this requires all regulators and politicians to be aware of the scale of change and ensure the regulatory frame work changes and evolves quickly. 4 MYTHS DOMINATE THE NARRATIVE 1. CASH WILL DISAPPEAR – many including regulators keep predicting the death of cash. While bank notes may disappear, various forms of cash now dominate retail payments in Australia combining to total 71% share. 2. CREDIT CARDS DOMINATE LENDING – consumer credit cards are in decline having peaked 8 years ago. All the leading indicators are falling – average balance, average spend, revolve rate and number of cards. Corporate and Commercial cards are the only growth story. 3. DIGITAL PAYMENTS ARE THE FUTURE – many payment products use the ‘digital’ tag for marketing ‘glint’ however the reality is all payment products using Visa, MasterCard, Amex or eftpos payment networks are not digital. -

Consumer Experiences with Credit Cards

December 2013 Vol. 99, No. 5 Consumer Experiences with Credit Cards Glenn B. Canner and Gregory Elliehausen, of the Division of Research and Statistics, prepared this article. Shira E. Stolarsky and Madura Watanagase provided research assistance. By offering consumers both a means to pay for goods and services and a source of credit to finance such purchases, credit cards have become the most widely used credit instrument in the United States. As a payment device, credit cards are a ready substitute for checks, cash, and debit cards for most types of purchases. Credit cards facilitate transactions that would otherwise be difficult or costly, such as purchases over the Internet, by telephone, or out- side the country. As a source of unsecured credit, credit cards provide consumers the option to finance at their discretion the purchase of an item over time without having to provide the creditor some form of collateral such as real estate or a vehicle. Moreover, the small required minimum payments on credit card balances allow consumers to determine themselves how quickly they want to repay the borrowed funds. Credit cards have other benefits as well, such as security protections on card transactions and rewards for use. All of these features have been valuable to consumers and have helped promote the widespread holding and use of credit cards. Recent fluctuations in economic activity and changes in the regulation of credit cards have greatly affected the credit card market. As a consequence of the Great Recession and the slow economic recovery that has ensued, many consumers have experienced difficult financial cir- cumstances.1 During much of this period large numbers of consumers fell behind on their credit card payments, causing delinquency and charge-off rates to rise sharply. -

Congressional Record—House H11257

October 13, 2009 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H11257 DAVID R. OBEY, which have not been any part of a pat- As a cosponsor of this important DAVID E. PRICE, tern of abuse of credit cards, were inad- change which will simply ensure that JOSE´ E. SERRANO, vertently swept into this. the 21-day requirement only applies to CIRO D. RODRIGUEZ, The gentleman from Vermont (Mr. credit card accounts, I urge immediate C. A. DUTCH WELCH) and the gentleman from Mis- passage of H.R. 3606. RUPPERSBERGER, souri (Mr. SKELTON) called this to the I reserve the balance of my time. ALAN B. MOLLOHAN, NITA M. LOWEY, attention of the committee, as did the Mr. FRANK of Massachusetts. I yield LUCILLE ROYBAL-ALLARD, National Credit Union Administration 4 minutes to the gentleman from SAM FARR, and the Credit Union National Associa- Vermont, the lead author of this bill, STEVEN R. ROTHMAN, tion; the latter, of course, being the Mr. WELCH. Managers on the Part of the House. private association of credit unions, Mr. WELCH. I thank the gentleman from Massachusetts (Mr. FRANK) and ROBERT C. BYRD, the former being the administrative DANIEL K. INOUYE, agency. They asked us to fix it. They my colleague. I thank the gentleman PATRICK J. LEAHY were quite correct. from New York (Mr. LEE) and Mr. (with a reservation Credit unions are a very important SKELTON. on the EB–5 agree- part of the structure of this country You know, Mr. Speaker, one of the ment), and it serves our consumers. And so things the American people have a BARBARA A. -

In Re Sam Callas; Michael K. Desmond, Not Individually but As Chapter 7

United States Bankruptcy Court Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division Transmittal Sheet for Opinions for Publishing and Posting on Website Will this opinion be published? Yes Bankruptcy Caption: Sam Callas Adversary Caption: Michael K. Desmond, not individually but as chapter 7 trustee for the bankruptcy estate of Sam Callas, v. American Express Centurion Bank, Inc. Bankruptcy No. 13 B 43900 Adversary No. 15 A 00140 Date of Issuance: September 27, 2016 Judge: Janet S. Baer Appearances of Counsel: Attorney for Plaintiff: Michael K. Desmond Figliulo & Silverman PC 10 South LaSalle Street, Suite 3600 Chicago, IL 60603 Attorney for Plaintiff: David L. Freidberg Law Office of David L. Freidberg, PC 1954 First Street, Suite 164 Highland Park, IL 60035 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION IN RE: ) Bankruptcy Case No. 13 B 43900 ) SAM CALLAS, ) Chapter 7 ) Debtor. ) Honorable Janet S. Baer ___________________________________ ) ) MICHAEL K. DESMOND, not individually ) but as chapter 7 trustee for the bankruptcy ) estate of SAM CALLAS, ) Adversary Case No. 15 A 00140 ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) AMERICAN EXPRESS CENTURION ) BANK, INC., ) ) Defendant. ) ___________________________________ ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Michael K. Desmond (the “Trustee”), as chapter 7 trustee for the bankruptcy estate of Sam Callas (the “Debtor”), filed a six-count adversary complaint against American Express Centurion Bank, Inc. (“American Express”), seeking to avoid and recover from American Express allegedly preferential or fraudulent transfers made by Katina Callas, the Debtor’s non- filing spouse (“Katina”), to American Express pursuant to 11 U.S.C. §§ 547(b), 548(a)(1), and 550(a) of the Bankruptcy Code.1 The Trustee also seeks disallowance of American Express’s claims against the bankruptcy estate under §§ 502(d) and (j) until American Express pays to the 1 Unless otherwise noted, all statutory and rule references are to the Bankruptcy Code, 11 U.S.C.