Deschooling Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s}". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man. -

Teaching in the University

Educational Foundations,David Hursh Summer 2003 Imagining the Future: Growing Up Working Class; Teaching in the University By David Hursh I never wanted to be a teacher. In school I constantly counted the minutes until the last bell, when I would be free to join the other boys playing whichever sport the season demanded. I measured my success not by test grades but by touchdowns and runs scored. Therefore, I am surprised that for the last thirty years I have been teaching. But it is in teaching, in the crucible of the classroom, that one can engage in asking ques- tions and making sense of one another and the world. It is in the classroom in which a gaggle of five and six year olds responded to my question of how the Grand Can- yon was formed with the unexpected but understand- able explanation of earthquakes and tornadoes. And it is in last night’s classroom of doctoral students — mostly teachers and administrators — in which we David Hursh is an associate professor deliberated over the effect that the current testing move- in the Warner Graduate School of ment has on our ability to engage students in making Education and Human Development sense of ourselves and the world. at the University of Rochester, How then did I move from being a working-class Rochester, New York. boy who experienced school as a digression from my 55 Imagining the Future real interest — sports — to someone who had made education his life work? In this paper I will describe my own understanding of the process. -

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H

Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth Anarchist Pedagogies: Collective Actions, Theories, and Critical Reflections on Education Edited by Robert H. Haworth © 2012 PM Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978–1–60486–484–7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011927981 Cover: John Yates / www.stealworks.com Interior design by briandesign 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com contents Introduction 1 Robert H. Haworth Section I Anarchism & Education: Learning from Historical Experimentations Dialogue 1 (On a desert island, between friends) 12 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 1 Anarchism, the State, and the Role of Education 14 Justin Mueller chapteR 2 Updating the Anarchist Forecast for Social Justice in Our Compulsory Schools 32 David Gabbard ChapteR 3 Educate, Organize, Emancipate: The Work People’s College and The Industrial Workers of the World 47 Saku Pinta cHAPteR 4 From Deschooling to Unschooling: Rethinking Anarchopedagogy after Ivan Illich 69 Joseph Todd Section II Anarchist Pedagogies in the “Here and Now” Dialogue 2 (In a crowded place, between strangers) 88 Alejandro de Acosta cHAPteR 5 Street Medicine, Anarchism, and Ciencia Popular 90 Matthew Weinstein cHAPteR 6 Anarchist Pedagogy in Action: Paideia, Escuela Libre 107 Isabelle Fremeaux and John Jordan cHAPteR 7 Spaces of Learning: The Anarchist Free Skool 124 Jeffery Shantz cHAPteR 8 The Nottingham Free School: Notes Toward a Systemization of Praxis 145 Sara C. -

GESTALT RECONSIDERED Titles from Gicpress ORGA:'-IIZATIONAL CONSULTING: a GFSTALT APPROACH Edwin C

GESTALT RECONSIDERED Titles From GICPress ORGA:'-IIZATIONAL CONSULTING: A GFSTALT APPROACH Edwin C. Nevts GFSTALT RECONSIDERED: A NEW APPROACH TO CONTAcr AND RFSISTANCE Cordon Wheeler THE NEUROTIC BEHAVIOR OF ORGANIZATIONS Uri Merry and George /. Brown GFSTALT THERAPY: PERSPECTIVFS AND APPLICATIONS Edwin C. Nevis THE COLLECTIVE SILENCE: GERMAN IDENTITY AND THE LEGACY OF SHAME Barbara Heimannsberg and Christopher J. Schmidt COMMUNITY AND CONFLUENCE: UNDOING THE CLINCH OF OPPRESSION Philip Licluenberg BECOMING A STEPF AMIL Y Patricia Papemow ON INTIMATE GROUND: A GFSTALT APPROACH TO WORKING WITH COUPLFS Cordon Wheeler and Stephanie Backman BODY PROCFSS: WORKING WITH THE BODY IN PSYCHOTHERAPY James I. Kepner HERE, NOW, NEXT: PAUL GOODMAN AND THE ORIGINS OF GFSTALT THERAPY Taylor Stoehr CRAZY HOPE & FINITE EXPERIENCE Paul Goodman and Taylor Stoehr IN SEARCH OF GOOD FORM: GFST ALT THERAPY WITH COUPLFS AND FAMILIFS Joseph C. Zinker THE VOICE OF SHAME: SILENCE AND CONNECTION IN PSYCHOTHERAPY Robert G. Lee and Gordon Wheeler HEALING TASKS: PSYCHOTHERAPY WITH ADULT SURIVIVORS OF CHILDHOOD ABUSE Jame, I. Kepner ADOL£SCENCE: PSYCHOTHERAPY AND THE EMERGENT SELF Mark McConville GEIlING BEYOND SOBRIETY: CLINICAL APPROACHFS TO LONG- TERMJlECOVERY Michael Craig Clemmens INTENTIONAL REVOLUTIONS: A SEVEN- POINT STRATEGY FOR TRANSFORMING ORGANIZATIONS Edwin C. Nevis, Joan Lancourt and Helen G. Vassallo IN SEARCH OF SELF: BEYOND INDIVIDUALISM IN WORKING WITH PEOPLE Cordon Wheeler THE HEART OF DEVELOPMENT: GFSTALT APPROACHFS TO WORKING WITH CillLDREN. AOOLfSCENTS. AND THEIR WORLDS ( 2 Volumes) Mark McConville and Gordon Wheeler BACK TO THE BEANSTALK: ENCHANTMENT & REALITY FOR COUPLFS Judith R. Brown THE DREAMER AND THE DREAM: ESSAYS AND REFLECTIONS ON GFSTALT THERAPY Raineue Eden Fantz and Arthur Roberts GFSTALT THERAPY-A NEW PARADIGM: FSSA YS IN GFSTALT THEORY AND MErHOD Sylvia Flemming Crocker THE lJr'.'FOLDING SELF Jean-Marie Rabine GESTALT RECONSIDERED A New Approach to Contact and Resistance GORDON WHEELER, Ph. -

Positioning Gestalt Professional Education in the Changing Cultural Context: the Experiences of Providers

Positioning Gestalt Professional Education in the Changing Cultural Context: The Experiences of Providers Author O'Regan, Patrick Published 2021-03-04 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School Educ & Professional St DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/4158 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/403242 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au POSITIONING GESTALT PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION IN THE CHANGING CULTURAL CONTEXT: THE EXPERIENCES OF PROVIDERS Patrick (Paddy) O’Regan Bachelor of Social Work, Master of Social Policy, Master of Gestalt Therapy School of Education and Professional Studies Arts, Education and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2020 Patrick O’Regan -November 2020 Positioning Gestalt Professional Education ABSTRACT Gestalt therapy is a form of psychotherapy founded in the early 1950s as an approach to enhancing the health of its clients within a supportive therapeutic relationship by enhancing their self-awareness, choice, and spontaneity. The provision of Gestalt professional education for Gestalt therapy practitioners is closely linked with the beginnings of Gestalt therapy. It mainly occurs in private training institutes. Gestalt professional education providers are under pressure to respond to the demands of a changing cultural context such as through the provision of credentials endorsed by national regulatory authorities. However, only limited empirical research has been conducted on that situation. The goal of this research project, then, was to explore the key understandings, dilemmas, experiences, and decisions of major players within Gestalt professional education institutes in relation to what they saw as the demands of the contemporary cultural context. -

Examining a Sample of the American-Mexican Scientific Cooperation in the 1960S: a Social Network Analysis of the CIDOC-Network

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Examining a Sample of the American-Mexican Scientific Cooperation in the 1960s: A Social Network Analysis of the CIDOC-Network Verfasserin Mag.phil. Elisabeth Lemmerer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 312 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Geschichte Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Martina Kaller-Dietrich ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have some particular debts I wish to acknowledge here. This work could never have happened if it were not for certain people who supported me along the way. • My family, in particular my parents • the supervisor of my final thesis, Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Martina Kaller-Dietrich • the University of Vienna, for granting the “Förderungsstipendium” for five weeks research in New York and Washington DC in winter 2008 • FAS.research and in particular Mr. Mag. Christian Gulas who helped me evaluate and display the SNA Charts • at Fordham University Rose Hill Campus Bronx, NY, Ms. Patrice Kane, Head of Archives and Special Collections, and Ms. Vivian Shen, Preservation and Conservation Librarian • in the Library of Congress, Washington DC, all obliging helpers and archivists, especially Mr. Thomas Mann, PhD 2 C O N T E N T Epistemological Interest 5 Methodology 8 State of Art 13 Presentation of the Social Network Analysis Charts 14 - SNA Chart No. 1: Quantity of Scientific Cooperation 15 - SNA Chart No. 2: Mutual Acquaintances 16 1 MAIN CIRCLE OF ILLICH’S COLLEAGUES AT CIDOC 17 1.1 Key Personality Everett W. Reimer 18 1.1.1 Portrait of Everett W. Reimer (1910-1998) 18 1.1.2 Reimer – Illich: In Search of Educational Alternatives 18 1.1.3 Reimer’s twelve ties within CIDOC: Berger, Borremans, Fitzpatrick, Freire, Holt, Julião, Ladner, Maccoby, McKnight, Robert, Sullivan, von Hentig 20 1.2 Key Personality Joseph Fitzpatrick 22 1.2.1 Portrait of Joseph P. -

Paul Goodman and the Origins of Gestalt Therapy

•I• •~ • A Gestalt Institute of Cleveland publication HERE NOW NEXT Here Now Next Paul Goodman and the Origins of Gestalt Therapy Taylor Stoehr Jossey,Bass Publishers • San Francisco Copyright© 1994 by Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, California 94104. Copyright under International, Pan American, and Universal Copyright Conventions. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form---except for brief quotation (not to exceed 1,000 words) in a review or professional work-without permission in writing from the publishers. e A Gestalt Institute of Cleveland publication Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Jossey-Bass books are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department at Jossey Bass Inc., Publishers. (415) 433-1740; Fax (415) 433-0499. For international orders, please contact your local Paramount Publishing International office. Manufactured in the United States of America. Nearly all Jossey-Bass books and jackets are printed on recycled paper containing at least 10 percent postconsumer waste, and many are printed with either soy- or vegetable-based ink, which emits fewer volatile organic compounds during the printing pro cess than petroleum-based ink. Selected quotations from Gestalt Therapy by Frederick Perls, M.D., Ralph F. Hefferline, Ph.D., and Paul Goodman, Ph.D., copyright © 1951, 1979 by Frederick Perls, Ralph F. Hefferline, and Paul Goodman, are reprinted by permission from Crown Publishers, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stoehr, Taylor, date. Here now next : Paul Goodman and the origins of Gestalt therapy / Taylor Stoehr. -

PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z

The following text was originally published in Prospects : the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO : International Bureau of Education), vol . XXIII, no . 3/4, June 1994, p. 575-95. ©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 1999 This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source. PAUL GOODMAN (1911-1972) Edgar Z. Friedenberg1 Paul Goodman died of a heart attack on 2 August 1972, a month short of his 61st birthday. This was not wholly unwise. He would have loathed what his country made of the 1970s and 1980s, even more than he would have enjoyed denouncing its crassness and hypocrisy. The attrition of his influence and reputation during the ensuing years would have been difficult for a figure who had longed for the recognition that had eluded him for many years, despite an extensive and varied list of publications, until Growing up absurd was published in 1960, which finally yielded him a decade of deserved renown. It is unlikely that anything he might have published during the Reagan-Bush era could have saved him from obscurity, and from the distressing conviction that this obscurity would be permanent. Those years would not have been kind to Goodman, although he was not too kind himself. He might have been and often was forgiven for this; as well as for arrogance, rudeness and a persistent, assertive homosexuality—a matter which he discusses with some pride in his 1966 memoir, Five years, which occasionally got him fired from teaching jobs. However, there was one aspect of his writing that the past two decades could not have tolerated. -

A Deseducação Obrigatória, Por Paul Goodman

A deseduccação obrigatória, por Paulo Goodman A DESEDUCAÇÃO OBRIGATÓRIA, POR PAUL GOODMAN LA DESEDUCACIÓN OBLIGATORIA, POR PAUL GOODMAN COMPULSORY MISEDUCATION, BY PAUL GOODMAN Ivan FORTUNATO1 Carolina Rodrigues CUNHA2 RESUMO: Este artigo, escrito na forma de ensaio, busca recuperar elementos que ajudam a refletir o modo massificador sobre o qual tende a operar a educação escolar. Especificamente, assenta-se sobre as ideias de um livro norte-americano, publicado por Paul Goodman na década de 1960, chamado “deseducação obrigatória”. Acredita-se que as críticas trazidas pelo autor, há mais de cinquenta anos, ainda são válidas e merecem ser discutidas no contexto escolar atual. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Deseducação. Educação formal. Escola. RESUMEN: Este artículo, escrito en forma de ensayo, busca recuperar elementos que ayudan a reflejar el modo masivo sobre el cual tiende a operar la educación escolar. Específicamente, se asienta sobre las ideas de un libro norteamericano, publicado por Paul Goodman en la década de 1960, llamado “deseducación obligatoria”. Se cree que las críticas traídas por el autor, hace más de cincuenta años, todavía son válidas y merecen ser discutidas en el contexto escolar actual. PALABRAS CLAVE: Deseducación. Educación formal. Escuela. ABSTRACT: This paper, written as an essay, seeks to recover elements that help to reflect the massification on which tends to operate the school education system. Specifically, it rests on the ideas of an American book, published by Paul Goodman in the 1960s, called "compulsory miseducation". It is believed that the criticisms brought by the author, over fifty years ago, are still valid and deserve to be discussed in the current school context. -

PAUL GOODMAN CHANGED MY LIFE a Film by Jonathan Lee

PAUL GOODMAN CHANGED MY LIFE a film by Jonathan Lee Booking Contact: Clemence Taillandier, Zeitgeist Films 201-736-0261 • [email protected] Marketing Contacts: Nancy Gerstman & Emily Russo, Zeitgeist Films 212-274-1989 • [email protected] • [email protected] A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE PAUL GOODMAN CHANGED MY LIFE A Film by Jonathan Lee Paul Goodman was once so ubiquitous in the American zeitgeist that he merited a “cameo” in Woody Allenʼs Annie Hall. Author of legendary bestseller Growing Up Absurd (1960), Goodman was also a poet, 1940s out queer (and family man), pacifist, visionary, co-founder of Gestalt therapy—and a moral compass for many in the burgeoning counterculture of the ʼ60s. Paul Goodman Changed My Life immerses you in an era of high intellect (that heady, cocktail-glass juncture that Mad Men has so effectively exploited) when New York was peaking culturally and artistically; when ideas, and the people who propounded them, seemed to punch in at a higher weight class than they do now. Using a treasure trove of archival multimedia—selections from Goodmanʼs poetry (read by Garrison Keillor and Edmund White); quotes from Susan Sontag, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Noam Chomsky; plentiful footage of Goodman himself; plus interviews with his family, peers and activists—director/producer Jonathan Lee and producer/editor Kimberly Reed (Prodigal Sons) have woven together a rich portrait of an intellectual heavyweight whose ideas are long overdue for rediscovery. PAUL GOODMAN BIO Born in New York City in 1911, Paul Goodman labored in obscurity as a writer and freelance intellectual until 1960 when the publication of Growing Up Absurd made him famous and a significant moral force of the decade. -

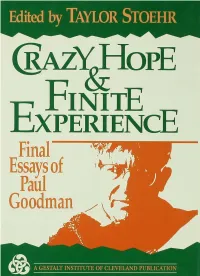

CRAZY HOPE and FINITE EXPERIENCE Crazy Hope and Finite Experience

..• A Gestalt Institute of Cleveland publication CRAZY HOPE AND FINITE EXPERIENCE Crazy Hope and Finite Experience Final Essays of Paul Goodman Taylor Stoehr, editor Jossey,Bass Inc. • San Francisco Copyright© 1994 by jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, California 94104. Copyright under International, Pan American, and Universal Copyright Conventions. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form-except for brief quotation (not to exceed 1,000 words) in a review or professional work-without permission in writing from the publishers. e A Gestalt Institute of Cleveland publication Substantial discounts on bulk quantities ofjossey-Bass books are available to corporations, professional associations, and other organizations. For details and discount information, contact the special sales department at jossey·Bass Inc., Publishers. (415) 433-1740; Fax (415) 433-0499. For international orders, please contact your local Paramount Publishing International office. Manufactured in the United States of America. Nearly all jossey-Bass books and jackets are printed on recycled paper that contains at least 50 percent recycled waste, including 10 percent postconsumer waste. Many of our materials are also printed with either soy· or vegetable· based ink; during the printing process these inks emit fewer volatile organic compounds (VOCs) than petroleum-based inks. VOCs contrib· ute to the formation of smog. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goodman, Paul, 1911-1972. Crazy hope and finite experience : final essays of Paul Goodman / [edited by) Taylor Stoehr.- 1st ed. p. em.- (Jossey-Bass social and behavioral science series) ISBN Q. 7879-0016-8 I. Stoehr, Taylor, date.